30. May 2023 - DOI 10.25626/0146

Hans Gutbrod is an Associate Professor at Ilia State University, Tbilisi, Georgia, and also teaches at the University of Bamberg. He holds a Ph.D. in International Relations from the London School of Economics. His current research focus is an Ethics of Political Commemoration. Dr. Gutbrod was the Regional Director of the Caucasus Research Resource Centers (CRRC) from 2006-2012 and has been working in the Caucasus region since 1999.

Writers often play a major role in the national imagination. They tell stories that resonate with many people and that can become representative of national experience. Their own fates, too, often connect to a country’s history. Next to banning books, repressive regimes often target writers themselves. In that way, writers can be deserving of commemoration not only for their writing, but also for what they mean for a place or even a country.

A standard form of commemoration for writers Is the house museum, which collects artefacts of their lives and showcases where they worked. This model is well established and can also evoke a context of persecution – such as for many writers of the Soviet period, including the Armenian poet Yeghishe Charents (1897 – 1937), who were arrested right in their apartments. Many did not survive the purges.

Such house museums, however, have their limitations. It is not always possible to recreate a compelling ambience. Sometimes, relevant locations — such as a writer’s birthplace — are not connected to the writer’s subsequent workplace. Not all writers have the standing of Thomas Mann, whose memory commands five museums across four countries. Not all locations unite, as the Goethe House in Frankfurt does, a historical monument, a stately eighteenth-century building, and the location where the young Goethe wrote The Sorrows of the Young Werther (1774). Keeping a good commemoration going is a question of resources, too. Certain house museums can be a sad and dusty affair. They diminish rather than engage with – or even elevate – an artist’s work.

How then to deal with the memory of writers for whom a museum seems less apt? One model of commemoration that arguably deserves greater attention is the ‘Sebald Path’ near Wertach, in southern Germany. W.G. Sebald (1944–2001) is one of Germany’s most internationally cited authors in recent memory, and also an author with a strong interest in memory. His landmark works, Die Ausgewanderten (“The Emigrants”, 1992) and Austerlitz (2001), are usually described as tales of displacement and loss. Central to his writing was the question of how to deal with the Nazi-German past in a society of former perpetrators. Much of his work thus explores the “effects political persecution produces in people fifty years down the line, and the complicated workings of remembering and forgetting that go with that”.[1]

The Sebald path in Wertach succeeds in commemorating this commemorator. While it is also fragmentary and incomplete, these shortcomings can be seen as evocative, as they can nudge visitors to try and fill out the considerable gaps in their encounter with the path. This echoes how Sebald as a writer (a “contemporary master of the literature of lament and mental restlessness”, according to Susan Sontag) sought to unsettle his readers.

As Sebald said in one of his last interviews in 2001, what he was attempting was “the opposite of suspending disbelief and being swept along by the action”. Instead, he wanted to evoke loss and absence, and, with reference to the displaced, to force readers “to constantly ask, ‘What happened to these people, what might they have felt like?’ You can generate a similar state of mind in the reader by making them uncertain.’” Yet within that attempt to unsettle there was a constructive vision, too. In a speech a few weeks before his sudden death in 2001, Sebald suggested that there “are many forms of writing; only in literature, however, can there be an attempt at restitution over and above the mere recital of facts, and over and above scholarship.”[2]

Sebald was born in Wertach, a village on the northern rim of the Alps, near the Austrian border. He grew up in the village and in nearby Sonthofen in the Allgäu region, before leaving Germany to study first in Switzerland and then in the United Kingdom. Here he spent most of his professional life, eventually teaching at the University of East Anglia. Sebald came to prominence in the early 1990s, in his mid-40s, having forged a distinctive style and approach to literature. As a writer, he only received wider attention for about a decade, before dying in a car crash.

Wertach and southern Germany connects to Sebald’s story as his place of birth and as the backdrop in some of his writing, but it is not the main place connected to his work. In this regard, Sebald’s trajectory runs parallel to other authors who were drawn to more urban centres or even to emigration and of whom not many physical traces remain.

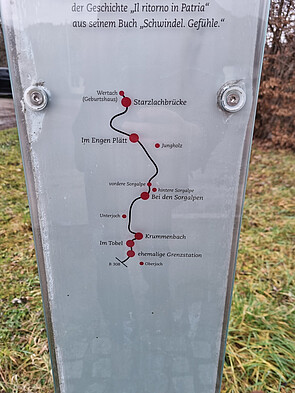

The main way to visit Sebald in Wertach is to go on the “Sebald Weg” that runs from a former border post on the Austrian border, close to the mountain village of Oberjoch, descends down to Wertach at a mostly gentle incline, through forests and meadows, past Alpine farmsteads and along a busy stream. Along the well-marked path, about 12 km long, there are a total of six stelae that draw from the Sebald story Il Ritorno in Patria, in which he describes a hike on a November day in 1987, upon returning to his native village after many years of absence. (The title seems to be a play on the title of Claudio Monteverdi’s 1639 opera of “Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria” with Sebald as a “Ulysses” of sorts, returning from an odyssey.)[3] In the story, Sebald leaves the bus up on a mountain road as there is no direct connection to his village; arranges with a customs official to bring his luggage down to “W.” (as Wertach is described in the story), and sets off to walk the remaining distance. Il Ritorno in Patria is the last chapter of Vertigo (1990), which in the original German carried the title Schwindel, Gefühle – a more ambiguous title in the original, which can also be translated as feelings of dizziness, or even as swindle and feelings.[4]

The stelae, lean and made of metal, display text passages linked to their respective location: the forest, a small waterfall, a clearing, a chapel, a narrow gorge and eventually a bridge into the village of Wertach itself.

We – a group of friends, including children – started the Sebald path on one of the last days of December 2021. The timing was its own comment on our present day: Sebald’s walk in November had been marked by snowfall, and normally the Sebald path is only open from spring to fall. Now, only artificial snow kept some of the ski slopes in Oberjoch open, odd white bands snaking up the dark green hill. Later, we would pass ski lifts that stood entirely still. (A later radio version of Sebald’s story added a mysterious fellow passenger and Doppelgänger who discusses the debacle of a world in which it no longer snows.)

The starting point of the walk can be tricky to find if the tourist office in Wertach is not open and can explain where to go. The most plausible starting point, when arriving by car, are the large parking lots that serve mountain tourists at the bottom of the Oberjoch lifts.

By the first stela, close to what used to be a patrolled border between Germany and Austria and now — with the exception of the brief reappearance of such divisions during the Covid-19 pandemic — seems like merely a boundary stone in the forest, one member of the group read out the text as everyone else scanned along.

The children enjoyed the hike, with its meadows to run across and little side adventures, such as a small climbing wall along the path. Lacking snow, they threw mud into the stream, chased each other, and one of the boys eventually cleaned his hands by wiping them off on the white walls of the little Krummenbach chapel described in a stela. With reference to the chapel, Sebald wonders whether the Venetian painter Tiepolo had stopped by, on his way across the Alps to Würzburg, where he would paint some of his most magnificent works.

Walks are more likely than museums to create their own new stories. Further down, a car drove up to us, and the people introduced themselves as neighbours and caretakers of the chapel and complained that they had just painted it this year — was it really necessary to smear it with mud? After our acknowledgement and apology, they moved on, still disgruntled, but the incident lingered, with vague plans to return to scrub the walls later during the vacation. The adults wondered, too, whether the children had fully understood that this kind of micro-vandalism was not on. The muddy smudge could itself represent intersecting concerns and tensions, from which you could tell a bigger story of the people on the walk and what was going on in their lives.

After the fourth stela, the children were tired and were taken home. I continued alone to the next stela at the beginning of a narrow gorge called “Engen Plätt”. In its text, Sebald’s existential theme emerges:

In April 1945, a so-called last skirmish took place in the Engen Plätt, in which, as it says on the iron memorial cross which still stands in the cemetery in W., the 24-year-old Alois Thimet from Rosenheim, the 41 -year-old Erich Daimler from Stuttgart, the 17-year-old Rudolf Leitenstorfer (place of birth unknown) and Werner Hempel from Börneke (year of birth unknown) died for the Fatherland. In the course of my short childhood in W. I heard people speak of that last skirmish on various occasions and imagined the combatants with soot-blackened faces, crouching behind tree trunks with their rifles at the ready, or leaping from rock to rock across the deepest chasms, suspended motionless in the air, for at least as long as I held my breath or didn’t open my eyes.[5]

Passing through the gorge, not holding one’s breath and keeping one’s eyes open, between rocks and chasms, hikers can ponder the futility of dying in these last weeks of the war, as did these four out of the millions lost to a murderous regime – though these men also wore the uniform of the perpetrators. In attributing the words to others, Sebald distances himself from what falling for the Fatherland could possibly have meant in the Nazi-German context.

Distancing himself from an unexamined mainstream was perhaps also more broadly Sebald’s attitude. In a 2001 radio interview, Sebald said that he liked “to listen to people that have been sidelined for one reason or another because in my experience once they begin to talk, they have things to tell you that you won’t get from anywhere else”. Growing up in postwar Germany, Sebald continues, there was a conspiracy of silence, and a great deal of shame. Even between each other, his parents had not talked much about the immediate past. Consequently, he had “grown up feeling that there is some sort of emptiness somewhere that needs to be filled with accounts from witnesses that one can trust”. Yet at the same time, “the people who could tell you the truth, or something at least approximating the truth no longer existed in the country”.

His best-known books, Emigrants and Austerlitz, revolve around that loss and that memory of loss, as well as those lost memories, centred around mostly Jewish protagonists. Some of the rendering of loss is oblique. In that 2001 radio interview, Sebald invokes Walter Benjamin’s suggestion that

there is no point in exaggerating what is already horrific and, from that, by extrapolation, one could conclude that to get full measure of what is horrific one needs to remind readers of beatific moments of life; if you, as it were, existed solely with your imagination in the monde concentrationnaire you would somehow not be able to sense it; [...] it requires that contrast; and the old-fashionedness of the diction or the narrative tone is nothing to do with nostalgia for a better age that’s gone past, but it’s simply something that heightens the awareness of what we have managed to engineer in this century.

On the path itself, nature provides the stark contrast to Sebald’s more ominous themes of loss.

The last stela, at the entrance to Wertach, tells the story of the large sawmill burning down in 1950, in the year in which Sebald enters school. The fire consumed the mill and all its stored wood, lighting up the entire valley. In the story of his return after many decades, night has fallen, and, as per the stela, Sebald writes that “I realized suddenly that I could hardly lift my feet anymore because I was so tired.”[6]

Those who read Sebald’s work might recognize that fire is central to his imagination, first and foremost with reference to the Holocaust (denoting, in Greek, a burnt sacrificial offering), and then later in his writing about the firestorms that engulfed German cities as a result of aerial bombing during the Second World War.[7] The seemingly parochial reference to the sawmill is also a comment on political obliteration. One of Sebald’s themes is that such murderous politics are not something that arrives from far away Berlin, but also manifests locally – in one’s own community and family.

Fire is Sebald’s main element, as Uwe Schütte, Sebald’s only former Ph.D. student, has noted in an essay on Sebald’s work.[8] Next to its political dimensions, Sebald repeatedly writes about flames, whether the Great Fire of London of 1666, or Franz Kafka’s order to burn his unpublished manuscripts, which he discussed with the writer Elias Canetti. The central role of fire, as Schütte highlights, is also underlined in Sebald’s statement that he “admire[s] ash very much. The very last product of combustion, with no resistance in it. The borderline between being and nothingness. Ash is a redeemed substance, like dust.”[9]Il Ritorno in Patria ends with a dream, in which the narrator recalls the words of Samuel Pepys as he describes the aftermath of London’s fire: “And, the day after, a silent rain of ashes, westward, as far as Windsor Park.”[10]

After completing the route, it is not entirely clear where to go next. I walked through Wertach in search of other traces of Sebald. At first, no one I asked seemed to know where to find Sebald’s birth house and only by accident did I finally find it. Indeed, a little plaque on the house highlighted that this was where Sebald was born on 18 May 1944. There was also a mural on the house that displayed Götz von Berlichingen, a sixteenth-century imperial knight, mercenary, and poet of southern Germany. Having lost part of his arm, von Berlichingen was also famous for his prosthetic iron hand. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe wrote a play about him, anchoring him in German literature. Though known for his drastic pronouncements, von Berlichingen adhered to a code of chivalry. By contrast, the SS-division named after him, which styled itself with a clenched iron fist as its emblem, committed multiple war crimes across France and Germany. The mural is crude; the Berlichingen castle is still a going concern a few hundred kilometres away. Why keep a reminder of Berlichingen here, on this house, and not replace him with Sebald?

After the commanding direction of the path, it seemed that Sebald peters out in Wertach. If there is more Sebald signage, it is hard to uncover. There was no art in the village’s park that recalled him, nor a bust or a QR code at the birth house. At least the Wertach public library holds his books and clippings, and as well as international editions gifted by visiting translators.

The way in which Sebald is incompletely remembered in the village stands in striking contrast to how, say, Hermann Hesse (awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1946, in part because as a German writer he kept a strident distance from National Socialism and because he exemplified “classical humanitarian ideals”) is celebrated as an identifying figure in Calw, Baden-Württemberg, his birthplace.

My quick visit left the impression that it would not be hard for the village to also reinvent itself based on some of Sebald’s themes: “Wanderdorf Wertach”, a village ideal for a walking and hiking vacation; a village of emigration, as Sebald and his relatives, who had departed for the United States earlier in the twentieth century, had done, but also of immigration, as exemplified by the Pizzeria Colosseum, just a few steps away from where Sebald was born. Every other year, one could commission a small piece of art and enrich what otherwise seems like a fairly empty drive-through village.

Some have written that Sebald’s texts consist “almost entirely of digression”.[11] That digressive tendency would have left much amplitude for the municipality to develop ideas around his work. It is puzzling why the village restrains itself from connecting more to the person who most put it on the international map. Is it too small to hold and keep people who read books? Maybe one cannot expect much from a place with fewer than 3.000 inhabitants. In the state of Bavaria, mayors of small municipalities seem to receive a salary, but there is likely not much of an institutional framework for cultural affairs.

Carole Angier’s recently published Sebald biography affords a closer look at the author and his life.[12] This first comprehensive biography reveals that Sebald, as is already apparent in Il Ritorno in Patria, had a complicated relationship with the place he came from.

Quite a few people in Wertach felt that the author had thrown his hometown under the bus, so to speak, when it helped him make (or as critics might say: score) a point. Reading more about Sebald’s life and his distortions did, at first, not endear me to the author. Some of the landscape descriptions along the path suddenly seemed hyperbolic when compared to where one actually stood. Was it really a “waterfall”? The stream did not seem to pour down more water than what a full bucket might hold. Schütte, his lone disciple, also comments on how Sebald blurred facts.

On another level, that blurring also makes Sebald more intriguing. Alex Harvey notes that for Vertigo, the collection in which Il Ritorno was published, the “narrator, as in all his books, is and isn’t Sebald; he’s always transforming the actual, in his presentation of self or the world, into wider fiction.”[13] An attentive read shows that Sebald threaded references to Kafka, Stendhal, and other writers into Vertigo.[14] It is not just the narrator that we become successively less certain about. Harvey cites Michael Hamburger as saying that in Sebald’s work, “fact and fantasy or dream co-exist” and adds that “his writing is held together not by biography but by thematic imagery and an allusive reading of history.” Sebald’s inauthenticities perhaps also balance against canonization and undermine hagiography.

Locations mattered to Sebald. In a long feature by the critic Maya Jaggi, three months before his death, Sebald is quoted as saying that places

seem to me to have some kind of memory, in that they activate memory in those who look at them. […] It’s an old notion - this isn’t a good house because bad things have happened in it. Where I grew up, in a remote village at the back of a valley, the old still thought the dead needed attending to – a notion so universal it’s inscribed in all religions. If you didn’t, they might exact revenge upon the living. Such notions were not alien to me as a child.[15]

One could say that the Sebald path helps hikers to read and readers to hike – and through that process to immerse themselves more deeply in the life and work of a writer than they otherwise might have done. I certainly had a richer and more complicated picture of Sebald after hiking the path, which drew me to read more, to try to understand Sebald’s partial absence from Wertach. The more complicated historical and mnemonic dimensions of Sebald’s work are, perhaps, not so directly visible on the path, but they become apparent once you start reading.

Yet how should we think of the commemoration of writers more broadly? How can we judge whether it succeeds? Much as Sebald mistrusted frameworks, are there more systemic ways we can think about how to approach the memory of writers?

One such framework could be the Ethics of Political Commemoration, adapted from the Just War tradition. Drawing on this philosophical tradition reflects, remembrance is often conducted with political – and even coercive – intent, to tell or ascribe stories that in themselves are not fair or accurate descriptions of other people.

With its Ius ad Memoriam (what to commemorate) and Ius in Memoria (how to commemorate) criteria, the framework looks to guide debates that are currently inchoate so that remembrance of the past can transform relationships in the present and build a shared future. Together with colleagues, I have been working on this framework in recent years, and have applied it to national discussions of remembrance, including on museums in Croatia, Georgia, and beyond.

Using the Sebald path, it is possible to demonstrate how that multidimensional framework would apply (its criteria are in written in italics). Under the considerations of Ius ad Memoriam, the path has a good cause – Sebald deserves to be remembered, especially in Wertach. Next to its aesthetic impulse, his writing seems to have the good intention of helping Germany reckon with its past, and more generally “listen to people that have been sidelined for one reason or another”. Remembering him keeps that engagement going. As it is done there, the commemoration has a solid chance of success: it can engage people and expand the circle of people who are engaged. At the same time, the definition of success needs to be identified anew for each context.

For communities discussing how writers can be commemorated successfully, such a guiding framework allows them to generate new ideas as well. In Georgia, for example, the Museum of Repressed Writers in the centre of Tbilisi, could be complemented with ways of engaging with some of the poets (many of them indeed hounded) in the more peripheral places that they came from, beyond setting up another statue, or opening another museum that may well remain forsaken for want of interest. A broader public discussion would be important precisely so as to give such commemoration legitimate authority in their own communities.

Under Ius in Memoria, the Sebald path seems to fit the consideration of transforming the collective. Walkers are provided with the opportunity to ponder not only Sebald, but also 17-year-old Rudolf Leitenstorfer, as the representative of individual loss in that senseless defence of the gorge in April 1945. The commemoration works because it undermines and exits circular narratives of collective affirmation. These are individual experiences of walking (“the things that you pick up by accident are never less than unique”[16]), not of marching in a line, nor of an ordered pilgrimage. In allowing people to approach and engage on their own terms – and to leave early when they are tired – such an experience can help assert moral autonomy. It is an experience for citizens rather than subjects. No entrance ticket is required. Sebald’s fractured relationship to his home, and to some of his subjects, is part of the process of locating moral consideration in the walking reader and in the reading walker, rather than enshrining it with the writer. Lastly, there is a degree of contained unfathomability– there is something moving and even unfathomable in engaging with a writer that remains elusive in Wertach, who himself found an abrupt end. And yet that encounter is contained in a specific time and place, with the stelae and the gorge of the Engen Plätt.

Beyond our instinctive response (did we enjoy the walk or not?), the multidimensional framework of the Ethics of Political Commemoration illuminates why this path succeeds as commemoration. Such multi-dimensional criteria will be needed when, in other contexts, we seek to remember not only what was written, but also who wrote it and why we should care.

At the entrance of the Goethe Museum in Frankfurt, there is a piece of antique furniture I had not known about before: a so-called “Brandschrank” – a fire cabinet in which inhabitants, in the days before effective fire engines and water on tap, could collect valuables to carry outside in case the house was ever set ablaze. One suspects that Sebald would also have found such fire cabinets of interest.

At a time of democratic backsliding, literature and writers might matter even more than before. They are their own fire cabinets. As Jean-Jacques Rousseau suggested to the people of Poland 250 years ago, culture is what might see a people through even prolonged periods of oppression. For that reason, the question of literature and writers, and how to remember them well, is not just about valuing the past but also about securing the future.

Hans Gutbrod: Sebald's Path in Wertach -- Commemorating the Commemorator, Cultures of History Forum (30.05.2023), DOI: 10.25626/0146.

Copyright (c) 2023 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editor.

Matěj Spurný · 31.10.2021

The Colour of Compromise: The 'Documentation Centre for Displacement, Expulsion, Reconciliation' as ...

Read more

James Krapfl and Andrew Kloiber · 28.05.2020

The Revolution Continues: Memories of 1989 and the Defence of Democracy in Germany, the Czech Republ...

Read more

Sabine Volk · 11.03.2020

Commemoration at the Extremes: A Field Report from Dresden 2020

Read more

Gespräch · 30.11.2019

"In Auschwitz hat sich die Wirklichkeit entlarvt" - ein Gespräch mit Daniel Kehlmann

Read more

Gespräch · 17.05.2019

Revisiting the TV-Series “Holocaust” Thirty Years On

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).