20. Apr 2023 - DOI 10.25626/0145

Dr. Lidia Zessin-Jurek is a historian, memory researcher, press columnist (e.g. Gazeta Wyborcza, MicroMega) and a Poland expert in the ERC-Project "Unlikely refuge? Refugees and citizens in East-Central Europe in the 20th century" at the Masaryk Institute and Archives (MUA), Czech Academy of Sciences in Prague. She also works for the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure Project (EHRI) and for the European Commission (European Education and Culture Executive Agency, EACEA).

“I am proud to be the US ambassador to a humanitarian superpower,” said Mark Brzezinski in a 9 May 2022 at the University of Warsaw. In so doing, he wanted to applaud the role played by Polish society in the first year of Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine. Indeed, the widespread recognition received by Poles for their spontaneous and generous solidarity with Ukrainian refugees was an important source of motivation for their continued relief efforts.

“This is Poland, not Ukropol!” has become the slogan on the other side of this ‘Polish coin.’ More than a year after the mass exodus of mostly women and children from Ukraine began, and despite the continued sympathetic attitude among the majority of Poles, there are also signs of a growing resentment among some Poles toward their neighbours across the Eastern border. Behind these feelings is likely a sense of envy at the financial assistance provided to Ukrainian refugees in Poland, as well as controversies surrounding welfare spending, the cost of military support, and the impact of cheaper Ukrainian grain – sometimes accompanied by the claim that Ukrainians are not sufficiently grateful for the help provided. What has also increased in chants at demonstrations and in the media is the visibility of anti-refugee slogans relating to the turbulent Polish-Ukrainian past.

Ultra-right wing circles (still rather small in number but currently gaining in popularity) seek to fuel both economic and historical arguments against Polish solidarity with Ukrainian refugees. Their activities are embedded in a society with a strong sense of unrecognized historical victimization relating to the Second World War and the Communist regime. References to historical memory retain great political appeal, and memory remains an important tool for mobilization and the building of support. This article discusses how the reception of Ukrainian refugees has been affected by various Polish memory frames, and vice versa, how the war and the refugees from Ukraine have influenced collective remembrance in Poland.

The shock that a war was being waged anew in twenty-first century Europe, was a major catalyst for Poland’s almost unequivocal and extremely heartfelt initial humanitarian impulse. Refugees fleeing from a full-scale invasion of their country from the outside and an invasion that aimed to not only conquer their state, but also destroy their nation – is a situation that has been largely absent from Europe since the end of the Second World War. Yet it happened again, in 2022. The Russian attack on Ukraine in February 2022 was not unlike the Nazi-German attack on Poland in 1939, as both were preceded by the fact that neither country bowed to the demands of an aggressive neighbour. Both then and now, the aggressors portrayed the country they were invading as an ungovernable, failed and “temporary” state, incapable of protecting its citizens and minorities. However, while the Polish state in 1939 succumbed to combined German-Soviet aggression rather quickly, Ukraine has thus far managed to avoid a similar fate.

The historical analogy between 1939 and 2022 has been very present in the public discourse in Poland, becoming the primary argument for helping refugees – “as Poles sought refuge in other countries then, so do Ukrainians today.” Notably, what is at issue here is the very notion of refuge, and not the historical circumstances that most Poles fleeing from the Germans in 1939 sought refuge precisely in what is now Ukraine, a fact that has thus far escaped the Polish collective consciousness. Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy himself used the ‘1939-2022-analogy’ on 1 September 2022 in his address to the Poles, when he noted that “On the morning of 1 September 1939, bombs fell on Wieluń. On the morning of 24 February 2022, this was repeated in Ukraine.”[1] Among the Polish elite, the dominant wish seems to be for Ukraine, unlike Poland in 1939, to receive rapid and substantial support from ‘the West’, including its closest and largest Western neighbours – Poland and Germany. And indeed, along with support in the form of military equipment, emergency assistance has been provided for crisis relocation within the war-torn country and for those crossing the border.[2]

This immediate and generous aid response was also due to the fact that Poles (and Europeans more generally) recognized themselves in the Ukrainians, more so than in the victims of other recent wars, such as in Syria or Yemen. ‘Racial’ considerations and the Polish government’s previous anti-immigrant discourse vis à vis refugees crossing the Polish-Belarusian border[3] play an important role here. Welcoming women and children from Ukraine, rather than the largely male refugees coming from non-European countries (the refugee profile is different due to the differing context of each conflict), was taken as a given – not only within generally aid-oriented milieus. Groups that had previously opposed taking in refugees now supported the Ukrainians by reiterating their earlier arguments about ostensibly “real” (i.e., vulnerable) versus “fake” (i.e., economic migrants) refugees.[4]

The fact that Ukrainian refugees were fleeing a historically-speaking “common enemy”—Russia—further expanded the scope of solidarity and understanding for Ukraine, as the reality of a war taking place just across the Polish border awakened the familiar fear of Russian imperialism in Poland. In addition, the fact that Ukrainian soldiers are forced to face Putin’s aggression alone has also fuelled Polish support for supplying Ukrainians with as many NATO weapons as possible.

This theme – fighting the common enemy of Russian neo-imperialism – continues to permeate Polish public debate on Ukraine, Ukrainian refugees and the common Polish-Ukrainian past. President Zelenskyy has been instrumental in evoking earlier Polish-Ukrainian alliances against the Russians using various anniversary celebrations in Poland. He would recall the united front between the two peoples not only on the anniversary of the 1939 war, but also much earlier events, such as the 160th anniversary of the January Uprising in 1863 (Poles against the Tsar), a more controversial historical memory. Indeed, the reference to the 1863 Uprising was met with some hesitation among Polish right-wing media outlets, who believe the narrative of a united Polish-Ukrainian front during the uprising to be a historical falsification intended to bolster the current Polish-Ukrainian alliance, and argue that the Ukrainian population in no way supported the Polish nobility’s aspirations for independence during that period.[5]

Half a century later, in 1920, Poles and Ukrainians did unite against the Russians in the aftermath of the Bolshevik Revolution, when the Polish state was being rebuilt and the foundations of Ukrainian statehood were being laid. After 1989, Polish mainstream media has regularly marked the anniversary of Józef Piłsudski’s 1920 alliance with Symon Petliura against the Bolsheviks, often with a sense of betrayal on the Polish side: By March 1921, Poland had signed the Riga peace treaty with Soviet Russia, disregarding Ukrainian interests.[6] The current war has further emphasised the themes of this (failed) alliance. According to various historians, “bringing back the memory of Symon Petliura and the joint fight against the Russian empire has never been more important.”[7] The experiences of 1920-1921 and of 1939 emerged in the media as a further reason for Poland to feel an obligation to support Ukraine. Often quoted in this context are the words of Józef Piłsudski: “The blood that we shed together, and our soldiers’ graves laid the cornerstone for mutual understanding and the prosperity of both nations.”[8]

Yet these references to 1921 are also frequently accompanied by another Piłsudski quotation, uttered after Ukraine fell into Russian hands: “My apologies, gentlemen, it was not meant to be like this.” Indeed, the failed Polish-Ukrainian alliance against the Bolsheviks is just one of many thorny issues in a long, difficult relationship between the two countries. On the Polish side (the focus of this article), the short-lived alliance between Poland and Ukraine is not widely known; although briefly introduced at school, the subject remains largely confined to expert debates in political magazines. A similar thing can be said about the conflict between the two neighbours that goes back to the Polish latifundia (that is, extensive pieces of privately owned lands) on Ukrainian (Ruthenian) land in the seventeenth century, during which feudal exploitation of local populations and the disregard for the Cossacks’ emancipatory aspirations led to uprisings against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In 1667, the truce of Andrusovo settled these unrests and resulted in half of the Ruthenian land falling under the control of the Russian empire. In terms of its aftermath (the betrayal of Ukrainian nationalist aspirations), the 1667 truce is often compared to the 1921 Peace of Riga.

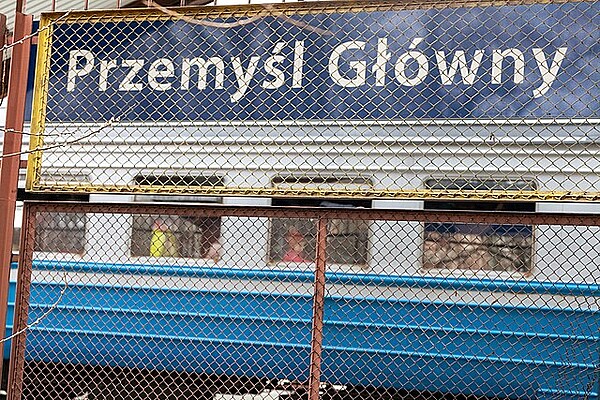

The Peace of Riga was preceded not only by a Polish-Ukrainian alliance, but also by a bloody border standoff between Poland and Ukraine from 1918 to 1919 over the city of Lviv/Lwów. The city eventually became part of the Second Polish Republic, along with Volhynia and Podolia. As a symbol of Polish (not Ukrainian) sacrifice, the cemetery of the so-called ‘Eaglets of Lwów’ is a lieu de mémoire deeply imprinted on Polish remembrance culture. The Eaglets were young Polish volunteers fighting for Lwów, first against the Ukrainians (1918) and then the Russians (1920). The bilateral feud over the memorial site, in particular the lion statues in the centre of the cemetery, which were perceived by many Ukrainians as “symbolising the Polish occupation of Lviv” and were removed in 1971, goes way back to the early 1990s. In 2015, they were returned to the cemetery amid much controversy and remained covered by clapboards. It is no coincidence that they were finally unveiled shortly after the Russian invasion, in May 2022. The current mayor of Lviv, Andryi Sadovyi, referred to this event as an important “step towards a final act of forgiving one another for all the injustice done in the past.”[9] In January 2023, the presidents of both countries, Volodymyr Zelenskyy and Andrzej Duda, met at the cemetery to affirm the strength of the Polish-Ukrainian alliance. During this visit, they signed a declaration against the “tyranny from the East” together with Lithuanian President Gitanas Nausėda.

Nevertheless, this important breakthrough in the perception and commemoration of 1918-1921 has not resolved all issues. By 1939, Lviv/Lwów and what is now Western Ukraine had been part of Poland for two decades, over the course of which Poland gradually intensified its efforts to colonize it, in line with its increasingly nationalist policies. The government promoted Polish agricultural settlement in regions that were populated mostly by Ukrainians (and Jews in the shtetls), while Ukrainian aspirations for cultural and, even more importantly, political autonomy were dismissed. In 1943, growing tensions – already exacerbated by a centuries-old social hierarchy between the Polish nobility and Ukrainian peasants – erupted, as tens of thousands of ethnic Poles in Volhynia were killed by Ukrainian nationalists and thousands of Ukrainians perished in reprisals. Just prior to these events, Germans had liquidated Jewish ghettoes and exterminated Jews from local towns, which provided an additional context to those seemingly unimaginable crimes amongst neighbours. Of all the events in a long history of Polish-Ukrainian neighbourly relations, the Volhynian tragedy has been most often used, particularly by the contemporary Polish far right, as an argument against helping Ukrainian refugees. The UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army) is brought up as the main culprit, leading contemporary Ukrainians to be dubbed UPAinians or Banderovites (referring to Stepan Bandera, the leader of the pre-war Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists, OUN).[10] In this context, Ukrainian refugees are burdened with full responsibility for their ancestors’ sins, while Poland is believed to be turning into some kind of a “Banderland”.[11]

Historical Claims and References in Contemporary Anti-Refugee Campaigns

Both Polish liberal (de facto oppositional) and state-owned (read: government-controlled) media outlets have continued to sympathise with the plight of Ukrainian refugees – the only thing that both political camps in a deeply polarised Polish political landscape continue to have in common. However, a growing number of Poles have begun to identify Ukrainians as the heirs of the Volhynian massacre, framing them as a potential threat to the Polish nation. This is likely the result of an increasingly successful campaign by the radical right-wing political party Confederation Liberty and Independence (Konfederacja Wolność i Niepodległość), whose supporters include xenophobic enthusiasts of conspiracy theories, including anti-vaxxers, Eurosceptics and antisemites. From their perspective, Poland is at risk of becoming a ‘Ukropolin’ (a port-manteau of Ukraine and Polin, a Hebrew word for Poland), and Ukrainians are “Nazis” and “invaders” (nachodźcy) rather than “refugees” (uchodźcy), engaged in “resettlement” instead of receiving “refugee aid” in response to a “so-called” war.[12] Mirroring the Russian disinformation strategy, this rhetoric against Ukrainians in Poland appeared well before February 2022, but truly gained momentum only after the full-scale invasion.[13] In November 2022, polling experts concluded that the majority of Poles were not susceptible to this fake news.[14] Six months later, however, a worrying trend became apparent: public exposure to anti-refugee content had increased, while resilience to it had diminished.[15] This trend was confirmed by a surge in the number of anti-Ukrainian incidents, in the form of both verbal and physical violence against refugees.

One widely reported incident was the disruption of two literary events in 2022 in Kraków and Poznań, during which one guest, the renowned Ukrainian novelist Oksana Zabuzhko, was heckled by members of the audience, who wanted her to apologize for the Volhynian tragedy.[16] Crimes against civilians (past or present) represent an emotionally charged issue and can easily be used as an instrument to drive a wedge between Poles and Ukrainians. Indeed, the Volhynian tragedy has often caused diplomatic turmoil between the two countries. In 2017-18, the Polish Sejm passed an infamous amendment to the Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) law criminalizing “attribution of the responsibility for the Holocaust crimes” to the Polish nation. The amendment also included a mention of the “crimes of Ukrainian nationalists”, the denial of which would be punishable by up to three years in prison.[17] After the outbreak of the full-scale Russian war, Confederation MPs suggested yet more legislation on memory: during a press conference in the Sejm they made the proposal that all Ukrainian refugees in Poland be obliged to sign a declaration – dubbed the “anti-Bandera liability pledge” – that they were aware of the crimes in Volhynia, condemned the activities of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army and would promote knowledge on the subject upon their return to Ukraine.

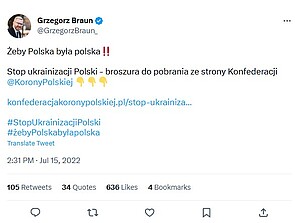

An increasing number of social media posts and public speeches have begun to incorporate references, often sensational in tone, to the events of Volhynia in order to spark discord between Poles and the Ukrainian refugees. Since connecting contemporary (mainly female) Ukrainian refugees with a historical (masculinized) partisan threat can prove difficult, one of Confederation’s chairmen, Grzegorz Braun, has chosen a different tack, regularly spreading the conspiracy theory of a so-called ukrainization of Poland (as exemplified by the slogan shared on Twitter “No to the replacement of Poland’s ethnic structure”).

Each of these narratives is reminiscent of the rhetoric directed against refugees from outside of Europe. Unlike in the case of anti-Ukrainian slogans, the anti-refugee rhetoric of earlier years – which focused on immigrants from non-European countries who try to enter Poland via the Belarusian border – was widely popularised by the government and government-controlled media outlets. The emphasis was usually placed on stoking fears of “Islamism”, which was directly connected to male migrants, and propagated the belief that the indigenous population (of Poland or Europe in general) is gradually being replaced by newcomers with an alien culture (the “Islamization” discourse resembles “ukrainization” discourse).

The very same government is now trying to mollify social concerns related to the high number of Ukrainian refugees, by calling for patience and pushing aside attempts to use historical memory to blackmail Ukraine.[18] At the same time, to avoid falling out of favour with its radical electorate, the PiS-government has reassured its supporters that talks with President Zelenskyy on the Volhynian tragedy continue to deliver positive outcomes, for example in form of (another) breakthrough decision in 2022 by the Ukrainian authorities to allow for the exhumation and proper reburial of Polish victims of the massacre. Polish politicians continue to emphasize that by opening its doors to refugees from Ukraine, Poland had proven itself to be a truly loyal friend, regardless of the weight of history, which will convince Ukrainians in Poland and those in Ukraine to adopt a more sensitive approach to Polish “historical wounds”. In a speech on 22 July 2022, Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki emphasized that “Russia’s war offers an opportunity to finally achieve reconciliation between Ukraine and Poland over the massacre of Poles by Ukrainian nationalists in the Second World War.”

The liberal political wing in Poland has not formulated any expectations towards Ukrainians with regard to history or memory. However, the most renowned expert on the so-called Volhynian massacre, Grzegorz Motyka, has argued that the upcoming eightieth anniversary of the tragic events of 1943 (traditionally commemorated in July) might become a genuine breakthrough in Polish-Ukrainian discussions about the past. In his view, the most important thing is to properly commemorate the victims, which has been made possible by the recent Ukrainian agreement to exhume and appropriately bury the victims.[19] According to Ukrainian intellectuals in the Polish media such as Jaroslav Hrycak, a complete reconciliation that also encompasses the figure of Stepan Bandera, is yet unlikely. That said, many in Germany and France do not see eye to eye about some of the more contentious chapters in their shared history, yet the imperfect consensus between these two nations and their respect for each other nonetheless provided the foundation for European political integration. Today, mutual respect between Ukraine and Poland could form the foundation for a historic enlargement of the EU further east.[20]

Against this backdrop of reconciliatory voices seeking to establish some sort of “hierarchy of antagonisms” – wherein the antagonism toward Russia is greater than mutual Polish-Ukrainian antagonisms, Polish right-wing historians have also become vocal about their expectations of an apology from the Ukrainians, in line with the radical political right. Historian Jan Żaryn offers a rather interesting reference point here, as he has demanded Ukrainian apologies to the Poles (for Volhynia), while simultaneously making reference to the role Ukrainians played in the Holocaust in formerly Polish regions: “but this [the collaboration during the Holocaust] is not our problem; sooner or later, it will have to be handled by the Ukrainian authorities as an issue affecting Israeli-Ukrainian relations.”[21] One can understand that Żaryn does not want to usurp all the entitlement to Ukrainian apologies, but with this added remark he achieves something else: By expecting Ukrainians to apologize solely to ethnic Poles, while ignoring other citizens of the Second Polish Republic (the Jews), he is able to rhetorically push Polish Jews to the margins of any Polish culture of remembrance.

Beyond the comments of certain right-wing Polish historians, the genocide perpetrated against the Jews during the Second World War is yet another topic from the past often referenced in the context of the current war. Politicians from the ruling party in Poland speak with conviction of a “Russian genocide of Ukrainians” in Bucha, near Kiev.[22] While liberal media outlets express a similar degree of concern for the horrific crimes committed there, they also reflect on the accuracy of the term ‘genocide’ in this context.[23] Adopted from the culture of the Holocaust remembrance, the slogan “never again” continues to resonate with both groups, although its actual value has increasingly been questioned. By drawing an analogy between the Russian crimes against Ukrainian civilians and the German crimes against Jews, broadly perceived as history’s gravest crime, the obligation to help Ukrainian refugees becomes a matter of the utmost urgency. In parallel, the historical complicity of Ukrainians in the murder of the Jews is absent from both governmental and liberal discourses, since the Polish government has long avoided addressing the “domestic” issue of the role of Polish citizens in denouncing and killing Jews, much less expect the same from Ukrainians.

If we were to extend the scope of our analysis to look at the memory culture prevalent in the country bearing the main responsibility for these crimes – Germany – a different picture emerges. The German public has been more susceptible to the Russian propaganda that portrays contemporary Ukrainians as Nazis or fascists. One of the reasons is that (unlike in Poland) the failure to bring Nazi collaborators to justice is a matter of importance to the current German culture of remembrance. In addition, during the last fifty years, Germans have invested more heavily in building positive relations with Russia than with Ukraine. In short, virtually every country has its own unique remembrance culture connected to Russia – though often a bit less so to Ukraine. With the arrival of Ukrainian refugees, each must try to figure out a new way to engage with both states, navigating between Ukrainian war rhetoric and Russian disinformation strategies. The former is usually developed on an ad hoc basis and designed to generate the highest possible level of empathy and support; the latter resorts to traditional and proven Soviet methods (i.e., the war is an act of “defence”, not an attack). Thus far, the diversity of attitudes toward Russia and Ukraine has not changed the overall positive reception of Ukrainian refugees in the majority of European countries.

Within this broader landscape, Ukraine and Poland “share a history” on an unparalleled scale in Europe, including contentious and unresolved issues. Today, the historical connections between Poles and Ukrainians (both connective and antagonistic) have helped establish an intimate, mutual bond between both countries. Certain chapters in this shared history are absent from the public discourse, yet surface in informal conversations between guests and hosts, ranging from Soviet deportations to Siberia and the Gulag, for example, or Ukrainian refugees in Poland who fled the Holodomor in 1930s to the cover-up of the Chernobyl disaster. Other topics, including Polish phantom pains resulting from the loss of territories in the East after the Second World War, are avoided entirely, even in informal conversations. Indeed, after the war, Poles migrated along similar East-West routes as Ukrainians travel today, from Lviv to Wrocław, a parallel displacement that has surely been noted by many. Among contemporary taboo subjects are also numerous and equally legitimate historical resentments held by Ukrainians against Poland, including Polish responsibility for the forced resettlements of Ukrainians and Lemkos during the ‘Operation Vistula’ in 1947, and the subsequent denationalisation and assimilation of the resettled populations in Poland, effectively putting an end to a centuries-long culture of the Subcarpathia region.

As a historian from Poland, who deliberately chose to conclude her reflections with a Ukrainian, and not Polish, lieu de mémoire, I sincerely hope that history will stop repeating itself in this part of Europe, including within the context of Polish-Ukrainian relations. By giving refuge to Ukrainians, Poland can choose to offer a path of integration that is marked by respect for their culture and language, instead of subjecting them again to full assimilation. Every effort must be made to resist the so-called post-colonial temptation, while any attempts to form another unequal union between Poland and Ukraine should be thwarted. Polish right-wing politicians have already proposed the “reactivation” of the 1569 Union of Lublin,[24] which created one state encompassing Polish, Lithuanian, Belarusian and Ukrainian lands, with Poland as the politically dominant primus inter pares. To their minds, this would introduce an unofficial two-tier structure to the European Union—a grateful Ukraine backs up Poland whenever the latter decides to oppose the “Brussel dictatorship”. This direction of Polish foreign policy – a close partnership between Poland and Ukraine and the defence of sovereignty against the “evil Brussels” – was recently confirmed in a long exposé by the Polish Foreign Minister, Zbigniew Rau.[25] The political right in Poland (bar its radical-wing faction) has become less vocal about its claims against Ukrainians, shifting toward an outlook that paints Ukrainians as a younger and unprivileged brother whom Poland has welcomed with open arms and a warm embrace and with the promise of joining a truly civilized Europe –preferably on their own terms, which are not necessarily in accordance with the liberal-democratic values of the current EU.

What gives hope for a more symmetrical Polish-Ukrainian partnership is the fact that Ukrainians have long been present in Poland, well before 2022, forming an effective diaspora of nearly two million people that has already countered the punches from the right-wing media on the subject of the Volhynia tragedy (including the discussion surrounding Wojciech Smarzowski’s 2016 film). The diaspora is a major factor in the Polish labour market and puts much energy in successfully debunking anti-Ukrainian myths. Finally, hope for an eventual break from the vicious circle of history can be found in the determination with which Ukrainians defend their statehood. May it quickly bring them their longed-for sovereignty.

This text has been written as part of the ERC-Project "Unlikely Refuge? Refugees and Citizens in East-Central Europe in the 20th Century' (grant agreement No 819461).

Lidia Zessin-Jurek, A History that Connects and Divides: Ukrainian Refugees and Poland in the Face of Russia’s War, Cultures of History Forum (20.04.2023), DOI: 10.25626/0145.

Copyright (c) 2023 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editor.

Lidia Zessin-Jurek · 20.12.2021

Trapped in No Man’s Land: Comparing Refugee Crises in the Past and Present

Read more

Interview · 08.03.2021

A Ruling Against Survivors – Aleksandra Gliszczyńska-Grabias about the Trial of Two Polish Holocaust...

Read more

Lidia Zessin-Jurek · 03.09.2019

Hide and Seek with History – Holocaust Teaching at Polish Schools

Read more

Maciej Czerwiński · 11.04.2019

Architecture in the Service of the Nation: The Exhibition ‘Architecture of Independence in Central E...

Read more

Marta Bucholc and Maciej Komornik · 19.02.2019

The Polish ‘Holocaust Law’ revisited: The Devastating Effects of Prejudice-Mongering

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).