11. Apr 2019 - DOI 10.25626/0097

Maciej Czerwinski is Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures at Jagiellonian University in Kraków. His work is focused on South Slavic languages, literatures and cultures of the twentieth century in semiotic, discursive and historical perspective. He was a research fellow at Yale University (2003) and at the Imre Kertesz Kolleg in Jena (2015). He has authored numerous publications, including several books and edited volumes as well as literary criticism and essays on Balkan affairs. He also co-authored an exhibition on Ivan Meštrović at the International Cultural Centre in Krakow in 2017.

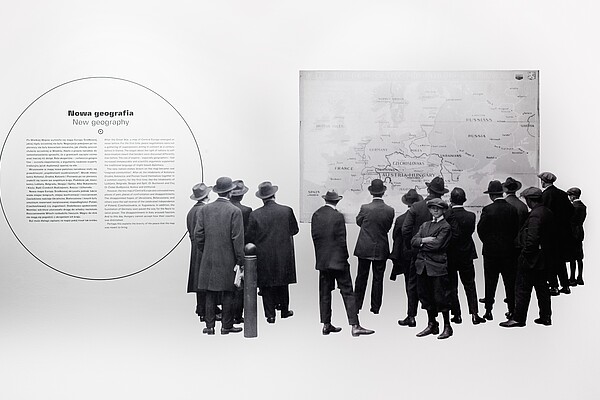

How should we understand the processes that governed architecture in the inter-war period? Nothing could be easier: all one needs to do is simply to follow Roland Barthes’s suggestions and narrate a short story about them. This is the path chosen by the authors of the Architecture of Independence in Central Europe exhibition, held at the International Cultural Centre Gallery (Międzynarodowe Centrum Kultury, MCK) in Kraków between 9 October 2018 and 10 February 2019.[1] They attempt to recount, and thus to understand, the processes governing architectural and urban planning policy in the inter-war period. Although the exhibition is part of the ‘Independence’ programme – a national programme which aims to commemorate the rebirth of the Polish state in 1918 – the authors decided to broaden the context to include all the countries of Central Europe. This approach has its undoubted merits, the most important of which is that it allows local phenomena to be seen against the background of the general trends that characterised the era. At the same time, it allows those local phenomena to elicit national varieties. The exhibition clearly shows that throughout the region – from Estonia to Yugoslavia, from the Soviet Union to Germany – a certain common language of architecture was dominant, even if it was based on a range of motivations and even if different circumstances preceded its creation. As in music, what we are dealing with here are variations – the presence of certain fixed motifs in diverse settings.

The exhibition may be regarded as the kind of inquiry that meets everyone’s expectations, both lay persons and experts. It is dominated by photographs, sketches, designs, and mock-ups – in a word, everything that makes it easier to explain, in comprehensible language, the way in which cultural landscape is designed. Fortunately, in keeping with the MCK’s approach, the authors eschew the over-use of audio-visual technology, so pervasive in galleries and museums nowadays. Traditional communication techniques, combined with a modern approach to the subject, are the undoubted advantages of this exhibition. Accompanying it is a bilingual album – a guide of sorts, but intended for the more advanced reader. The catalogue does not try to recreate the exhibition, as such catalogues normally do, but rather complements and enriches it.

Every era speaks in many languages simultaneously, although sometimes they convey convergent, if not identical meanings. One of these is the language of architecture. Construction is not only functional art that seeks to provide people with a roof over their head; it is also a method by which cultural elites communicate with society, rulers communicate with the ruled. Studying old architectural forms – urban and rural, modest and monumental, fortified and residential – makes it possible not only to investigate the zeitgeist of an era, to understand its turning-points and crises, its ambivalences and discontinuities, but also to grasp the dominant language of power. For the building of edifices also means the building of a collective identity; in the inter-war period, this identity was predominantly national. The metaphorical relationship between construction and the nation is reflected in common expressions such as ‘nation-building’. The nation is treated as a kind of edifice that needs to be built, and every effort must be made to ensure that it is solid, thus to ensure that it persists. The rhetoric of the nation clearly invokes Christ’s house on the rock from the Sermon on the Mount (Gospel of St Matthew).

After the end of the Great War, when suddenly – and probably unexpectedly – new countries appeared on the map of Central Europe, architecture was harnessed to a policy which sought to articulate their strength and postulated national unity. This applied to all the new states – those that fabricated their antiquity (Romania), those that excavated it from centuries of oblivion, creating hybrid constructs (Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia), and those that transformed it to suit the exigencies of the moment (Germany, Poland, Hungary). In all these cases, the motivation was the same: to express, or rather project, ideas about the greatness of a nation and its venerable age, but also its vitality. Such tendencies were not, of course, typical of this region only; indeed, their prototypes emerged in other parts of the continent. In searching for the connections and affinities between them, one of the curators, Żanna Komar, looks to Paris and Rome as well as the Soviet Union. All these places shared the same desire:

In the 1920s and 1930s many Central European capitals introduced architectural theatres of power modelled on ancient Roman fora. In urban plans, one can easily distinguish shared features, or rather a common pattern: huge arteries, monotonous colonnades, central symmetry, vastness, scale, and power.[2]

A similar form of expression was used by everyone – both the winners of the Great War (Poland, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia) and its losers (Germany, Hungary). This is the first and most important lesson of the Kraków exhibition.

During the inter-war period, mass graves and mausoleums were worshipped with special reverence; they spoke the same language, almost ossified in its sacredness. Similar in their eloquence were the altars of the fatherland created in the then Prussian town of Tannenberg (the Tannenberg Memorial was meant to commemorate not just the victory over the Russian army in 1914, but was also seen as Germanic revenge for the defeat of the Teutonic Knights at nearby Grunwald in the Middle Ages); in the then Polish city of Lwów (Cemetery of the Defenders of Lwów); in Mărăşeşti in Romania and in Avala near Belgrade (Monument to the Unknown Soldier); and in Bradlo in Slovakia (Monument to General Milan Rastislav Štefánik).

All these buildings are monumental and explicit in their pathos, but they have something else in common – an archaic style or, at best, unmistakable references to times past. The older a nation’s origins, the more eminent its role in the modern world appears. No wonder, then, that the ‘younger’ nations readily embraced old architectural forms. It was felt that this was the only way they could free themselves from historical lethargy and overwhelmingly archaic modes of existence. In the case of Romania, where on the fields of Mărăşeşti it was decided to allude to the Roman Mausoleum of Augustus, one more innovation was introduced. Only their elder brothers – the Romans – could testify to the Romanians’ longue durée, to their antiquity. And so they did! In Cluj – an important city for the Hungarians, which after the Treaty of Trianon found itself within the borders of Romania – the Capitoline Wolf (a sculpture depicting a she-wolf suckling Romulus and Remus, the mythical founders of Rome) was unveiled in 1921. It was a symbol of Roman heritage (the ancient province of Dacia). The authorities intended it to act as a counterbalance to the traditions of Hungarian Transylvania, symbolised by the medieval market square. The antiquity of the Romanian people was thus legitimised by Rome itself. On the plinth of the monument, the inscription clearly reads: “ALLA CITTÀ DI CLVJ, ROMA MADRE, MCMXXI” (To the City of Cluj, Mother Rome, 1921). One can imagine that Romulus is the symbol of Italy, and Remus – of Romania. The she-wolf is, of course, the mother of both brothers, so it no wonder that she had to appear on Romanian soil. This civilised ancestry was meant to overshadow the ‘barely medieval’ legacy of the Hungarians, descendants of the barbarian Huns.

What in Romania was seen as confirmation of the country’s inclusion in the heritage of Western civilisation, in neighbouring Yugoslavia, and more specifically in Croatian Dalmatia, would have been treated as an insult bordering on betrayal. Dalmatia, which was more firmly rooted in the Roman Empire than Dacia, and in its cultural landscape preserved far more traces of that presence, was highly aware of its distinctiveness. Literature written in Croatian, which emerged in the Middle Ages, and the Slavonic liturgical rite, which was an original contribution to the culture of the West, instilled in the Croats a strong sense of agency. Therefore, although they had undoubtedly inherited the Roman/Romanesque tradition, they did not need any evidence to prove this obvious fact. Not only were no she-wolves brought to Dalmatia, but attempts were even made to weaken the existing Roman legacy. On the central square (Peristyle) of Diocletian’s Palace in Split, a huge sculpture by Ivan Meštrović depicting Bishop Gregory of Nin was erected. Although, in truth, Gregory did not fight for the rights of the Slavonic language, as was mistakenly thought, he nevertheless represented, in mythical belief, resistance to Rome and to Italianisation. To this day, neither she-wolves from the Eternal City nor (especially) lions from the Republic of St. Mark are popular in Dalmatia; yet in Romania they are.

As documented in the exhibition, the very same Meštrović designed the Monument to the Unknown Soldier on Avala Hill near Belgrade. Here he used a different solution, intertwining an ancient form (the sarcophagus) and caryatids with native folklore, something he was obsessed with throughout his career. The caryatids are not dressed in antique costumes, but in local attire. They represent the Yugoslav regions, although not all of them and not on equal terms; it is an allegorical ‘delegation’. Without batting an eyelid, these peasant women from Bosnia, Croatia, and Serbia carry on their heads the burden of Yugoslav unity. Incidentally, when work on the monument was under way, Yugoslavia was already being shaken to its foundations. It was the same story in many other European countries. The nation-states that had been built with such toil would soon disintegrate in the clash between two cruel totalitarian regimes.

The exhibition also shows how, after the First World War, monuments were removed from public spaces in order to obliterate all traces of ‘foreign’ rule. This was the case in all the countries of the region. In Warsaw, the Cathedral of St Alexander Nevsky, a symbol of enslavement, Russification and Byzantinisation, was dismantled. Soon Sergei Eisenstein would use this Orthodox saint to rally the descendants of Rus’ against the Teutonic Knights in their modern incarnation – Nazi Germany. The film was not only anti-German, but also overtly anti-Catholic, and by showing the eternal struggle between Rus’ and the Teutons, it neatly camouflaged Stalin’s alliance with Hitler.

Once the visitor has understood how the authors of the exhibition treat the language of architecture, he/she arrives at the inevitable: conflict. The nation-states were not, after all, created to the satisfaction of all concerned. When designing these new political entities, decision-makers resorted not only to historical arguments, but also to maps. Hundreds of them were created. Cartography, often underpinned by racial theories, became an important means of refuting an opponent’s arguments.[3]

Correlations were sought between the ‘ethnopsychology’ of nations and the environments in which they lived. Allied commissions flooded the conflict regions, and yet the end of the Great War did not signal the end of the fighting. The Polish-Soviet war as well as territorial disputes between Italy and Yugoslavia, Poland and Czechoslovakia, and Poland and Germany, would leave their mark on the atmosphere of the entire inter-war period. Eventually they would become one of the reasons for the outbreak of the Second World War: the alliance with Hitler gave Soviets, Italians, Hungarians and Bulgarians a convenient excuse to redraw ‘unjust’ borders. This entailed the return of ‘indigenous’ territories, temporarily occupied by neighbouring states, to their rightful home. Once again, historians and geographers entered the fray. They sought to prove that previous findings were worthless. New maps were accordingly created.

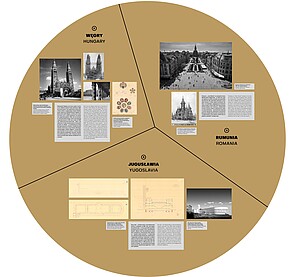

In order to explore the nature of the inter-war conflicts on the borderlands, the authors of the exhibition decided to present the issue in visual form. This proved to be the right decision, for it is an excellent way of helping visitors to understand the exhibition. Conflict-ridden territories are presented on boards in the form of a circle, which is divided into three parts by three lines (radii) drawn from its centre (see picture). This tripoint presents in graphical form the meeting of three countries and three historical imaginations in single place. Three such places are selected for analysis: the Polish-Czechoslovak-Romanian (Użhorod, Pop Ivan, Chernivtsi), Polish-Czechoslovak-German (Upper Silesia), and Hungarian-Yugoslav-Romanian (Szeged, Novi Sad, Timișoara) tripoints. Buildings would be erected at tripoints to mark the respective territories with a particular presence. This was meant to constitute proof that lands concerned belonged to this or that country – like a cadastral map from the land registry.

When organising the symbolic space, various idioms were used that could be presented as native. In all the tripoints, each party had good reasons to prove its ownership of the lands concerned. In one of them, Yugoslavia and Romania wanted to do so because they had gained the lands; Hungary because it had lost them. The Hungarian authorities commissioned a huge eclectic cathedral in Szeged that clearly referred to historical styles; its walls were decorated with murals depicting the history of Hungary, inscribing the Lands of the Crown of St Stephen in an almost divine plan of creation. Meanwhile, in Timişoara, which became part of Romania, an equally eclectic Orthodox church was built (1936-1941, Ioan Traianescu). The idea was to introduce into this Habsburg (Catholic!) universe at least a small element of Orthodox culture. According to the authors of the exhibition, the ‘painted monasteries’ of Bucovina, the cradle of Romanian statehood, were the model for this ‘Byzantinism’. And finally there was Novi Sad, which after the war was given to Serbia (Yugoslavia). In contrast to Szeged and Timişoara, the style used there was extremely modern. In 1935-1939, the modernist Banovina Palace (designed by Dragiša Brašovan), which is still used by the Provincial Government, was erected in the ‘Serbian Athens’. It comprises almost 600 rooms with a total area of 5 700 m2. For the authors of the exhibition, this is undoubted proof that “this ‘ship on the Danube’ was a showcase presenting the modernity of Yugoslavia to its Hungarian and Romanian neighbours.” Whereas the Hungarians and Romanians invoked antiquity, the Serbs appealed to freshness and vitality (this was not, however, a reflection of the ideas of the “Barbarogenius” Ljubomir Micić, because the latter’s project, although declaratively anarchist, was anchored in Orthodox tradition).

The example of Novi Sad clearly shows that not just stylisations of antiquity, but also a style that was essentially international, could be used to articulate national character. One of the exhibition rooms is dedicated to the presence of modernist idioms in Central Europe of the inter-war period. Modernisation was translated into major social housing projects, over which the spirit of Le Corbusier and the Bauhaus hovered. The enormous need to absorb the rural population into cities led, after the war, to the large-scale creation of extremely functional cooperative apartments. However, in this area too, differences became apparent. Michał Wiśniewski notes that although Central Europe espoused modernist trends, the extent to which this idiom took root was different in Poland compared to Czechoslovakia, for instance. In Wiśniewski’s view, this was due to the inheritance of certain political inclinations and intuitions.

The state of Czechoslovakia, which was the result of a pragmatic decision by Czechs and Slovaks made against Germany and Hungary (the two powers that had dominated them for centuries), had to invent a common and unifying cultural code. Unlike Poland, which for a long time had been building its architectural identity around the history of the nobility and through attempts to merge the old with the new, Czechoslovakia turned decisively toward modernity.[4]

The author quickly adds, however, that this cannot be treated in black-and-white terms, but rather in terms of the extent to which modernism was assimilated and absorbed. After all, in Poland too, experts polemicized about the new architecture, which had its domestic proponents. Gdynia, in turn, can be seen as a ‘battleground’ between supporters of the old and the new. Although the port city makes only a cursory appearance at the exhibition, it is given more space in the catalogue. Andrzej Szczerski notes there that Poland’s “window to the world” bore witness to a rivalry between two traditional idioms – modernism and the so-called “manor style”.[5] In time, the former gained a dominant position and determined the face of the city. Thus, Gdynia – and to a lesser extent the districts and quarters of some cities (Warsaw, Kraków) – stood out from the rest of Poland. The authors of the exhibition reveal that modernisation projects did not bypass the countryside. In Lisków in the Wielkopolskie region, a model cooperative village was established, which not only led the way architecturally but also significantly improved the inhabitants’ standard of living (health care, education).[6]

The exhibition also shows how ascetic modernism gave rise to its elite variety, preserved to this day in some parts of Central Europe, for instance in Brno (Ludwig van der Rohe’s Tugendhat Villa).

In all European countries, not only those created after the fall of the great empires, a cult of the body reigned. The apotheosis of youth and strength, coupled with the promotion of hygiene, were aimed at integrating humankind into the new world (the mechanisms behind the creation of this model are discussed in the catalogue by Natalia Żak). Architecture became a medium for communicating these trends. Leisure centres, spas, sports halls, and stadiums sprang up like mushrooms after rain. Sport and tourism – supported by various youth organisations and hiking associations (scouting, the Sokol movement) – were seen as an element of patriotic education. What this entailed – as it might be described in today’s language – was the ‘social inclusion’ of the lower classes, for whom national consciousness was as exotic as Newtonian mechanics. Last year, also as part of the centenary of Polish independence celebrations, an excellent exhibition entitled “The Future Will Be Different” was organised at the Zachęta Gallery in Warsaw. It showed how attempts were made to overcome the divisions left over from the era of Partitions and to include all social strata in the bloodstream of the modern nation. Modernisation projects, including architectural ones, also tried to eliminate existing divisions. The nation was to be cohesive.

The creation of new buildings and the demolition of others was mentioned earlier. As shown at the Kraków exhibition, there were also projects to redevelop existing urban areas. These usually involved altering places considered important for the emerging national identity – castles, parliaments, and the main arteries of cities. Although the intentions of the authors of such projects were generally similar, the situation in Central Europe was far from uniform. One of the exhibition commentaries refers to this directly:

In the case of cities such as Prague or Budapest, which experienced rapid development in the 19th century, it was enough to shift the emphasis and alter the expression of certain public spaces. The situation was different in provincial cities hitherto devoid of significance. Tallinn and Kaunas had to be reinvented; their spaces had to acquire drama and a symbolic dimension. To this end, monumental parliament buildings, ministries, churches, and cultural institutions were eagerly raised.

Both these phenomena are confronted at the exhibition. In the capital of Czechoslovakia, for example, the reconstruction of Prague Castle was not meant to intervene in its fabric, but merely to supplement it with new content. In Tallinn and Kaunas – essentially provincial towns, but which now became the capitals of the new states of Estonia and Lithuania – the changes were more profound. The exhibition presents many of the projects carried out in Central European capitals, the most noteworthy among which were the National Assembly (Riigikogu) building in Tallinn, which combined expressionism with native folklore, and the extraordinarily eclectic, grand urban layout of Kaunas.[7] The reconstruction of the Hradčany, in turn, was probably the most successful project of this kind carried out in Central Europe. It was undertaken by the outstanding Slovenian architect Jože Plečnik, and his design – symbolising the triumph of the Czechoslovak nation – has been the subject of numerous studies.[8] It is a pity that when discussing the sadly never-to-be realised plan to reconstruct Warsaw’s Mokotów district, the authors of the exhibition fail to mention that the person closest to winning the competition to design Piłsudski Square, together with a triumphal arch and an equestrian status of the marshal – was none other than Ivan Meštrović. The Second World War put paid to those plans, and the bold design, which included a several-kilometre-long avenue and Temple of Divine Providence – was never implemented.[9] But, in any case, Plečnik’s work in Prague and the great interest shown in Meštrović in Warsaw and Bucharest testify to the strong ties connecting the whole of Central Europe at that time. What is more, they show that the era had its own wandering prophets.

The exhibition closes with a presentation of the would-be capitals of countries that became republics of the Soviet empire, which emerged from the ruins of the Great War. In spite of these inauspicious beginnings, the first capital of Soviet Ukraine, Kharkov, and Belarusian Minsk, were also consumed by modernisation fever. Bohdan Cherkes writes about the former city in the context of the modernisation of Kiev. The final articles in the catalogue are devoted to urbanisation processes and their ideology motivations in various regions of Central Europe – in the Baltic States (Mart Kalm), in Czechoslovakia (Henrieta Moravčiková), and in Yugoslavia (Aleksandar Kadijević).

Although the Kraków exhibition does not say so explicitly, it should be pointed out that despite the recent memory of the Great War, with all its horrors, efforts at construction and reconstruction were greeted with genuine enthusiasm by the region’s inhabitants. They gradually became citizens of new countries, and instead of feeling like peasants or proletarians, they could now be Poles, Czechs or Hungarians. Monumental architecture, hitherto the exclusive preserve of the wealthy, suddenly became a common good. The emergence of the nation was accompanied by greater egalitarianism, because in Europe the national idea was a sine qua non of democracy. Architecture, along with other languages of art in the inter-war period, triumphantly announced that citizens equal before the law had vanquished the class society. This was one of the consequences of the Great War, which put the seal on the changes taking place in Europe. These included a new definition of sovereignty, which was no longer equated with the dynastic inheritance of land but with the rights of the nation.

And one more thing, in passing: in order to make the architectural designs understandable, attempts were made to convince members of the community that they were the descendants, even if only symbolically, of the heroes commemorated in mass graves. Every German, Slovak or Serb could feel that his father, or even his great-great-grandfather, lay in Tannenberg, Bradle or Avala. Making a member of the national community sensitive to the process of implementing a great architectural project meant involving him in the act of creation. He was treated as a subcontractor or at least as a witness to that process. These imaginary subcontractors were, for instance, citizens of the newly-independent Poland who bought bricks to rebuild Kraków’s Wawel Castle – the national pantheon (they even had their names inscribed on the bricks). Witnesses, in turn, were those who participated in putting buildings to use. This was usually accompanied by a ritual that bordered on the theatrical. Was this the birth of performance art?

The exhibition raises a number of issues – those that are addressed and those that the visitor is left to ponder. The authors cannot be accused of selectivity, because the exhibition was conceived as a problem-oriented monograph and not as an encyclopaedia of knowledge about inter-war architecture. Whereas an encyclopaedia has alphabetically arranged entries, a monograph is characterised by issues organised in line with the adopted logic of argumentation. It is a pity, however, that the content of the exhibition was not represented in the catalogue. Although the articles therein explain a lot about the phenomena of the era, the exhibition narrative itself – supplemented with pictures and commentaries – is an excellent example of how the role of architecture in pre-war Central Europe can be popularised.

Translated by Jasper Tilbury

Maciej Czerwiński: Architecture in the Service of the Nation: The Exhibition ‘Architecture of Independence in Central Europe’. In: Cultures of History Forum (11.04.2019), DOI: 10.25626/0097.

Copyright (c) 2019 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

Lidia Zessin-Jurek · 20.04.2023

A History that Connects and Divides: Ukrainian Refugees and Poland in the Face of Russia’s War

Read more

Lidia Zessin-Jurek · 20.12.2021

Trapped in No Man’s Land: Comparing Refugee Crises in the Past and Present

Read more

Interview · 08.03.2021

A Ruling Against Survivors – Aleksandra Gliszczyńska-Grabias about the Trial of Two Polish Holocaust...

Read more

Lidia Zessin-Jurek · 03.09.2019

Hide and Seek with History – Holocaust Teaching at Polish Schools

Read more

Marta Bucholc and Maciej Komornik · 19.02.2019

The Polish ‘Holocaust Law’ revisited: The Devastating Effects of Prejudice-Mongering

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).