17. Apr 2020 - DOI 10.25626/0111

Karolína Bukovská is an MA student of Public History at the Free University Berlin. Her research interests include the oral history of the Shoah and the public representations of history, especially in museums. During her studies in Prague and Berlin she gained first curatorial experience. As a student assistant at the Foundation for the Study of Communist Dictatorship in East Germany, she is particularly interested in the museal depiction of the communist period.

Not so long ago, I travelled from Berlin to Prague and happened to share a compartment with two young English-speaking women. The train had just crossed the German–Czech border and my fellow passengers started to prepare for the next stop on their trip around Europe. “Look, there is a museum of communism!”, one of them exclaimed, while looking at the tourist platform Tripadvisor on her smartphone. Their subsequent conversation concluded with a definitive decision to go and have a look. It was then that I realized that I might see them again, or other backpackers like them, at the Museum of Communism. This private museum, which had been in operation for almost two decades, was also on my agenda for the semester break in Prague. However, the purpose of my visit was quite different from that of my fellow travellers. Rather than following Tripadvisor’s suggestions, I wanted to find out why it had never occurred to me, a Czech student of contemporary history and a person interested in museums, to visit the only exhibition that is dedicated to the period of communist party rule in Czechoslovakia. Why is it that, according to official statistics, one of the most visited museums in Prague attracts mainly international tourists and is basically ignored by the Czech population?

The following analysis of the Museum of Communism and its permanent exhibition is an attempt to answer these questions. It recapitulates the museum’s founding history and refers to three aspects of the museum: the private character of the institution, its target audience and the visual depiction of the life under communist party rule. This focus should highlight the specific position of the Museum of Communism among other domestic institutions.

It may seem ironic that the creation of the first museum dedicated to the period when Czechs were ruled by the Communist Party was the result of private entrepreneurship. Indeed, the Museum of Communism was established in 2001 by the American businessman Glenn Spicker, and this was possible only thanks to the transformed Czech economy and with Western capital. As the Guardian journalist Kate Connelly observed at the time, this was “the anti-capitalist era … turned into a free market commodity”.[1] Spicker had moved to Europe in the mid-1980s – first to England, then to West Germany where he studied and travelled around the divided country. After the wall came down in 1989, the young traveller moved to the other side of what had been the Iron Curtain and settled in Prague. Without having any concrete business plan, the American was determined to make use of the new opportunities offered by the nascent capitalism in post-communist Czechia. His first enterprise was a jazz club called U malého Glenna (Little Glenn’s) and it was followed by a chain of restaurants called Bohemia Bagel. However, at some point, as Spicker confessed in a 2015 interview for Radio Prague, he was tired of the restaurant business and tempted to find a new gap in the market.[2]

When asked about how he came up with the idea to create the Museum of Communism, Spicker relayed how he kept wondering what Prague was missing and what experience people lacked. As a historically interested former student of international relations, he gained the impression that twelve years after the Velvet Revolution, Czech society tended to neglect its communist past. In a CNN report from 2009, later posted on the CNN YouTube channel, Spicker claimed that “Czechs don’t talk about it” and that there was little interest for a museum dedicated to this period. This alleged lack of public discussion about the recent past, along with an ever growing number of tourists in the Czech capital, eventually brought the Prague-based American to the conclusion that a museum of communism “would be a great idea which will work.”

The original location of the newly founded Museum of Communism was characteristic for the transformation of Prague’s historical core into a city centre of ‘Western standards’. Situatedin the former ballroom of the baroque eighteenth century Savarin Palace, along the former medieval city wall, the museum was part of the now busy shopping street Na Příkopě. Being within walking distance to Wenceslas Square, which is the site of some of the most significant demonstrations against the communist regime in November 1989, was rather coincidental. Somewhat ironically, again, the new Museum of Communism shared a floor with a casino, a McDonald’s is nearby. In Savarin Palace, a symbol of cultural heritage, the commodified communist past and a symbol of globalization coincided.

The exhibition in Spicker’s Museum of Communism is assembled from his own personal collection of more than 1,000 items. He spent several months (and altogether $28,000[3]) roaming through flea markets and junk shops looking for remnants of the past which the locals “would just throw out”, as he put it. The ‘treasures’ he found were going to become part of his next business enterprise: there was a plough from a collectivized farm, border checkpoint machine guns, anti-American posters, chemical-warfare protection suits, and statues of Lenin and Marx. The exhibition eventually also displayed a recreated interrogation room, a classroom decorated with Soviet and Czechoslovak flags and a half-empty shop with just two types of tinned food. This was an attempt to “reconstruct what life was really like” in Czechoslovakia “under communism’s shadow from 1945 to 1989”.[4] However a video, taken by a visitor in 2017, shows that rather than a plausible illustration of everyday life before 1989, the museum situated in the confined spaces of Savarin Palace resembled more a cabinet of communist curiosities.[5]

For a period of 15 years, both life under communism and the products of the McDonald’s franchise could be experienced almost simultaneously. In the summer of 2017, the museum moved only few hundred metres down Na Příkopě streetto Republic Square where its new neighbours included the Austrian supermarket Billa and a Czech chain restaurant. Along with the relocation came a revision of the permanent exhibition. As the museum’s founder put it in the 2015 Radio Prague interview, “it has been a long time and [the exhibition] needs to grow”; the revision would make the exhibition “much better and bigger” and would bring it up “to the modern era”. Housed in a space of nearly 1,500 square meters, the number of exhibits on display was nevertheless significantly reduced. The scenes from the “communist reality”- section, originally filled with countless objects, were replaced by explanatory texts which form the main axis of the current display.

The new permanent exhibition is comprised of 62 panels depicting the history of Czechoslovakia in the twentieth century from 1918 to 1989. In a manner similar to its previous incarnation, the development of Czechoslovak communism is narrated chronologically along a “three-act tragedy” called “the dream, reality and nightmare”.[6] The concept was designed by Czech-born documentary film maker Jan Kaplan who was recruited by Spicker to design the museum already in 2001. ‘The dream’ covers the foundation of Czechoslovakia in 1918, the beginnings of the communist movement in the 1920s and the events and the aftermath of the Second World War, which both played a crucial role in the later establishment of the communist regime. The 41-year-long rule of the Communist Party, beginning with the February putsch in 1948, is divided into the remaining two parts: ‘reality’ and ‘nightmare’. The latter describes the 1950s, the era of political oppression, show trials and labour camps. The nightmarish atmosphere of this period is evoked by a dark ambience which stands in contrast to the clear, white walls in the rest of the exhibition. The section addressing reality attempts to describe daily life under communism in Czechoslovakia.

The new exhibition area alsoincorporates some of the earlier installations, for example the shock worker’s workshop, the school classroom with a mannequin of a member of pioneer organization, the ‘socialist shop’ and the interrogation room. The whole display is accompanied by photographic material from several archives, and the personal collections of prominent Czech photographers. The objects collected by Glenn Spicker, which according to the curator Alexander Koráb are “in 90% of all cases original”,[7] were restricted to a selection of items illustrating the explanatory descriptive texts. Thanks to the rather restricted use of three-dimensional exhibits (in comparison with the former exhibition), the Museum of Communism definitely does not resemble an overfull cabinet of communist curiosities anymore. Because single objects are often placed in a glass display case as unique remnants of the past, it is somewhat closer to ‘traditional’ museum exhibitions. Such a professional presentation, however, does not change the fact that the collection consists mainly of random findings from flea markets that lack proper description or further contextualization. Thanks to videos produced by visitors of the earlier exhibition and posted on Youtube, we are able to observe the transformation of the objects from a collection of curiosities to a seeming museum exhibit.

Nevertheless, according to the official museum’s website, the revised exhibition “provides a suggestive view of life in Communist-era Czechoslovakia” and “provides visitors with an authentic feel of the era”. Apart from the origin of the collection and rather distinctive treatment of displayed objects, there are some other aspects that make the project of the American entrepreneur a special kind of museum institution.

Since the establishment of so-called wonder rooms during the Renaissance, the notion of a museum has changed many times, and so has its function and the role that we attribute to this institution in society.[8] Most recently, the term ‘museum’ has become a subject of disputes also among the members of the International Council of Museums (ICOM).[9] The impulse for these discussions was the proposal for a new alternative museum definition. Whereas the definition adopted in the ICOM Statutes in 2007 regards a museum as

a non-profit, permanent institution in the service of society and its development, open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment for the purposes of education, study and enjoyment,

the new definition, which is twice as long, assigns museums a more inclusive attitude and active engagement with all possible challenges of the contemporary world. Regardless of the final outcome of these debates, the core of any museum’s activities remains identical: their task lies in acquisition, conservation, research, communication and exhibition of the material and immaterial heritage of humanity and its environment. It cannot be denied that the Museum of Communism, in a way, does fulfil these criteria. However, there is one aspect where the older as well as the new suggested concept of a museum are in agreement and which would probably exclude Glenn Spicker’s enterprise from the ICOM community, namely that museums are “non-profit institutions”.[10]

It is not just the founding history of the Museum of Communism but also some other features that hint at the institution’s orientation towards profit. For a private museum, as for any other free market commodity, advertising plays a crucial role. The promotion of the Museum of Communism takes place on different channels. The usual posters, found in the most frequented areas of Prague, are accompanied by the “stamps of quality” found on the museum’s website: visiting “this amazing museum” is recommended not only on Tripadvisor, but also by BBC, CNN, TIME magazine or the Lonely Planet travel guide. Apart from that, the museum promotes itself also through “Communism tours” – a special type of sightseeing for tourists in Prague. Offered and carried out by a Czech private travel agency, these tours include a 1.5 hour long visit to the exhibition with the agency’s own guide and themed walk through Prague’s city centre. The travel agency has shot a promotional video tour through the new permanent exhibition, which serves as an advertisement for both partners in this joint venture. Further evidence for the museum’s interest in maximizing its earnings is represented by the entrance fee. At 380 CZK (roughly 14 Euro) for adults and 290 CZK (11 Euro) for students, tickets for this museum are way above the average ticket prices for any public museum in Prague.

Other indications of the rather commerce-oriented character of the Museum of Communism are the items sold in the museum shop. They differ considerably from those on offer in public institutions. Once visitors enter the platform above the exhibition where the museum shop is located, they experience a kind of déjà vu because the range of products very much resemble those found in numerous souvenir shops in Prague’s Old Town. Apart from propaganda posters or magnets featuring the caricature of Lenin, the gift shop of the Museum of Communism is flooded with matryoshkas – Russian wooden dolls which have been sold for many years in souvenir shops in the Czech capital, to the incomprehension and outrage of many locals.

In fact, a matryoshka with aggressively bared teeth has been a poster ‘mascot’ of the Museum of Communism during the first years. Now, it can be purchased in the museum’s gift shop notably overpriced in doll form, as a bottle opener or a toothpick container. Nevertheless, the shop also offers some truly typical Czech products, for example, a specially brewed beer designed for the Museum of Communism and costing six times more than a regular bottled beer sold in a supermarket.

Besides these souvenirs, the museum shop offers books, somewhat conventionally. However, the brief introduction to Czech history in French, or the museum’s own English publication “Legacy” (which is a substitute for the non-existent exhibition catalogue) obviously does not aim at Czech readers. The range of products in the museum shop points to another specific feature of the Museum of Communism: apparently, it is not just the items in the shop but the museum as a whole that is oriented mainly towards international visitors.

In yet another interview in 2010, Glenn Spicker recalled that when he established his new business back in 2001, the museum was intended to be “a place for people to learn about communism”.[11] In the already previously mentioned promotional video clip“Inside the Museum of Communism”, the entrepreneur emphasizes that the exhibition was always meant to be done “by and for Czech people”. At the same time, he admitted to be also aiming at an international audience who could not understand “how different life [under communism] was”.[12] However, soon after the opening of the Museum of Communism back in 2002, it turned out that the ambition to attract the local population was less than successful: as Guardian journalist Connelly noted sarcastically, the Czechs obviously preferred a visit to McDonald’s over one to Spicker’s museum.[13]

Almost 20 years after its establishment, and three years after its substantial renovation in the new location on Republic Square, the number of museum visitors has not changed. The rather sceptical attitude of most locals towards the private museum is illustrated in a short video clip shot by one Czech visitor during the Museum Night 2018 – an annual event which allows free entrance to museums at a late hour. Standing in front of the entrance, the man invites his girlfriend with the sentence: “Let’s have a look [at] what kind of nonsense this is...”. Such a prejudice, of course, may not be shared by all Czechs. However, the fact that the Museum of Communism is still predominantly visited by international tourists suggests that this visitor’s scepticism might not be an exception.

The museum seems to have adopted to this reality. Despite Spicker’s original proclamation that the museum is done for locals as well, the current curator of the exhibition, Alexander Koráb, declared in a recent interview that the targeted audience has always been tourists from abroad.[14] Whatever the intention, a closer look at the exhibit clearly reveals the focus on non-Czech visitors. Even though every text is in both Czech and English, all English titles are notably, almost three times larger. Other information as well, such as the name of the museum at the entrance door and the labels in the museum shop, is predominately in English. This detail is, by the way, also the first thing that catches the attention of the aforementioned Czech video-maker: while entering the museum, he notes that “everything is in English here”.

A further walk through the exhibition reveals that apart from the language, also the narrated content is adopted to the international audience. However, only visitors coming from the USA can feel directly addressed, as the explanatory texts make various references to events and phenomena from the US-American history and the popular culture: the automobile manufacturer Škoda from the west-Bohemian city of Plzeň is presented as the “European General Motors”, the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968 is paralleled with dramatic events which shocked the American public earlier that year (the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy) and finally, the first Czech musical film The Hop-Pickers (Starci na chmelu) from 1964 is described as “a kind of forerunner of Grease starring John Travolta”. These references seem as if they reflected the (national) perspective of the museum’s founder and at the same time excluded the point of view of other ‘Western’ and non-Western countries.

One striking example of this ‘American influence’ is the East-West timeline, which offers a recapitulation of the most important events in the communist Czechoslovakia (‘East’) and brings them together with the events of that particular year in the ‘West’. The majority of chosen ‘Western’ events, similarly to the panel texts, refers to the recent decades in the United States (the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the landing on the moon or the founding of Microsoft). Additionally, some of the comparisons made seem to reveal remnants of a Cold War mind-set. Thus, the massive show trials in post-war Czechoslovakia are juxtaposed with the testing of the polio vaccine in the USA; the year 1955 is represented by an image of the unveiled Stalin monument in Prague and the opening of the Disneyland in the same year.

One of the reasons why some Czechs might perceive of the Museum of Communism as “nonsense” might lie in the fact that the locals do not have to automatically relate to the exhibition’s depiction of the communist era. Indeed, some of the displayed objects, such as statues and busts of “the fathers of communism”, propaganda posters or paintings depicting shock workers can be found in a number of Czech regional museums as well.[15] In the Museum of Communism, however, these items seem to send out a form of “communist kitsch”. The omnipresent propaganda posters, the statue of Karl Marx, the aforementioned matryoshka, or the selfie point with the life-sized statues of Stalin and Lenin: such display of the communist past responds to a rather stereotypical picture of the “Eastern-Bloc-Other”,[16] not necessarily shared by most Czechs, or visitors from other post-socialist countries.

This perspective may originate in the very story of how the various objects for the exhibitions came to the museum. Just like in the first exhibition in the Savarin Palace, also the current exhibition revolves around objects from Glenn Spicker’s private collection. Collecting the remnants of the communist past was originally his hobby. Thus, in a manner that is markedly different from the acquisition process of public museums, Spicker’s collecting process was not driven by any system, but most likely by his personal interests and preferences. For this reason, the objects in the permanent exhibition of the Museum of Communism today may foremost reflect his personal vision of life behind the Iron Curtain rather than the established historical knowledge or real experiences. His vision, in turn, corresponds far better with life under communism as it is imagined by international visitors, especially if they come from Western countries. Due to this fact, and even though the Museum of Communism of today gives off the impression of a regular museum institution, its permanent exhibition remains something of a cabinet of communist curiosities.

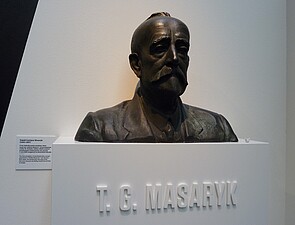

When it comes to the curiosities presented in the exhibition, there is one particular object that makes the visitor who has been socialized either in socialist ČSSR or post-socialist Czechia to doubt the trustworthiness of the entire display. Coincidentally, it is the first three dimensional object which catches the eye after entering the exhibition. Next to the text about the foundation of Czechoslovakia in 1918 stands a bust of the first Czechoslovakian president. However, this bust of unknown origin – in fact, none of the objects in the exhibition provide proper descriptions or indications of their origin – resembles Tomáš Gariggue Masaryk only very remotely. Whereas this inaccuracy can make the locals either angry or laugh, it probably remains unnoticed by the majority of the visitors coming from abroad. This concrete example, along with the questionable treatment of the objects in general, further strengthens the overall impression that the Museum of Communism serves rather as an attraction for international tourists than as a place for the Czech population to contemplate its recent past.

In November 2019, Czechia commemorated the thirtieth anniversary of the Velvet Revolution. Remarkably, not a single public museum chose to exhibit anything addressing the entire period of the communist regime. The private Museum of Communism in the city centre of Prague remains the only permanent exhibition dedicated to communist Czechoslovakia between 1948 and 1989. Yet this is about to change. In September 2019, the Prague city council approved the founding of a new “Museum of 20 Century Memory”. With the recent removal of the controversial statue of Soviet Marshal Konev, it acquired the first item to its collection.

In February 2020, the renovation of the former communist-era prison in the South-Moravian town of Uherské Hradiště began in order to turn it into a memorial museum by 2028.[17] Soon, Glenn Spicker’s project will no longer be the only player in Czechia when it comes to the musealization of the Czech communist past.

Nonetheless, the Museum of Communism deserves greater attention – not only due to its relatively high visitor numbers. It represents a specific case in which a somewhat problematic relation to the recent past (symbolized by the total absence of a museum) was turned into a successful business enterprise. Its founding history, along with the emergence of similar commercial projects such as the “communism tours” or several escape rooms across Prague that feature communist-era themes, raises questions about what the functions of a contemporary museum should be and which interests they actually follow. Furthermore, the fact that the exhibition’s narrative is targeted towards an international, rather than a domestic audience can be criticized; it can also serve as an inspiration to look at the Czech communist past from different perspectives and to see it in a broader context.

Karolína Bukovská: Museum or Tourist Attraction? The Museum of Communism in Prague. In: Cultures of History Forum (17.04.2020), DOI: 10.25626/0111

Copyright (c) 2020 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

Patrick Metzler · 21.12.2022

Localizing “Our Germans”: The New Permanent Exhibition in Ústí nad Labem

Read more

Veronika Pehe · 11.05.2022

‘The Nineties’ on TV: Remembering the Transformation Era in Czech Popular Culture

Read more

Jiří Smlsal · 25.01.2022

The Stench of Pigs and the Authority of Historians: Czech Debates About the Lety Concentration Camp

Read more

Karolína Bukovská · 25.11.2021

(Re)construction of Czech History: The National Museum and its New Permanent Exhibition on the Twent...

Read more

Veronika Pehe · 21.07.2021

Czech Prime Minister Implicated as Communist Secret Police Agent – Yet Nobody Cares

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).