24. May 2016 - DOI 10.25626/0051

Piotr Osęka is a historian and columnist, an associate professor at the Institute of Political Studies, Polish Academy of Sciences, and author of several books. He has also published numerous articles on twentieth-century history, totalitarian propaganda and the history of communist Poland – both in academic journals and Polish newspapers. His book on the collective biography of the Polish generation of 1968 ("My, Ludzie z Marca") appeared recently.

This news dominated Polish newspaper headlines for several weeks: on 16 March 2016, the media reported that attorneys from the Institute of National Remembrance (INR) had entered the flat of the late Czesław Kiszczak who had been Minister of Internal Affairs from 1981 to 1990. Television, radio and online media provided constant breaking news coverage, as if the police were chasing a dangerous criminal. At the start, the attorneys had just left Kiszczak’s home when several minutes later, a number of former Security Service documents were seized during a search. The next newsflash suggested that the documents might contain evidence of Lech Wałęsa’s collaboration with the secret police, including handwritten letters denouncing colleagues from the Gdańsk Shipyard.

The country was abuzz. Almost immediately, the INR provided journalists with photocopies of the seized materials. This procedure normally takes several weeks but was cut down to two days in this case; and instead of just one, ten sets of documents were compiled.

A throng of journalists and TV crews gathered outside the Institute. A few hours after the reading room had opened its doors, the Internet was flooded with pictures of individual documents from Wałęsa’s file. "There you have it", gloated the pro-PiS (Law and Justice party) media: "This is definitely the end of the Third Polish Republic" and "the end of the Round-Table Republic."

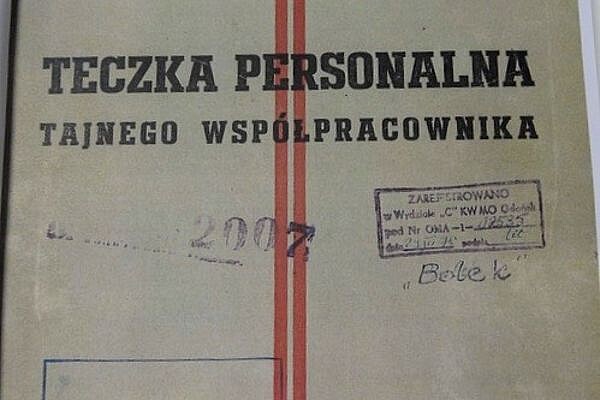

The documents found in Kiszczak’s flat contained nothing sensational per se. Wałęsa's CV had long been known to include a stint of collaboration with the Security Service (although he categorically denied this). The disputes were mostly over how deeply he was implicated. Historians and journalists sympathetic to the former president believed that, in December 1970, Wałęsa had been coerced by the secret police into signing a cooperation agreement (adopting the codename "Bolek"), but soon found the strength to extricate himself from involvement. The circumstances under which he was blackmailed also play into Wałęsa's hand – as one of the strike leaders at the Gdańsk Shipyard in December 1970, he rightly feared harsh reprisals against himself and his family. For instance, a similar interpretation can be found in Andrzej Wajda's well-known film Wałęsa: Man of Hope.

In turn, Wałęsa’s opponents maintained that, since the future Solidarity leader had been an ardent Security Service informer in the 1970s, shamelessly blowing the whistle on his friends for money, his collaboration with the secret police had shaped his subsequent political career. This theory was put forward in 2008, for example, in the book The Security Service and Lech Wałęsa: A Biographical Addendum by INR historians Piotr Gontarczyk and Sławomir Cenckiewicz. It overtly suggests that the round-table talks and the collapse of communism in 1989 were a process orchestrated by the Polish Communist Party leadership who were able to blackmail Wałęsa.

Gontarczyk and Cenckiewicz’s book was also highly circumstantial. The authors had analysed excerpts from Wałęsa’s denunciations stored in police files, but were not in possession of the most vital document – the so-called "personal file on secret collaborator Bolek", which was known to have vanished under odd circumstances from the Ministry of Internal Affairs archives in the late 1980s/early 1990s. That very file was found in Kiszczak's flat.

In some respect, the discovery was disappointing for both sides. On the one hand, the file’s several hundred pages are rather difficult and sad to read. Wałęsa had clearly supplied the secret police with details on the situation at the shipyard for several years, and named instigators among the workforce. In addition to his denunciations, he also received regular payments. On the other hand, however, the materials explicitly show that Wałęsa broke-off his collaboration in the mid-1970s and became involved in opposition activity. The final document in the file is dated June 1976. From that point onwards, Wałęsa ceased to be an ally of the Secret Service and instead became their enemy.

Once again, it has transpired that the narratives regarding the past that are 'aired in public' depend on whichever party is currently in power. For Wałęsa’s opponents (who are chiefly PiS supporters), the main issue was not that the former president had written the denunciations, but that the files had lain in the hands of an ex-Minister of Internal Affairs for the past quarter of a century.

"Kiszczak’s cupboard" became the missing link for the right-wing narrative which claims that the post-1989 transition was in fact engineered by the communist authorities who had managed to install Security Service informers in key posts in the new Poland. Thanks to various documents that had been spirited away, former police officers were purported to be controlling life in society and the economy of the Third Polish Republic from behind the scenes. This vision was first articulated in 2000 in the book Privatizing the Police-State: The Case of Poland by Andrzej Zybertowicz, a sociologist and journalist regarded as one of PiS’s principal ideologues.

For the "nationalist patriotic camp", obtaining Wałęsa's files from Kiszczak's flat was an event on a par with finding the Holy Grail. An elitist conspiracy had been unearthed: an alliance of ex-dissidents and former Security Service agents, sealed by a secret pact concluded in 1989. The "engineered transition" story stirred up even more emotion since a sizeable collection of photos (some of which were published) from the Magdalenka talks near Warsaw were also found among the former police chief's papers. They showed a round-table session at which opposition leaders were negotiating with representatives of the authorities.

"At the beginning, [Wałęsa] helped to preserve old connections. Later, he became a puppet in the hands of the newly appeared, parasitic, power 'układy' [alleged underhand schemes and deals] to keep society from peeking behind the scenes of the machinery", declared Zybertowicz on the radio. In turn, the minister of science, Jarosław Gowin, saw the discovery of "Kiszczak’s cupboard" as proof of the existence "of powerful pressure groups comprising personnel from the old system and part of the anti-communist elite who had been incorporated and had entered into a political and business symbiosis with former secret service circles".[1]

Essentially, the overwhelming majority of comments were based on conjecture rather than facts. Zealous exposés took the place of evidence, and the number of files multiplied visibly: two suddenly ballooned into thousands. Right-wing journalists argued that, since Kiszczak had hidden Wałęsa’s documents, the rest of the secret archives must have been concealed somewhere else. And they had to contain an immeasurable wealth of leverage, by means of which the “post-communist układ” was believed to be controlling politics in the country.

The entire "Kiszczak’s cupboard" affair coincides with the grand "historical policy" offensive proclaimed by PiS. From the outset, the view of history promoted by the party in power ("the patriotic narrative") has been a key point on its agenda, and it does not hide its intention to manage historical remembrance in the same way that it runs the country. Jarosław Kaczyński’s group has recently announced a new draft law concerning the Institute of National Remembrance, which will significantly expand its purview. Commentators are mostly mentioning Cenckiewicz as a likely candidate to become the INR’s new chairman. The historian has already made it clear on Facebook that it will be a personal priority for him to "reveal the inside story behind the economic and political transition [of 1989], after 16 years of neglect and helplessness [n.b. the INR was created in 2000]". Cenckiewicz has also declared his support for a full-scale campaign to seek the missing documents, as well as mass searches of the homes of former Ministry of Internal Affairs officials and Polish Communist Party politicians.

Translated by Mark Bence

Piotr Osęka: The Bolek Affair: Or, Kiszczak’s Cupboard and the Meaning of History. In: Cultures of History Forum (24.05.2016), DOI: 10.25626/0051.

Copyright (c) 2016 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

Lidia Zessin-Jurek · 20.04.2023

A History that Connects and Divides: Ukrainian Refugees and Poland in the Face of Russia’s War

Read more

Lidia Zessin-Jurek · 20.12.2021

Trapped in No Man’s Land: Comparing Refugee Crises in the Past and Present

Read more

Interview · 08.03.2021

A Ruling Against Survivors – Aleksandra Gliszczyńska-Grabias about the Trial of Two Polish Holocaust...

Read more

Lidia Zessin-Jurek · 03.09.2019

Hide and Seek with History – Holocaust Teaching at Polish Schools

Read more

Maciej Czerwiński · 11.04.2019

Architecture in the Service of the Nation: The Exhibition ‘Architecture of Independence in Central E...

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).