05. Jun 2014 - DOI 10.25626/0025

Prof. Dr. Ulrich Borsdorf has published numerous books and articles on the social history of industrialization, the regional history of the Ruhr region, photography and museology, and he has lectured at the universities of Bochum and Essen. As its first Director, he developed the concept for the new Ruhr Museum at Zollverein in Essen. He has curated numerous exhibitions there and elsewhere and now works as a museum consultant both in Germany and internationally.

The identity of the Ruhr area was shaped by industrialisation, which transformed the former rural landscape and small towns into a centre of the industrial revolution on the continent. However, the history of civilization in the Ruhr stretches back to the early middle ages. Two hundred years of industry left significant traces on nature, the landscape, and the mentalities and memories of human beings. All this is examined at the Ruhr Museum Essen, including the preconditions for and the serious consequences of industrialisation in the realm of nature, as well as the long and largely unknown history of the Ruhr area before industrial times.

The Ruhr area was once the largest and densest heavy industry region in Europe. At the peak of its development from 1910 to 1950, more than 200 pits extracted coal and several dozen blast furnace plants produced steel. Today, only three mines are left, with the last one due to close in 2018. The number of steel works has decreased to a mere handful. From 6.5 million, the population has shrunk to 5.3 million with a continuing downward trend. This immense structural change began at the end of the 1950s and is not yet finished.

The problems were - and still are - unemployment, the lack of appropriate qualifications, growth of the elderly population, growth of the young population with a migrant background, lower than average incomes, shrinking city budgets, vast deindustrialized zones, and a huge amount of now dysfunctional buildings and machines. The Ruhr has been fighting hard to recover. Since the 1970s the federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia (population: 18 million) has launched different recovery programmes, aided by the German government and the EU.

The Ruhr area is neither a natural landscape, nor is it a political or administrative unit. It consists of 53 cities which act more or less independently of each other. Since 1920 they have been members of a fairly loose administrative union, which has limited regional planning rights. The identity of the Ruhr area was shaped by industrialization, which transformed the former rural landscape and small towns into a centre of the industrial revolution on the continent. However, the history of civilization in the Ruhr stretches back to the early middle ages. Two hundred years of industry left significant traces on nature, the landscape, and the mentalities and memories of human beings. All this is examined at the Ruhr Museum Essen, including the preconditions for and the serious consequences of industrialisation in the realm of nature, as well as the long and largely unknown history of the Ruhr area before industrial times. Zollverein has become an icon of the Ruhr's industrial heritage, and, to some extent, an icon of German industry as a whole, at least Germany's heavy industry based on coal and steel. From the 1970s onwards, the idea of not destroying all of the industrial remains, but rather preserving at least some of the most important ones, and redeveloping them (as monuments, as sites of cultural activity and new business) has gained increasing public support. But this has not been a story of continuous success. There have been many struggles and it took the repeated efforts of an active civil society to achieve the present results.

It was only when it became clear that the industrial heritage could contribute to the economic recovery of the region and boost its people's morale that decisions were taken and public budgets were made available to redevelop some of the Ruhr's outstanding objects of the industrial past. Today, Zollverein is the very heart of that industrial heritage landscape and is a unique selling point for a small but beautiful new branch of the regional economy: industrial culture tourism.

The history of Zollverein began with the industrialist Franz Haniel, who in 1847 purchased some coalfields north of Essen in the immediate vicinity of a railway line that ran through West Prussia. Haniel named these coalfields Zollverein after the German Customs Union. This was a free trade area with standardized systems of measurement, one currency and no internal tariffs. It had come into force in 1834 following an agreement by 14 German states and promised an upswing and economic growth - Prometheus was unbound. The political situation following World War I and the economic crisis in the 1920s demanded innovative business plans in order to achieve profits. To better hold their own in international competition, in 1926 a large number of coal and steel works merged to found Vereinigte Stahlwerke AG, the largest steel group in Europe and the second largest in the world. Zollverein was assigned to it.

This huge coal and steel enterprise decided to construct a new pit, in which the flow of operations could be optimized by automatization, thereby reducing the numbers of workers needed and increasing coal production to meet the target of 12 000 tons per day. As far as I know, Zollverein was the first pit in the world where the fordist mode of production was used in mining. In 1926 the enterprise instructed two young architects, Fritz Schupp and Martin Kremmer, to design a new coal mine together with the mining engineers.[1] After three years of construction the new shaft number 12 went into operation. It was then considered the largest, most beautiful and most productive pit in the world.

The architects were able to plan the central Zollverein site around shaft 12 as a unified whole. They arranged the individual buildings according to the production process and gave them a uniform design, which they developed from steel frame construction. A characteristic feature is a supporting steel frame with a self-supporting curtain wall suspended in front of it. The thin exterior walls comprised a steel-framework filled in with bricks or armoured glass intended solely as protection against the elements.

The mine was closed in 1986, not for lack of coal, but because the price of the coal produced there could not compete on the world energy market. At the same time, the vast site (100 hectares, 280 buildings) was declared a national heritage site. The new history of Zollverein as a monument to Germany's industrial culture started then - and with it came a mountain of problems, particularly financial problems. The enterprise and the city of Essen had originally planned to tear the complex down and turn it into a site of industrial and construction rubble. The story ended with the declaration of Zollverein as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2001. Since then the federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia and the city of Essen have been working to turn the site into a monument to structural change in the Ruhr, encompassing design, architecture, history, business, education and tourism.

In 2010 the Ruhr was the European Capital of Culture and the Ruhr Museum (formally an old town museum) was inaugurated. Zollverein developed into an icon of industry in the Ruhr and a testament to its transformation.

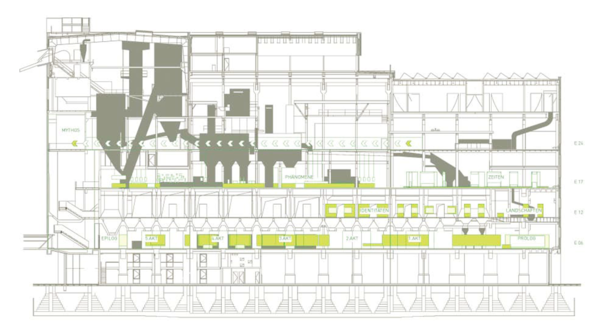

The coalwash is the biggest building at Zollverein. It is 90 meters long, 35 meters wide and 45 meters high at its highest point. A coalwash is used to separate coal from stones extracted from seams approximately 1000 meters deep. The so-called raw coal is poured into the machinery on top of the building and then transported further down to be separated using water (hence wash!). Both materials, the stones and the coal, are then classified by size and quality. Further down, they are stored in bunkers before being spilled onto conveyor belts. From there they are distributed to heaps (stones) or to customers (coal). Coke is needed to produce steel.

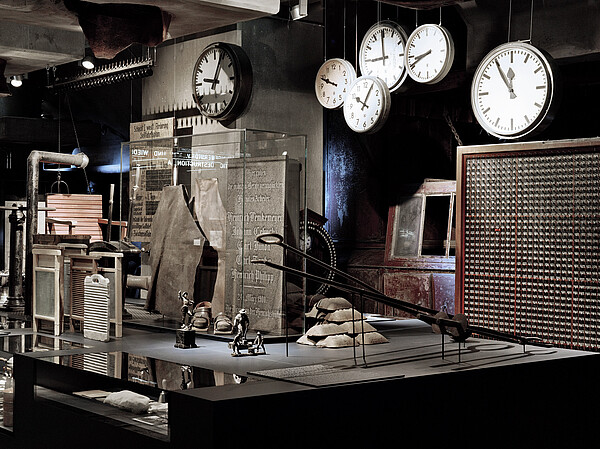

A coalwash is actually not a building, but a huge machine. It's not easy to convert a machine into a museum. The fact that a machine does not have an entrance presented us with a problem. The workers used to climb into the machine using a simple steel ladder. But the architect Rem Koolhaas understood that the museum had to have an entrance, preferably one that was also the exit. The solution was simple but not cheap. The museum treats its visitors like the miners treated the raw coal. (Conversion of a coal refinery into a museum and visitors centre) They are "poured" into the building from the top - having ascended a steep escalator - and then simply follow where gravity takes them, digging deeper and deeper into layers of history. (Masterplan for a former mining and coal refinery area) If we compare a coalwash with a museum, we find that they are actually quite alike. The work carried out by the machinery is really a process of refinement. As a museum, we want visitors to leave our museum more 'refined' than when they entered it.

The coalwash, an old industrial building, now a monument, was a challenging subject for an exhibition design. It was important not to change the existing spaces and surfaces. Machines had to be kept and integrated into the exhibition, preferably without touching them. On the other hand, this is what makes the museum so special. When constructing the exhibition, we had to make various compromises, even with regard to its content. A newly built museum would not have been so full of character. Therefore the guided tour of the exhibition follows the former flow of the coal, from top to bottom. We could not have conceived the museum against its old structure; the spirit of the coalwash resisted all attempts to use it differently.

The new museum's predecessor was a museum founded in 1904. Some of the objects held at the new museum - but by no means all of them - stem from those times. Together with more recent collections, they form the reservoir of what we can show. Of course, we cannot show what we do not have, but luckily the museum has collections in the realms of:

It is a very disparate collection, with more than 4 million objects in total. Five thousand are on display in the museum, which boasts an exhibition space in excess of 5000 square meters.

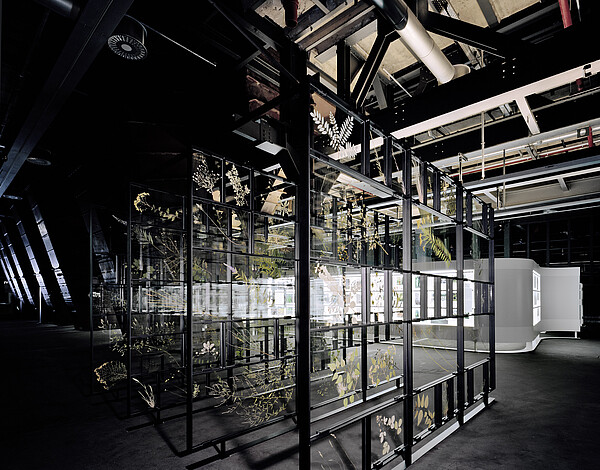

In the exhibition objects from the natural world are not separated from man-made objects. On the contrary, we dared to combine them in a kind of cross-over concept, a real hybrid. This was a museological risk, and we cannot claim to have been successful in all cases - the concept doesn't always work.

With very few exceptions the museum displays authentic objects. There are only a few reproductions and mock-ups, with no fakes or dummies and just a couple of new media stations (films and photographs are generally treated like objects). We avoided scenography and there are no imitations of "real situations" or theatrical effects. Instead, objects or groups of objects are shown in special contexts, accompanied by sparse texts. The presentation is not meant to overwhelm visitors - the building itself is overwhelming enough. We believe that the museum lays bare the constructedness of its understanding of history and does not stand on or presume to tell a single truth. You cannot experience the past like it "was", by no museological means.

The building's structure allowed us to present objects on three levels, with each level representing a different category: Gegenwart - Gedächtnis - Geschichte (Present - Memory - History). The tour starts in the present and ends in the present. The rationale for combining certain levels with certain categories is explained to the visitor in a short introductory text. The museum uses a range of texts, from the texts that provide an overview of each level, to the chapters and sub-chapters, and the shorter texts that describe groups of objects and individual objects. Each kind of text must be of a certain length. This rule has not been easy to observe, given the number of curators who worked on the concept.

The discourse on memory in cultural studies played an important role in our reflections on the exhibition concept. The whole process got under way 10 years prior to the opening of the museum in 2010. In the first stage of this conceptual work, we organized a series of lectures and a big congress on museology. We wanted to get to know the various academic positions in all of the fields relevant to the museum - especially in epistemology and museology and in the debate on memory, remembering and forgetting. To ensure we wouldn't make any major mistakes, we formed an advisory board with twenty specialists of all kinds. This board accompanied, commented on and corrected our work over four years until the museum was opened.

On the "Present" level the museum presents (among other things) objects connected to personal memories. Altogether, they represent the collective (communicative) memory of the Ruhr area's currently living population. Unlike the objects from our natural history collections, each of these objects tells a story from a person's life. Thus, the visitor is confronted with two vastly different temporal perspectives: the blink of an eye meets "eternity". Irony is, by the way, one of the narrative modes used to represent the region's character. We like to make fun of ourselves, our local dialect, our religion called football, the practice of breeding animals in the backyard, the sports you can only find here, and our provincialism in general. And people like that too.

On the second level, "Memory", the museum deals with the cultural memory of the Ruhr area, with a past we cannot remember ourselves, which is handed down by tradition and other layers of identity (e.g. the identity of towns). We don't have many objects from these times in our collections. Therefore, the principle followed in this part of the exhibit is what I would call plausible pointillism. (We could have filled the gaps with animated media, but as we do not - in general - use media that were not used in the times represented, we decided to leave these gaps empty.) Objects that hint at the pre-industrial times of this landscape a long time before man irreversibly changed it are interspersed with objects from our civilization.

On the third "History" level the museum presents, mainly chronologically, the two centuries of industrial history from 1800 to 2000. We tell this story as a classic drama in five acts, introduced by a prologue and followed by an epilogue. There are 5 themes per act, with 25 themes altogether. This level looks at aspects of society (e.g. migration), industry (e.g. the Krupp steel works), politics (including violence and wars), mentality (e.g. religion), every-day life (e.g. housing), and work (e.g. of housewives). Nature is seen in three different roles: as a repository of raw materials (such as iron and iron ore), as a victim of devastation, and as a modern landscape making a slow recovery from human intervention.

Essentially, the museum displays its collections, but the objects are integrated into a train of thought - a Gedankengang. This train of thought follows the path of time (or the past) and also the discourse on memory. This may not be convincing in all cases, and we may not succeed in every single detail, but it is at least an attempt. In my view, the more we accept (and show) the gaps that result from the lack of objects, the more successful this attempt is. The lack of objects made it impossible to tell the "whole" (hi)story as an unbroken process, a continuous development. Museologists may even detect various historical forms of museological representation in our exhibition (e.g. the chamber of miracles).

Put into context by other objects and texts in the exhibition, the object is a source of historical cognition and knowledge. No object is used in the exhibition by mere chance, just because the museum has it. A museum is not just an "event" or a tourist experience. In operating with the perception and aesthetics of objects, museums call on our intellect. They are media of entertainment in so far as enjoying a museum can be understood as process of becoming smarter ("more refined"). In my view, history museums should open eyes, not lecture from on high. Rather than suggesting that there is a single historical truth, they should highlight the complexity of the past and the complexity of understanding the past. After all, understanding and representing the past is what history is all about. Museums do that using objects - something that is both difficult and complex. Yet they must not succumb to nostalgia, folklore, unquestioned tradition, false heroism, political goals, or compulsory identification. A museum should be a place of learning that is scrupulous, thoughtful, critical and sensual all at the same time.

Ulrich Borsdorf: The Ruhr Museum at Zollverein. In: Cultures of History Forum (05.06.2014), DOI: 10.25626/0025.

Copyright (c) 2014 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

Official webpage of the Ruhr Museum at Zollverein (in German)

Hans Gutbrod · 30.05.2023

Sebald's Path in Wertach -- Commemorating the Commemorator

Read more

Matěj Spurný · 31.10.2021

The Colour of Compromise: The 'Documentation Centre for Displacement, Expulsion, Reconciliation' as ...

Read more

James Krapfl and Andrew Kloiber · 28.05.2020

The Revolution Continues: Memories of 1989 and the Defence of Democracy in Germany, the Czech Republ...

Read more

Sabine Volk · 11.03.2020

Commemoration at the Extremes: A Field Report from Dresden 2020

Read more

Gespräch · 30.11.2019

"In Auschwitz hat sich die Wirklichkeit entlarvt" - ein Gespräch mit Daniel Kehlmann

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).