21. Jun 2018 - DOI 10.25626/0085

Ondřej Táborský is a historian and curator at the Department of Modern Czech History of the National Museum in Prague where he (co-)authored a number of smaller and larger exhibitions (Red Museums 2011, The Second Life of the Hussite Movement 2016, Retro 2016). His current research focuses on the Czechoslovak consumer society during Communism. He is leading investigator of a three-year research project Consumer Imagination of the Communist Dictatorship. Czechoslovak Advertisement in the Post-war Era.

Today, we are witnessing a situation where European regional museums and art galleries, much more than centralized national institutions, are facing the challenge of finding a new mission for themselves. The majority of them were founded in the nineteenth century as symbolical representations of the bourgeoisie or as tools for raising the consciousness of national groups. The impact of globalization in cultural production and the growing competition from new media have clouded the museums’ purposes. Moreover, public demands to link their educational functions with a mission to forge regional identity are also significant. Finally, regional museums are faced with the challenge of integrating their offerings into a network of competing tourist attractions.

In light of these problems and challenges, Silesia might seem like an ideal laboratory for museums, being a region that spans across three nation-state borders; that was dissected many times by shifting borders, and thus provides a space for both, fusion of and conflict between nationalities. Throughout its history, Silesia has been a multi-national place. Once part of the Hapsburg Empire, then mostly Germany, today its larger parts belong to Poland, while small bits are located in the Czech Republic and in (East) Germany. Also geographically, this is not a well-defined area. Covered in mountains and valleys, it extends over fairly great distances. Its territory is too big to be united in one folkloristic identity. Precisely because of this diversity we find so many different perceptions of Silesia in the three countries that it spans today. In Germany, the term Silesia is no more than an imaginary land, a memory of a limb amputated from the national body. In the Czech Republic, it belongs to the official identity of the state, but to many citizens it is unknown, or regarded as something pasted on to the border with the Polish neighbors. The question of Silesian identity is perhaps most acutely felt in Poland, where it is viewed with ambivalence.[1]

Every country has its own Silesian museum, the mission of which is to somehow define the regional identity with its instable boundaries. This review of the regional museums in Görlitz (Germany), Katowice (Poland) and Opava (Czech Republic) is meant to show how the museums present the region’s shared past to express Silesian identity and to what extent they have adapted themselves to contemporary trends in museums.

The core exhibition in the Silesian Museum in Görlitz is the oldest of the three museums compared here. The museum opened in May 2006 after more than thirty years of efforts to establish an independent institution and after spending five years in provisional quarters.[2] It is no surprise that the history of this museum influences its exhibits in many ways. It was originally founded in the 1970s in West Germany as a place for preserving the memories of those Germans who were expelled from Polish Silesia after the Second World War. It was completed after the fall of communism and the subsequent reunification of Germany. The museum was eventually moved from Hildesheim in Lower Saxony to Görlitz in Upper Lusatia. The reason for choosing Görlitz as the new location lays in the fact that the town was part of Silesia after 1815 and it borders on today’s Polish Voivodship of Lower Silesia. The museum was part of an attempt to create a cultural center that would contribute to forging an identity in a region that is undergoing a difficult socioeconomic transformation after the fall of communism and Germany’s reunification. The initial influence of German expellees’ organizations on the museum has gradually decreased under the weight of German reunification plans and local interests. The museum’s exhibits reflect all the interlocking interests resulting in a relatively daring mixture of pro-European ideas characteristic of the national cultural politics, attempts to create a local identity that can attract tourists, and the remaining, still-potent memories of the expellees.

The location of the museum in Görlitz’s renaissance Palace Schönhof, joined with two other buildings, determines the flow of the museum’s story of Silesian history. To begin, visitors must enter the second story of the first building, where they encounter the basic determinants of Silesian history and identity. Various displays and infographics present the themes of transportation, industry and trade. For a symbolic introduction to the history of Silesia, there are objects chosen for their representativeness—models of riverboats, statues of miners, maps, and porcelain bearing the arms of various towns. Displayed here, for example, are Wrocław as a metropole and Krakonoš/Rübezahl as a symbol of the dominant mountains and borders of the region. A smaller side gallery presents the story of the town of Görlitz and its surroundings, as an element integrated into Silesia in the nineteenth century. From the start it is obvious that for the authors of the Görlitz exhibition Silesian identity means the identity of the German speaking population even though the Polish history of the region is also included in the narrative.

The most ancient history is told by a grouping of traditional elements of a didactic exhibition—the colonization in the Middle Ages, religious life, handicrafts and the life of the aristocracy. These are presented in floor-to-ceiling glass cases combining gallery-style arrangements with niches surrounded by images, text and infographics. Certainly worthy of interest are also the restored painted ceilings and an artful arrangement of small objects in displays that entirely fill another room.

The flow of the exhibition’s story is interrupted by a space where the presented artifacts are left to speak for themselves. Objects are arranged in dramatically lighted displays in a darkened room. Their narration can be heard via an audio guide. The stories and the objects are well-selected, so that they not only represent all eras, the different social classes (aristocrats, artists, entrepreneurs), and the land itself (mountains and towns). They also document a diachronic and synchronous narrative (the story of an artifact both over the centuries and frozen in one time). Moreover, they excellently combine a snapshot of individual and structural events, and changes in the societal roles of their former owners (e.g., the coat of a once wealthy farmer, later expelled to Germany). The story of how Silesia passed in the eighteenth century from being a part of the Habsburg Empire to being a valuable possession of the Prussian state is presented on the first floor in a similar form of display as in the previous rooms.

To continue, the visitor must move to the neighboring building through a glassed-in courtyard, which serves as a research center. There, on the first floor, the history of Silesia in the nineteenth century is animated in chrono-thematic installations. In the true spirit of German historical social science, the curators give attention to the life of the nobility, the revolutionary year of 1848 and industrialization. In the next, elongated room are two horizontal cases and one large vertical case that trace the development of local tourism through maps and souvenirs.

One floor above, as in the neighboring building, the flow of history is interrupted, this time by a room dedicated to art. Given the limited space, and because the most valuable art of Silesia is now located in Poland, the curators have chosen to concentrate on landscapes, art schools, architecture and exhibitions.

On the top floor, the museum presents the fate of the region and its inhabitants from the First World War to the advent of Nazism. In accordance with the layout of the room (with wooden columns and a staircase in the middle), the story is presented in a circular track, combining both vertical and counter-top displays. Even though the entire room is devoted to this one short period of history, the chronological presentation seems rather terse, considering the thematic richness of the subject matter. Besides the turbulent 1921 plebiscite to decide the national borders that divided up Silesia between Poland and Germany, the visitor’s attention is drawn to literary life, daily activities, traditions and dialects.

Toward the end of the exhibition, the visitor must return to the ground floor, where the Nazi and communist dictatorships are presented in one large room. The narrative of pre-1945 development is based on a description of structural changes, persecutions and selected life stories of famous Silesians. The postwar history is presented mostly as a story of expellee institutions and of Silesia as part of the Polish territory. But in contrast to the previous rooms, this area is focused on the memories of various individuals caught up in the mechanisms of power used by both the Nazi and communist regimes. In this part, like in other sections, the history of Silesians from the Czech lands is completely omitted. The exhibition ends without any anti-Polish resentment. Its underlying mission is clearly based on the Christian idea of reconciliation of nations which in the exhibition itself culminates with the year 1989.

The Silesian Museum in Katowice sees itself in the tradition of its predecessor that was founded in 1929. That first institution had been conceived as a purely Polish institution aimed at showing the "Polish character" of Upper Silesia after it became part of the newly founded Polish state. The earlier museum was abolished at the outbreak of the Second World War, and its rebirth had to wait until 1984.[3] After years of being in a former hotel, the regional and national governments decided to build a new, representative building that reflects the importance of Silesia and the unique identity of its local inhabitants.

The new museum, which opened in May 2015, is located quite symbolically on the site of the former Katowice coal mine, which ceased operations in 1999. This choice of location corresponds to similar attempts to preserve and re-imagine the function of a monument to industrial culture in Vitkovice in the nearby Czech city of Ostrava and in the German Ruhrgebiet. In the Polish case, an attempt was made to establish a comprehensive cultural center with greater than regional importance. A building for the symphony orchestra, a newly built congress center, and the Spodek sports complex, a well-known feature of Katowice, are adjacent to the museum’s space. Other former industrial buildings in the area have also been refurbished for cultural purposes.

The museum building, designed by the Austrian architectural firm Riegler Riewe Architekten, is placed underground. The historical exhibits are found at the very bottom of the structure. The first below-ground floor is dedicated to Polish art, represented by a selection of nineteenth and early twentieth century art, postwar trends and examples of the non-professional art style. This part is based on remnants of the collections of the original museum which was built as symbolical representation of Polishness. On the floor below, next to the historical exhibits, is a small collection of sacred art from Silesia and a permanent exhibit about Polish theatrical productions. A well-designed area in a separate hall houses temporary exhibitions.

Gates into the mineshafts form the entryway into the historical exhibits, entitled "The Light of History: Upper Silesia throughout History". They include miners’ clothing and audio-visuals of miners entering the mine. However, immediately after this symbolic beginning, the visitor enters space dedicated to the beginnings of Silesian history.[4] In an oval room, dominated by a replica of the rotunda in Czieszyn, the roots of Silesian identity are displayed in the form of a library of digitalized versions of old publications about Silesia. Beyond that, there follows a somewhat sparsely furnished imitation of a nobleman’s salon, with projected images of actors dressed in baroque costumes. The intention of this room is to illustrate the life of the nobility, the rural economy and the origins of the mining industry.

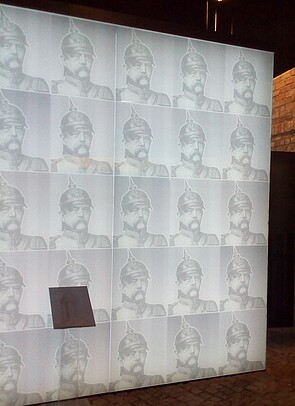

The curators present the rise of industrialization with striking audio accompaniment in the form of the sound of blast furnaces. Then there is a short half-diorama of figures in a coffeehouse, accompanied by voices evoking the linguistic diversity of Upper Silesia. After a passage that clearly aims more at evoking emotions than providing information, a part with rich infographics follows, dedicated to the urbanization of the region and relations between its nationalities. A symbolic emphasis on the importance of religion and language to Polish identity in the German Reich is presented by a glass chapel covered on the outside in German writing and a portrait of Bismarck, which contains a collection of prayer-books.[5]

The narrative flow is interrupted by scenes from everyday life: an Upper Silesian wedding, the recreation of home life, and a local musical production. As in the area devoted to the nobility, the curators use video clips featuring contemporary actors portraying the life at the time.

The presentation of the peaceful aspects of the Upper Silesian identity ends with a passage devoted to the First World War, the plebiscite and three Silesian uprisings at the time. A replica of a city street (a very common feature in contemporary Polish museums) illustrates their impact on the region. The story is divided into its Polish and German versions, personified by the fate of one nationalist from each camp, Carl Ulitzka and Wojciech Korfanty. This part of the exhibition, the most reliant on text-filled panels, seems like a diversion from the narrative style of the other exhibits; a collection of objects from everyday German life is installed in cases along the walls, serving as symbols of the German identity.

The events of the war are repeatedly presented in narrative fashion which evokes obvious comparison with other Polish museums. The white-clad figure of a bureaucrat in his office leads into a darkened room with official proclamations, propaganda posters and a guillotine, an intentional evocation of the peak of terror. After sections featuring expulsions of the German population and resettlement of Polish citizens from lost Eastern territories, with a replica of a workers’ dormitory, the museum offers considerable space for everyday life under the communist dictatorship, represented by a symbolic tenement and three living rooms from different periods. The central exhibit in the hall is a Polish Fiat 126p, nicknamed the maluch (baby). Another part of the exposition explains two crises at the time, ecological and economic, with the help of text and infographics.

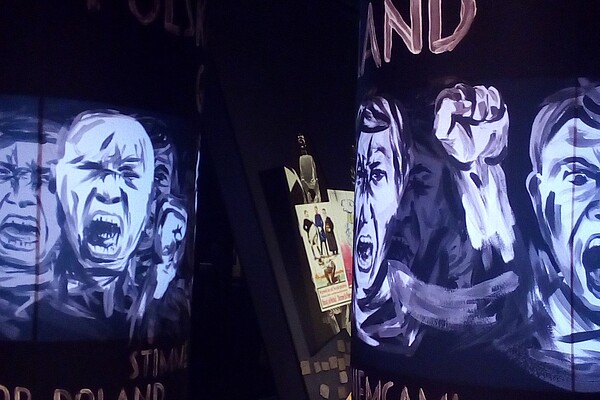

The part of the museum where the story of the Solidarność and the atmosphere of martial law is told, uses a sophisticated cinematic style with mannequins, audio, and video installations, and can be considered the culmination of the exhibition. Personal recollections, displayed on a wall, may be intended to diffuse any possible nostalgia for the time of the communist dictatorship, or perhaps as an attempt to show respect for and reconciliation with those people who suffered from post-1989 economic changes. The exposition ends with a display of one of the micro-processors manufactured in Bytom, begging the question of how Upper Silesia will move forward without the heavy industry that characterized its economy for so many decades.

Of the three museums, the one in Opava is not only the oldest, but also the one that most approximates the traditional ideal of a museum. The museum building dates from the 1890s, and it represents a non-linear story of two hundred years of the rise, fall, renewal and unification of the cultural institutions of two nationalities, Czech and German, who once inhabited this town. Its fusion into a comprehensive unit makes the Opava museum an institution of more than regional repute, even though the town itself is eclipsed in importance by the neighboring Ostrava-Karvina conurbation.

The collections of the Silesian Museum consist primarily of natural and historical artifacts, which in themselves dictate the Museum’s mission to a certain extent. New exhibitions began to be prepared in the second half of 2009 and opened during 2010–2012.[6] The curators decided on a dynamic presentation of non-chronological themes that seem like extracts from an encyclopedia of Czech Silesia.[7] The exhibition consists of installations in display cases with a minimum of dioramas, containing a mixture of aural objects in combination with remnants of material culture offering historical and anthropological perspective. Structurally, the central exhibits of the Opava museum take after the Czech national museum in that they are divided into sections for the natural sciences and history.

The first part of the museum, located in the basement of the main building, focuses on nature in Czech Silesia, with traditional displays. Despite the old-fashioned installation form, this passage is impressive, thanks to an interesting combination of glass cases and the original brick masonry. As mentioned before, dioramas are avoided in favor of the considered use of graphics and audiovisuals.

Originally, there was an exhibit on the ground floor of the building called Wings of Thought that was focused on the intellectual life of the nineteenth century, drawing upon the collections of the museum, most of which come from that century. In the Fall of 2017, the exhibition was replaced by an exhibition about the Silesian poet Petr Bezruč. The reason for this change is not clear. The heart of the Opava museum core exhibition called The Silesian Encyclopedia presents all periods from the stone age to the present in an anthropological approach. Various themes mostly from the history of Czech Silesia, such as the church, mining, death, languages, trade, and so on are exhibited in the individual displays. A section called The History of Silesia used to be part of the exhibit, located in a purpose-built gallery. It used symbolic objects from the history of Silesia to present the region and its relationship to the Czech state. At the time of this author’s last visit to the museum in autumn 2017, this part of the exhibition was undergoing reconstruction. From the changes that took place in the short time after their opening, it seems that the exhibitions of the Silesian Museum in Opava are as mutable as the Silesian identity.

This short review of the three museums on Görlitz, Katowice and Opava has shown that each one of them approaches the issue of the identity of Silesia from a different perspective. Their themes are nevertheless dissimilar, as are the techniques with which they animate them.

The museum in Katowice takes not only its format (a “narrative museum”) but also its modes of presentation (streetscapes, talking figurines) from current fads in Polish museums. Its exhibition is a spectacle and aims to combine entertainment with education. The predominantly cinematic presentation leads, however, to a demotion of the objects’ actual importance and to the promotion of a particular storyline. Of course, this adds a certain tension or cinematic experience that is always popular with less demanding museum visitors. However, there are many disadvantages to such an approach. The Katowice museum has drawn a wave of criticism since its opening, accusing it of reductionism, of resigning itself to the presentation of material culture, and even of distrust in the visitor’s ability to come to his or her own conclusions.[8]

In many ways, it is possible to view the Katowice exhibition as very manipulative, because it chooses to present only certain historical periods and themes. This is true from the very beginning of the exhibition, where most of the older history is lumped into one large and one small room. The history itself in the Katowice exhibition begins with the rise of industry, which leads to the perception that history is only what is dynamic. Moreover, like the movies, it puts emphasis on conflict and antagonism. Religion is limited by the curators to a struggle for the preservation of Polish identity. They do not see it as a means for contemplation, spirituality or fantasy. The culture of the fin de siècle is reduced to café society, pub bands, and home cooking, as if all other spheres of human activity had died out in Silesia. The nationalities question is seen solely from a viewpoint of conflict, with the obvious intention of incorporating it into the official state narrative. For this reason, traces of what could be seen as Silesian identity, represented for example by leaflets about local customs and an audio guide in Silesian language, serve more as an ornament than as the main narrative thread. The presentation of a more simplified history in the Katowice museum may be more entertaining than the ones in Opava and Görlitz, but it also is less useful for serving the educational purposes of a museum.

The exhibition in Opava in many ways can be considered the antithesis of the one in Katowice. Its main purpose is to educate, while entertainment is pushed to the background. Because it is structured as a freely changeable puzzle without a unifying narrative, it lacks a strong emotional impact. What may add to this is the rather cold scientific appearance of the exhibition, without any tension or surprises, or any appreciable political connotations. Except for occasional mentions, issues of nationality, religion and social class are absent. Thanks to that, the museum does not evoke any controversies akin to the Katowice museum, but neither does it provoke discussion, and in that respect it has little potential for the formation of a Silesian identity. Its basic structure is like a game that in its openness invites the visitor to play. As a result, Silesia is presented on a highly abstract level without any anchoring in the present.

This concept is rather original, but for its didactic approach to the presentation of the past to be effective, it would require better cultural infrastructure in the form of detailed audio guides, interactive exhibits, programs for the public and a sophisticated museum shop. The apparent intention of the regular changing of exhibited objects is to always give the visitor something new. But then the chance to go to the museum to see ‘my things’ or familiar themes disappears. For the visitor to this exhibition to take something home from it, it should better stimulate his or her interest with additional tools.

The story of Silesia as told in the Görlitz museum carries within itself a coded story of its origins. It is spread among memory, explanation and education. If memory is the legacy of the German expellees’ organizations, expressed asymmetrically in the individual stories and artifacts associated with their expulsion, then explanation is found in an attempt at rehabilitating the region. One can detect the didactic tradition of German museums in the purposeful periodization which however is rather unbalanced in the usage of the objects. Older eras are represented by ‘beautiful’ artifacts, the newer ones by much-used or everyday items. As an exhibition presenting a territory that mostly lies outside the borders of present-day Germany, it carries with it a strong consciousness of its geographic position, which is a significant difference from the other museums we are comparing. It must be added that its sober, didactic approach yields an impression of patronizing the visitor and is somewhat tiring by the end. However, the picture of Silesia it presents is more comprehensive and more layered than in Katowice and is more unified than in Opava.

The resonance and impression of a museum exposition is not based merely on its format and content, but also on the space syntax. From that perspective, the museums are mutually distinguishable, although they are similar in some respects.

Today’s museum in Opava is located in the town’s old museum building, constructed in the spirit of late historicism as a symbol of local Bildungsbürgertum. The building is therefore de facto an artifact in itself, and it is a dominant feature in a town that was heavily damaged by the War. As a result, it is somewhat bound by tradition, because the structure, constructed in the spirit of visual technology of the nineteenth century, dictates a certain arrangement, perception and reading of its exhibits. Fortunately, the curators who set up the exhibitions and displays are aware of that, and work creatively with their installations.

Also bound by the space it occupies, but in another way, is the museum in Görlitz, which is housed in a renovated renaissance palace joined to other buildings by a covered courtyard. Here, fragmentation and constraint prevent the development of a coherent flow. That would be no problem if entry to each room was encouraged by a different approach to its subject matter.

The museum in Katowice stands as an example of a newly built cultural complex with an ideal configuration. The museum building is generously conceived, and the historical exhibition takes up only part of the building, facilitating future changes. The fact that it arose more or less on virgin turf in a former industrial complex, with only symbolic institutional memory of long standing, creates a greater necessity for anchoring it in the awareness of the public. On the other hand, it is not restricted by maintaining tradition.

Considering its dependence on the surrounding cultural infrastructure, the non-existence of competing institutions, and the proximity of other towns in the area, the museum in Katowice clearly aspires to be a supra-regional player in the broader Polish cultural scene. The situation in Opava is the opposite. Opava’s Silesian Museum includes the National Memorial of the Second World War in Hrabyně and an exhibition in the birthplace of a local poet of national renown, Petr Bezruč. Nevertheless, the emphasis here is placed more on school field trips and family outings than on an attempt to introduce new historical themes and encourage public discussion. The museum in Görlitz is more a place for visiting one time on a vacation than it is for regularly wandering through the local culture.[9] However, the town is well-equipped with museums. Besides the Silesian Museum, it is home to three other outstanding cultural institutions. The Senckenberg Museum of Natural Sciences caters to its visitors who are children, a museum of Lusatian history is found in the Kaisertrutz fortress, and the Baroque House with its famous library that for all intents and purposes is a museum of the dawn of modern science.

The museums’ different contexts and approaches to the visitor are perhaps most apparent in their museum shops. While the store in Katowice is spacious and offers a wide assortment of professional and popular literature, as well as stylish souvenirs, the Görlitz store is a smaller shop with a limited offering. The situation in the Opava museum is somewhat startling in that it seems to have dispensed with any commercial activity at all and is satisfied with selling a few books written by museum employees at the ticket desk. From this seemingly banal matter one can see that for Katowice, Silesian identity is a living thing, while in Görlitz it is a relic of the past and in Opava, it is apparently antiquarian clutter.

After visiting all three Silesian museums, it seems that what influences how they reflect on Silesian identity, besides their differing interpretations of history, is their different cultural landscapes, that is, their diverging traditions and diverse application of current trends in museum presentations. It would be interesting to do a comparative survey among the visitors to these three flagships of Silesian identity and study the extent to which these museums fulfill their mission to revive it. Although each of the Silesian museums offers a different staging of the past, they all share surprisingly similar shortcomings. Besides lacking a multi-layered approach, they offer insufficient opportunities for self-reflection and lack participative elements, which are characteristics of the so-called New Museology. In their interpretations, they neglect many of the questions that the historiography of the last forty years has raised. The problems of the dead ends of history, of twisted ideas and pathological acts are missing, along with the general issue of the constructiveness of human interactions.

In the end, it appears that simple knowledge of the craft, a fat budget and the application of innovative media technology do not suffice, if they are not used by tight-knit teams drawn from various specializations. With their methods of staging exhibits, accompanied by obvious political pressures, the three institutions I have compared will remain, despite their many clearly positive attributes and, in the case of Katowice, clearly pan-regional ambitions only regional players without aspiration to face the challenges of the twenty-first century.

Translated by Robert Kiene

Ondřej Táborský: Creating Silesian Identity: A Comparative Review of Three Regional Museums. In: Cultures of History Forum (21.06.2018), DOI:10.25626/0085

Copyright (c) 2018 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors

Patrick Metzler · 21.12.2022

Localizing “Our Germans”: The New Permanent Exhibition in Ústí nad Labem

Read more

Veronika Pehe · 11.05.2022

‘The Nineties’ on TV: Remembering the Transformation Era in Czech Popular Culture

Read more

Jiří Smlsal · 25.01.2022

The Stench of Pigs and the Authority of Historians: Czech Debates About the Lety Concentration Camp

Read more

Karolína Bukovská · 25.11.2021

(Re)construction of Czech History: The National Museum and its New Permanent Exhibition on the Twent...

Read more

Veronika Pehe · 21.07.2021

Czech Prime Minister Implicated as Communist Secret Police Agent – Yet Nobody Cares

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).