25. Oct 2015 - DOI 10.25626/0118

Dr Daniel Logemann is Managing Director of the European Kolleg "Representing 20th Century" in Jena, which deals with European cultures of history, and aims to establish a program of study for museum workers who curate 20th century history. From 2010 to 2015, he was a member of the research staff and curator at the Museum of the Second World War in Gdansk. He has published on issues related to the Museum's forthcoming permanent exhibition, as well as on relations between citizens of the GDR and People's Poland. His 2012 monograph, “Das polnische Fenster: Deutsch-polnische Kontakte im staatssozialistischen Alltag Leipzigs 1972-1989” was the first book in the Imre Kertész Kolleg's series, published by Oldenbourg Verlag.

With twelve countries, 36 biographies and 500 objects, this exhibition seeks to give a tangible sense of Europe’s post-war history. But without posing questions to guide visitor’s engagement, or showing a willingness to draw comparisons, it fails to rise above mere eclecticism. The major themes of the war’s end are treated with political and historical correctness, yet tamely. The aim is to interweave people’s daily experience with the grand panorama. Overall, however, the German Historical Museum (Deutsches Historisches Museum; DHM) fails in its attempt to grasp European history as a zone of interconnections rather than parallel strands.

In its exhibition '1945 – Defeat. Liberation. New Beginning. Twelve European Countries after the Second World War', the DHM aims to tell of a new beginning following a terrible end. The title's focus on a sharply-defined watershed moment and on established historical and cultural catchwords is already part of the problem: The exhibition does not attempt to provide a systematic European overview, and its explanations and interpretations remain general and vague. As the curators Babette Quinkert and Maja Peers themselves admit in the exhibition catalogue, the "segments treating the different countries […] are consciously presented side by side, without attempting to relativise experiences and sufferings by balancing them against each other".[1] But without historical and critical contextualisation or historical comparisons, which, after all, need not necessarily lead to relativism, the title stands as an unproven assertion: a liberation and a new beginning that can neither be confirmed with arguments nor questioned by exhibition viewers.

It should also be noted at the outset that the choice of these twelve countries is untenable.[2] It is difficult to follow curator Maja Peers' claim that, alongside Germany's neighbors (leaving out Switzerland) and the victorious European powers of Great Britain and the Soviet Union, Norway was especially 'interesting'.[3] One can only speculate whether the DHM was guided in this selection by pragmatic reasons or other ones difficult to communicate; but without Italy or at least a southeast European country, it leaves a gap that is difficult to justify.

The exhibition is divided into spaces of irregular size using varying communication strategies. There is not just one but two introductory sections, followed by the twelve country sections, which are grouped into three spaces. A space with texts on the twelve countries is followed by a space with 36 biographies, which form a focus of the exhibition, and then a space with objects, the largest room. In between, as something of an afterthought, are multimedia screens with additional information on World War II as well as four hands-on installations focusing on overarching themes. In the largest space, the final one on the exhibition's thematic axis, the exhibition organizers draw on a wealth of historic objects. These circa 500 pieces from more than 150 lenders make it clear that the DHM has leveraged its international reputation and its organisational capacities to cultivate the core of traditional museum presentation. Departing from multimedia trends, objects are used to convey the narratives of the individual countries. However, although diverse thematic and graphic links join this section with the other space, the selection and combination of the objects and object texts does not permit general conclusions to be drawn about individual countries or about these countries as a whole. Narrative strands are left dangling, and assertions peter out into generalities. The end of the exhibition does not answer the question posed at the beginning. Like the exhibition space in the basement of the DHM, the narrative fans out, and visitors are unable to fold it back together.

At the same time, the fan shape has been skillfully used for the purposes of the exhibition. Visitors enter the exhibition through a dark room that presents an atmospheric prelude with quite ordinary means. Different countries’ radio broadcasts from the last days of the war form a permanent background; and in the middle of the room a (corresponding?) radio is displayed in a stele-like case. Blow-ups of people and scenes of the war's end are projected onto the walls, reflecting emotions such as grief, joy or fear and situations such as celebrations, the destruction of Nazi symbols and the damage caused by the war. One wall displays a map of Europe showing the demarcation of the post-war borders. Although it is valid for exhibitions to present maps in simplified and more easily legible form, the choice of territorial shifts reflected in the map is puzzling. Thus, for instance, the Saarland is marked, but its status as a semi-autonomous French protectorate is not explained. For another thing, the areas "annexed by the Soviet Union" are represented by a crosshatched swathe reaching from Finland and the former Baltic States down to Germany, Poland and Romania. As the pre-war borders are not marked and the time frames are not made clear, visitors are forced to draw on their hopefully pre-existing knowledge of the pre-war order. Thirdly, the (formerly German) regions of Poland are described as "promised to Poland". In this way completely different reasons for redrawing borders are jumbled together; the word 'annex' leads visitors to assume that at least the Soviet Union must have played an active role in the process. The momentous phenomenon at the heart of the post-war border demarcations – the complete reordering of East Central and Northeastern Europe to the benefit of the Soviet Union – is left obscure.

Upon exiting the room, visitors meet with a text outlining the exhibition's agenda: to examine the state in which these countries' societies and political systems were left by the Nazi regime, the war and occupation, and the upheavals that were brought by the post-war period. The complexity of the time and individual fates is illustrated by 36 exemplary biographies – a common tendency in modern museum narratives.

The next space, forming the point of the fan, has an all-white color scheme. The main text tersely summarizes the war's humanitarian catastrophe. The vast numbers of the dead, the refugees and the homeless are presented in varying sizes on the opposite wall, etching them in the visitor's visual memory. The centre of the space contains an unsystematic arrangement of wooden steles of different heights, each topped with a portrait photo of one of the 36 people who, over the course of the exhibition, will stand for the fate of the Europeans during and after the war. On the ceiling there is a web of neon lamps that probably goes largely unnoticed (on a DHM tour of the exhibition, the guide explained that the intersecting neon tubes could symbolize the intersections of European lives). In this way the catastrophe of the war is symbolically intertwined with individual experience. The arrangement suggests that the individual biographies need not be seen as a representative cross-section, even if the selection and the interrelationships do not seem to be entirely haphazard.

Moving on from this space, one enters the main exhibition space, a semicircle that also has an all-white color scheme. In this semicircle, doors lead to rooms representing the twelve countries, with an introductory text next to each door, each text encompassing three thematically distinct paragraphs. Here it becomes clear that the "defeat" of the title does not apply to most of the countries – this focus on Germany in the title is a departure from the other themes of the exhibition. As in the previous space, the texts on the individual countries focus on humanitarian catastrophes and, with a mixture of themes that sometimes seems arbitrary, on the political and economic reorientations that took place amidst the process of coping with the war’s legacy, a process often involving legal and interethnic aspects. That Germany is treated as one country among many thus becomes a fundamental problem; ultimately this decision on the part of the DHM has the effect of absolving the Germans from blame, as cause and effect are no longer distinguished. In a broadening fan, Europe is spread out from northwest to west and east, with Germany lying between Belgium and Austria. This makes it difficult to distinguish between occupiers and the occupied, Germany and its allies, and the Allied Powers, and to understand the post-war blocs into which the countries were divided. Instead of sorting the jumble of historical facts in order to provide orientation, the exhibition offers, as Florian Peters aptly puts it in his review, a "series of snapshots from the different nations' histories"[4].

Visitors can cross over at will from the introductory texts into the twelve country sections located beyond them, causing the tour to increasingly lose direction; within each sector, too, the boundaries marked on the floor can be crossed at any time. To give visitors a better understanding of the exhibition, it should have been necessary for them to begin their circuit of each country with the appropriate introductory text; due to the variable paths visitors can take, this does not happen in actual fact. The layout of the exhibition causes visitors to rapidly lose track of which characteristics of the post-war order in each given country are being presented for what reason. Not to mention that it prevents visitors from identifying relations, much less comparisons, between the perspectives on the different national histories. The failure to guide the visitor dissolves historical relationships and thus narrative logic as well.

The individual country sections are defined by contrasting color schemes in shades of green, blue and purple – free from any culturally-coded symbolism, they serve only to optically distinguish the countries from each other. They are consistent in structure: Each introductory country text in the previous room presents three characteristic themes that will be explored in the areas beyond, centering on the biographies and the historical objects. In the case of France, for instance, these three headings are 'Punishment and Commemoration', 'Getting on with Life' and 'Return to the Republic'. If one held up the introduction to France for comparison, one would find a short paragraph devoted to each of these three headings. Due to the physical separation, however, most visitors are unlikely to notice this thematic connection.

Instead, each of the three segments within each country section is prefaced by a biography that introduces the theme and is no doubt intended to facilitate the interpretation of the following thematic block. The biographies form the clearly visible backbone of the entire exhibition, as explicitly stated by the curators. In addition, the biographical interlinkage is underlined by the fact that the biographical steles from the second room are echoed here with other means. However, given their brevity the biographical texts are unable to illuminate the thematic sections whose weight they are supposed to carry; even as a pars pro toto, some of the biographies function only rudimentarily.

This is due in part to the lack of balance in the selection of the 36 biographies. It clearly does not represent a cross-section of the population: 23 of the life stories are those of men and only 13 of women. Other parameters, too, indicate that the biographies cannot be meant to reflect a proportional representation of European fates. Eight of the people presented belonged to the resistance against the Germans, seven were active as politicians in the post-war order, four were collaborators, two were high-ranking officers and three were soldiers. At least there are portraits of six children and of five Jews. Only six of the life stories are of ordinary people from the masses of the war's survivors, for instance a former forced laborer, the child of a German soldier and a Danish woman, and a resident of Leningrad. Most of them stand out from the millions of ordinary people for various reasons, either as persecuted opponents of the Germans, important collaborators, deserters or survivors of massacres such as Oradour-sur-Glane. With their prominent positions, such people as Pierre Laval (a government minister in Vichy France), Lord Louis Mountbatten (Supreme Allied Commander in the Pacific, among other things) and Andrei Zhdanov (a member of the Soviet Politburo who worked closely with Stalin) stand out vividly against the 'grey masses'. All the same, the combination of biographies, which include a preponderance of relatively prominent persons, does not contribute toward their subjects' recognisability as historical figures. On the other hand, their lack of recognisability does not help make the fate of anonymous Europeans any more visible.

In addition, the curators have not been consistent in their aim of selecting biographies in order to outline the affiliated theme and establish a route through the objects. None of the biographies are echoed by the objects that follow. The mere highlighting of the biographies before each thematic block and the indication in the first main text that these are supposed to be exemplary biographies is not enough to make up for this lack of connection. Thus one increasingly gains the impression that each thematic block has been capped with a halfway appropriate biography without any thought being paid to whether the brief texts and exhibits (which sometimes include interviews with contemporary witnesses or pictorial material) really offer a meaningful introduction to the theme that follows.

At least the biographies, highlighted in contrasting colors, provide a visible orientation; the objects and display cases in the thematic blocks fail to catch the eye. There are large-format artefacts such as the dolls' dishes that Maria and Beate Oestreicher brought back to their home in the Netherlands after their captivity in Westerbork and Bergen-Belsen, where their parents died. Or the clothing and gear of a Polish partisan who fought against Soviet dominance. One striking display is the doll which Regina Agata Budvytytė, then six years old, took with her when she was deported from her home in Kaunas to Western Siberia. The wedding dress of the Dane Alma Bechmann Strøh, made in 1946 out of parachute silk, also has great value as an idealistic symbol and as a museum piece. Another Danish artefact is the cabinet containing the central card file of 'traitors to the nation' – not an attractive object, but quite an eloquent one. These individual objects are well situated in their historical context by detailed texts, and give a certain amount of scope to the life stories of their owners, users, etc. However, the individual objects rarely communicate with one another in a meaningful fashion. Often visitors must summon broad historical knowledge in order to draw connections between the arrangement of the objects and historical causes and effects.

For instance, in the section on Poland, the caption 'Shifting Borders' introduces the biography of Stanisław Bober and the camera with which he documented his family's resettlement to Upper Silesia from their home in what is now Ukraine. This is followed by a varied selection of objects, each of which stands for a complex problem of a post-war Poland rebuilt on the basis of ethnic homogenisation – for instance the propaganda poster 'Land Awaits in the West', a shipping trunk belonging to the Pole Stanisław Fryze from L'viv (which after the war went to Soviet Ukraine), an icon of the Virgin of Ostra Brama from Vilnius (post-war Soviet Lithuania) or a notice about the resettlement of Germans. Some of the themes addressed seem redundant, while a well-informed visitor might miss a Belarussian inflection or more details on the situation of national minorities on Polish territory. Less knowledgeable visitors are likely to have difficulty meaningfully processing and connecting the wealth of information, despite the object texts.

Many of the headings over the thematic sections are vacuous[5], but at least more or less reflect the common-sense perspective of historiographic scholarship. For instance, the room captions for Denmark – 'Almost without a Struggle', 'Homecoming and Transit' and 'Accusations and Consequences' – permit general associations, but they are so vague that it would be difficult to say what might have distinguished Denmark from Luxemburg, where the headings are 'Returning Home', 'Twice Liberated' and 'Demanding Co-Determination'. In some of the country sections one is indeed given a sense of the major political and social consequences of World War II: For Poland the headings are 'Destruction and Trauma', 'Redrawing Borders' and 'The Struggle for Power'. While the headings for Great Britain, 'Search for the Homeland', 'Deprivation' and 'Victory and Loss', do convey some kind of concrete impression.

But in the case of countries that are more complex in historiographic terms, such as Germany as the perpetrator of the catastrophe, or the Soviet Union as its beneficiary and the new usurper of power in East Central Europe, one can see in what an anodyne manner and how indecisively scholarly insights have been integrated into the narrative of the exhibition. The heading 'Guilt and Repression' for Germany reflects now-canonical notions, while the heading 'Division and Reconstruction' obscures rather than illuminates the history of the occupation zones in the run-up to the founding of the two German states. The heading 'A Society Scattered' does seem justified by the exhibition's logic, given the reference to displaced persons, Holocaust survivors and the many separated families – thus, the introductory biography does not belong to a German, but to the Soviet POW and forced labourer Mikhail Levin. Here the focus is clearly on the people who were living (often unwillingly) on German soil at the end of the war, not on German society as the war's breeding ground. But in this way the title gives the impression that the Germans themselves were victimised – by whom? At the same time, it simplifies and trivialises. This dilemma could have been tackled better by addressing other themes, such as the battle to the last, or the Germans' behaviour toward their victims. But apparently the exhibition is not intended to engage with historical controversies. And so the section on German guilt focuses mainly on perpetrators from the apparatus of repression and on the Nuremberg Trials – the fact that all Germans were implicated in crimes, acquiescence and other moral failings is blocked out.

The headings for the Soviet Union are 'Triumph and the Consolidation of Power', 'Punishment and Mistrust' and 'Scorched Earth'. Nowhere else in the object section does the exhibition explore the German policy of occupation and annihilation as clearly as in the last heading. It is perhaps a tribute to the fact that the war of annihilation claimed so many (not only Russian) victims on the territory of the Soviet Union. However, among other things it was this tabula rasa that made it possible for Stalin to tighten the screws after the war. But can this be explored under 'Triumph and the Consolidation of Power' when that section features mainly Soviet propaganda? The imbalance becomes quite clear in 'Punishment and Mistrust', which should really have been called 'Revenge and Repression' as the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung put it caustically[6].

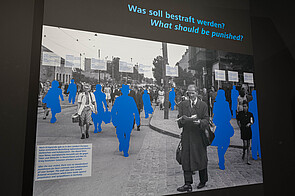

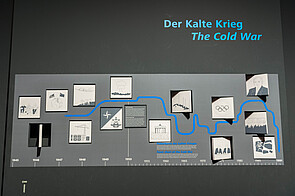

What impression ultimately remains beyond the simple juxtaposition of twelve European countries? Above the display cases, the space is dominated by political posters, newspaper articles and public appeals. In the showcases one sees, over and over again, boxes and suitcases and whatever people were left with after the war – the belongings they could cling to. One sees surrogates of the transition, sometimes a handmade piece of clothing, a prosthesis, a butterfly panel from a Berlin ruin. Almost everywhere the question of how to deal with war criminals and collaborators emerges. This question is dealt with especially audaciously in the Dutch board game 'Cowardly or Brave under Seyß-Inquart', where right or wrong behaviour earns players advancement or punishment. On the back, black wall of the exhibition, visitors encounter, more or less in passing, four installations with abstract, contrasting colors, which offer creative opportunities to absorb, process and question various themes of the exhibition. The titles 'What Should Be Punished?', 'Daily Life and Shortages', 'Forced Migration' and 'The Cold War' draw on the very elements that could be used to construct continuities in the biographies and showcases as well: policies toward war criminals and collaborators, the destruction and poverty of the post-war period, the shifts in borders and populations following Tehran, Yalta and Potsdam, the break-up of wartime alliances and the beginning of the Cold War. This section, shunted off to the back of the exhibition, is the only part of it that encourages visitor participation. Thus, on a didactically simplified level, it is actually able to deal with the core problems of the exhibition as a whole, while departing from the supposedly meaningful context of the different countries' characteristics. Ultimately visitors are hit over the head with things that had previously been hinted at, but not explicitly stated.

This curatorial decision is surprising, leading one to ask whether the exhibition could not have been constructed around concrete problems with questions and theses. This approach need not have dissolved the vividness of the national narratives, but would have given them a meaningful, interesting structure and opened up comparative perspectives on commonalities and differences. It would have forced the DHM to develop the exhibition on the basis of the problems of the time and to formulate theses. Then the title could no longer have been '1945. Defeat. Liberation. New Beginning'; to reflect the content, it might have been better put as '1945. Homeless. Impoverished. Estranged'. That would make contemporary visitors aware that in many parts of Europe the end of the war meant the end of armed conflict, but not the end of violence, inequalities and insecurity. The enormous civilising achievement of the post-war period was not inherent in that historic moment. But a visitor to the DHM in 2015 would not have this impression after viewing the parallel country sections. A Baltic partisan fighting the Soviet power, a Holocaust survivor living in fear of the majority population or desiring punishment for the perpetrators, a women publicly humiliated due to a relationship with an occupying soldier could not be so sure of a bright future.

Translated by Isabel Cole

Daniel Logemann: 1945 – Defeat. Liberation. New Beginning. Twelve European Countries after the Second World War. In: Cultures of History Forum (25.10.2015), DOI: 10.25626/0048.

Copyright (c) 2015 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

Webpage of the German Historical Museum (in English)

Hans Gutbrod · 30.05.2023

Sebald's Path in Wertach -- Commemorating the Commemorator

Read more

Matěj Spurný · 31.10.2021

The Colour of Compromise: The 'Documentation Centre for Displacement, Expulsion, Reconciliation' as ...

Read more

James Krapfl and Andrew Kloiber · 28.05.2020

The Revolution Continues: Memories of 1989 and the Defence of Democracy in Germany, the Czech Republ...

Read more

Sabine Volk · 11.03.2020

Commemoration at the Extremes: A Field Report from Dresden 2020

Read more

Gespräch · 30.11.2019

"In Auschwitz hat sich die Wirklichkeit entlarvt" - ein Gespräch mit Daniel Kehlmann

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).