31. Oct 2019 - DOI 10.25626/0105

Kata Bohus is a researcher at the Leibniz Institute for Jewish History and Culture–Simon Dubnow and specializes in the history of Eastern European Jewry during communism. She is also working as a curator at the Jewish Museum Frankfurt/Main where she is developing a new temporary exhibition on the history of Jews in postwar Europe. She received her doctorate from the Central European University in Budapest in 2014 and was a postdoctoral fellow at the Georg-August-University/Lichtenberg Kolleg in Göttingen between 2014 and 2016.

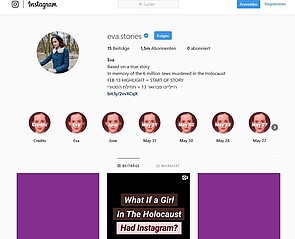

In 2019, on 2 May (the 27th of the month of Nisan), Israel’s annual Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Day was accompanied by a social media project on Instagram. Created by tech executive Mati Kochavi and his daughter Maya, eva.stories was based on the story of Éva Heyman, a Hungarian Holocaust victim.[1] The events of her lasts months are described in a diary attributed to Éva which was published by her mother shortly after the end of the war.[2] In a 24-hour period on 1 and 2 May 2019, Mati and Maya Kochavi posted a dramatised version of Éva’s life on Instagram in the form of a series of short video posts created with the social media site’s story function. The episodes were filmed as if Éva Heyman – played by young actress Mia Quiney – was documenting her life with a smartphone and uploading the videos on Instagram herself. In the manner of a tech-savvy twenty-first century Insta-user, the videos were adorned with emojis, and used internet lingo and hashtags.

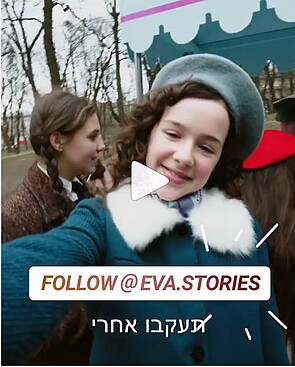

The project was accompanied by a poster campaign on the Ayalon highway just outside Tel Aviv: huge billboards featuring a hand clutching a mobile phone behind barbed wire. The official trailer advertising the series starts with the provocative question: “What if a girl in the Holocaust had Instagram?” Celebrities such as actress Gal Gadot and comedian Sarah Silverman urged people to follow Éva’s story, as did Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who posted a video message on his Twitter account with a link to the Instagram page. The project was very successful. Right after the first post, eva.stories reached 200 000 followers and by the end of the campaign, this number climbed to 1.7 million.[3]

However, the project had also caused considerable controversy even before the first post appeared online, with opinion pieces appearing around the globe from the New York Times to The Guardian. The most frequently voiced criticism was that eva.stories simplified the complexities of the Holocaust and trivialised its meaning, turning it into entertainment. Some argued that Instagram is an inappropriate platform for such content, as the Holocaust would appear “side by side to such nonsense, and such unnecessary and meaningless content … [which] can lead to this also being meaningless in some way."[4] One angry comment on the project’s Instagram page read, “This is genocide – not a PR project for Instagram.”[5] Others, however, saw potential in eva.stories. Israeli scholar Dr Noam Tirosh, for example, argued that,

the only question that needs to be asked in this context is the question of the message and not the medium. In other words, if Eva’s Instagram page is exploited to promote a one-dimensional, shallow narrative of the Holocaust, it is doomed to failure. By contrast, if it exploits the advantages that exist in Instagram to share complex messages about the Holocaust, its lessons and its significance for us today, it will be a resounding success.[6]

This article explores whether and in what way social media channels are suitable for sensitising young people to the topic of the Holocaust, its representation and memorialisation. More specifically, the text reflects on the quality of the eva.stories project in particular: its use of Éva Heyman’s story and the representation of the Holocaust in Hungary.

As far as Holocaust memory and representation are concerned, we are living through a time of transition. The last Holocaust survivors able to give first-hand accounts are passing away. The task of transmitting the memory of the Holocaust will soon fall to members of a new generation who did not experience the events directly. They are, however, digital natives who use smartphones as their main communication device and source of information. They are invariably only a few clicks away from accessing (and posting) information.

Given this level of digitisation, Holocaust educators and institutions tasked with representing the Holocaust are expected to go online and maintain a social media presence. This presence can potentially offer new possibilities for Holocaust representation that could prevent the memory of the event from becoming an empty ritual – or worse, disappear entirely. Social media can also help increase the younger generations’ participation in Holocaust commemoration by providing a space for debates that young adults are comfortable with and highlight the relationship between past and present. Indeed, Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem has its own Instagram account (@yadvashem) and regularly uses the stories function (wherein users post images and short videos that permanently disappear after 24 hours); the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum does so as well (@ushmm). Countless Jewish museums and concentration camp memorial sites use social media – most often Facebook and Twitter. Thus, the question whether social media can and should be used as a medium to represent and commemorate the Holocaust has been definitively answered in the affirmative.

However, the presence of the Holocaust as a topic on social media platforms has also raised new ethical questions about acceptable forms of representation. First, social media platforms are very democratic, since anyone can upload content themselves and comment on content created by others. This, however, also means that users can freely post anything they please, including antisemitic statements and Holocaust denial, which would appear alongside legitimate and informed sources of Holocaust education. Second, representations of the Holocaust on social media can potentially encourage questionable ethical conduct, as well as voyeurism, such as taking a smiling selfie at the gates of the Auschwitz memorial (or worse, in the former gas chambers) or taking pleasure from accessing the darkest and most private details of someone else’s suffering and death.

To address these ethical concerns, the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) has developed guidelines for using social media in Holocaust education. The organisation advises educators to keep general practice guidelines for social media in mind as well as offering a few specific instructions regarding Holocaust and genocide education: moderate the community, maintain privacy, connect trusted sources with common interests and agendas by posting links to their social media channels. The IHRA thus cautions against the use of de-humanising imagery, but considers appropriate vocabulary and historical accuracy essential when using a social media platform for Holocaust education.

Considering these ethical questions and guidelines, the eva.stories project can also be examined and evaluated as a tool for Holocaust education and commemoration.

"In the digital age, when the attention span is low but the thrill span is high, and given the dwindling number of survivors, it is imperative to find new models of testimony and memory," said Mati Kochavi in a press release about the eva.stories project. Maya Kochavi pointed out in an interview that Instagram made Éva’s story more relatable by using a medium that the younger generations are familiar with.[7] If we consider Instagram as a storytelling platform, it does indeed have similarities with Jewish wartime and post-war documentation practices. Many Jews across Europe kept diaries even under the most impossible circumstances, documented their lives in ghettos and camps – consider the famous Ringelblum archives from the Warsaw ghetto – and were the first to record both oral and written testimonies after the war. Instagram allows users to create their own stories, thereby allowing them to show and interpret events in their own way. Jews, in fact, showed remarkable strength and initiative in reclaiming this kind of agency in the immediate aftermath of the war and telling the story of the recent destruction from their own perspective. Thus, if paired with an awareness of the differences between the memory-based documentation of a testimony and the live recording of a smartphone camera, Instagram can be considered a reasonable choice as a model of Jewish testimony.

The producers of eva.stories disclosed that their main goal was to bring the Holocaust closer to young adolescents. “Studies we had done showed that interest in the Holocaust is starting to wane; in the rest of the world it almost doesn’t exist,” Mati Kochavi explained in an interview.[8] Indeed, recent studies conducted in the United States and Britain found “significant gaps in knowledge of the Holocaust,” especially among teenagers and young adults.[9] Though interest in and knowledge of the Holocaust are two very different things, the concern about the younger generations’ disengagement with the topic is valid.

Mati Kochavi and his team examined thirty diaries written during the Holocaust before settling on Éva Heyman’s story. Éva was born in 1931 in Oradea, Romania, into a Hungarian-speaking, upper-middle class Jewish family. Her mother, Ágnes Rácz was a pharmacist and her father Béla Heyman an architect. Her parents divorced when Éva was four years old, and Ágnes married the renowned Hungarian writer and publicist Béla Zsolt, with whom she moved to Budapest while Éva stayed behind with her grandparents and governess in Oradea. In 1940, Northern Transylvania – the area which included Éva’s hometown and had belonged to Hungary before 1919 – was reassigned from Romania to Hungary as a result of Nazi German arbitration. Hungarian jurisdiction meant the introduction of antisemitic legislation in the form of anti-Jewish laws that increasingly restricted Jewish rights and livelihoods. In the later stages of the Second World War, Hungary’s clumsy attempts to switch to the Allied side resulted in the German invasion of the country and the deportation and mass extermination of most of Hungarian Jewry. Éva’s mother and stepfather were visiting in Oradea (then called Nagyvárad in Hungarian) when the German invasion took place, and were trapped in the city. In May 1944, Éva was ghettoized with her grandparents, mother and stepfather. The latter two managed to escape the ghetto and survived the war. Éva and her grandparents, however, were deported to Auschwitz at the end of May 1944. The grandparents were killed immediately in the gas chambers and Éva a few months later, on 17 October 1944.

Éva’s mother Ágnes published Éva lányom. Napló [My daughter Éva. Diary] in 1947. The diary, written in first person, is an account about the war’s effects on a teenager’s life and about relationships between people in her family. The choice of eva.stories’ producers to base their project on that diary—especially if the goal was to look for an authentic account of an adolescent to whom today’s teenagers can relate to—is rather unlucky. From the moment the diary was published, it was unclear if the actual author was Éva Heyman or her journalist mother. Several historians have questioned the fact that Éva Heyman kept a diary at all and in 2016, the Hungarian historian Gergely Kunt convincingly proved that “judging by its style and format, Éva lányom could not have been written by a young adolescent.”[10] This means that the Kochavis’ Instagram interpretation of the story was based on another interpretation – by Éva’s mother – calling into question whether the project can be a legitimate tool to accurately inform about the actual experiences of a 13-year-old during the Holocaust. Nevertheless, it must be pointed out that the events described in Éva lányom did occur and that, even if the book is entirely the work of the mother, she was present to witness them.

The producers of eva.stories emphasised that Éva had wanted to become a photo-reporter and that, in a sense, they were fulfilling her dreams. That is, indeed, a very noble goal, but a close reading of the diary reveals that this career choice had much to do with childhood trauma, an aspect which remains unexplored in the Instagram story. The book starts with Éva’s thirteenth birthday, to which her mother – living elsewhere and having recently undergone an operation – does not show up.

Grandma says that Ági [Éva’s mother does not love anyone else but Uncle Béla (Ági’s new husband, Éva’s stepfather – K.B.), not even me. But I do not believe that. Maybe she did not love me when I was little, but she does love me now. Especially since I promised her to become a photo-reporter and marry an English Aryan.[11]

The diary suggests that Éva’s journalistic aspirations were at least partly the result of her need to get the attention and love of her mother, whose absence from Éva’s life was painful for the teenager. The goal of becoming a photo-reporter was a way to cope with this trauma and to channel her difficult relationship with her mother in a positive life goal. However, this central and very sad feature of Éva’s life is missing from the Instagram story which thus reduces the complexity of her personality.

The Instagram project is very much focused on the documentation of Éva’s present but the original text has many entries that reflect on the past. Perhaps the meddling with the timeline is the biggest weakness of the Instagram project, because it results in the confusion of the consequences of German invasion and local Hungarian anti-Semitism. For example, in the Instagram posts of 15 February 1944, cousin Martha is taken away from Éva’s birthday party—as we later learn—to be deported to Poland. But the real Márta was taken years earlier, in 1941. In July that year, the Hungarian authorities deported Jews living under their jurisdiction in Northern Transylvania who were not Hungarian citizens, or were undocumented. Márta’s father was not a Hungarian citizen and because the family did not want to be separated, they were all taken to an area in the Ukraine called Kamianets-Podilskyi, near the Polish border, which was under German occupation. There, they were killed in a massacre conducted by the SS.

Furthermore, in eva.stories, Eva introduces her grandfather’s pharmacy on 21 February 1944 with the words: “This is my grandpa’s pharmacy, my grandpa is the president of all the pharmacists.” A week later, on 2 March, we witness how the pharmacy is confiscated from the grandfather on “government orders”. Here again, events that had happened years earlier are presented as having taken place in 1944. According to the original Hungarian text of Éva lányom, Éva’s grandfather had by then been excluded from the leadership of several professional organisations of pharmacists in Nagyvárad, because he was Jewish and the confiscation of his pharmacy by the Hungarian authorities had already occurred in 1940.[12] Just like Márta’s deportation, the loss of the pharmacy was also the result of the Hungarian government’s antisemitic policies. However, the soldier assisting in the confiscation in the eva.stories scene is wearing a German uniform, with the Nazi eagle clearly visible on his sleeve. But even if the confiscation had occurred on 2 March 1944 (as opposed to four years earlier), no Nazi troops arrived in Nagyvárad until the end of that month, so it would have been conducted by Hungarians either way.

When the family is taken to the ghetto, shown in the last three posts on 5 May 1944 in eva.stories, the soldiers shoving the family onto the truck are again wearing German uniforms, SS insignia visible on their collars. The audible shouts in the background are also in German. However, the ghettoisation and deportation of the Jews of Nagyvárad was carried out by the Hungarian police and gendarmerie. The original text also makes this very clear and specifically highlights that only the driver of the truck that took the family to the ghetto was a German soldier: “The driver of the truck was a German soldier, I think SS, because he was wearing a black uniform.”[13]

Éva lányom contains detailed descriptions of the relations between Hungarians, Romanians and Jews in Oradea/Nagyvárad, revealing social tensions between these groups. For example, when the new Hungarian military administration deports Romanian families, Éva’s grandfather gets very upset over the injustice. A few days later, he is summoned to City Hall to the Hungarian military commander who informs him that "he could no longer be in the pharmacy because he is an untrustworthy Jew who likes Romanians."[14] The book thus also highlights Hungarian chauvinism and antisemitism in state bureaucracy and administration. The issue of widespread antisemitism among the Hungarian public and lower-level authorities also comes up several times in the original text, including when a Jewish hotel owner is arrested and robbed with the help of non-Jewish Hungarians.[15] The widespread usage of antisemitic language among Hungarian authorities is also a returning motif. When the police confiscates Éva’s bike, one of the policemen is quoted as saying that a “Jewish child is not entitled to a bike from now on, not even to bread, because Jews are taking away the bread from the soldiers.”[16]

These reflections on societal divisions and non-Jewish attitudes make the original text especially insightful regarding the everyday struggles experienced by the Jews of Nagyvárad under Hungarian jurisdiction during the Second World War. These sensitive details are, however, almost completely missing from the Instagram series. In fact, it never becomes clear where Eva lives; only in the very first post is there any reference to her nationality. From her wish to “one day, […] live in Budapest with my mama,” one might suspect that Eva is Hungarian. However, the fact that she lived in a town that had only recently belonged to Romania and then returned to Hungary thanks to Hitler, leading to various ethnic tensions, is not disclosed. Neither is the fact that Éva and her whole family experienced antisemitism on a daily basis not from the Germans but from the Hungarians. There are only two scenes in the entire series where one can directly learn about the attitude of non-Jews toward their Jewish neighbours: in the post on 21 February, a passer-by mutters “dirty Jew” at Eva; and during the German invasion scene ‘posted’ on 19 March, people are waving flags and clapping as German tanks slowly roll in. From this, the viewer understands that the non-Jewish population was unfriendly but does not receive any deeper insight into the ethnic divisions within the town or how Hungarian antisemitism affected the daily lives of Transylvanian Jews in general – and Éva Heyman in particular.

These seem like small details, but if we consider the eva.stories producer’s explicit claim regarding attention to historical accuracy and the guidelines of the IHRA, they call into question the nature of the project. Does eva.stories want to disseminate knowledge about the Holocaust or is it an artistic representation of certain events? Watching the story unfold on Instagram, one has the feeling that the elements of the project that are more artistic in nature are much more successful than those depicting the historical context. For example, the scene where a reluctant and emotional Eva is forced to put the yellow star onto her coat very convincingly highlights an adolescent’s point of view. “Everyone at school is gonna laugh at me!” – she screams at her mother and grandmother. This scene is not taken from the original text (which only briefly mentions the yellow star),[17] but is a fictional element of the Instagram project which successfully translates the consequences of racial antisemitic legislation into an everyday school situation. The original text of Éva lányom contains peculiarly few references to Éva’s inner emotional processes, though this is hardly surprising if we consider the text to be the product of her mother, who did not live with her daughter and thus likely had little grasp of Éva’s feelings. The eva.stories project manages to fill in these gaps with well-composed fictional scenes such as the one with the yellow star and the subtle exploitation of the technology of contemporary social media. When Eva is upset or scared, the phone shakes in her hand. When she is in an unexpected situation, her smartphone struggles to focus.

These features of the Instagram story project make it a successful artistic endeavour to convey the possible emotions evoked by the historical situation that Éva Heyman experienced. However, eva.stories fails to accurately depict said historical situation, calling into question the educational value of the project.

Social media, the main venue for social interaction and information-sharing among younger generations, cannot be ignored when it comes to Holocaust education and commemoration. Although it raises new ethical questions and practical issues, social media can be (and has already been) successfully used as a tool to disseminate knowledge. Instagram in particular, seen as a contemporary storytelling platform, shares certain attributes with Jewish documentation practices during the Second World War and in the immediate post-war period. It can thus be an exciting and innovative tool to present individual personal accounts to a contemporary, younger audience.

Focusing on the perspective of the victims is a vital part of Holocaust commemoration and education. The eva.stories project successfully presents elements of this perspective by using artistic tools to convey personal emotions. However, the dramatised re-enactment of the victims’ point of view carries in it the risk of denying social media users the chance to examine who exactly the perpetrators were, and thus why the Holocaust occurred. This is where the eva.stories project misses the mark. By failing to reflect on the antisemitism of the local non-Jewish population – so sensitively described in the original text of Éva lányom--and on the persecution of Jews by the Hungarian public administration even before the German occupation, the Instagram project does not allow users to examine the relevance of the Holocaust for contemporary society, where political radicalisation and the exploitation of xenophobic and racist ideas by political actors is a realistic and ever-present danger.

“Eva wanted to be a famous photographer in London, so we gave her a camera, let her tell her story on Instagram, and put up huge billboards in Tel Aviv,” producer Mati Kochavi said during an interview with Ha’aretz about the intentions behind the project. But we do not know what Éva would have shown if she had had access to Instagram and no living person on Earth is able to decide that for her. In fact, what the producers of eva.stories did was strip her of her agency: by deciding what parts of her story were important, they created their own version. That, in and of itself, would not even have been a problem, had they simply said so and framed the project as an artistic representation instead of a realistic (accurate) one. But the truth is, we will never know what exactly she would have shown us, "if a girl in the Holocaust had Instagram".

Kata Bohus: Éva on Insta: Holocaust Remembrance 2.0. In: Cultures of History Forum (31.10.2019), DOI: 10.25626/0105.

Copyright (c) 2019 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

![Author: unknown; Brandnewwta [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]](/fileadmin/_processed_/7/c/csm_Diary1b_4b567a4370.jpg)

Ágoston Berecz · 18.01.2021

The Trianon Ramp and the Obstinate Memory of a Magyar Greater Hungary

Read more

Katalin Madácsi-Laube · 28.06.2020

A New Era of Greatness: Hungary‘s New Core Curriculum

Read more

Emily Gioielli · 07.02.2020

From Crumbling Walls to the Fortress of Europe: Changing Commemoration of the ‘Pan-European Picnic’

Read more

János Gadó · 16.08.2019

The Splendour and the Misery of the House of Fates

Read more

Victoria Harms · 12.09.2017

Open Society v. Illiberal State: Europe, Hungary, and the ‘Lex CEU’

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).