31. Oct 2021 - DOI 10.25626/0132

Matěj Spurný is a senior lecturer of social history at Charles University Prague as well as a researcher at the Institute of Contemporary History, Czech Academy of Sciences. His research includea intellectual, urban and environmental history in socialist Czechoslovakia as well as post-war Czech history of minorities and the construction of the communist dicatorship. He authored Making the Most of Tomorrow. A Laboratory of Socialist Modernity in Czechoslovakia (Karolinum Press, 2019) and Der lange Schatten der Vertreibung. Ethnizität und Aufbau des Sozialismus in tschechischen Grenzgebieten (1945-1960) (in German, Harrasowitz, 2019).

The path towards the realization of this museum was infinitely long. When the Documentation Centre for Displacement, Expulsion, Reconciliation finally opened its permanent exhibition on 23 June 2021, most of those involved agreed – all praise aside – that it was most regrettable that we had to wait so long for a central site of remembrance and musealization of the displacement and expulsion of Germans (initiated by Germany) after the Second World War.[1] Most of the people who had been affected by the historical events at the end of the war and in the months that followed are no longer alive. Many of them died over the course of the years in which the permanent exhibition, which, among other things, would ultimately exhibit their fate, was laboriously negotiated.

From the beginning, it was far from clear what the purpose of such a museum should actually be. Was it to assure the formerly expelled and their descendants that this chapter of German and European history would not be forgotten? Was it to maintain their memories; to comfort and to, perhaps, reconcile? Was it meant to integrate the forced resettlement of Germans after the War into a broader context and thus offer an alternative to traditional narratives promoted by the expellee organizations? Or was it, indeed, meant to critically question individual recollections as well as the collective memory of a part of German society? The initiators of the museum, the Association of Expellees (Bund der Vertriebenen - BDV) must have been aware that it was hardly possible to reconcile all these different aims and approaches under one roof in any meaningful way. Nevertheless, even from their perspective, it was important that this museum would not simply be some kind of self-help institution aimed solely at the former expellees and their descendants, who took an active part in post-war German memory politics. Rather, they aimed to create a documentation centre with a permanent exhibition that would be officially recognized by both the Federal Republic of Germany and the international community and thus have the capacity to appeal to a wider audience.

In the course of the preparations, it was precisely the international recognition that turned out to be a goal that was difficult to achieve, not least because of the controversial personality of the longstanding chairperson of the BDV, CDU politician Erika Steinbach. Above all, the Polish partners and observers feared that post-war flight and expulsion – that is, the Germans’ ‘own’ suffering – would now become central to the German memory landscape and overshadow the horrors of Nazi rule over Europe and the Second World War. In 2009, Polish historian Tomasz Szarota pointed out that

Germany should finally inform its society that the flight and expulsion of many people from their traditional areas is not the greatest misfortune of the Second World War. A much bigger tragedy was the expulsion from life.[2]

Szarota said this shortly before he resigned from the academic advisory board of the Stiftung Flucht, Vertreibung, Versöhnung (SFVV), a body created to organise the establishment of the Documentation Centre.

The resignation of Erika Steinbach from the Board of the SFVV in 2010 prevented the foundation’s collapse, but it took another seven years before the Board of Trustees agreed on a conception for the permanent exhibition in 2017. Another four years later, the agreed basic structure of the exhibition was finally implemented in the Deutschlandhaus situated near Berlin's Anhalter Bahnhof. According to the BDV’s and many other German decision-makers’ wishes, the main focus of the exhibition remained on the flight and expulsion of Germans. But the fate of the German expellees was contextualized in the permanent exhibition by way of showing a broader panorama of European and global forced migrations in the twentieth century.

It is precisely this European – and sometimes global – context that forms the first part of the permanent exhibition, situated on the first floor of the spacious building. The explanation that accompanies the events shown here is rather brief: the visitor is informed via an information board that nationalism often leads to exclusion or war, and that it is “above all armed conflicts” that “make flight and expulsion a mass phenomenon in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.” Other terms used in the permanent exhibition are also generally only superficially explained and hardly ever problematized, which is particularly surprising when it comes to the central term “expulsion” (Vertreibung). To capture all organized forced migrations during the post-war period under this term has been a clear strategy of the (West-) German historical policy (Geschichtspolitik) since the early post-war years. Indeed, it is not surprising that it is also this terminology that has been the source of controversy in German-Czechoslovak relations (since the 1970s) as well as, later, in German-Czech and German-Polish negotiations on finding a joint position vis à vis the assessment of the forced resettlements (Zwangsaussiedlungen or zwangsweise Aussiedlung) of the German population (for example, in the Czech-German Declaration from 1997).

In the exhibition, the ‘European and global contexts’ are displayed mainly by presenting brief characterizations of individual European national movements that are immediately followed by concrete case studies of forced migration, yet they do not provide any further explanation as to why they were selected and why they are presented this way. In some cases, a short, general piece of information is provided, for example, regarding the flight from East Prussia: “The Soviet offensive begins on 12 January [1944], and shortly thereafter the Red Army reaches the Oder. East Prussia is now cut off. The People are unprepared and afraid of being raped. Hundreds of thousands flee westwards.” By contrast, the murder of the European Sinti and Roma, which was often preceded by acts of displacement and expulsion, is exemplified with the deportation and murder of around 5,000 Roma from Burgenland. Yet nowhere is this tragic end of a community contextualized by way of information about the planning, execution and the extent of the Romani Holocaust (the Porajmos).

The scarce descriptions, whether more general or exemplary, are then occasionally accompanied by one or two documents or objects, sometimes also including someone’s life story. Still on the same floor, there are also larger objects on display, such as former expellees’ clothing or toys that were taken along by children, as well as photos taken by contemporary witnesses. Given that this is supposed to be the contextualizing part of the exhibition it is somewhat surprising to realize how many of the presented objects are about the German refugees and expellees, especially those from East Prussia. From a practical perspective, this may not be surprising because it is precisely these objects that the designers of the Documentation Centre had at their disposal; yet given the political rhetoric about the European character of this museum, the choice of objects does not necessarily lend much credibility to the enterprise. However, this is nowhere near the biggest problem of the Documentation Centre.

Long before the opening of the Documentation Centre, the well-known historian of Central and Eastern Europe and Director of the Munich Collegium Carolinum, Martin Schulze Wessel, had proposed that the first room should be dedicated to the Shoah:

In other words, a room that everyone has to go through before they can reach the free space in which the expulsions are represented. That would make it obvious in a museum-didactic way what the situation is like.[3]

Undoubtedly, there would be a whole range of possibilities, how the Holocaust, a genocide that involved, among other, the forced leaving of ones home as well as forced migration (to the ghettos and extermination camps all over Eastern Europe), could be displayed and explained in such an exhibition. However, the curators of this exhibition eventually solved the issue by mentioning the Holocaust in various places, mostly in the contextualizing part of the exhibition, but not making the Holocaust an issue in and of itself. Against the backdrop of German memory politics, this is, euphemistically speaking, rather surprising.

There are certainly many reasons why the Holocaust poses a problem, if not an obstacle for meaningfully conceptualizing a Berlin-based exhibition on flight and expulsion in the twentieth century. Ultimately, even the authors of the widely respected Lexicon of Expulsions[4] did not deal with the Holocaust (and genocide in general) in any convincing way either.[5] In the Documentation Centre’s exhibition, the topic is addressed, even if rather fleetingly, in the context of the National Socialist extermination policy on the second floor, thus at the beginning of the second part of the permanent exhibition about the flight and expulsion of Germans. But because of the strong presence of other victim groups such as the East Prussians in both parts of the exhibition, this argument loses its strength. The geographical proximity of the new Documentation Centre to the Jewish Museum and the Holocaust Memorial in central Berlin may have strengthened the (however illusory) feeling of the curators that the visitors possess a basic knowledge of the topic and that one can therefore merely refer to the phenomenon of the Holocaust in an exhibition about flight and expulsion in Europe of the twentieth century without going into any more detail. Another reason for this decision might have been the fear that both phenomena – the Holocaust and the expulsion of Germans from Polish and Czech territories – would be equated if addressed together.

Even though all these difficulties and dilemmas may be understandable, the almost complete disregard of the extermination of Jews in Europe in a German-made exhibition that is supposed to contextualize post-war flight and expulsion is very difficult to accept. Yet, the real problem lies deeper. It is exactly the juxtaposition of victim stories, something that was declared the principle of this part of the Documentation Centre (without, however, illuminating them by way of a critical analytical perspective) that makes it impossible to meaningfully integrate the Holocaust and modern genocides into such a one-dimensional presentation.

In contrast to the first, “European” part of the exhibition, the exposition of the forced resettlement of the Germans at the end of the Second World War (consistently termed “flight and expulsion” by the exhibition authors) is structured chronologically and thus follows and constructs a certain narrative. The broad lines of this narrative are hardly surprising and reflect the task at hand: to tell the story of the flight and expulsion of Germans as well as their arrival and integration in post-war Germany in the context of the atrocities and racist politics of annihilation by the Nazi regime. Other than in the part that is devoted to European (and global) contexts, in this section the authors clearly knew which story they wanted to tell. Since they also had enough objects to illustrate this story, the main purpose of musealizing a historical phenomenon is realized in a way that visitors can understand.

However, it cannot escape the eye of the more informed and attentive visitor just how much the concept is closely attached to the reproduction of what has been experienced, to telling and describing. In this way, a more compact story is knitted together. Yet, similar to the earlier part of the exhibition, the presentation falls short of questioning or clarifying the terms used, or the individual documents and stories displayed. Instead of questions, a full story is presented. To be sure, telling a narrative in an exhibition is in and of itself not necessarily a weakness, but the narrative presented here ignores many contexts and doubts that have already been formulated and discussed in the public for decades. This becomes particularly clear when one enters those exhibition rooms that depict the story of arrival and integration, as well as of the evolving memory culture of the expellees especially in Western Germany. Besides displaying a local Heimatstube filled with many personal memorabilia, the curators also present the public debates that address the issue of “expulsion”. However, the political and discursive role of the memory culture that was fostered by the various expellee organisations is hardly discussed, nor is it in any way problematized. Moreover, the visitor at times doubts to what extent the exhibition authors considered the critical historical debates and findings of recent years at all. Little reference is made to recent German expert literature, even less to non-German expert literature. Instead, the authors reference the 1950s source edition Documentation of the Expulsion of Germans from Eastern Central Europe and consider it “still important today”.[6]This affirmation is all the more surprising as both the political character of this enormous documentation project[7], as well as the involvement of its editors – especially Theodor Schieder and Werner Conze – with the Nazi regime have already been discussed for decades. During the Nazi era, Schieder and Conze were important protagonists of the politically and ideologically promoted Volksgeschichte, which, among other things, was supposed to historically justify German rule over East Central Europe and parts of Eastern Europe.[8]

These are certainly some fundamental weaknesses of the exhibition, which in many respects did not make sufficient use of the opportunity to thoroughly historicize the events, experiences and memories that it represents. Yet, aside from this, the parts of the exhibition that address the flight and expulsion of Germans also show an excessive concentration on just a few groups of expellees at the expense of others. This asymmetry is particularly evident regarding the more than three million Sudeten Germans. A glass cabinet is dedicated to their fate under the title “The German minority in Czechoslovakia.” Otherwise, the Sudeten Germans play a rather marginal role in the exhibition – especially when compared to the almost ubiquitous expellees from East Prussia. With regard to the people who were forcibly resettled to and integrated in Austria, the asymmetry becomes even more obvious, as they are hardly mentioned. Equally regrettable is the fact that the exhibition does not deal with the question of the consequences the forced resettlements had on the regions of origin; neither does it address the debates about such consequences nor the political instrumentalization of the expulsions in these regions, especially in Poland and Czechoslovakia. Perhaps the authors of the permanent exhibition wanted to avoid further controversy as this would have been yet another broad and possibly politically contentious topic.

Another clearly missed opportunity is that there is no ambition to combine the two levels of the Documentation Centre's exhibition – the “European” one on the first floor and the “German” one on the second – by way of addressing overarching themes. To give an example: it would have been possible to address the question posed in the first section about “who belongs to the nation” in the later section that deals with the flight and expulsion of Germans, and thus discuss the issue of national belong and nationality. All the more so since this question played an important role in the Nazi-occupied territories and countries after 1938; it also played a role in determining the fate of hundreds of thousands of families in Poland, Czechoslovakia and elsewhere during 1945/46. The notion that ‘Germans’ represented a clearly defined group in their countries of origin, a notion very much promoted by both the Nazi ideologues and the representatives of the post-war states, is hardly deconstructed, even though there would be countless documents and other possible exhibits showing the linguistic and national ambivalences in many of these regions. This is just one example – other categories that are formulated on the first level could also have been further clarified and documented ‘upstairs’, both through concrete stories and actions.

The building of the Documentation Centre looks both modern and simple. The architects had to expand on the original Deutschlandhaus, which is under heritage protection. The addition of a new building has been successful in so far as the combination of old and new does not disturb the visitor. The various parts of the Centre’s exhibition are spread over more than 5000 square metres, which also gives the visitors ample space – something that becomes particularly evident in the first part of the exhibition dedicated to the European context since this part is scarcely filled with objects. The contrast becomes even more evident upon entering the rooms of the exhibition that deal with German flight and expulsion, rooms filled with countless objects that make them appear far more crowded. The more clearly structured design of these exhibition rooms on the upper floor also support the previously-mentioned narrative about the fate of the Germans. The spaciousness and unclear structure of the lower level, which by contrast arouse a certain feeling of being lost, in turn corresponds well with the missing narrative in this part of the exhibition and thus underlines its fragmented character. This uncertainty and lack of guidance already starts at the very beginning upon entering the exhibition area.

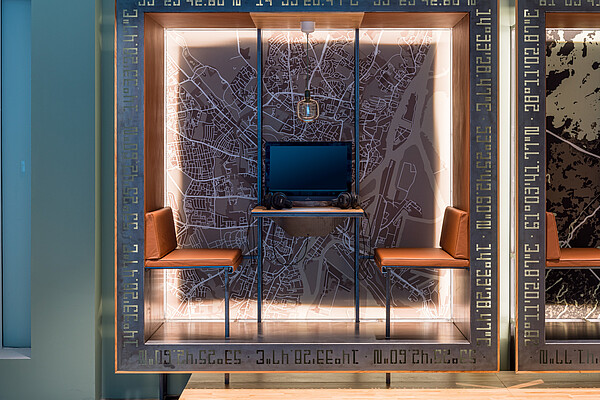

The main colour of the rooms on both floors is grey. The walls and the staircase are light grey; the showcases and the exhibition boards, as well as many other exhibition elements, are dark grey. Perhaps the designers wanted to let the texts and objects speak for themselves and not overshadow them with a colourful and imaginative design. To me, the grey colour and the rather bland visual impression of the museum is closely linked to the overall exhibition’s general cautiousness and the compromising that went on for so long before its doors opened. The technical and audio-visual possibilities that are supposed to help visitors absorb the content do not deviate from what has been common in European and other museums in the past two decades. One can listen to contemporary witnesses in many places, but sometimes one wonders how much sense it makes to offer hour-long or even longer recordings given the limited opening hours of an exhibition. But shorter excerpts from eyewitness testimonies are also available via video on large screens, which, as one can easily see, is much more attractive especially for younger visitors. There are drawers that can be pulled out as well as booths with computers and headsets to watch historical film material and listen to tape recordings. None of this is particularly original.

The room of silence, which is often mentioned in connection with the Documentation Centre, also leaves the impression that you are dealing with a somewhat weaker copy of something that already exists elsewhere. Indeed, the reference to the ‘Room of Silence’ in the Jewish Museum, not far from the Deutschlandhaus, is relatively obvious. There, visitors are confronted with a countless number of iron circles on the floor, which remind them of human faces, of the millions of human lives destroyed. The 100-square metre Room of Silence in the Documentation Centre, with its wooden floor and wooden panelling, is a pleasant, warm place and stands in stark contrast to the rather inhospitable rest of the building made of concrete. Perhaps it is supposed to remind one of a living room, or a lost home. If it does, this would be a good place for those affected to remember, to pause. For most visitors, however, the message and function of the Room of Silence remains unclear. I myself spent a relatively long time in this rather cosy room during which none of the many other visitors to the Documentation Centre entered.

It does make sense and is useful that there is a central site in Berlin, a Documentation Centre with a permanent exhibition, that deals with the subject of the forced resettlement and expulsion of Germans at the end of and after the Second World War. With its library and its archive of contemporary witness accounts, the Centre can become an important research hub for scholars, students, journalists and others who are interested in the subject of refugees and forced migrations in the past and present.

Fortunately, the permanent exhibition does not fulfil the greatest fears that were originally formulated in international and Federal German contexts: the 'expulsion' of the Germans is not taken out of its chronological and thematic context here. There is no new multi-Heimatstube at the Deutschlandhaus that would only preserve und musealize the memories and discourses of the former expellees.

Nevertheless, the result of the extended and arduous work of so many cultural managers, historians, curators, museum educators and other experts can only be described as disappointing. With a politically sensitive issue such as this, it is legitimate to expect that a central permanent exhibition not only reproduce what has been experienced, but also demonstrate critical distance from the politically contentious narratives. Yet, the uncritical adherence to the central concept of ‘expulsion’, the adoption of the categories of nationality as used in the 1930s and 1940s without deconstructing them, and the reproduction of the memory culture of those affected in post-war Germany without discussing how this memory was used politically and how it influenced the public discourse in the Federal Republic of Germany, all show that a great opportunity has been missed here.

Thirty years ago, the story of the ‘flight and expulsion’ of the Germans after the Second World War told in the context of the Nazi occupation and extermination policy and accompanied by insights into other European and global examples of forced migrations – even if selected according to unclear criteria – would certainly have been something extraordinary in Germany's memory landscape and politics. Yet, more than seventy-five years after the events that are represented in the museum, and more than thirty years after the fall of the Iron Curtain, this painstakingly negotiated museum seems more like a belatedly fulfilled obligation.

Matěj Spurný: The Colour of Compromise: The 'Documentation Centre for Displacement, Expulsion, Reconciliation' as a Negotiated Museum. In: Cultures of History Forum (29.10.2021), DOI: 10.25626/0132

Copyright (c) 2021 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

See these "first impressions of the new exhibition 'Displacement, Expulsion, Reconciliation'" provided by the Docuumentation Centre to the Press in June 2021

See also the 2015 video by the Foundation “Flucht, Vertreibung, Versöhnung” about the plans for the new Documentation Centre

Hans Gutbrod · 30.05.2023

Sebald's Path in Wertach -- Commemorating the Commemorator

Read more

James Krapfl and Andrew Kloiber · 28.05.2020

The Revolution Continues: Memories of 1989 and the Defence of Democracy in Germany, the Czech Republ...

Read more

Sabine Volk · 11.03.2020

Commemoration at the Extremes: A Field Report from Dresden 2020

Read more

Gespräch · 30.11.2019

"In Auschwitz hat sich die Wirklichkeit entlarvt" - ein Gespräch mit Daniel Kehlmann

Read more

Gespräch · 17.05.2019

Revisiting the TV-Series “Holocaust” Thirty Years On

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).