22. Jul 2019 - DOI 10.25626/0101

Dr. Eva-Clarita Pettai is a research associate at the Imre Kertesz Kolleg, University of Jena . She has published widely on the politics of memory and transitional justice in the three Baltic states after 1991. Her current research focuses on legal frames of memory as well as on changing narratives and representations of 1989 in Central and Eastern Europe.

![The former KGB headquarters on Brīvības street in RigaAuthor: Edgars Košovojs [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)] Author: Edgars Košovojs [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]](/fileadmin/_processed_/e/8/csm_Stura_maja_b792d3839f.jpg)

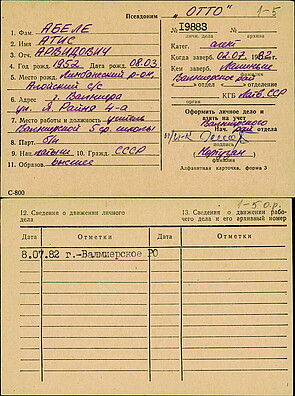

After two decades of political wrangling, failed legislation, expert interventions and often wild accusations, the Latvian parliament decided in fall 2018 to finally disclose, and even publish in parts, the contents of the notorious ‘Cheka bags’. With this term Latvians refer to around 4600 index cards of former agents and informers that were left behind in cloth postal bags when the Soviet secret police (KGB) left the country in 1991. Later, a partially destroyed electronic database (‘Delta Latvia’) was recovered containing records of conversations and summaries of agent reports compiled by KGB personnel. All of these materials were now to be transferred to the National Archive over the course of spring 2019. While the index cards were published as scanned copies on a special website of the National Archive in December 2018, access to ‘Delta’ remains restricted to academic researchers and journalists.

Previously, this sensitive material had been carefully guarded by the Centre for the Study of the Consequences of Totalitarianism (Totalitārisma seku dokumentēšanas centrs, TSDC), a unit within the Latvian State Security Agency (Satversmes Aizsardzības Birojs, SAB), responsible for preserving and researching the materials and for vetting electoral candidates. Due to this latter function, names of several high-profile politicians and officials, but also more rank-and-file public employees, had been revealed to the public over the years. Nevertheless, the fact that the KGB catalogue was not accessible to most Latvians – and that its guardians at the TSDC, as well as many politicians and experts, vehemently resisted efforts to disclose its contents – has been fodder for much speculation and conspiracy theories over the years: speculation about who could be in these files and theories about what a disclosure of agent names would mean for Latvian society and state security. Now that the full names of former agents and informers are revealed, new questions have emerged: about the value of the available information, about individual motivations and actions, and about what the new data can tell us about Latvia’s society under Soviet rule.

The aim of this article is to provide an overview of the public debates that accompanied the decision to disclose the contents of the archive. In order to provide background, I will briefly reconstruct Latvia’s post-1991 lustration legislation and policies, as well as the concomitant political controversies, which culminated in the 2014 principle decision to open the archive. In a next step, I will review the debates that followed this decision. These mostly revolved around the work of a government-appointed expert commission tasked with assessing the materials stored at the TSDC and making practical and legal recommendations for their disclosure, to be submitted by June 2018. Finally, I will give a first assessment of the ongoing debates in the media by focusing on two high-profile multimedia series on the matter (TV shows, podcasts and investigative reporting) that were launched in December 2018.

In contrast to a widespread opinion among Latvians that the country never engaged in lustration after 1991, the state actually implemented a number of procedures to prevent former KGB agents from holding public office. Among the three Baltic republic, in 1991 Latvia was the only one that found itself in possession of KGB material that involved politically rather sensitive information which was, however, left behind in a rather chaotic state. Therefore, the Supreme Council established a special commission in 1992 and tasked it with restoring and systematizing the data and documents, as well as laying the groundwork for a full-fledged institution that would preserve and research these materials – what would eventually become the TSDC. In 1996, this institution was subordinated under the auspices of the SAB, a move that would eventually have quite an impact on the debate over whether or not to release the information in the ‘Cheka bags’.

At first, no formal procedures were established to use the data for purposes of lustration. During the first parliamentary elections in the fall of 1993, candidates were simply required to submit an affidavit declaring that they did not and had never worked for either the Soviet-Latvian state security, the Soviet Défense Ministry or any other intelligence agency. Shortly after the successful elections to the first Latvian Saeima (parliament) after regaining independence, the commission announced that – despite the affidavit – the names of five elected representatives appeared in the KGB files. No further details were revealed about the identities of the MPs or their connection to the KGB. The legal and political wrangling that followed eventually led to the adoption of a new "Law on the Preservation and Use of Documents of the Former State Security Committee and the Determination of Individual’s Collaboration with the KGB” in 1994 that (in conjunction with the electoral law of 1995) stipulated the systematic vetting of electoral candidates prior to both national and local elections by the TSDC. Moreover, the TSDC was mandated to research and complement the materials where possible and to provide information upon request to state authorities and individuals inquiring on their own behalf. By 2018, around 3000 people had made use of the latter option. Finally, the law detailed the proceedings for individuals to appeal to the court to get their names cleared and regulated an individual’s dismissal from the electoral list and/or office in those cases where collaboration with the KGB was legally established. Between 1994 and 2018, 385 individuals turned to the courts to have their non-collaboration with the KGB legally confirmed, among them several elected representatives and holders of public office. 309 of these cases would eventually go to the courts; in only 15 (or 4.85 per cent) of these cases, the courts established the “fact of collaboration with the KGB” – in all other instances, collaboration could not be legally confirmed – in most cases the information gained from the documents left by the KGB was insufficient to establish wrongdoing in legal terms.

In 2004, when the originally set term for these procedures was to elapse, the 1994 law was amended to continue the measures. The government was now required to review the need for these regulations every five years. The 2004 amendment came amidst a legislative struggle in which the Saeima had tried to push through a regulation that would allow the full disclosure of all names contained in the ‘Cheka bags’, only to be repeatedly vetoed by then President Vaira Vīķe Freiberga. Her main argument, in which she agreed with other experts familiar with the contents of the archive, was that the information that could be gained from the catalogue of agent names and other material was often devoid of substantial information and too incomplete to serve the purpose of truth-finding; quite the opposite, that a blanket disclosure of these materials to the public would only cause disruption and divisions in society.[1] For the next ten years, the issue of whether or not to ‘open the bags’ lost its momentum, remaining on the agenda of only a few, mostly national-conservative MPs, activists and some historians. Moreover, the financial crisis of 2008/9 curbed the TSDC’s research into the material, as the Centre’s functions were reduced to archival work and routine vetting.

The relative silence on the matter, however, did not by any means imply that the issue had been settled. The fact that the ominous agent catalogue remained so carefully guarded by the SAB, inaccessible even to researchers and journalists, fed all kinds of (conspiracy) theories about whose names it might contain and why they were hidden from the public eye. In 2014, with another review of the 1994 law pending and another parliamentary election due in October, those who had always argued for “revealing the truth” saw a new opportunity to finally settle the issue. Again, experts warned of the potentially destructive effects of an unqualified release of names, pointing once again to the limited information available.[3] In the end, however, the advocates for disclosure prevailed. The passage of time clearly worked in their favour, as arguments about the dangerous political potential of disclosure seemed less convincing given that the documents dated back 30 to 40 years, if not more. Moreover, thanks to the existing vetting of electoral candidates and public appointees, no major political scandals were to be expected. The generational shift among MPs further limited that possibility, and arguments in favour of leaving the documents to the historians gained greater resonance. In the end, practical and legal concerns regarding the modalities of disclosing personal data nevertheless remained, and a compromise was struck. The newamendment to the 1994 law prescribed the full disclosure of the materials stored at the TSDC by late 2018, but only after a government-appointed independent expert commission scrutinized the materials and had the opportunity to make concrete recommendations as to their release to the Latvian public.

In August 2014, the Government Commission for KGB Research (Valsts drošības komitejas zinātniskās izpētes komisija) was established. Some twenty-six members, including scholars of history, the social sciences and law were loosely organized around a core group consisting of chairman and historian Kārlis Kangeris and his deputy, legal expert Kristīne Jarinovska. Due to unclear finances and institutional affiliation, the commission only commenced its research about a year later, in spring 2015. With a budget of over 700,000 Euro until 31 May 2018, commission members were able to pursue various research projects, solicit additional expertise on specific questions, organize national and international conferences and publish the results in various volumes. By late 2017, however, public criticism about slow progress and ineffective operations started to mount. It was revealed that the commission had yet to gain access to the most sensitive material, the card catalogue and database, stored at the TSDC – the evaluation of which had been its core mandate.

This is not the place to go any deeper into the arguments and angry accusations that defined the final months of the KGB Commission’s work.[3] From the start, there had been a clear mismatch between political and media concerns with the agent card catalogue and its possible revelations and the commission’s own interest in providing a thorough scholarly evaluation of the KGB’s structures and activities. It is open to discussion to what degree the leadership of the commission fundamentally misunderstood the foremost political and practical function of this body, or to what degree the commission’s work was deliberately undermined by those opposed to the disclosure of the catalogue. The SAB certainly played a rather obstructionist role in the whole process, repeatedly questioning the commission’s efficiency and refusing to grant unconditional access to the files to researchers. Moreover, SAB director Jānis Maizītis was one of those who repeatedly warned about the potentially destabilizing effects of a full disclosure for the country.[4] The KGB Commission replied by insinuating that the SAB’s reluctance to hand over the documents meant that the institution had something to hide.[5]

When the SAB finally granted unconditional access to the materials at the TSDC to eight commission researchers in early 2018, they had to work quickly to confirm the authenticity of each index card and to provide an overview of recruitment patterns and agents. Given the extremely narrow timeframe available, the analysis of the documents remained limited. Still, the commission managed to submit a final report with only a slight delay, which – for the first time and extremely pertinent for future researchers – detailed the contents of various archives, proposed new legislation, and called for the full disclosure of all KGB materials. The report reiterated the fact that the available materials were incomplete and insufficient to serve as evidence for establishing the nature of individual collaboration with the KGB. It nevertheless stressed that these documents are “part of the national heritage” and provided important historical insights into KGB recruitment strategies and operations, especially in its later years. The balk of the index cards dated from the 1980s and showed how the KGB recruited individuals from among all layers of society, but in particular from among the artistic community, academia and the churches.

This fact – the realization that many esteemed (and often still active) Latvian writers, composers, conductors, journalists, musicians, academics and church leaders had in one way or another cooperated and conspired with the Soviet state security apparatus – rocked Latvian society the most. It triggered a renewed confrontation, both in the media and in private circles, with questions of guilt, deception and betrayal – a conversation reminiscent of the early 1990s that has returned with a new vengeance and arguably a new quality.

After the National Archive published the scanned agent cards on its special website, many people registered to find out whether the names of former colleagues, neighbours, friends or family members appeared there. They soon realized for themselves what experts had talked about for years: that the names, code names, recruiting officer and time and place of recruitment (the only information on these cards), said little about the nature of a person’s cooperation with the KGB, why they had agreed to supply information and even whether they had in fact agreed and cooperated at all. In short: without further material and evidence, there was not much else to do than point fingers and make assumptions – or to ask those on the cards who were still around for the missing information. In what follows, I would like to concentrate on two multimedia series that did exactly that. The LTV series Pašlustrācija (self-lustration) provided a platform for individuals whose name were among the cards to come forward and tell their stories; the DELFI.lv series Maisi vaļā (bags open) featured expert interviews, investigative reporting and TV interviews with former agents and informers about their interactions with the KGB.

To be sure, name revelation and personal story-telling was not the only form of media engagement with the topic. Many of the headlines over the course of the past six months concerned, for example, legal questions involving the disclosure of personal data; others discussed the process and politics of the data transfer from the SAB to the National Archive or debated the degree to which a person’s post-Soviet achievements for Latvia’s culture would outbalance former trespasses. There were also op-eds and articles by historians (many of them members of the KGB commission) who discussed the historical value of the new sources and presented initial findings. Yet, a deeper historical inquiry on the basis of the newly available material is only just beginning, and thus far, there has not been any significant revision of previously held historical interpretations. Indeed, the public debate is less concerned with history than with the issues of transitional justice – namely what the delayed engagement in truth-seeking and dialogue means for Latvian democracy, for the “moral purification of society” or matters of justice, as reflected in the two media series.

The LTV series Pašlustrācija grew out of narrative interviews with Latvian intellectuals, artists and academics initiated by screenwriter and film-maker Gints Grūbe and investigative journalist Sanita Jemberga for the documentary Lustrum. First screened in November 2018, the documentary addressed “the entanglement of many cultural figures and atmoda [independence] activists with the KGB in the 1980s.” Skilfully combining original footage from the 1980s and early 1990s with contemporary material and interviews, Grūbe and Jemberga composed a film that featured a number of well-known figures from Latvian political and cultural life. Some of them had previously been exposed as informants, others only ‘came out’ about their encounters with the KGB in the film and talked about their moral dilemmas; still others spoke more generally about a time of constant awareness about possible infiltration or about being the target of KGB operations. The film-makers were also somewhat successful in reaching out to former KGB recruiters to hear their side of the story. As they state in interviews, their aim was not to “de-mask” or judge those who admitted to colluding with the KGB, but rather to hear these people out and show the often ambiguous and painful individual attempts to make moral choices in a deeply immoral system. Funded by the ‘Latvia100 cultural fond’, this documentary was something new in the Latvian context, not only in its investigative strength and socio-political message, as one critic pointed out, but also in its focus on the perpetrators rather than the victims of repressive measures. Some criticized the film for handling former wrongdoers with kid gloves and for showing too much sympathy with those who betrayed their neighbours and colleagues by informing on them – and for not sufficiently considering the victims.[6]

Indeed, the distinction between a wrongdoer and a victim of a state surveillance system that played with people’s careers and ambitions or used coercive methods to achieve compliance, is not always clear. The danger of collapsing important distinctions becomes even greater when personal recollections are the only source of truth, because available documentation is incomplete or non-existent, like in the Latvian case. Some Latvian intellectuals have warned about the consequences of such moral ambiguity in dealing with those “who put their own well-being first” for future generations.[7] Grūbe defended his approach, however, by pointing to “a gap” in Latvian academic and public discourse with regard to the stories of those who voluntarily worked for the previous system or otherwise complied. According to him, these people “are part of our state’s history” and their stories provide an important opportunity for later generations to understand “what exactly happened and what the starting points were from which the renewal of the Latvian state emerged.”[8]

The LTV platform Pašlustrācija now continues this approach of individual story-telling. In front of a camera, but without an interviewer, individuals discuss whether they knew they were being recruited (which some of them deny); how the recruitment happened or might have happened; what they actually did or did not do for the KGB; why they did not come forward by themselves even though many of them knew or suspected that their names were in the catalogue; what their past actions mean, back then and today. Highly educated as they are, the interviewees often move far beyond their own particular cases to explain life during late socialism, the way the KGB worked and the broader moral questions of having in one way or another supported the Soviet surveillance state. There is no dialogue, no probing, no historical background information, no further contextualization beyond the individual statements. It will be the task of future researchers to investigate how this series of self-lustration stories were received by the Latvian public. Considering the rather infrequent airing of these documentations, it seems evident that those who come forward to expose themselves in this way remain a minority.

The initiators of the series Maisi vaļā took a different, more confrontational approach. A team of investigative journalists around the award winning journalist Jānis Domburs working for the news agency Delfi.lv, descended on the National Archive to rake through the available agent reports and conversation records in the Delta database – and match the code names and personal case numbers with the information from the index cards in order to find out the real names of informers. Despite the partially blacked-out information in the database, they were able to identify a few dozen individuals who had repeatedly shared information with the security police, the most interesting of whom Domburs invited to appear on his show on DELFI TV or for an audio-recorded interview to confront them with the information uncovered.

Confrontational as these interviews appear, the investigations that accompanied them do not actually seem sensationalist or judgmental, but rather driven by historical curiosity about how interactions with the KGB evolved and what consequences they had. At times, it still became rather ugly, when interviewees defended themselves by accusing others of spying for the KGB or when those contacted by the journalists accused the media of character assassination. Others, however, appear rueful and cognizant of their own past wrong-doing, even while they ask for understanding and usually deny having caused any harm. Interesting were also certain reactions to the series’ publications from contemporaries that occasionally lead to further inquiries into individual cases and sometimes to interesting indirect – moderated and edited – conversations between former informants and their targets. In this, the series borders on a form of public truth-telling and dialogue that is vaguely reminiscent of some truth commission processes.

The sober nature and knowledge-driven, rather that sensational or accusatory, approach taken by Domburs and his team is further strengthened by a series of expert interviews under the same series title, conducted by journalist Māris Zanders. He interviewed mostly historians with experience with such archival material, who provided further insights into what these sources can and cannot say. Each interview focused on a different aspect of the KGB’s operations (for example, among émigré Latvians, academics or the church leadership), its recruitment strategies or anti-opposition measures. In its broader historical approach, the interviews were clearly meant to contextualize the individual stories from Domburs’ interviews and investigative reports. In its multimedia format and presentation of multiple perspectives, Maisi vaļā is clearly special and could potentially serve an educational purpose – with a wide-ranging impact on the long-term public perception of Latvia’s recent history and on those who were part of it.

One interesting observation regarding the media coverage of the KGB files discussed here is that both the Pašlustrācija and the Maisi vaļā series were spearheaded by journalists (and screenwriters) who themselves belong to a cohort (born in the early 1970s) that still has a clear sense of what it meant to live in Latvia during the 1980s. They might have been too young to be compromised by the regime, but they were old enough to follow, as budding journalists, the turbulent times of the 1990s quite closely, as well as the debates that followed, as the first prominent political and public figures were outed as former KGB agents and informants. Likely their own experiences explain their current interest in the topic.[9] Given that members of this cohort are now important members of the national media and have taken up quite a prominent role in the current public debate does speak against those who depict this as a conflict between those who lived under Soviet socialism and those who never experienced the regime themselves and thus “do not understand”, as was often suggested during last year’s debates. To be sure, there has been enough sensationalist reporting about the contents of the Cheka bags. Suddenly finding their names exposed in the media, more than one person felt a déja vue, having to battle unsubstantiated accusations and presumptions. The two series that were highlighted here, however, clearly pursue a different and more thoughtful approach and represent an ultimately healthy societal conversation about the ghosts of the past, about the character of the previous regime and about human weakness – but also moral resilience.

In May 2020, Latvia will celebrate its declaration of independence on 4 May 1990. The country is able to look back on three decades of largely successful democratic development, a thriving and pluralistic public sphere and a new generation of scholars and intellectuals interested in (and at times struggling with) keeping the country on a liberal-democratic track.[10] Learning about the past and facing up to some of its more painful questions is essential for this process to continue. For the past two decades, this mainly revolved around politicians and scholars addressing the more distant Stalinist and Nazi-era mass crimes and state terror. Public and scholarly debate focused primarily on the victims of these two totalitarian regimes, while the perpetrators were considered to have been, in the majority, individuals from outside the country.[11] The emerging public and academic discussion about the KGB’s activities within Latvian society during the later years of Soviet rule is different. Not only does it finally address the more recent Soviet period, it also predominantly focuses on perpetrators – on the Communist Party officials, KGB employees and those who, voluntarily or not, let themselves be recruited as agents and informers or otherwise work with the state security agency. Finally, there seems to be a genuine readiness in large parts of the media (and the wider public) to accept that black-and-white categories are not useful when dealing with the legacy of the late Soviet state; that it might be, however, worthwhile to navigate the difficult moral boundaries and to continue probing existing myths and assumptions. The debate has thus far not been very polarizing, and in the end, those who suggested all along that opening the ‘Cheka bags’ would benefit society more than harm it might be proven right.

See the special digitalized 'Archive of KGB Documents' put up by the Latvian National Archive (all in Latvian).

See for more background on the opening of the 'Cheka bags' the New York Review of Books article by Linda Kinstler (5 March 2019).

Mārtiņš Kaprāns · 29.11.2022

Toppling Monuments: How Russia's War against Ukraine has Changed Latvia’s Memory Politics

Read more

Katja Wezel · 17.08.2022

Feeling the Horrors of Latvia’s 20th Century: The New Exhibition of the Occupation Museum in Riga

Read more

Paula Oppermann · 31.05.2018

A Dual Legacy: Reviewing the New Exhibition at the Former Nazi Camp Salaspils

Read more

Pauls Raudseps · 12.09.2017

Unstable Stalemate: Latvian Liberalism in Limbo

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).