29. Apr 2018 - DOI 10.25626/0083

Dr. Emily Gioielli is an Assistant Professor, Adjunct of History and European Studies at the University of Cincinnati. Her research explores the role of women and gendered dynamics of (counter)revolution and political violence during the long World War One period in Hungary. She is currently working on a monograph entitled Home Front, Commune, and Counterrevolution: Women, Gender, and Political Violence in Central Europe's Long World War I, 1914-1925 and has begun work on a graphic history of the 1989 transitions in East Central Europe entitled Europe Throws a Picnic: The Paneuropean Picnic and the End of the Cold War. She is interested in the role of gender and (non)violence in regime change and the entanglement of social and international history.

Women and men experienced socialism differently. Yet, those who study the memorialization of the socialist period have emphasized the absence or marginalization of women’s narratives, the homogenization of victimhood and resistance, and the lack of gendered analysis in official narratives and exhibits of socialism and transition. Museums across the former communist region tend to subsume women under traditional categories, such as ‘political prisoner’ or ‘opposition’, and thereby overlook the gendered effects of communist regimes on the ‘private sphere’, and the ways in which this led to distinctive forms of gendered political resistance.[1]

There are, however, some rather effective interpretive strategies for integrating women’s experiences and drawing out the gender of socialism in museums and other publicly oriented contexts. In Germany, several museums on the history of everyday life (Alltagsgeschichte) in the GDR provide strong entry points for visitors to think about realms of action outside those they might typically associate with ‘politics’ such as shopping, consumption, fashion, etc.[2] Yet, in the case of the history of socialism, the challenge of balancing ‘how they lived?’ with ‘how the regime constrained how they lived’ has led some to criticize such exhibits as contributing to the fetishization of socialist material culture.

This article explores women and gendered experiences and memorialization of mobility and escape presented at two of the most popular tourist sites in Berlin: the permanent exhibitions at the Checkpoint Charlie Museum (formally called the Mauermuseum am Checkpoint Charlie) and at the Tränenpalast (Palace of Tears). The first exhibition of the Checkpoint Charlie Museum opened in 1963 in its present location, on Friedrichstraße on the western side of a former inner-German border checkpoint. The Tränenpalast exhibition opened in 2011 in the former departures hall on the eastern side of the border. It is maintained by the Stiftung Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (House of the German Federal Republic’s History Foundation). This essay pays special attention to how these exhibitions present women’s experiences of socialism and border crossing, and the roles that women and gender play in the interpretive frame of each museum. Grounded in the transnational and trans-bloc identity of Berlin, they offer an opportunity to compare old and new(er) exhibitions, and official and private memory sites. They also demonstrate the challenges of constructing a cohesive and inclusive narrative in a city and a country with divided histories and memories, one that was also the global symbol of Cold War bipolarity.

The Haus am Checkpoint Charlie (Mauermuseum) was established by Rainer Hildebrandt and opened in June 1963. It was located on the western side of the inner-German border crossing near the allied border crossing called “Checkpoint Charlie” by the allied forces. Only foreign tourists (not inclusive of BDR citizens), diplomats, and employees of the allied forces could use the checkpoint. This particular border crossing had become known internationally because of the unsuccessful escape attempt made by a young man named Peter Fechter, who was shot while attempting to flee the GDR and bled to death on the border because border guards on both sides refused to come to his aid.[3] The museum established at the checkpoint also became very popular with tourists almost immediately after its founding, and has remained one of the most visited museums in Berlin, despite the rising cost of admission, and the numerous other museums and monuments devoted to the history of the divided city.

During the Cold War, Hildebrandt was part of a political network which helped GDR citizens escape, and the museum was described as both a museum and resistance site.[4] It contains several permanent exhibits as well as temporary exhibitions and other resources. The exhibits on the Berlin Wall, escape, and resistance in the GDR are its most popular, though the museum also contains artefacts such as Gandhi’s sandals in its exhibition on non-violence.

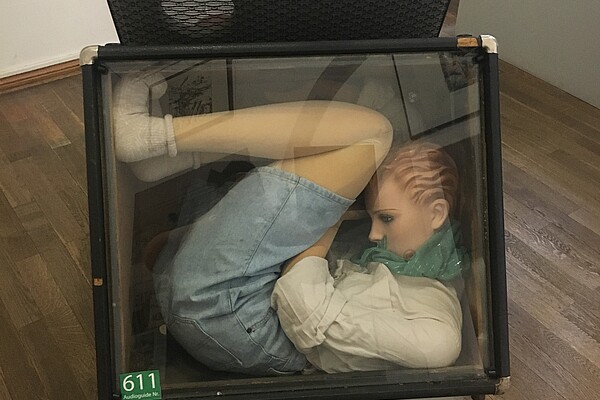

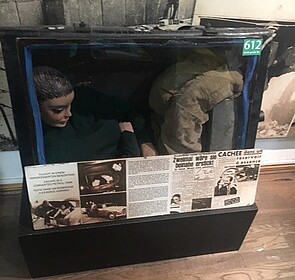

The focal point of the primary exhibits is: “The wall from 13th August 1961 to its fall”; “Berlin from front-line city to bridge of Europe”; “It happened at Checkpoint Charlie”; and “Inventive Escapes”. The latter is the most remembered part of the museum as it includes artefacts from the various improvised methods of escape. Visitors are met with a significant amount of text on nearly all the readily visible wall space as they enter the exhibition. Part of the outer wall follows large-scale geopolitical events, while the areas presenting artefacts, such as a car seat redesigned to create space for a young woman to escape undetected, or an aircraft, include short descriptions of dramatic escapes or attempted escapes.

However, this brief description overstates the level of organization of the exhibits on Berlin. While some label them as “charmingly improvised”, they lack any form of systematic organization, leading the viewer through what appears to be an arrangement following a stream of consciousness association of objects. In terms of contextualization, the exhibition maintains panels on broader macro-level events and anecdotes, while largely leaving out a meso-level description of conditions and policies in divided Germany, and specifically Berlin that would better orient the visitor. It also specifically puts forward a conceptualization of the eastern sector of the city as “hermetically sealed,” despite the museum’s location at a border crossing, and it relies on visitors entering the museum with an intuitive understanding of why people would seek escape from the communist East without providing the necessary or orderly explanation of local developments that led individuals to devise ingenious contraptions to leave.

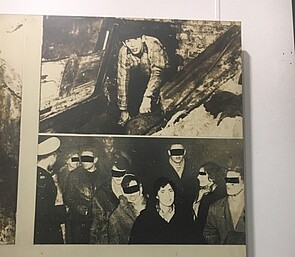

The museum’s exhibits on the Berlin Wall, and its public outreach, represent a victim-centred interpretation of history, and its emphasis on escape is intended to function as (re)construction of the terror that gripped East Berliners in divided Berlin. Yet, from a gendered perspective, its exploration of escape and a conceptualization of all those living in state socialist regimes as victims of the communist systems simultaneously homogenizes the experiences of GDR citizens and makes some people more visible as victims of the system. In other words, the focus on escape, and especially certain types of escape, privileges the experiences of men, who are overrepresented in this specific form of border crossing.

For example, one of the first artefacts is of a car with a seat designed to conceal a person from border control agents. The description explains that a young woman was smuggled out of Berlin in the car seat by her West German boyfriend. The thrust of the description is on romantic reunification, but it also positions the woman—the escapee—as a supporting actor in her own story. She hides and escapes, but it is her (Western) boyfriend who devises the escape plan. Similarly, the story of Peter Selle, told on one of the walls, recounts how, after having been separated from his wife, he planned her escape by going to East Berlin with an unsuspecting look-a-like girlfriend. He proceeded to steal the woman’s papers (abandoning her in the Eastern sector) and used them to get his wife out of the closed sector of the city. The story concludes with his serving a short prison term in West Germany in 1966 for the “deprivation of freedom” (of the young woman). However, the story is positioned within a narrative that highlights the lengths to which Selle went to reunite with his wife, while his wife plays no role in the story and the young woman is described as essentially having suffered no demonstrable hardship, despite the complaint filed by her parents, which led to his prison sentence. The man has the agency in this story: he devises the plan, carries it out, and suffers the consequences. Both the women in the story remain nameless, though not faceless—images of the young woman are presented. Selle is the hero who saves his wife from a life under communism.

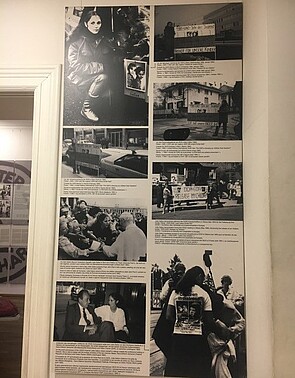

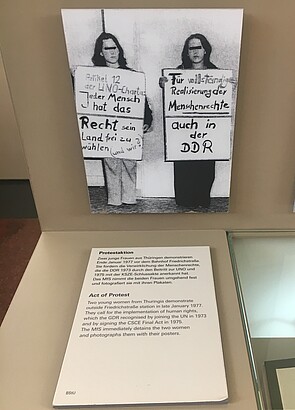

Throughout the museum women’s experiences are frequently presented either in relation to their relatives—especially fathers, husbands, or boyfriends—or in relation to their children. Sometimes this is how women themselves portrayed themselves, as reflected in the story of Annaliese Tanzer. She publicly sought permission to leave the GDR in order to join her children in the BDR, and the exhibit panel includes an image of her holding a sign. Tanzer was arrested and held for three days, but was eventually permitted to leave. Yet, on the whole, the exhibit displays women as objects of escape as opposed to subjects who act independently.

There are some notable exceptions to the overall representation of women, but even these tend to reinforce a central narrative of the heroic male escapee or rescuer. For example, panels on Jutta Gallus, a woman who was arrested attempting to escape East Germany through Romania and Yugoslavia and who spent time in prison, though she was eventually granted permission to leave the GDR despite having to leave behind her children, also emphasize the maternal connection as the focal point of her post-emigration activism. The panels depict her attempts to advocate for her children’s ability to join her in the BDR, including protests at Checkpoint Charlie and a hunger strike. Gallus and her two daughters were eventually reunited due to her protests and international pressure. In this case Gallus plays a central role in the exhibit, and the panels contain images of her protest signs and her reunification with her daughters. Yet, the exhibit transitions to a prominent discussion of Gerhard Löwenthal and a group called “The Call for Help from the Other Side”. The story of Jutta Gallus is dramatic, but in some ways it serves largely to showcase the activities of Löwenthal and the organization. The story is also not well connected to a panel on forced adoptions, which is relevant not because of the theme of motherhood, but because the panels on Gallus mention the institutionalization of her children. This exhibit design and organization is not particularly effective in helping the visitor understand Gallus’s experience, as well as the visa process (i.e. formally obtaining an exit visa), which often triggered enhanced surveillance and other forms of persecution.

Some of the problems of gender representation stem from the museum’s intentional approach to the history of the Wall: it does not really seek to educate or inform, but to evoke an emotional response, and the stories of escape recounted in panels throughout the museum are dramatic, brief, and digestible.[5] When read through the lens of an uncritical, Western European and American Cold War anti-communist perspective, one can almost immediately understand the meaning of the stories: the desire to escape communist oppression. Though the museum attempts to tell the story of the divided “front line” city, the thrust of the narrative is fairly clear from the beginning: the GDR is not a place where people wanted to live; it is a place people fled.

With regard to gender, the museum’s description of Berlin as a “front line” is especially apt given the reinforcement of a largely masculine, anti-communist narrative of ‘resistance’, which is emphasized not only in the exhibits pertaining to Berlin and Germany, but also in its other exhibits on Raoul Wallenberg (a Swedish diplomat who helped Hungarian Jews escape the Holocaust by issuing visas), non-violence, and the museum’s deceased founder, Hildebrandt. As Haliliuc notes in the case of Romania, the narrow definition of resistance activity and the emphasis on escape privileges the experiences of men and reinforces Cold War narratives that lionize the West and homogenize the experiences of all peoples who lived in state socialist Europe, who seemingly all experience socialism in the same ways and want the same thing.[6] Yet, even with its emphasis on escape and resistance, it’s clear that family, class, education, and gender played an important role in shaping people’s experiences of socialism and their capacity and desire to leave. Checkpoint Charlie’s historical purpose as the transit point for foreign tourists provides a useful context to understand the museum’s narrative, which tells a story of the communist East filtered through an uncritical western lens.

The permanent exhibition at the Tränenpalast (Palace of Tears), presents a far more nuanced, but also emotionally accessible interpretation of the local and social history of the inner-German border. The exhibition is located in the former departures area of the Friedrichstraße train station, one of the official border crossing points between East and West Berlin. Hundreds of people per day travelled across the inner-German border, and the building was given its name because it was where East and West Germans had to say their farewells. The museum is one of four sites supported by the Stiftung Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland.

A clear organizational structure helps guide the visitor through the history of border politics in the GDR, while interactive exhibits, such as a border window, and a model of the Friedrichstraße station, allow visitors to get a sense of how this border actually worked. Rather than a portrait of a “hermetically sealed” city, the exhibits show “everyday life in divided Germany”, while also contextualizing the limitations East Germans faced with regard to travel, economic activity, family life, and communication over the roughly thirty-year life of the Wall. It also positions the site within the longer history of Berlin, which allows the visitor to better grasp how the division of the city disrupted urban function and the nature of on-going connections between people living in both sides of the city.

The exhibition relies on an overall effective balance of artefacts (original and reproductions), film, audio, and text to guide the visitor through the history of border policies and both West and East German responses. It features discussions of East/West correspondence and parcels, which provide an opportunity to explore censorship. It also maintains the focus on persistent, though altered, interaction between the two Germanys, and the complex dynamics of separated families. The exhibits feature stories of escape, as well as discussion of de-naturalization for GDR citizens who were forced to leave or were unable to return because of activities regarded as dangerous to the state.

Like the Checkpoint Charlie Museum, the Tränenpalast covers a lot of ground. Yet the structure of the museum and the altogether more effective contextualization of themes provide a much more nuanced portrait of the history of the inner-German border and the way it (re)shaped people’s lives on both sides of the Cold War divide. It also provides a more sophisticated picture of how the GDR used the border regime to eliminate dissent in the East and cultivate anti-Western sentiment, for example, by shielding members of the Red Army Fraktion. These explorations, especially the issue of de-naturalization, make the Tränenpalast a key site through which to examine a far different form of resistance than that offered by the Checkpoint Charlie Museum.

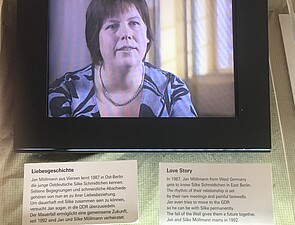

Just as the Tränenpalast generally provides a more nuanced narrative of divided Berlin, its inclusion of women and representation of gender relations is also more complex than that of the Checkpoint Charlie Museum. For example, the museum maintains a section on the theme of “Families Separated by the Wall” which includes a discussion of the flow of packages from west to east as well as letters between the two sides. Rather than place the emphasis on methods of escape, it addresses why people left and/or how they coped with separation, and the implications of these persistent communications, including surveillance, etc. Not only does this feature more examples of women’s experiences, it also gives them more agency. For example, one of the artefacts is accompanied by the explanation that its owner, a woman named Erika Wekel, left because she was unable to take her graduation exams due to her father’s occupation. This puts emphasis on why she wanted/needed to leave—because of the loss of opportunity—rather than on the act of escape. In doing so, this segment on Erika Wekel gives the visitor an insight into different forms of persecution—loss of educational and occupational opportunities—and individual experiences of socialism that were shaped, in this case, by the religious identity of Wekel and her family. Likewise, in a letter in the binder of additional letters included in the exhibit, a visitor can read about the experience of a woman named Edith K. who escaped at a crossing point and left her young daughter with her parents. She eventually lost custody of the child to her parents as she was unable to reunite physically with her daughter (or that is the implication), but she maintained correspondence with her. Again the emphasis of the story is not on the escape itself, but rather on the meaning of the escape, and the various ways the state could pressure their citizens by using families as pawns.

Like the Checkpoint Charlie Museum, the Tränenpalast also explores the theme of political activism within the GDR and especially how it relates to crossing borders, in particular the smuggling of information. Yet, in terms of gender representation, the latter exhibition presents a more collaborative and broader conceptualization of resistance that makes visible the contributions of women—including married women—outside of their role as mothers. For example, an image of a woman and man packing up large boxes is accompanied with an explanation that married couple Reinhard and Bärbel Klaus decided to leave the GDR in May 1989 as a result of constant harassment. They pack up their belongings and send them westward, but Bärbel also smuggles slides of environmental damage in her glasses case. This presents Bärbel as an active participant in the decision to emigrate and in resistance activities. Likewise, in the exhibit of suitcases containing artefacts and stories of people who crossed the inner-German border that stands in the centre of the hall, individual stories of escape and emigration are presented in ways that either emphasize the mutuality of decisions to leave as families, or the agency of women themselves. Men and women, mothers and fathers make decisions and act together to emigrate or escape for all different sorts of reasons, and in many cases, these reasons are explicit. This helps the visitor better understand the nature of the challenges that citizens of the GDR faced, whether economic, political, or personal.

The interpretive threads of the Wall exhibits at the Checkpoint Charlie Museum and the Tränenpalast are clearly different. The former homogenizes GDR citizens as victims of an oppressive regime and highlights the role of westerners—Germans or others, but especially Rainer Hildebrandt and his friends—in resisting and helping save people from the oppressive regime. Although it addresses a number of themes, the thrust of the museum, and indeed its continuing appeal to tourists, is on the harrowing stories and homemade methods of escape. This emphasis, and the way that the exhibition frames such stories, highlights the agency and subjectivity of men, while generally relegating women to the side lines of stories or reducing them to roles as daughters, girlfriends or wives, and mothers. There are notable exceptions, such as the story of Jutta Gallus, but the organization of exhibits does not do a good job of helping the visitor gain the knowledge necessary to fully understand her experience. It also does not stand alone. Rather, it seems to serve as an entryway into the description of a western aid organization.

The Tränenpalast addresses similar themes as the Checkpoint Charlie Museum, notably the border. However, the interpretive thread in this museum places emphasis on a shared history of division. It is far more systematic in its approach to explaining the border regime—and how it changed over time, and in guiding visitors through this history. On the whole, artefacts and explanations of them do a better job of helping visitors understand the varieties of experience that shaped the lives of people on both sides of the inner-German border. The Tränenpalast mostly avoids reproducing orientalizing narratives of the socialist space by explaining the varieties of experience inside. The emphasis on a shared past applies to the museum’s representation of women and gender relations.

Women featured in the exhibition are generally presented in ways that more effectively highlight their agency: they take decisions, they plan escapes, they are activists; their voices—quite literally—are included. Explanations help the visitor understand how gender and women’s roles shaped their experiences of socialism. If anything, the exhibits illuminate women in non-traditional ways, showing emigration and/or escape as a process of negotiation and mutual decision-making, especially between husbands and wives, and also showing that women were willing to emigrate, even though it sometimes meant relinquishing their children to family members who stayed behind. Through more effective explanatory material, the Tränenpalast allows the visitor to glimpse the highly varied experiences of socialism and the border regime, as opposed to leaving the visitor to conclude that a widespread hatred of communism led people to emigrate through both official channels and by escaping.

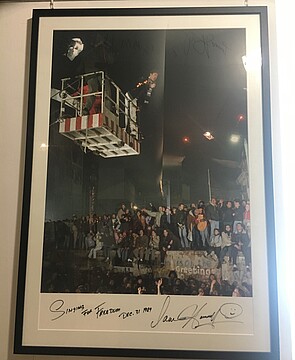

Both museums about the Wall are able to provide the visitor with an emotional experience, and I would argue that the Tränenpalast does a better job of giving the visitor even a small glimpse into the frustrating process of crossing the border. Yet, in thinking about these museums as opportunities to teach the history of the Cold War, in some ways it seems to me that the Checkpoint Charlie Museum better reflects the actual ways that people remember, and transmit the memory of, the Cold War: in disorganized snippets of macro-level developments and dramatic, singular examples of escape, which end with Ronald Reagan, Pope John Paul II, and David Hasselhoff (an autographed picture of his 1989 concert in Berlin). Dislodging this enduring narrative or at the very least making it more complex and inclusive of different groups’ experiences will be very difficult indeed, but as the Tränenpalast shows, it is possible to speak both to the heads and hearts of visitors who flock to once-divided Berlin.

Emily Gioielli: Displaying Gendered Experiences of Socialism and Escape: The Checkpoint Charlie Museum and Tränenpalast. In: Cultures of History Forum (29.04.2018), DOI:10.25626/0083.

Copyright (c) 2018 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

Hans Gutbrod · 30.05.2023

Sebald's Path in Wertach -- Commemorating the Commemorator

Read more

Matěj Spurný · 31.10.2021

The Colour of Compromise: The 'Documentation Centre for Displacement, Expulsion, Reconciliation' as ...

Read more

James Krapfl and Andrew Kloiber · 28.05.2020

The Revolution Continues: Memories of 1989 and the Defence of Democracy in Germany, the Czech Republ...

Read more

Sabine Volk · 11.03.2020

Commemoration at the Extremes: A Field Report from Dresden 2020

Read more

Gespräch · 30.11.2019

"In Auschwitz hat sich die Wirklichkeit entlarvt" - ein Gespräch mit Daniel Kehlmann

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).