25. Nov 2021 - DOI 10.25626/0133

Karolína Bukovská is an MA student of Public History at the Free University Berlin. Her research interests include the oral history of the Shoah and the public representations of history, especially in museums. During her studies in Prague and Berlin she gained first curatorial experience. Her main interested is in the museal depiction of the communist period and she currently works as museum educator in the National Film Museum.

It is quite easy to get lost in the labyrinth that is the new permanent exhibition, History of the Twentieth Century, at the National Museum in Prague. The space is so confined: there are trenches resembling those from the First World War, fake building facades with a falling Austrian coat of arms, a grocery store from the 1930s, a Soviet tank replica and plenty of displays behind glass. Unique exhibits are mingled with less original objects. Stretched over a spacious ground floor and two elevated platforms, a seemingly endless number of objects are displayed alongside full apartment interiors and utensils from different eras. Yet despite this variety of objects, I had the overwhelming sense that I had already seen all of it before: at school, on television or in my grandmother’s kitchen.

It took twelve years of preparation to finally open this new permanent exhibition at the National Museum. It represents 90 years of the history of the Czech Republic – from the outbreak of the First World War until 2004, when the Central European country joined the European Union. However, when the exhibit finally opened in July 2021, it provoked rather mixed reactions. Local historians compared it to an “illustration of a slightly outdated history textbook,”[1] further criticizing the marginalization of national and other minorities and the absence of a narrative.[2] Starting with a brief introduction to the Czech National Museum and a recapitulation of the decade of reconstruction, this review of the new exhibition will follow the description of the exposition provided by the museum itself and discuss three main points of criticism: the exhibition’s educational function, the question of a target audience and the missing narrative. In conclusion, I will propose suggestions on how the National Museum could prevent its shortcomings in the future.

The National Museum is the largest and the central state museum in the Czech Republic. With its collection, scientific, educational and methodological functions, as the museum's website states, “it seeks to enhance the sense of national identity and awareness of being part of the whole framework of European and world community and culture.” Founded in April 1818 in Prague as the Patriotic Museum (Vlastenecké muzeum), the institution was originally an initiative of the mainly German-speaking aristocracy residing in the Kingdom of Bohemia – back then, part of the multinational Habsburg Monarchy. The founders and supporters of the museum were interested in an enlightened collection and study of objects related to the local history. However, during the so called Czech National Revival in the nineteenth century and thanks to the engagement of the prominent historian and politician František Palacký, the museum gradually became an important factor in the process of forming a modern Czech nation.[3] In 1848, it was renamed the Czech Museum (České muzeum) and in 1922, four years after the declaration of the Czechoslovak Republic, the museum received its current name, the National Museum (Národní muzeum).

Since 1891, the National Museum has been located at the monumental neo-renaissance palace on top of Wenceslas Square, historically one of the most important squares in Prague. Today, the institution also occupies several other buildings in the Czech capital, including the former seat of the Czechoslovak Federal Assembly. The National Museum consists of five main departments: the Natural History Museum, the Historical Museum, the National Museum Library, the Czech Museum of Music, and the Náprstek Museum of Asian, African and American Cultures. The various collections consist of more than 20 million objects from diverse fields: from mineralogy and zoology to ethnography and musicology. For 130 years, the most famous exhibit and the mascot of the National Museum, as the museum shop suggests, is the 23-metre-long skeleton of the fin whale.

In July 2011, the historical building at Wenceslas Square closed its doors due to plans to restore and partially reconstruct the building. It was the first such extensive restauration since 1891. The work took 42 months and the costs were reported as reaching 70 million euros. Yet, thanks to the reconstruction, the overall exhibition area was expanded by up to 30 per cent.

The historical building opened again in October 2018, on the occasion of the centenary of independent Czechoslovakia and the bicentenary of the National Museum itself. The result of the reconstruction was visible upon first sight. The monumental neo-renaissance palace at Wenceslas Square, a national cultural heritage site, shone with its restored light brown facade.

The extensive renovation also included the preparation of several new permanent exhibitions. The opening of these displays, dedicated to history, natural history and the history of humankind, was originally planned for June 2020,[4] but it was repeatedly postponed, partially due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Despite the importance of the National Museum as the central state museum, there were no public discussions about the institution’s mission or the concept of the upcoming exhibits for much of the extended reconstruction period. The planned exhibition dedicated to the twentieth century (the nineteenth century up to the outbreak of the First World War would eventually be presented in a separate exhibition) especially became a subject of much speculation.

Only in October 2018, when the National Museum was partially reopened, could the public get a glimpse of what the museum was to become when the cultural-historical journal Dějiny a současnost (‘History and the present’) published excerpts from the exhibition’s concept and script. Michal Stehlík, historian and assistant director of the National Museum, outlined the planned modern history exhibition with the following words:

From the museum’s presentation perspective, it became clear that we should not merely create an informative overview of historical events. Rather, it is necessary that we stress the uniqueness of the object, that we connect information with emotion, and that we respect the structure of the expositions with regard to the particular target groups.[5]

So, did the exhibition ultimately succeed in reaching such an ambition?

The permanent exhibition is located in the New Building of the National Museum. Before the visitors enter the actual exhibition space, they are confronted with an interactive map of Europe presenting the changes in state borders between 1914 and 2004. This visualisation is the first and the only reference to an international context. The rest of the exhibition is all about Czech people and “their” collective past.

After entering the exhibition, the visitors find themselves in the trenches of the First World War. They are immediately invited by the museum custodian to enter the “time elevator,” a separate round room. In there, a six-minute visual projection, as the official exhibition description states, creates “the illusion of an elevator travelling through time and introducing key moments of the 20th century.” This immersive experience serves as an introduction to the exhibition. In chronological order, it presents familiar pictures and sound recordings from the ninety-year history of Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic. The visuals and the sound effects highlight the “good times” – the First Czechoslovak Republic (1918–1938) and the democratisation process of the Prague Spring in the 1960s. Both World Wars as well as the show trials at the beginning of communist rule (1950s) clearly stand for the “dark times.” The era of “real socialism” in the 1970s and 1980s is illustrated through the colour red and is depicted using symbols of the communist regime (May Day parades, blocks of flats) as well as the popular culture of the time. Given recent survey data which shows that Czechs are generally “not keen on the EU,” it is surprising that the Czech Republic’s EU accession in 2004 is portrayed as some kind of triumphal end of history.

After the audio-visual show, the exhibition continues to the interwar period, but from this moment on, the journey through the Czech twentieth century becomes chaotic. Despite an almost 2,000 square-meter area, the visitors are confronted with a rather confined space filled with a labyrinthian arrangement of black blocks and glass vitrines. The rather unusual division of this part into three thematic sections – public, semi-public and private spaces – is not sufficiently explained. Moreover, the historical milestones that are emphasized in the description (1914, 1918, 1945, 1948 and 2004) can hardly be visually recognized in the room. What clearly dominates at first sight is the display of everyday-life items. There are installations of interiors (from an interwar maid’s room to a 1990s living room) and objects presenting popular and consumer culture.

Furthermore, the exhibition includes two elevated platforms above the core of the display. The first one is the interwar luxurious tailoring salon Bárta, which was moved to the museum from its original location in the centre of Prague. The second platform is dedicated to the world of politics. It is symbolically levitating above the “lives of ordinary people” on the ground floor. Almost one hundred busts of various personalities of the twentieth century – mainly politicians – are presented here, in the so-called ‘bust hall’. The authentic busts are complemented by smaller 3D glass portraits of low aesthetic quality.

Several touch screens accompany the installations and glass displays, located along the walls throughout the exhibition. They present additional archival documents and audio-visual material. Some of them include thematic games and quizzes, inviting interaction with the visitor. However, these additional elements do not interact with one another, and it is sometimes quite difficult to find them. Towards the end of the exhibition, there is a children’s playroom inviting the youngest visitors to discover games their parents and grandparents used to play. The display ends with a live camera feed of Wenceslas Square and a sign reading: “Thank you for visiting and welcome to the present.”

In a press release by the National Museum issued on 22 July 2021, the day of the exhibition opening, the museum’s general director Michal Lukeš is quoted saying that the exhibition“has the ambition to show the key events of our modern history [...] and to educate in an engaging and interactive way.” Unfortunately, the exhibition does not have the best preconditions to become, as stated in the press release, “an important place of education.” One of the reasons might be the insufficient work with the exhibited objects. Most of the exhibits serve purely as illustrations. Historical documents are hanging on the walls like colourful collages without any contextualization. Many history textbooks used in Czech elementary schools present copies of historical sources and photographs in a similar non-analytical way. Even though this approach is slowly changing, for instance thanks to apps like HistoryLab, which was developed by the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes’ Education Department and which supports critical work with historical sources,[6] generations of Czech pupils have still grown up with this kind of history education. That is why many reviewers, myself included, were reminded of browsing through a rather unintriguing textbook while walking through the exhibition.

Equally problematic is the overwhelming number of presented objects (nearly one thousand in total). The overcrowded exhibition area looks as if the curators could not agree on the right object for any given theme. As an example: in one glass vitrine we see an expedition kick-scooter from the 1960s, a 1980s skateboard and a pair of children’s exercise shoes from 2000. We learn that in 1969, the hotel waiter and adventurer Václav Hošek travelled 2,500 km across seven European countries with this kick scooter. The stories behind the skateboard and the shoes and their connection to the vehicle remain unclear. Such a way of presenting these objects, which might resemble the practice of designing a shop window, leads to several, not necessarily logical juxtapositions and stands in stark contrast to Stehlík’s statement about the necessity of stressing “the uniqueness of the object.”[7]

Moreover, the uniqueness factor often lies in the presentation of certain items as relics. The visitors can take a look at the handkerchief of the president Edvard Beneš or the suit of the former General Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, Miloš Jakeš.

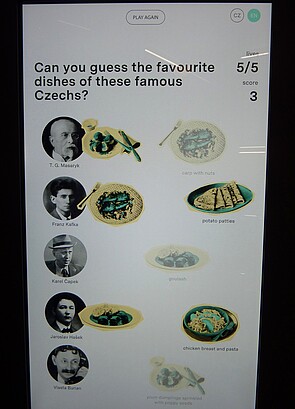

The interactive elements in this part of the exhibition unfortunately do not strengthen its overall educational function either. They often involve guesswork on the part of the visitor – for example, what were some of the favourite culinary dishes of famous Czechs? While pondering who might have enjoyed carp with nuts (the answer is Franz Kafka, who is, without any further explanation, regarded as Czech), I wonder how this exercise can help us better understand the history of the twentiethcentury.

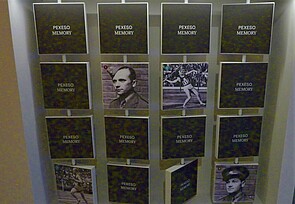

Outdated principles of history education are demonstrated in the game at the very end of the exhibition. There are 16 cubes, again with faces of famous Czechs. The goal is to find the matching pairs, like in a memory game. Apart from their visual memory, the visitors are also testing their knowledge of “famous couples”– for example, Jozef Gabčík and Jan Kubiš (paratroopers who assassinated Reinhard Heydrich) or athletes Emil Zátopek and his wife Dana. While thinking that I am too old for such a game, I moved slowly towards the exit. I was surprised when the custodian encouraged me to test “whether I know all of them.” Regardless of the age of the players, this activity suggests that learning about the past is about memorizing faces of people who are labelled as national heroes.

In his review, the historian Petr Zídek quite rightly bemoans the fact that the new history exhibition at the National Museum is “completely Czech-oriented.”[8] Indeed, the exhibition clearly appeals exclusively to a local, Czech audience.

Most striking is the absence of Slovaks with whom the Czechs used to share one state from 1918 until 1992 (with a short interruption during the Second World War when Slovakia became independent, albeit only as Nazi Germany’s satellite). If at all, they are represented by rather dubious figures, such as the leader of the clero-fascist Slovak State (1939–1945), Jozef Tiso, or the implementor of Normalisation (1969–1989), the communist president Gustáv Husák. The neglect of the Slovak’s share in the history exhibited here is all the more startling if we consider the very location of the exhibition – the former parliament of the Czecho-Slovak Federation.

To find representation of the German or Jewish populations in this exhibition is even more difficult. The visitor needs to pay extra attention in order to spot them among the exhibits. Indeed, the existing references to the multicultural history of Czechoslovakia are easily lost in the previously mentioned mass of objects. Moreover, the diversity of contemporary Czechia is also completely omitted. This became particularly evident during my visit when I saw a Czech-Vietnamese girl walking through the museum with her classmates. Would she find any reference to her community, which is a rather sizeable group of roughly 60,000 people in contemporary Czech Republic, in this exhibition? Equally absent are the Czech Roma and Ukrainian communities.

The overall orientation of the exhibit towards an ethnic-Czech audience and its knowledge stemming from elementary education can be demonstrated in one particular example:

In one of the displays representing the events of the Second World War, there are two objects: a helmet containing the Czech coat of arms and a bullet hole through it, and a white armband with red letters reading ‘RG’. The object descriptions say, both in Czech and English: “Helmet of a participant in the 1945 Prague uprising” and “Revolutionary guards’ armband, 1945.” There is no further explanation. For an international audience, it will remain a mystery what these objects represent. The local visitors have the advantage here as they may still recall the date 5 May 1945 from their history exams – the date when the uprising against the already-weakened Nazi regime broke out in the Czech capital. Czech people might also associate the white armband with scenes from famous feature films.[9] In short, the exhibition heavily relies on pre-existing knowledge of a local audience and does not take into consideration that both Czechs and the international visitors may come with rather different levels of knowledge of the country’s history.

The lack of contextualization also applies to the audio-visual material presented on the touchscreens. In the part of the exhibition dedicated to the culture of the 1950s and 1960s, visitors can watch short scenes from Czechoslovak films of that time. Once again, visitors do not learn anything more than the title of the film. For visitors who do not speak Czech, it is especially challenging to get any sense from these scenes – the videos are in the original sound without English subtitles. This is a pity especially in the case of the comedy The Fireman's Ball (1967) by Miloš Forman. By referencing Miloš Forman’s later work, the visitors from abroad could have learned that the director of the Oscar-winning-films like One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975) or Amadeus (1984) has his origins in Czechoslovakia and in the local cinematic new wave. This example demonstrates that a simple translation of the object description does not make the Czech content intelligible for a non-Czech audience.

Those who expect a clear storyline from an exhibition such as this will be disappointed. The sheer number of objects and the seemingly chaotic way of displaying them make it difficult to discern any common theme that would guide the visitor through twentieth-century Czech history. Instead, there are narrative fragments and sometimes strange narrative combinations. For example, a Soviet tank is used to depict not only the liberation of Prague by the Red Army in 1945, but also the occupation of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw-Pact troops in 1968. This kind of ‘narrative blending’ is not new in Czech discourse. In 2008, the Exhibition Hall Mánes presented a photo exhibition that juxtaposed the pictures of tanks taken in May 1945 and in August 1968. Back then, the curator of that exhibition Dana Kyndrová maintained that

[F]rom the historic point of view, the August occupation was basically determined by the events which took place at the end of WWII, the liberation of the majority of Czechoslovakia by the Soviet army. The exhibition places two seeming contradictions of our modern history next to each other – 1945 Liberation and 1968 Occupation – and offers the public a look at the presence of Soviet armies in our territories in a wider historical context. [10]

The exhibition makers at the National Museum seem to have agreed with this viewpoint.

In another installation, a highly controversial interpretation of Second World War and post-war events are presented: : three suitcases with personal belongings are inlaid into the floor, lying next to each other. The contents of these suitcases refer to the different groups of the Czechoslovak population who experienced expulsion or deportation between 1938 and 1946 – among them, the Czechs from the occupied borderland in 1938, the Czech-Jewish population during the war and the Czechoslovak Germans after 1945. Again, such juxtaposition of historical events suggests, especially in the case of the expelled Czechs and Germans, a very simplified interpretation that is based on the notion that the post-war events were merely an answer to the 1938 occupation. This is highly problematic especially with regard to the deportations of Czech Jews during German occupation. Indeed, the Holocaust – the extermination of approximately 263,000 Jews who had been living in the territory of the pre-war Czechoslovak Republic – is reduced to the information that local Jews were deported from Bohemia and Moravia. We do not learn anything about the tragic fate of Czech Jews in Nazi concentration camps, nor about the nearly complete extermination of the local Roma population.

A quite confusing interpretation of the Czech twentieth century can also be found in the bust hall. According to the introductory text, the busts “refer to the culture of memory and its changes in the power interpretation of history.” However, the line of busts from different time periods, made of different materials, does not really capture the dynamics of collective memory and forgetfulness: especially since the 3D glass portraits were created solely for the purposes of complementing the historical originals and, as the exhibition website states, to represent “personalities who did not get their own statue or bust, but who stood for important political currents, events or decisions.” As a result, traditional national heroes like the presidents Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk and Václav Havel are in the same line as the already-mentioned clero-fascist leader Jozef Tiso and the 1990s far-right politician Miroslav Sládek. There is no explanation as to what these personalities exactly stand for. Presenting the busts as symbols of various regimes could have been an interesting way to tell the story of the past century.[11]

The creation of the bust hall is even more paradoxical given the existence of a similar hall within the National Museum’s complex. The so-called “Pantheon” has been part of the historical building since it opened at the end of the nineteenth century and it presents the most important figures of Czech history. During the twentiethcentury, the Pantheon and its contents were repeatedly changed, especially after 1918, 1948 and 1989. A critical reflection about the removal or reinstallation of busts and statues, as suggested by the historian Kamil Činátl as early as 2010,[12] could have been a brilliant tool for demonstrating the key moments of the twentieth century which was supposedly the aim of the exhibition, History of the Twentieth Century.

Both reconstructing the largest Czech museum and preparing its future permanent exhibitions are certainly very challenging tasks. At the same time, such an extensive makeover provides a unique opportunity to reflect on the historical, contemporary and especially future role the museum might play in the public sphere. Unfortunately, the National Museum missed their chance to create an up-to-date historical exhibition that involves such elements of self-reflection. The Czech history of the twentieth century as represented in this exhibition does not offer any new visions of the past, it does not challenge the visitor’s historical thinking and it does not even attempt to tell a coherent narrative.

Several lessons can be learned from this: First, the attempt to show the richness of the museum’s collection can be counterproductive. Choosing one object with an interesting, and if possible, ambivalent story can say more than a glass display full of various objects. This can, together with well thought-out interactive elements, strengthen the educational function of the exhibition.

Second, there is a clear need to reconsider the historical role of the National Museum as an agent of the Czech national project and to redefine its mission in accordance with the challenges of the twenty-first century. This involves, among other things, opting for a more inclusive attitude, reflecting the diversity of contemporary Czech society and its international connections.

Third, the National Museum, as the central state museum, should not mediate solely comforting images of the past. Its desirable mission lies in triggering public discussions on controversial historical topics and in offering an intelligible story about the people of this country throughout the twentieth century.

On 27 October 2018, when the newly restored building of the National Museum was reopened, a video mapping entitled “Witness of History” was projected onto the reconstructed building, rendering it a huge screen. During the twentieth century, this monumental, historical building had truly witnessed key moments in the history of the country – from the declaration of independence in 1918, to the 1968 invasion, to the Velvet Revolution in 1989. In the twenty-first century, the National Museum should put more emphasis on its role as a witness. In a way, the institution should serve as a projection screen on which different visions of the past can merge together or coexist in one mosaic of common history.

Karolína Bukovská: (Re)construction of Czech History: The National Museum and its New Permanent Exhibition on the Twentieth Century. Cultures of History Forum (25.11.2021), DOI: 10.25626/0133.

Copyright (c) 2021 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editor.

Patrick Metzler · 21.12.2022

Localizing “Our Germans”: The New Permanent Exhibition in Ústí nad Labem

Read more

Veronika Pehe · 11.05.2022

‘The Nineties’ on TV: Remembering the Transformation Era in Czech Popular Culture

Read more

Jiří Smlsal · 25.01.2022

The Stench of Pigs and the Authority of Historians: Czech Debates About the Lety Concentration Camp

Read more

Veronika Pehe · 21.07.2021

Czech Prime Minister Implicated as Communist Secret Police Agent – Yet Nobody Cares

Read more

Jakub Vrba · 18.12.2020

Monumental Conflict: Controversies Surrounding the Removal of the Marshal Konev Statue in Prague

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).