18. Jan 2021 - DOI 10.25626/0124

Ágoston Berecz is a researcher at the Center for Advanced Study, Sofia and at Past, Inc, Budapest. He has previously been a Max Weber Fellow at EUI, Florence and New Europe College, Bucharest and has taught courses on the history of popular nationalism at Central European University and ELTE, Budapest. His current research focuses on language policies in Dualist Hungary and on the mass appeal of national movements in nineteenth-century Europe.

With the new Trianon monument situated across from the Budapest parliament that was inaugurated in August 2020, Viktor Orbán’s regime brings its thus-far backhanded flirtation with irredentist fantasies out into the open. Sporting the names of all the towns and villages of 1913 Hungary, the monument implicitly claims the entire expanse of pre-1920 Hungary for the agenda of “national solidarity” (the original Hungarian title is “Összetartozás”, which literally translates as “togetherness” or “belonging-together”, like the German zusammengehören). It also perpetuates a deeply entrenched golden-age narrative about a once Hungarian-speaking Greater Hungary by using the official names of the time, thus recycling the props that the advocates of an earlier version of the same narrative had inscribed in reality.

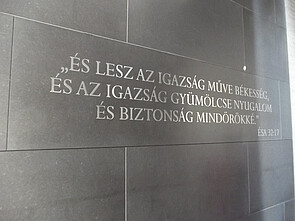

The memorial consists of a 100-metre-long ramp featuring the 12,000-odd names of localities carved on its two granite walls that lead down to what resembles the apse of a crypt, complete with a symbolic altar that visitors can walk around. The upright slabs of the altar, also made of black granite, are fractured to symbolize the body of the nation that has been torn apart; the slabs also enclose an eternal flame. The memorial occupies the carriageway at the mouth of Alkotmány utca, turning the latter into a dead-end street. With the choice of that location, the monument is widely feared to double as a roadblock, obstructing the way of future demonstrators from getting to the parliament square. In a scenario that Hungarians have become accustomed to, there was no public debate, and visuals were only released after the government had already ordered the installation of the memorial by way of decree (thus exempting it from all sorts of legal-procedural requirements). Even then, the authority that released the images had to denounce them when critics pointed out that the name of the Croatian capital showed up among the names listed (by including Croatia, it seems, they took it one step too far). It is certain, however, that the idea arose from within Orbán’s closest circle and that the government consulted the Institute of History of the Hungarian Academy of Science about which place names to use.[1] The inauguration, initially slated for June 2020, had to be delayed until August because of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The monument received mixed reviews in the segment of the media that is not controlled by the regime. Many applauded the understated design, a welcome contrast to the recent assault of the either rather “kitschy“ or „bombastic” sculptures on Budapest’s public places.[2] Some, including historians, also expressed sympathy for the cause.[3] At the same time, it was not lost on analysts how fraudulent it is to put the lands once governed from Budapest in the role of the victim or the martyr by making obvious references to the design of the Washington Vietnam Veterans Memorial and the Berlin Holocaust Memorial. In a charitable reading, the grief about the Trianon Treaty in official propaganda and the expansion of Orbán’s power in the neighbouring states merely aim at a cultural unification of ethnic Hungarians (Magyars) across state borders. Even that unsettling interpretation is hard to sustain once the Hungarian regime symbolically lays claim on large swathes of land without significant Magyar minorities. Critics also brought attention to the fact that thousands of the Hungarian place names that are central to the memorial’s message are artificial creations dating back to the Magyarizing frenzy around the year 1900.[4] As such, one impactful article, published under a pseudonym in the centre-right news portal Válasz Online, charged that the memorial represents a deliberate falsification of history. This article made a splash and, judging by some comments I overheard from visitors on the day of the inauguration, it hit a nerve beyond the regular readers of independent online media.

The 1900 census found Magyar local majorities in 4,718 out of the 12,686 settlements (37 per cent) included in the Kingdom of Hungary (excluding Croatia). In contrast, the rate of self-professed native Hungarians was below one per cent in 3,458 villages (27 per cent).[5] The predominant majority of non-Magyars did not speak Hungarian; in 1881, only 9.9 per cent of Slovaks and 5.7 per cent of the Romanians of Hungary claimed to speak it as a second language.[6] The number of non-native speakers steadily increased in subsequent censuses, although much of that growth is based on questionable data.[7] To zoom in on the more than 9,000 places annexed from Hungary in 1920, where the monument’s emphasis is placed, roughly 17 per cent of them registered Hungarian majorities in 1900.[8]

By the time of the Trianon Treaty was signed, there had been far more settlements among them with freshly Magyarized official names. More than 5,000 place names were altered at the turn of the century, slightly less than half of which were Magyarizations.[9] In some areas, particularly in Transylvania, recognizably Hungarian names had existed irrespective of the local tongue: these names either had their roots in earlier Hungarian-speaking dwellers or had been subsequently adapted to Hungarian, and they were upheld via Hungarian administration. For that reason, the newly fabricated names were very unevenly distributed, with a high concentration in areas where the previous Hungarian variants were simply the Slavic or Romanian names with Hungarian spelling. Thus, the nomenclature underwent a complete overhaul in some northern counties inhabited by Slovaks and in the Banat in the south (today, straddling Romania and Serbia).

According to the public ideology of the renaming process, the goal was to restore long forgotten or “distorted” Hungarian names. Not just the newspaper-reading public, but some of the inventors (i.e. government officials and experts) as well, had convinced themselves that they were reviving the former names and with them, were redressing an embattled history. They acted as if all settlements had been founded by Hungarian-speakers. In fact, in the eastern and south-eastern parts, only one-third of the place-name Magyarizations revived earlier forms, and such cases were very likely even fewer in the territory of today’s Slovakia. For good measure, the names of villages destroyed during the Ottoman wars were often used elsewhere, other than where they had actually been located; moreover, the new names were often selected quite arbitrarily out of a wide range of medieval variants.

The made-up, supposedly historical place names, mostly introduced between 1901 and 1912, represent a dual projection. Magyar nationalists of the late Habsburg or Dualist Era (1867–1918) projected the linguistically and culturally Magyar Hungary back to the past that they hoped to bring about in the present. They would spot the outlines of that happy state of things looming in any previous century, but they most often placed it in the Middle Ages – like Gusztáv Beksics, who described King Matthias’s fifteenth-century kingdom as a “Hungarian national state”.[10] The remote golden age was then separated from the sad but hopeful present by narratives of demographic decline and rebirth. The everyday discourse of Magyar nationalism, still very much of an elitist, gentlemanly character at the time, depicted non-Magyars as incidental, as strangers to their homeland and incompatible with a Magyar Hungary.

Repackaged for the post-Trianon era, the same tangle of historical imaginary continues to fascinate today’s Hungarians. The names contained in the 1913 gazetteer (a directory of place names and the immediate source for the monument’s list) acquired an aura of naturalness almost without controversy in the 1990s. They were chosen as the main variants in road and tourist maps of the surrounding countries, and they appeared in the last two original printed encyclopaedias in Hungarian, both of which devote a separate entry to each Hungarian settlement as of 1910. Owing to the prestige of such publications, the Hungarian Wikipedia, and later Google Maps, also adopted these made-up names. Meanwhile, for at least 25 years, the toponymy committee of the Hungarian government has worked to avoid homonymies with former Hungarian territories.

Lay historical narratives routinely inform the work of historians, too, but the transformation of the public sphere through social media has laid bare the gap between lay historical imagination and national historiographies. The tension between the two certainly existed earlier; but the narratives and emphases of history textbooks and popular history (aimed at a general audience) also trickled into public consciousness. Yet, popular history is losing against pseudo-scholarship, which has more desirable content to offer. The Orbán regime radically freed its memory politics from the burden of professional discourses, it scrapped even the semblance of trying to educate the public, and it let the national community enjoy itself. Indeed, by peddling in conspiracy theories and fake news, it reinforces the symbolic rebellion against the checks of civilization.

At the same time, and in a true populist vein, the current regime has not actually invented anything original. It simply latches on to a memory tradition that had already been favoured by its supporters. This tradition, in turn, continues the interpretation that the onetime Magyar elite had given to the events as it had to endure the downsizing of its dominion. Present-day Hungarians have partly inherited, partly consciously rediscovered this interwar framing of the ‘loss’ of Greater Hungary, which has been filtered through the prism of the Kádár Era and cross-fertilized with the narratives of Magyar minorities in the surrounding states.

While the revanchist propaganda of the interwar Horthy regime downplayed the non-Magyar majority of the lost territories, it did not try to deny it or to pretend that they were somehow Magyars. Most of its educated audience knew better. The propaganda even amplified such staples of imperial rhetoric as the theme of Magyar cultural supremacy over the minorities, by then mostly gone. In the long run, however, there has been no memory of Greater Hungary as an ‘empire’, for lack of a better term.[11] The programmatic ideology of Dualist Hungary’s leaders, who treated their country as a nation state and regarded its actual diversity as ephemeral, has kept sway over the Hungarian historical imagination. Today, the new monument only acknowledges the multi-national constitution of Greater Hungary on a plaque that is discreetly sunk into the pavement adjacent to the memorial; the plaque claims that the memorial is dedicated to the “memory of Saint Stephen’s Hungary, for a thousand years home to the Hungarian nation and the peoples cohabiting with it”. This plaque does not show up in the plans and is probably a half-hearted afterthought intended to obfuscate the main message.

During the Socialist period, the people who thought of themselves as members of the defeated ‘Christian middle class’ may have been the most likely to cultivate irredentist language in private and pass it on, but the emotional message of the flamboyant interwar propaganda had made a wider impact.[12] The Kádár era (1956–1988) expelled the memory of Greater Hungary into the ‘cold memory’ of book learning, with all its Magyars and non-Magyars. However, it also instilled a rigid nation state norm in people’s minds. Citizens of socialist Hungary, although socially incomparably more mobile than previous generations, overwhelmingly lived their daily lives with fellow Magyars. Thus, the monolingual nation state became their natural framework for envisioning the history curriculum; and historical movies, TV shows and novels also conjured up a monolingual milieu.

Very different was the experience of ethnic Hungarians in the surrounding states. There, the change of sovereignty became a myth of origin in private conversations, the significance of which would only grow with its recurrence during the Second World War, when Hungary briefly regained some lands that it had lost 20 years earlier. The events of 1918–20, to be sure, hardly caused a real break in most family histories. The bulk of the new minorities were peasants living in local, face-to-face communities, with tenuous attachments to the Hungarian state. However, their second-rank status ought to have hit them latest when their local worlds opened up and they became socialized into the anonymous community of minority ethnic Hungarians. From that vantage, the ‘old Hungarian world’, as they would call the times prior to 1918, came to appear in the structural place of the golden age, as the state of primeval innocence – while the interwar Horthy era often played the same role for the nationalist right in Hungary.

It is tempting to think that the memorial’s walls containing place names is primarily meant for Magyars from the neighbouring countries, as former politician Tamás Bauer suggested. Before the 2014 elections, Orbán extended the right to vote to these groups, for their loyalty (and their votes) seems to be the easiest to secure. Over the past century, the surrounding successor states of Dualist Hungary have engineered place names on a similar scale as the former Hungarian authorities (Romanian governments, for example, have introduced 730 to 740 freshly fabricated place names in the former Hungarian areas, as opposed to 670 to 680 prior name Magyarizations).[13] A disproportionate share of these name changes fell on Hungarian-speaking localities, deepening their inhabitants’ suspicion and hostility toward any place name in the state language. Ultimately, if this was part of Orbán’s calculations, engraving the 1913 gazetteer on the walls of the new monument may still not achieve its supposed goal. Twenty years ago, not only would it have given minority Magyars moral gratification to see their home places mixed with Hungarian settlements, but the Hungarian names alone would have acted as metaphors for freedom. Today, this magic seems to have worn out.

By the early 1990s, many people thought that irredentist nostalgia was on its way out. The opposite happened. The winds of 1989 brought the old right-wing community of memory back to life and in full splendour. People with a peasant background who had made careers under the socialist era joined others with actual ties to the old ruling class, thus completing a long process of fusion between peasantist and conservative nationalist traditions. It was this milieu that made a fetish out of mourning Trianon and gained an interpretive monopoly over questions of nation and national territory. Together with the memory industry catering to its needs, this milieu tied the two cultures of defeat – that of the former upper classes and that of Magyars in minority – into a potent victimhood narrative. National historiography aided this process with the way it framed its research questions.

In this memory culture, the ‘truncation of land’ in the Treaty of Trianon is the symbolic axis of the national space and a prominent hub organizing knowledge about the past. In other words, when recalling ‘historical Hungary’ or any fact predating 1918–20, the path of memory has to lead through Trianon. Better than previous alternatives, Trianon can embody the external force that prevents the nation from unfolding its essence – or, in Lacanian terms, Trianon can embody the Other that stole the nation’s collective pleasure. This Other enjoys the intimacy of the places engraved on the walls. The problem of the ‘stolen pleasure’ revolves around the question of the Other’s reality.

Since this Trianon-centred narrative appeared to be harmless domestically, the liberal elite preferred to look the other way as irredentist allusions gradually drifted into the mainstream. To some extent, this was justifiable – who wants to be accused of disregarding kin minorities, especially in the face of opportunistically wielded human rights arguments? As a result of the right-wing monopoly over all things national, then, respondents to two surveys in 2010 and 2013 already tended to accept the silhouette of the Hungarian Empire (complete with Croatia) as a symbol of today’s Hungary.

Victimhood narratives cannot afford to appear utterly cynical, and Trianon as a mobilizing trope can only avoid that by portraying pre-1919 Hungary as a nation state. This is the purpose of stifling the knowledge of the erstwhile non-Magyar majority (by making it a taboo, for example) in those circles where such knowledge exists. Normatively, the memory of territorial loss has long been yoked to the question of responsibility for Magyar minorities. The coupling of these two ideas then naturally gives rise to the overlaying of Magyar minorities onto the territories annexed a hundred years ago.[14] Respondents to a recent poll estimated the proportion of non-Magyars in Greater Hungary in 1920 at 31 per cent (median value), regardless of political self-identification. Those aged 18–29 and those with eight years of education or less guessed even lower (around 25 per cent).[15]

Focusing on the peace treaty narrows down the narrative to Magyars and retrospectively Magyarizes the land.[16] With the non-Magyar majority conveniently erased from sight, the dismantling of Dualist Hungary becomes an indefensible act of violence, by which Western powers trampled on their own ideals, and which only conspiracy theories can adequately explain. This operation finally allows the group to take pleasure in the role of the victim, without encountering considerable cognitive dissonance.

Or does it really? No doubt, the image of the ‘Hungarian language area’ – from a sufficient distance and in the right context – may be stretched to cover the mental map of Greater Hungary. Pars pro toto, the oft-reported Szeklerland becomes interchangeable with larger Transylvania, and most Hungarians believe that the majority of people living in today’s Arad and even Bratislava (10 per cent and 3 per cent ethnic Magyars, respectively) are Hungarian-speaking.[17] Meanwhile, Felvidék (‘the Uplands’), which referred to the Slovak-speaking northern counties in the late nineteenth century, has come to behave as an “authentic” label designating Slovakia from a Hungarian point of view and tacitly contesting its sovereignty.

But his internal polling machinery must show Orbán that even in the minds of his supporters the attraction of Greater Hungary becomes subordinated to the feeling of cosiness associated with the rump-Hungarian community that goes back to the Kádár era. What could be better proof of this than his first move (after dusting off the bulwark of the Christianity myth in 2015) to build a protective fence along the Trianon border? Aside from the rival self-image of the Kádár era, first-hand experience can also make it difficult to envision the former territory of the Kingdom of Hungary as Magyar. Passengers face this problem as soon as they try to order a coffee in Hungarian in a random bar in what they imagine to be Hungarian land. As a consequence, Hungarians alternate the two interpretive frameworks, one taken from the Kádár era, the other from the Horthy era, just as ancient Greeks were able to disregard their myths. The other side of the border can thus be Serbia, Romania or Hungary in an ideal sense – depending on the context and the situation. The relationship between the two visions is necessarily confused, as is Hungarians’ mental map of their ‘torn-away lands’.

The image of a Magyar – or almost Magyar – Greater Hungary is conjured up from similar ingredients and through similar operations that the Dualist Magyar elite used to envision its past. The passenger from Hungary, for example, will view the inhabitants of said lands as a mixture of intruders and Magyars in disguise, in unknown proportions. This is exactly the perspective of her precursors from a hundred years ago. What has changed is that it is now possible to project the national golden age to the Dualist Era. Over time, that is, the golden age has moved forward to the period that conceived it in the first place. Today’s ‘aliens’ beyond the borders may already appear to today’s traveller as a residue of the last hundred years. On the temporal map of autonomous historical imagination, the space claimed for the group has always been stripped of its familiar character in a time immediately preceding the span of living (communicative) memory.

Hungarian place names, including the fabricated ones, which capture the linguistic and historical ideals of the turn-of-the-century Magyar elite in an iconic form, are perhaps the most suitable tools imaginable to portray Greater Hungary as Magyar. Putting them in the role of victim, as the memorial does, is designed to compensate for the ‘stolen pleasure’. But the fairy castle of the new memorial does not simply transpose the past imagined at the turn of the century into today’s world. With the fictitious names, the former Magyarizing regime not only tried to rectify the past; it also marked the space at its disposal as a Magyar land for the future. For more cynical visitors, therefore, the memorial ramp may also mourn the bright national future that never came to pass.

Ágoston Berecz: The Trianon Ramp and the Obstinate Memory of a Magyar Greater Hungary. In: Cultures of History Forum (18.01.2021), DOI: 10.25626/0124.

Copyright (c) 2021 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

Katalin Madácsi-Laube · 28.06.2020

A New Era of Greatness: Hungary‘s New Core Curriculum

Read more

Emily Gioielli · 07.02.2020

From Crumbling Walls to the Fortress of Europe: Changing Commemoration of the ‘Pan-European Picnic’

Read more

Kata Bohus · 31.10.2019

Éva on Insta: Holocaust Remembrance 2.0

Read more

János Gadó · 16.08.2019

The Splendour and the Misery of the House of Fates

Read more

Victoria Harms · 12.09.2017

Open Society v. Illiberal State: Europe, Hungary, and the ‘Lex CEU’

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).