16. Nov 2015 - DOI 10.25626/0046

Dr. Anna Muller holds a Ph.D. from Indiana University. She works as an assistant professor at UM-Dearborn. Her research interests include modern Polish and Eastern European history, gender, oral history, memory studies, and cultural history. Her most recent article "A More Manly Man.... Masculinities, Body, and Fatherhood in the 1980s Polish Political Prisoners’ Correspondence" is forthcoming in a volume on gender in Eastern Europe as part of 'Gender and History' series within Palgrave Macmillan. From 2010 to 2012, she worked as a curator for the Museum of the Second War in Gdańsk, Poland (scheduled to open in 2016), where she co-curated exhibitions on concentration camps and the Holocaust.

While the Museum of the Second World War is still awaiting the opening of its final location, its staff have prepared an exhibition that in 45 artefacts tells the story (or perhaps, stories) of the difficult process of transitioning out of war. The artefacts not only speak to us about the chaos and destruction that defined the post-war life, but also about the daily practices that helped people create the intervals of peace necessary to maintain their sanity in the midst of destruction.

Recently, I had a chance to observe a friend photographing an old Polish man holding a Polish Home Army banner. The photo session took place in Hamtramck, Michigan, where many Polish immigrants settled in the first half of the twentieth century. The old man, a former Warsaw Uprising insurgent, has lived in Hamtramck since relocating to the Unites States in 1968. The densely embroidered banner was made many years ago in a small workshop in Warsaw. It was almost too heavy for the fragile old man to hold up, yet he counted it his most precious possession. The patriotic banner serves as a tribute to resilience and life which continues despite trying circumstances. It triggers memories of the past and frames the present of the people around it. The banner inscribes the memory of the Uprising.[1] It does not speak through its craftsmanship or inspire awe with its message; rather, it speaks through the attention and practices that the old man embedded in it. Such objects serve as channels that help people adapt to their reality: whether as links between past and present, or as mediators between two seemingly separate worlds, the physical and the spiritual.[2]

The image of an old man cherishing his banner brought me back to an exhibition I saw a month earlier in Gdańsk, Poland, at the European Centre for Solidarity (hereafter, ECS). The exhibition, "45: The End of the War in 45 Artefacts," tells the story (or perhaps, stories), of the difficult process of transitioning out of war.[3] The curators are Paweł Machcewicz and Piotr Majewski, the directors of the Second World War Museum, and its employees, Oliwia Gałka, Łukasz Jasiński, and Marcin Westphal. Because the museum is still awaiting the opening of its final location, it is fitting that the inaugural ECS temporary exhibition was prepared by its personnel.[4] This exhibition is a preview of the exhibiting philosophy and the range of artefacts at the disposal of the Second World War Museum.

The ECS is located in an imposing building modelled after a ship at the gate to the Gdańsk Shipyard (formerly, the Lenin Shipyard). The building's design is a metaphor for the Solidarity movement that changed the dimensions of work and worker activities from a small communist industry. It is a metaphor for the openness and the change that Solidarity initiated. But today's Gdańsk Shipyard has only one small factory still functioning on site and the ECS building now visually dominates the empty space. It suggests more distance between the Museum and the shipyard workers—especially those who lost their jobs as a result of the economic transformation of the 1990s—than the creators of the Museum perhaps envisioned.

The Second World War Museum began collecting artefacts in 2009. At first this meant visiting flea markets and antique shops in hopes of coming across historical objects, in addition to establishing relationships with collectors all over the world. In 2011, the Museum announced a national call to collect war artefacts. Although proceeding at a much slower pace, the collection effort continues today.[5] As of now, the Museum has nearly 35 000 artefacts, which makes it one of the largest collections of historical artefacts in Poland. The decision to collect arose from the Museum’s mission to tell the story of the war through original objects, but this insistence on the importance of artefacts in itself tells a story. There is hope that to the extent that the artefacts represent authenticity, they constitute a milieux de memoire, "the real environment of memory," which embodies history, and as such can become, in the words of Paweł Machcewicz, "an inspirational incentive to reflect on the complexity of historical events […] and the ambiguities of their outcomes."[6]

Aesthetically, the temporary exhibition is in dialogue with the ECS décor. The panels in which the artefacts are displayed are curved to correspond with the walls of the ship. There is no multimedia and hence this is a rather traditional and simple presentation. It speaks through the objects and short labels that, while hardly explaining the intricate history of the items, at least capture the visitors' attention enough for them to engage the story presented. As the curators of the exhibition stress in the catalogue, all these artefacts "originated from the Polish land or lands linked with the fate of Poles, and, as such, they illustrate predominantly the east and central European experience."[7]

Writing about the Holocaust objects, Bożena Shallcross says that most Holocaust objects have "entered the frame of representation, playing the role of protagonist while signifying their absent users."[8] They are an illustration of the destruction. Once an artefact signifies tragically lost lives, it is very difficult to add anything to its meaning. The piles of shoes—well known among those who have visited older Holocaust exhibitions, or even the one burnt shoe salvaged from the Warsaw Uprising that we see at the exhibition under review—disturb viewers, but this brings little reflection beyond the rather empty "never again" sentiment. What inspired the curators of this exhibition was the hope that original objects, through the stories they carry, have the power to awaken compassion for the people whose lives were entangled in the complexities of the war.[9] Relying on the connection between an object and its story, the curators chose objects that signify not so much absence as process: people’s daily practices and attempts to come to grips with life in wartime circumstances; in particular, that moment when the war was about to end or had just ended, but the arrival of peace (which had not yet been fully achieved) was difficult to recognize.

In the catalogue, the curators explain that they decided not to impose any specific order on the artefacts (although they are divided into thematic groups), allowing visitors to circulate through the exhibition more freely. At first glance, visitors encounter typical war objects, such as military uniforms and propaganda posters as well as more individualized items, such as letters and personal memorabilia. The artefacts tell a story of fear, pain, violence and hope. The war, more than peace, is visible throughout: there is evidence of human loss and physical destruction, but there are also objects that represent desperate attempts to normalize the abnormal.

The catalogue, like the exhibition, is organized around nine themes that ultimately guide us not only through the exhibition, but also through the authors' understanding of the end of the war. Huge posters hang from the main entrance signalling the central themes: 1) terror and repression versus resistance and opposition; 2) Soviet domination, new borders and migration cycles, and the People’s Republic of Poland; 3) destruction and life reborn; and 4) German crimes and the fate of Germans after the war. Remaining in a dialogical relationship, these themes correspond with traditional Polish historiography that perceives the end of the war as either a coup or communist take-over that led to the establishment of Poland as at least a nominally communist state and a Soviet satellite.[10] It is a discourse based on the dichotomies of betrayal and faithfulness, loyalties either to the pre-war authorities or to the post-war Communist regime and its allies, destruction of the old and hope for the new, lives destroyed and lives reconstructed.

The exhibition presents examples of lives broken as a result of these divisions. There are the letters of Antoni Pajdak, a politician and delegate of the Polish government-in-exile, who in March of 1945 was arrested, tried at a secret tribunal in Moscow with fifteen other Polish politicians and leaders of the Polish Underground State, imprisoned, and consequently sent to Siberia. The letter in the exhibition is from 1945. Not knowing whether he survived the Soviet prison and fearing the worst, his wife committed suicide, and his daughter was imprisoned for her efforts to bring her father back to Poland.

But as the exhibition makes clear, exile to a Siberian prison was not the only method used to tame unrest in the country. There is a door to a solitary confinement cell from the prison on Kurkowa Street in Gdańsk, a prison that after 1945 was controlled by the Soviet NKVD. The label reminds the visitors that a similar door isolated 17-year-old Danuta Sledzikówna, known as Inka, who was executed in 1946 for her involvement in anti-Soviet partisan warfare. Another striking example of a broken life is the memorabilia and documents of the young woman, Janina Wasiłojć-Smoleńska. During the war, she served as a nurse in the 5th Vilna Brigade of the Home Army only to be imprisoned in 1947 and sentenced to death for her involvement in the insurgent struggle, which in 1944–45, turned against the Soviets. Polish heroes were becoming Soviet villains, and the Soviet retribution against them clearly marked the end of the war as a new conflict with Polish patriots. Janina’s sentence was commuted to 15 years, and she was released in April 1956. Her prison memorabilia include one of the letters she sent home from her cell. There is also a religious medallion and a bookmark that she embroidered in one of her cells using a fish bone and threads pulled from her clothes.[11]

While traditional exhibitions represent an attempt to "encode preferred memory," the "new museology" aims at a less top-down presentation, where knowledge is produced or co-authored with the visitors.[12] Taken at face value, this exhibition conveys a rather traditional message. It does confirm certain truths and meta-narratives, but the objects provide us with a chance to look at history as a process and a set of practices that people pursued in order to move forward, maintain their mental balance, or simply survive. If taken as a point of departure for reflection, many of the objects may normalize the establishment of the communist state. They open up ambiguities that challenge our meta-historical understanding of the end of the war as a violent struggle. Like a patriotic banner, they are less symbols of national history than indications of the practical and daily dimensions of history. To the extent that they present experiences that everybody can share, objects democratize history.

While the curators state that there is not one intended way of viewing the exhibition, for the sake of this review, I will divide the artefacts into two groups according to the purpose they served and the image of the war that they provide. The first group normalizes life during the war and the second presents war as ongoing, or as merely the inception of a new conflict. While some objects made daily existence bearable despite the fighting and privation, the other group points to behaviours and practices that prolonged the violence and blurred the distinctions between war and peace even though peace was already on the horizon.

A bucket made from an aircraft tank, a scoop for water or grain made out of a helmet, and even a pair of shoes made from car tires all have a lot in common. They tell us about scarcity, desperation, and resourcefulness, but also about how people managed to accept their wartime circumstances and live with its manifestations—the wide presence of military objects in daily life as well as a dearth of alternatives. War narratives are abundant in stories of people normalizing the abnormal. Life went on despite the chaos. The destruction gave a new texture to everyday life; it became the foundation of survival. Kazimierz Wyka, a Polish essayist and historian, in his book on life in occupied Warsaw described life during the war as ersatz, "life as if lived," or in Bożena Shallcross’s translation "life not quite lived."[13] What Wyka argues is that in circumstances of occupation, shortages, and lack of freedom, people create a substitute life that becomes real life. Creativity can make life easier and more stable, even in extreme circumstances. Norwegian archaeologist Bjonar Olsen noted that August Comte, the early nineteenth century philosopher, had seen things "as a grounding constituent for our mental equilibrium".[14] Objects defy the Cartesian divide between physicality and spirituality. They are a source of stability and, by extension, mental health.[15]

This exhibition illustrates how closely spirituality was intertwined with materiality to produce a sense of stability during the war. There is a metal ring (in fact a sanded fastening nut) that a Polish couple used as their wedding ring in 1946. One of the photos shows that in the midst of the destruction and ruins, the first beauty parlours began to pop up. Even if luxury was not appropriate to the circumstances, the mental respite that such places offered was welcomed. The owners of many of the artefacts defied the war without engaging in lofty ideas or resistance.

A particularly interesting group of artefacts reveals how people normalized war, or at least mentally and physically dealt with war trauma. These come from the concentration camps—souvenirs such as camp uniforms or various objects they used while in a camp. After the war ended, many former prisoners carried them home. Artefacts are certainly memory triggers, but in this case they probably functioned more as reminders of individual victory and resilience. We see a bell that Mauthausen-Gusen inmates made out of an old pipe they had found, which they took with them after the war. Or the prison uniform and such personal items as the knife, pencil, and calendar that Leszek Dobrowolski took home with him from Buchenwald, where he was imprisoned from 1943 to 1945. This collection of Dobrowolski's artefacts introduces a category of private life that was outside the direct control of the prison authorities: a calendar, for instance, allowed Dobrowolski to mark the passing days and gave him a fleeting sense of being in control of time.[16]

Interesting contradictions and parallels emerge if visitors venture to compare the various artefacts. Many artefacts remain in dialogue, the outcomes of which depend on how willing the visitor is to embrace the ambiguities of the war. We can see this in a set of tools that belonged to repatriated Poles (under the theme of new borders and mass migration) and a theodolite (under the theme of the People's Republic of Poland), an instrument used to measure the land. The tools belonged to a family who was forcibly resettled from eastern Poland after those territories were passed on to the Soviet Union in 1945 as a result of the Yalta Agreement. The theodolite indicates the process of appropriating and dividing the new land in the west that communist Poland took as compensation for its lost territories in the east. But the division of estates was also part of the land reform. Depending on the intentions of people reading the artefacts, both can suggest either terror and coercion or the hope that came with a new beginning.

The richness of the artefacts in this exhibition shows how closely the post-war peace cleaved to the war, or in other words, how ambiguous the post-war period was. In most cases, the normalization came at somebody's expense. The resettled found new homes on land that had belonged to somebody else. Parts that were used to create many objects for daily use often came from former Nazi plants, concentration camps, or even abandoned homes that the local population looted after the war. The post-war desperation was driven by the deprivation and demoralization the war had released. Even though the fighting had ended, people's behaviour and certain aspects of the post-1945 reality clearly indicate a prolongation of the wartime habitus rather than the rule of peace.

While most of the artefacts indicate the ambiguous nature of the peace in post-war Poland, some clearly show that the war in fact continued, if on different footing. The landmines are on display to remind people that the consequences of war continued after the war ended. The year 1945 brought with it demoralization, a thirst for revenge, and a new form of justice. The exhibition contains many examples that point to the controversial behaviour of Red Army soldiers. There are destroyed street signs from Gdańsk and Berlin that were brought home as war trophies by a Polish soldier who participated in the liberation of Berlin alongside the Soviet army. There is also a crucifix, probably shot up by a Soviet soldier (a bullet remains inside) that came from Lower Silesia.

The exhibition reveals the <em>ad hoc </em>justice imposed in revenge against the Nazis. One telling example is a bell from the Wilhelm Gustloff, a luxury liner, which on 30 January 1945 was torpedoed by a Soviet submarine, resulting in thousands of deaths and injuries, civilians as well as military. German civilians in Poland were targeted as responsible for crimes the Nazis had committed. Post-war authorities stigmatized the German population by forcing them to wear a yellow band with the letter "N" (for Niemiec, 'German' in Polish) that clearly resembled the yellow star that the Jews were forced to wear.

Perhaps one of the most controversial artefacts is an object referred to as a 'toy' in the catalogue that was made by a Soviet soldier and shows a sex scene. The curators of the exhibition have taken care to place it in a box that shields it from being easily viewed, especially by younger children. The 'toy' was found in a Soviet trench, in a map case that belonged to a Red Army soldier, probably a non-commissioned officer. Its caption explains that it tells us a lot about the needs of soldiers, but it suggests much more. As the caption also explains, it is a reminder of the plight of German women who experienced mass rape by Soviet soldiers. Estimates range from the tens of thousands up to two million.[17] The fear of rape also affected other women, those returning from concentration camps in Germany as well as others who considered themselves non-German natives of territories liberated by the Soviets. The initial statement of the label, which links sexual behaviour with the nature of the soldier's life, is disturbing; this object requires better contextualization. It points to Russian revenge and female suffering, but also remains a powerful and controversial metaphor for German victimization.[18] Unfortunately, without contextualization, it just confirms our assumptions about Soviet soldiers and perpetuates their reputation without reflecting on the larger consequences of this behaviour.

Another topic that seems underexplored is Jewish suffering during the war. The exhibition contains one artefact related to the meaning of 1945 for Jews. It is a <em>matzevah </em>from Pułtusk, near Warsaw, that was deliberately desecrated by the Germans and used as a cobblestone. This destroyed matzevah certainly resonates with the Jewish genocide, but the artefact may also have a post-1945 story. Many fragments from destroyed Jewish cemeteries were repurposed after 1945. To fully understand the meaning of the destroyed <em>matzevah </em>we need a larger context, which, unfortunately, one artefact with a short label cannot provide.

<p>In retrospect, what image of 1945 does the exhibition leave us with? When investigated carefully the artefacts provide us with multiple dimensions of 1945; peace that was difficult to recognize, war that continued in a new guise, people's attempts to normalize the abnormal, which, in the long run, highlights the destructive consequences of the war. In her discussion of the Holocaust, Shallcross maintains that it promoted the fetishization of objects: the acts of looting, amassing, and sorting gave unprecedented centrality to the fragmented material object.[19] In general, without the space for reflection and a fuller dialogue with artefacts, such objects function as witnesses, silent reminders, or relics of some curious or tragic past. But is this enough? Museum scholars contend that the goal of a deeply educational exhibition is to provoke "sustained attention, concern, and corrective action rather than a few days' sensation that is soon forgotten.[20]"

The new museology calls for exhibitions that embrace a "pedagogy of witness," one that challenges our easy perceptions and calls for thoughtful solutions. This should be a space where the past meets the present. To paraphrase Walter Benjamin, things are dialectical images, where the past meets with the present or where the past can evoke reflection about the present. Destabilization of old assumptions creates an educational moment, full of uncertainties, when openness and learning can occur. As Roger Simon asserts in his article on curatorial pedagogy, new exhibitions should be a provocation, but a provocation that ultimately provides an outlet for structuring the feeling or thoughts that came out of it. In other words, they should provide a platform that would allow visitors to deal productively with the emotions encountered when viewing the exhibition.[21]

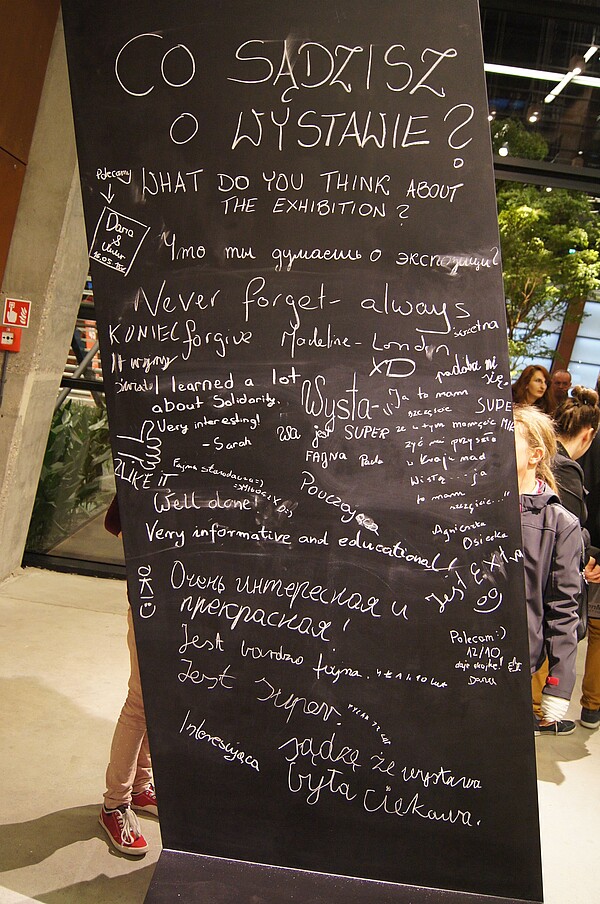

Does the exhibition on 1945 provide a space for dialogue? Does it destabilize our more traditional understanding of history? There is in fact an attempt to provide a dialogic space in the form of a blackboard where people can record their reflections, but it is quite small and it is not clear that anything is done with the responses. Still, the selection and the variety of the artefacts clearly express complexities and ambiguities that challenge master narratives, even if one such narrative provides the framework for the exhibition. The objects collected here challenge clear dichotomies between peace and war, victory and failure. They may call up old stereotypes, but they also carry potential counter-narratives, though certain objects might benefit from more extensive descriptions. The stories artefacts tell with a bit more investigation can help us recognize other, less commonly explored, aspects of the end of the war. How can the artefacts speak without our making that extra effort, if we lack the incentive to engage with them? Here is probably the major shortcoming of this rich and multifaceted collection. But can we really expect more from a small and temporary exhibit? Perhaps at this stage we should treat it as a first effort, with enormous potential still hidden in the stories that the artefacts can reveal. It is certainly a show that has multiple dimensions and suggests the richness of the Second World War collection. As such, it should entice us to visit the permanent exhibition, once the museum opens.

Anna Muller: When History Speaks Through Objects... "45: The End of the War in 45 Artefacts". In: Cultures of History Forum (16.11.2015), DOI: 10.25626/0046.

Copyright (c) 2015 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

Lidia Zessin-Jurek · 20.04.2023

A History that Connects and Divides: Ukrainian Refugees and Poland in the Face of Russia’s War

Read more

Lidia Zessin-Jurek · 20.12.2021

Trapped in No Man’s Land: Comparing Refugee Crises in the Past and Present

Read more

Interview · 08.03.2021

A Ruling Against Survivors – Aleksandra Gliszczyńska-Grabias about the Trial of Two Polish Holocaust...

Read more

Lidia Zessin-Jurek · 03.09.2019

Hide and Seek with History – Holocaust Teaching at Polish Schools

Read more

Maciej Czerwiński · 11.04.2019

Architecture in the Service of the Nation: The Exhibition ‘Architecture of Independence in Central E...

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).