17. Aug 2022 - DOI 10.25626/0140

Dr. Katja Wezel is currently a Feodor-Lynen Fellow of the Humboldt-Foundation at the University of Latvia in Riga. Previously, she held positions as Research Associate at the Universities of Göttingen and Heidelberg, and as the DAAD Visiting Assistant Professor at the University of Pittsburgh. She obtained her PhD in 2016 at the University of Heidelberg for her dissertation on Memory Politics in Latvia, published as Geschichte als Politikum. Lettland und die Aufarbeitung nach der Diktatur (Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag 2016).

The Museum of the Occupation of Latvia in Riga is arguably the central museum of Latvia’s twentieth century history. Although it is a private museum, largely supported by donations from émigré Latvians, it is often part of the official protocol during foreign dignitaries’ state visits. It is thus fair to argue that the museum represents the dominant, state-sponsored narrative of how the 20th century has shaped Latvia. The name “Occupation Museum” is rather programmatic in this context as it stresses the fact that Latvia has been occupied by two foreign powers — the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany — between 1940 and 1991. During the Soviet era, the term ‘occupation’ was used only to refer to the Nazi occupation. To this day, the Russian Federation rejects the term ‘occupation’ for the period of Soviet rule in Latvia, which is why using this term in the museum’s name is an important part of Latvia’s memory politics – namely to assert their own narrative that accentuates the effects and consequences of Nazi rule and Soviet rule as having been very similar for the people of Latvia. Latvia has been on a mission to promote this narrative for the last three decades. Aside from the narrative of Soviet liberation and the victory over Nazism that Putin has excessively tried to promote since the mid-2000s, for Latvians (and other Balts), 1945 simply represents a continuation of occupation rather than a watershed moment in their history.[1]

The Occupation Museum’s new exhibition represents a complete revision and expansion of the former exhibition from the 1990s. Opened to the public on 1 June 2022 in its newly expanded and completely renovated building, the exhibition now has a new layout, new texts and a new design. At the same time, many of the older themes, including the focus on Latvia’s double (or triple) occupation and the suffering of the people of Latvia under foreign rule are still at the centre of the exhibition. What is new is a more detailed focus on the experience of Latvian exile and diaspora after the Second World War. Moreover, two new chapters were added to the exhibition that show how Latvians have fought for the regaining of their independence in the late 1980s and how they re-established a democratic state after 1991.

The Occupation Museum was founded in 1993 on the initiative of Latvian-American historian, Paulis Lazda. Additionally, a number of other Latvian Americans helped collect the majority of the money needed for opening the first exhibition. They established the Occupation Museum Fund (OMF) which first leased the rooms of the former Museum of the Latvian Red Riflemen: Latvia’s Red Riflemen had supported the Bolsheviks during the October Revolution and the Russian Civil War. As a result, on the occasion of Lenin’s hundredth birthday in 1970, the Red Riflemen were honoured with a museum located at a central square in Old Town Riga. After Latvia regained its independence in 1991, the Soviet museum for the Red Riflemen was closed down. What is left today is the name of the square that is also the museum’s address: Latvian Riflemen Square 1 (Laviešu strēlnieku laukums 1). Notably, the square is now dedicated to all Latvian riflemen who fought in the First World War, and not just those who fought in the Red Army. The Soviet monument to the riflemen still stands on the square next to the museum.

The original exhibition opened in 1993 and was devoted to the first year of Soviet rule (1940–1941) and the mass deportations of 14 June 1941. In 1994, the exhibition was expanded to also cover the period of Nazi occupation (1941–1945); the following year, the second Soviet occupation period (1945–1991) was added.[2] In 1997, the OMF was able to secure partial state funding. To this day, the Occupation Museum receives about 40 per cent of its funding from the State of Latvia, whereas 60 per cent still comes from the sponsorship of Latvian exile organizations through the OMF. Additional revenue comes from entrance fees that have been introduced with the new exhibition. Visitors to the new exhibition now pay an entrance fee of EUR 5 for adults and EUR 3 for students.

Despite talks of dismantling the old Soviet building of the former Riflemen’s museum, which many considered ugly, the Latvian state and the OMF decided to keep it, both as a monument and as a reminder of the dark Soviet era. Latvian-American architect Gunnars Birkerts’ concept for the museum was to keep the original building’s structure, whose bronze colour has faded over the years into a greenish black, and to simply extend it. His design concept argued that this would fit the museum’s message, contrasting the dark periods of the Second World War and the Soviet era with a new, brighter present and future of independent and democratic Latvia exemplified by a new white annex. The juxtaposition between dark and light is one of the key themes of the architect’s design and is mirrored in the museum’s motto displayed at the exhibition’s entrance: “Through the labyrinth of darkness leads a thread of light.”

After ten years of using the former American embassy in Riga as an interim exhibition space while the Museum’s building was under construction, the Occupation Museum has now returned to its permanent (and previous) location at Strēlnieku laukums. Standing directly next to the Occupation Museum is one of Riga’s most significant sites: the restored House of the Blackheads, important for the city’s medieval and early-modern Hanseatic History and a real tourist magnet. The Occupation Museum clearly benefits from its location in this neighbourhood: in July 2022, the new exhibition drew 11,000 visitors, which is almost as much as the previous exhibition drew before it was moved to the American embassy in 2012 and this is quite promising considering the reduced number of tourists this year due to the war in Ukraine.

When entering the new museum, the visitor finds a large white room with a reception desk and an inviting hallway that contains a small exhibit on the history of the building. The visitor then takes the stairs to the second floor where the actual exhibition starts in another large white room devoted to the history of interwar independent Latvia (1918–1940) — the period in which Latvia was an independent and democratic state for the first time in its history. The nature of this independent state is represented by its constitution, whose first six articles are projected onto the central wall, one after another in a continuous loop. The main design element of the room, however, is represented in numerous photographs of Latvia’s society during the interwar period: these black-and-white pictures show families from various regions, individuals of different professions, including people representing Latvia’s various ethnic minorities. The Russian minority, for instance, is represented by a photograph of a class of students from a Russian school; there is also a photograph of Paul Minz (Pauls Mincs), Jewish-Latvian co-author of the constitution of Latvia, who was deported by the Soviet authorities in 1941 and who died in a Gulag camp; the German minority is represented by a picture of the politician and long-term editor of the Rigasche Rundschau, Paul Schiemann.

The text explaining Latvia’s history during this time period is brief, the main focus is clearly on its visual component. Overall, the museum’s texts do not overwhelm the visitor; rather, they provide the most important information — in both Latvian and English — but they clearly draw the visitor’s attention to the visual exhibits. What is noteworthy about the photographs, especially the family portraits, is that several of them re-appear throughout the exhibition. The visitor will learn about the fate of these people as a result of the occupations in the rooms that follow. This personalized view of history is a new feature of this exhibition. It clearly resonates with current standards of museology around the world, which aims to place more emphasis on individual experience. However, the museum could provide more explanation of this feature – the author herself only realized the recurring family photographs when visiting the museum for the second time.

The second room, to which one arrives via another small set of stairs, is devoted to the Hitler-Stalin Pact. The visitor is made to pause at this point as a short film (without sound) briefly explains the history of the Hitler-Stalin-Pact through a set of maps and photographs. The film also embeds the 1939 “Mutual Non-Aggression Treaty”, as it was called then, into a global context and the history of both Nazi and Soviet rule. The message of this short film is clear: in 1939, Hitler and Stalin divided Eastern Europe among themselves, and while both dictators were following a different ideology, the outcome was similar: the Holocaust on the Nazi side, the Holodomor on the Soviet side; Jews and other non-Aryan people as enemies of the former, wealthy people as enemies the latter; Kristallnacht and extermination camps under Nazi rule, the Great Terror and the Gulag prison camp system under Soviet rule.

The following exhibition space on the second floor is structured both chronologically and thematically and is divided into seven sub-sections or successive chapters: 1) the first Soviet occupation, 1940–1941; 2) the mass deportations of 1941 and 1949; 3) Nazi occupation and the Holocaust, 1941–1945, 4) the post-war period and the resistance movement; 5) the Gulag and the life of deportees in special settlement areas; 6) the “Sovietization, Russification and Colonization of Latvia”, 1944–1988; and 7) the exile of Latvians in the West, 1944–1991.

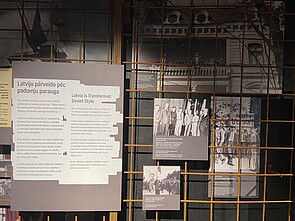

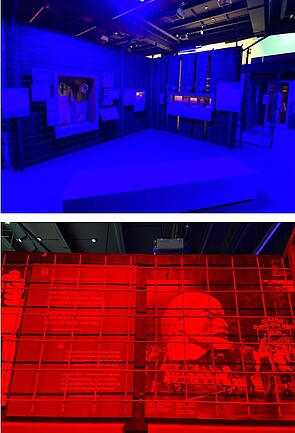

The exhibition contrasts elements of light and dark as well as various colours as a structuring device. One of the key design elements is making the exhibition appear like a labyrinth that the visitor could almost get lost in. Another feature is the use of a metal grid on the walls whenever the exhibition refers to the politics of the occupation powers. Meanwhile, the resistance movement, for instance, is portrayed on white walls. Each main part of the exhibition has a different dominating colour: while the dominate colour to represent the Second World War, including the first year of Soviet rule and the Nazi occupation, appears in grey, the post-war resistance movement is mostly represented in white. At the beginning of the section that tells the story of the armed anti-Soviet resistance in Latvia’s forests – the “national partisans” – there is a large photograph of green trees. The peaceful image, however, is contrasted with dangling laces from the ceiling that intensify the labyrinth-like character and symbolize the fact that this resistance movement was crushed soon after the war.

The section of the exhibition that deals with the mass deportations of 1941 and 1949 is immersed in a dark blue neon light — the blue is supposed to symbolize the coldness of Siberia, where most of the Gulag camps and special settlement areas were located. One has a strong urge to quickly leave this room, which is unfortunate since the curators have compiled many interesting exhibits and personal stories of how people survived the Gulag despite hunger, cold, sickness and the death of loved ones under dire circumstances. The feeling of claustrophobia is mirrored in the following section that deals with Soviet rule in Latvia. This time, neon light bathes the entire room in red. One of the main problems with this artistic choice is that such feelings of claustrophobia are superimposed on the visitor at the cost of information. Trying to read all the information provided while enduring the neon light becomes a tiring task. The use of these coloured neon light is, indeed, currently being debated amongst the tour guides and the museum leadership. According to the head of the exposition department, Aija Ventaskraste, the museum management is collecting the reactions and opinions of its visitors and may eventually decide to tone down the neon lights in order to allow for a better reading experience.[3]

Noteworthy is that throughout the exhibit that deals with the Second World War, both Soviet and Nazi rule are presented completely en par and indeed intertwined with one another, which serves to mirror the Latvian experience. Before the sections on Soviet deportations and the Nazi takeover — the first Soviet mass deportation occurred a mere week before the German Wehrmacht entered Latvia in late June 1941 — there is an installation with two cattle wagons. These wagons symbolize the fate of the deportees, who were brought to the Gulag camps and to special settlements in remote areas of the Soviet Union during the two mass deportations in 1941 and 1949. The arrangement of the cattle wagons, the lack of any strict separation between the rooms and the fact that there is no specific explanation given on the cattle wagons, allow the visitor to also see them as symbols of the Nazi occupation and the Holocaust. For Latvians, cattle wagons largely remain a symbol of the Soviet mass deportations since the majority of Latvia’s Jews were shot on-site and not taken to extermination camps by train; however, the wagons can also be understood as a symbol for the Holocaust. Nazi authorities transferred approximately 20 000 German and Austrian Jews to be incarcerated in ghettos, camps or shot at killing sites in Latvia. While their fate is only briefly mentioned in the section on the Holocaust, the artistic way of using the cattle wagon allows the visitor to make the connection and have one’s own thoughts on the subject.

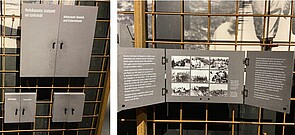

The exhibition shows how the two dictatorships not only replaced each other, but how there were overlaps between them that clearly affected the Latvian people at the time: for instance, the murder of central prison inmates by the Soviets which took place just prior to the Nazi takeover of Riga and was immediately followed by the Nazis’ propagandistic display of the dead bodies, all of which was combined with propaganda campaigns against “Jewish Bolsheviks”. One of the curators’ artistic choices will likely attract criticism by members of the Jewish community both within Latvia and abroad: the panels depicting the Holocaust use the device of shuttered windows that contain the information about the killing of Latvia’s Jews. The window shutters have to be actively opened by the visitor if they want to learn about the killings and those responsible for them. According to Aija Ventaskraste, such a method is employed as a way of respecting the privacy of the victims.[4] One of the most brutal visuals of the Holocaust in Latvia is the mass killing of Jews in the Dunes of Liepaja in 1941. Stripped of their clothes, the victims were forced to stand in front of the shooting pit. Since the new exhibition particularly welcomes school children and has included special exhibits for the younger ones, the curators wanted to hide such brutal photographs so that the visitors can decide for themselves whether they want to be exposed to them.

Altogether, the extermination of Latvia’s Jews – around 70 000 people – is covered relatively briefly in this exhibition. While there is an entire room devoted to the special Soviet police – usually referred to by Latvians as “Cheka” – and the Soviet terror system, the Holocaust is mainly covered on one wall of the room that deals with the Nazi occupation-period, and it hardly highlight personal stories of the Jewish victims. There is more focus on the perpetrators — both Germans and their Latvian collaborators — and on the Latvians who saved Jews. The museum features one Jewish survivor, whose story is portrayed in a video, although sadly without a listening device. Instead, one has to read the subtitles. This is a general problem throughout the museum: there are no headphones provided, a relic of the Covid-19 pandemic that might change in the long run. However, the curators could have easily included more photographs of Jewish families from Latvia in the first room and explained how the Holocaust altered their lives. Instead, the Jewish Latvians who are highlighted with individual pictures in the exhibition are those who fell victim to the Soviet deportations of 1941. One reason given for this choice is that there are other museums that focus primarily on the Holocaust in Latvia, for instance, the Museum “Jews of Latvia and the Riga Ghetto Museum.

New research is reflected in the exhibition, for instance, the fact that the end of the Second World War was also a war of brother against brother in the Baltics.[5] Both sides, the Soviets and the Nazis, conscripted Latvians into their armies, and indeed the curators found pictures of one of such Latvian families that exemplify this: one brother fought in the so called “Latvian Voluntary Waffen-SS Legion” while the other one was drafted into the Red Army.

There are altogether only three larger objects in the exhibition which is otherwise dominated by texts, visuals, video- and audio-installations. The first large object is an authentic door from the former prison in Riga-Brasa, a site that the KGB used to intern and interrogate political prisoners. This prison door is integrated into the room that portrays the human rights violations committed by the Soviet secret police. Next, there are the two previously mentioned wooden cattle cars which are accompanied by visuals that symbolize people being transported to the east. Finally, there is a wooden watchtower in the room that is devoted to the Gulag system and the special settlement of deportees in remote areas of the Soviet Union. It is modelled on a Gulag watchtower, albeit smaller, and it regularly illuminates the otherwise relatively dark blue exhibition room. From these three objects one can conclude that the focus of the new exhibition — just like in the old exhibition, which was centred around a reconstructed Gulag barrack — is on the fate of those citizens of Latvia who were imprisoned by Soviet forces, deported to Siberia, coerced to work in Gulag camps or forced to live in special settlement areas.

The next part of the exhibition on the "Sovietization, Russification and Colonization” of Latvia introduces life in Soviet Latvia through the lens of those who survived the Gulag or special settlements in the Far East and later returned to Latvia after the death of Stalin in the late 1950s or during the 1960s. As the exhibition explains, they returned to a very different Latvia, which had been Sovietized, whose economy was now centrally planned by Moscow’s authorities, and where thousands of Russian-speaking military personnel and workers had joined the workforce. The room draws attention to a number of items that were produced in Soviet Latvia, such as the VEF radio – a consumer item that those who lived in the Latvian SSR are often proud of to this day. At the same time, the exhibition texts indicate that during the Soviet era the Latvian SSR economy added more to the Soviet state budget than it received in monetary terms in order to build new infrastructure, industries etc. The exhibition calls this the effects of “colonization”. While the term was prominent in the exile literature on Soviet rule in the Baltics, it has been critically assessed by post-Soviet researchers[6] and is now hardly used by historians of the Baltic states. Use of the term in the exhibition is therefore also a sign of the continued influence of the Latvian émigré community in the representation of history at the Occupation Museum.

The last room on the second level is devoted to the experiences of Latvians in exile (trimdas latvieši), first in the post-war German DP camps, and later in the countries all around the world to which they emigrated, particularly Sweden, the United States, Canada and Australia. Part of the room’s exhibits also stress the exile community’s continued fight to keep the idea of a free Latvia alive. A large-scale video projection shows various demonstrations in the West, in which Latvians in exile fought together with their Estonian and Lithuanian counterparts to “free the Baltics” from Soviet rule. Apart from the initial video about the Hitler-Stalin Pact, this is the only part of the exhibition that includes references to the very similar situation of Estonians and Lithuanians. Otherwise, the exhibition focuses exclusively on the Latvian experience. The fact that the new exhibition dedicates a whole room to the Latvian exile community’s fate and activities during the Cold War, while this was rather absent in the previous exhibition, again reflects newer research that shows the significance of Latvian and other Baltic émigrés’ efforts to keep the Western publics aware of their countries’ fates.[7]

From here on the visitor will leave the labyrinth of darkness and take another staircase upwards to a balcony. Along the staircase the key dates of the Latvian movement for the renewal of independence are shown, starting with the first larger demonstration on 14 June 1987 in commemoration of the deportations of 1941 all the way to the regaining of state independence in August 1991. It is interesting that the human rights activists of ‘Helsinki 86’, who already began appeals for a renewed independence a year earlier, are only mentioned later in the exhibition. Once again, we can see here the curators’ focus on the suffering of Latvians and the role of memory for the independence movement. The exhibition on the balcony provides the visitor with information about crucial moments and actions that led to the restoration of Latvia’s independence in 1990, the recognition of its independence in 1991 and the country’s “return to Europe” by joining the European Union and NATO in 2004.

The exhibition ends as it started in the first room: with an emphasis on the Latvian constitution in its renewed form and its newly adopted preamble that states that Latvia is the state of Latvians and Livs (an ancient tribe which used to live on Latvia’s territory but who have by now almost completely been assimilated into the Latvian language and culture). This ending for the exhibition clearly falls short of realizing the promise made by the first room about Latvia’s interwar republic, which included an emphasis on Latvia’s minorities as an integral part of the country. The exhibition on the balcony juxtaposes Latvians with Russian-speaking Soviet settlers that immigrated to Latvia during the Soviet era. According to one text in the exhibition, “the occupation-period migrants are offered naturalization, but many reject it.” This is a reference to the citizenship laws of the mid-1990s that stipulated a naturalization process for all those who settled on the territory of Latvia after 1940. However, the text does not explain that these laws initially prescribed clear quotas, forcing many Soviet-era settlers to wait, often not gaining citizenship immediately, even if they wanted to. The exhibition also fails to mention the descendants of Latvia’s historical Russian, Polish and Belarusian minorities, whose families have lived in the territory of Latvia for 200 to 300 years and whose Latvian citizenship was renewed like those of ethnic Latvians in 1991. Yet, they are still not included in the 2014 constitutional preamble about what constitutes the Latvian nation. One can only hope that in the long run, the exhibition on the balcony will find a more inclusionary tone.

The new exhibition at the Occupation Museum of Latvia takes a decidedly Latvian point of view. This becomes obvious in the usage of terminology that is part of popular knowledge in Latvia but not so well known or used outside of Latvia. One example is the use of the term ‘Cheka’ and ‘Chekisti’ in reference to the Soviet secret police throughout the exhibition, also in the English translations. While one of the panels explains that this was the name of the Soviet secret police in the early years of the Bolshevik power in Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1922 — at a time when Latvia was not yet occupied by Soviet forces —, the exhibition asserts that in popular language this is the term used for the NKVD, later the KGB, throughout the occupation period and it is therefore used by the exhibition. The historically correct term at the time of Latvia’s first occupation, NKVD, which is also more commonly used outside of Latvia, is only briefly mentioned.

It is obvious from this exhibition that the museum wants to first and foremost do two things: a) commemorate the victims of the occupation powers in Latvia, with a strong focus on the longer Soviet occupation, and b) take a stand and bring to light the Latvian perspective on the history of the Second World War and its aftermath and make this part of the general European narrative. To borrow Ljiljana Radonic’s term, the new exhibition at the Occupation Museum in Riga is a “Memorial Museum” (Gedenkmuseum).[8] Judging the contents of the museum with this focus in mind, the new exhibition fulfils its given task.

Katja Wezel: Feeling the Horrors of Latvia’s 20th Century: The New Exhibition of the Occupation Museum in Riga, Cultures of History Forum (17.08.2022), DOI: 10.25626/0140.

Copyright (c) 2022 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editor.

Mārtiņš Kaprāns · 29.11.2022

Toppling Monuments: How Russia's War against Ukraine has Changed Latvia’s Memory Politics

Read more

Eva-Clarita Pettai · 22.07.2019

Delayed Truth: Latvia's Struggles with the Legacies of the KGB

Read more

Paula Oppermann · 31.05.2018

A Dual Legacy: Reviewing the New Exhibition at the Former Nazi Camp Salaspils

Read more

Pauls Raudseps · 12.09.2017

Unstable Stalemate: Latvian Liberalism in Limbo

Read more

· 01.01.1970

Latvia

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).