12. Apr 2015 - DOI 10.25626/0037

Sándor Horváth is a senior research fellow and the head of Department for Contemporary History at the Institute of History, Research Centre for the Humanities, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, and he is an editor of the Hungarian Historical Review (www.hunghist.org). His research interests include social and cultural history of the twentieth-century, everyday life, social identities, youth history, socialist cities, social policy and collaboration with the Communist regimes. His latest articles in peer-reviewed international journals were published in Journal of Social History and in Journal of East Central Europe. His list of publications includes four monographs with the forthcoming “Stalinism Reloaded: Everyday Stalincity in Hungary, 1950-1960” by Indiana University Press.

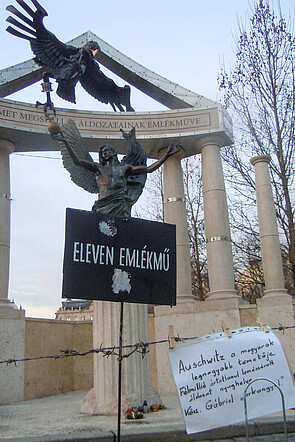

The Hungarian government declared 2014 the ‘Year of Holocaust Remembrance’ in response to accusations that it had failed to stem anti-Semitic tendencies in the country. In July 2014, however, a monument was erected on Liberty Square in downtown Budapest to commemorate the Nazi occupation of Hungary, which began in March 1944. The message of the monument is easy to read: Hungary was a victim of Nazi Germany. The earlier alliance between Hungary and Nazi Germany and the joint responsibility of Hungary for the deportation of over 400 000 Hungarian Jews is elided. Instead, the monument is dedicated to “all the victims” of Nazi occupation.

The Hungarian art historian Ernő Marosi, a full member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, shared his views on the plans to construct a monument to the victims of the German occupation of Hungary on Budapest's Szabadság tér (Liberty Square) in May 2014. In his talk he made the following remark: "There was never a Historikerstreit in Hungary. If there had been, we would not now have to discuss this banal and petty case with serious expressions on our faces. Rather we would be discussing it as it should be discussed, as one of a series of disgraceful vulgarities."[1] The audience, which included the most prominent Hungarian historians, were not always able to maintain serious expressions while listening to his highly entertaining presentation. Indeed there has not been such wide-ranging consensus on an issue among Hungarian historians for a long time. Historians who are often on different sides of the fence in other discussions and fights for position chuckled in concert in the course of Prof. Marosi's presentation, in which the distinguished art historian subjected the planned monument to an ironic analysis. They laughed perhaps the most heartily when Marosi made the accusation of plagiarism: the figure of the angel, which according to the design is being clutched at by the claws of the German eagle, can be found in the allegory on the 1834 escutcheon of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences; in the latter depiction, however, the angel represents not Gabriel, but rather Hebe, the beautiful woman of Roman mythology and the goddess of youth, raising a cup of nectar to Jupiter, who has taken the form of an eagle.

As became evident in the course of the symposium that was held on 13 May 2014 in the Department of Philosophical and Historical Sciences of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Hungarian academics, and in particular historians and art historians from the traditional academic institutions, were for once in clear agreement: the plans for the monument devised by the government were both banal and disgraceful. So where is the debate? And who are the debaters?

If indeed there is any debate on this issue, it is between professional and civic organizations on the one hand and the Hungarian government on the other. This is demonstrated perhaps most clearly in the fact that not a single major scholar, including conservative or right-wing ones, and not a single university or Academy historian whose position was secured by the present government, has publicly endorsed the monument. Indeed, the plans have been criticized by innumerable people who are close to or part of government circles, though the majority of the historians who are regarded as sympathetic to the government in general are unwilling to give an opinion on the matter, perhaps out of fear of losing their positions.

The official plans for the monument were not presented to the public by the government bodies that commissioned them or by the local government of Budapest's 5th District, which owns the land where the monument stands. The selection of the work itself and the decision to erect a monument on Szabadság tér in the first place were made entirely in secret. The plans only became known to the public when state secretary János Lázár, whose public nickname is 'Laser Joe'[2], acting on behalf of the government, asked representatives of the 5th District Local Government for their consent. By that time, according to the proposal, the public procurement procedure had already been completed, despite the fact that absolutely no information had been provided regarding tenders or alternate plans. Initially, only a short government decree was printed in Magyar Közlöny (Hungarian Bulletin), which publishes laws and decrees. According to this one – 565/2013 (31 December 2013) – the government declared the monument an issue of particular importance with regard to the national economy. In order to be granted permission to continue with the project, the government had to submit the plans for consideration by a meeting of representatives of the local government, which included representatives of the opposition parties as well. On 19 January 2014, in the middle of the election campaign, Tibor Pásztor, a representative of the Hungarian Socialist Party (an opposition party), uploaded all of the documents of the plans to his blog.[3] Two days later, the Government Information Center issued an announcement containing the following: "at the time the decree was announced, a labor and use contract not exceeding the limit for public expenditures was concluded [by the Office of the Prime Minister and] sculptor Péter Párkányi Raab for the preparation of a description of the technical specifications, concept, and plans for the work. This had to be completed by 3 January 2014. In other words, the sculptor had barely four days in which to come up with something."[4] Almost immediately, numerous organizations and private individuals, including several prominent historians, began to raise voices of protest.

According to the statement of protest authored by the historians who objected to the plans, "the monument is based on a falsification of history, it cannot serve its [alleged] function. By presenting the victims of the Holocaust and the collaborators as a single victim, it insults the memory of the victims."[5] Many university professors and members of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences signed the statement.

According to the documents that were made public, Péter Párkányi Raab and the Budapest Gallery, a non-profit art gallery of the Budapest Municipal Government, which has played a mysterious role in the whole affair, requested the professional opinions of two other sculptors, Miklós Melocco and György Benedek. Melocco is not unfamiliar to people in right-wing circles in Hungary. For instance, in 1999, during Viktor Orbán's first term as Prime Minister, he designed the sepulchral monument for József Antal, Hungary’s first prime minister following the fall of communism, in the cemetery on Kerepesi Avenue. Raab also designed government-commissioned statues for public spaces, and he also designed a monument to the Treaty of Trianon in 2010). According to an undated description of the Szabadság tér monument, the archangel Gabriel, who symbolizes occupied Hungary, has his eyes closed at the moment of attack: "We do not know whether he is sleeping, dreaming, or daydreaming. The composition indicates that the dream is turning into a nightmare." The orb, a national symbol dating back to the time of Saint Stephen, the first Christian king of Hungary, falls from the hand of the winged angel, who has only one wing and is therefore unable to fly. The eagle above the angel represents the Third Reich and according to the description is preventing Gabriel from flying. "Two cultures are portrayed: one, which regards itself as stronger (and is definitely more aggressive), towers high (it does this with the architectural context, a tympanum), then lands on and strikes a blow to the other, meeker, more delicate figure, the figure of the archangel Gabriel, who in the history of culture and religion is a man of God, God's strength, Divine strength, and who here represents and embodies Hungary." The Hungarian text contains misspellings and infelicities that make the description sound a bit more confused than it otherwise would.[6]

The monument and assessments of it have since become matters of public life. Some of the more impassioned responses to the plans adopt the parlance of historical remembrance, which is understandable, since the composition is more an instrument in the assertion of a monumental vision of the past than it is an attempt to further an understanding of the past. There is no real rational debate, which one could argue is hardly surprising given the irrational manner (dictated more by the politics of memory than anything else) in which the plans were created. The plans themselves were made public by a member of the opposition, not by the organs of government, which in principle ought to have sponsored a competition for the project, but did not. And while the entire project may seem irrational (the protests of civil and professional organizations notwithstanding), there is a rationale behind the creation of the monument from the perspective of the government. In order to understand this rationale, one must know a bit more about two acts in the monument drama that took place this year.

The scandal surrounding the monument can only be understood in the larger context of debates around the commemoration of 2014 as the sixtieth anniversary of the Holocaust in Hungary,[7] the revival of the Horthy cult, and the election campaign of spring 2014. On 10 February 2015 the Federation of Hungarian Jewish Communities (Magyarországi Zsidó Hitközségek Szövetsége, or MAZSIHISZ) sent a letter to the prime minister, Viktor Orbán, in which it specified, with regards to the Holocaust anniversary, that as a precondition of cooperation between the Federation and the government the prime minister would have to rethink the plans for the Szabadság tér monument.[8] A week later, in the midst of the election campaign, Orbán wrote a reply to MAZSIHISZ, in which he suggested that the Federation and the government continue discussions after the Easter holiday, since the election campaign hampered any sensible dialogue.[9] Many people took this as an indication that the government intended to postpone construction of the monument.[10] Originally the monument was meant to be unveiled on 19 March, the seventieth anniversary of the German occupation.

This is one reason why so many prominent opinion-makers in Hungary were outraged when, on 8 April, two days after the election, workers appeared on Szabadság tér in order to close off the part of the square that, according to the plans, would serve as the site of the monument. Orbán and his Fidesz party had won the elections handily, and their first important decision, as far as memory politics go, was to proceed with the monument’s construction. They claimed that Orbán had never once indicated that he would postpone it. Which, indeed, is true. He merely raised the possibility of a dialogue, which was never pursued. Up to this point, critics of the monument had first and foremost requested only this of the government: that it actually make good on the promise of continued dialogue; but the government failed to respond. Instead, it insisted that it was acting in accordance with the law and fulfilling its constitutional obligation by erecting a monument commemorating the loss of sovereignty in 1944.[11] In response, opposition parties and civil organizations staged acts of defiance by violating the cordons that were used to close off the site the very same day; and these acts were regularly repeated. Initially the police ignored them, but by May they no longer tolerated the protests. They formed a human wall of police officers surrounding the site, welded the cordons together, and had protesters forcefully removed.[12]

In the meantime, construction was proceeding, slowly but surely. By the time of the 'debates', only the two main figures (the eagle and the angel) and the tympanum bearing the eagle remained to be completed.[13] In a second phase following the elections, the protests took a new form. Szabadság tér became the stage for ongoing protests. In March 2014, an initiative entitled Eleven emlékmű – az én történelmem (The Living Monument – My History), which had begun on Facebook, took physical form on the square. Holocaust victims, survivors, and their family members and loved-ones began placing memorial stones and candles as well as other objects on the barriers surrounding the construction site, expressing their personal ties to the events of the Holocaust in Hungary. The objects included such things as "a piece of railway track wrapped in ribbon with the colors of the Hungarian flag, family pictures, children’s drawings, rolls of film […], but someone even brought a copy of a 1944 letter of free pass that was issued by the Swiss embassy for Jews at the time, and left it there."[14] For tourists, who would come to the square specifically because of the protests against the monument, these objects have become a genuine spectacle, and well into the summer organizers continued to bring objects to the site in order to hinder the monument’s construction. Since the middle of April, members of the group have organized afternoon discussions intended to function as a living commemoration of the events that took place 70 years ago.[15] The government has issued no statement regarding its views of the civil initiative, but rather continues to concentrate on the construction of the monument, the plans for which it evidently regarded as etched in stone. Orbán and his deputy Zsolt Semjén expressly defended the monument, as did the journal Heti Válasz (Weekly Reply), an unofficial media organ of the government. In his letter of 29 April 2014, which was intended for the larger public, Orbán characterized the composition as a sign of "creative bravura"[16]. According to him, "the pain of the loss of our sovereignty guides the builders of the monument."[17]

As a response to the concomitant positive assessment of the monument by Gábor Borókai,[18] the editor-in-chief of Heti Válasz, the journal published on 8 May an opinion piece by István Jelenits, a very influential Piarist friar, who is regarded as sympathetic to the current government. Jelenits regards the monument as confusing in its message: "If the people who designed the statue really intended to say what you have so delicately and circumspectly said, then one can hardly create a statue that expresses this complex message." According to Jelenits, "in order to shape the historical consciousness of a nation, we need not statues, but well-written history books."[19]

On 21 June 2014, a crowd estimated at 1000 people led by the internationally renowned conductor Ádám Fischer sang the Ode to Joy in protest against the still half-fnished monument.[20] The absurdity of Hungary's current political climate was only emphasized by the scene. How does singing the official anthem of the European Union count as an act of protest against a government-sponsored monument, when the prime minister himself once studied at Oxford thanks to the largesse of George Soros?

The answer to this question lies in the veiled anti-EU message of the monument, which is being used by the Hungarian government to attract voters. It is no coincidence that the extreme right-wing Jobbik party in Hungary, which is explicitly skeptical of the European Union, is the only party that supports the plans for the monument, with the additional demand that the monument on the other side of the square, which was erected in commemoration of the Soviet soldiers who died in the war, be demolished.[21] True, groups that are even more right-wing than Jobbik have opposed the monument's construction. According to them (and they refer to historical documents), the Hungarians and the Germans were allies, and the occupation of the country by the German army was actually undertaken in order to defend the country. On this point numerous historians agree.

In January 2014, the month the government's plans became public, István Deák, perhaps the most well-known and highly esteemed Hungarian historian in the United States and an emeritus professor at Columbia University, made a statement regarding the plans that anticipated the standpoint later adopted across the board by historians in Hungary. According to Deák, "the planned monument to the German occupation and the underlying notion of self-justification can cause serious damage to the country's image." But despite the damage being done to the image of the country abroad, Jobbik's strategy has been somewhat fruitful at home. As Deák observes, "what is going on in Hungary today, where the official leadership both apologizes for the sins committed by the Hungarian state against the Jews and points an accusatory finger at everyone but its own country, creates an impossible and dangerous public mood. It is infantile to perpetually accuse the West of conspiracy, to attack the United States with arguments once used by the nationalist Horthy and the Communist Rakes regimes, and to harbor perpetual grievances. The West is not rushing towards intellectual, moral, and financial bankruptcy; its main concern is surely not how to put the Hungarian people in chains."[22]

Historian Gábor Gyáni has expanded on this observation. Gyáni explains the conflict regarding the monument, a conflict which stems from the revival of the narrative of victimhood, as a product of the contradiction between the stance adopted by historians on the one hand and the incorporation of some individual collective memories in the official discourses on the other. According to him, the creation of a national day of remembrance on 4 June (the day on which the Trianon treaty was signed in 1920) goes hand in hand with the planned monument to German occupation because both commemorate a situation in which "the country, the nation – as a victim of the West – was abandoned by Europe." Gyáni continues: "According to the sculptor who designed the Szabadság tér monument and the [office of the] Prime Minister who commissioned it, the atrocities committed during World War II and, first and foremost, at its catastrophic end, threw the country into the camp of the victims. In other words, what counted as atrocities were crimes committed by foreign hands against the [Hungarian] nation."[23]

This narrative of victimhood and anti-Western sentiment complement each other well, and both can be manipulated by political parties to win votes. The official statement made in opposition to the monument by Germany, Hungary's most important ally from the perspective of foreign policy, was made in vain. The possibility of winning votes proved more important to the government (and in particular the possibility of winning votes from one of the most prominent new political parties, the extreme right-wing Jobbik party). The German embassy in Budapest did not mention in its statement that the eagle which figures in the monument as an embodiment of Nazi Germany is still part of the German escutcheon, but it did express its deep regret that the decision to build such a monument was made without any open discussion or debate.[24] If one accepts that Western powers are to blame, then one may understand the angel as representing a Euro-skeptical Hungarian people as a victim of Western capital and the imperial eagle as representing multinational corporations, among other things. Using skepticism regarding the European Union to curry favor with voters in Hungary today is hardly a difficult undertaking; and indeed Jobbik, which is appealing to some Fidesz voters, has been using this strategy to great effect.

One can discern traces of an interpretation of the monument as an expression of Euro-skepticism in the (somewhat illogical) advisory opinion endorsing its construction: "For a short time, we had a cozy, but submissive, relationship to [the Germans]. Our aggressive neighbor, which had a grand culture, made us believe in Europe, which until then had only figured in slogans. […] With the cooperation of its Arrow Cross nestlings [Nazi sympathizers in Hungary – S.H.] and accompanied by wholesale massacres, the Germany army murdered Hungary, and would have permitted it to survive temporarily as its slave."[25] The most important objection raised by critics of the monument was that it suggests that the Hungarian authorities played no role in the Holocaust in Hungary, although as any competent historian will note, the deportations that took place in the space of a few months in 1944 (the most rapid and devastating deportations of the Final Solution) could not have been implemented without the enthusiastic cooperation of the Hungarian government and populace.

There is no disagreement among Hungarian historians of the twentieth century regarding the shared German and Hungarian responsibility for the Holocaust in Hungary[26] The question of Regent Miklós Horthy's responsibility for the deportations is a recurrent topic of the banal debates that have been held by historians ever since the reburial of Horthy in 1993. Yet Horthy's responsibility for the deportations is indisputable (he was regent and de jure ruler of the country), even if some dubious historians do attempt from time to time to refute this fact. President Viktor Orbán and the Office of the Prime Minister have themselves often emphasized that the government at the time was responsible for the Holocaust (though Horthy's name goes unmentioned, presumably out of fear of losing voters). The problem, according to critics of the monument, is that the issue of Hungary's accountability is omitted entirely from the symbolism involved in its design. There is consensus on this not only among historians (both historians who are sympathetic to the government and historians who are sympathetic to the opposition), but also among representatives of Jewish organizations in Hungary. The monument portrays the Hungarian people as a unified figure, an angel with no internal divisions, that has fallen victim to Germany.

Róbert Hermann, a one-time classmate of Orbán's,[27] is one of the few conservative historians to have publicly criticized the plans for the monument, while at the same time being sympathetic to the government and enjoying the express support of the prime minister. "In my view," he has stated, "in its present form, the planned monument on Szabadság tér is not suitable as an attempt to repay our debt to the victims, since – as has been noted many times in this debate – it blurs the distinction between the victims and the perpetrators (or accomplices)." He also considers it important to emphasize that "the indisputable fact that no monument can meet every last interpretive expectation [this is one of the explanations often given by the government for its refusal to alter its stance – S.H.] does not mean that this portrayal, which involves an interpretation rejected by a significant group of the people affected, is the only possible solution." In other words, one cannot simply ignore the objections raised by the Hungarian Jewish organizations to the monument. Hermann, who is primarily a scholar of the 1848–1849 struggle for independence, currently holds an informal but very important position in the hierarchy of Hungarian historians. According to him, one solution to the conflict would be to use Szabadság tér as a space for some kind of monument to a moment in Hungarian history for which (as he correctly observes) there is no appropriate monument, namely the bloody suppression of the 1848–1849 Revolution. Angels could be used to represent Hungarians and the eagle could be transformed into the two-headed eagle of the Habsburg Empire.[28] This suggestion may seem ironic at first, but if one keeps in mind that the site itself (what today is Szabadság tér) was once the site of Neugebäude, a prison that embodied Austrian oppression in the eyes of the residents of Pest (it is referred to as the Hungarian Bastille), it does not seem merely flippant. Following the suppression of the Revolution, several thousand people who had participated in the fighting were held as prisoners in Neugebäude. The streets that lead to the square bear the names of Hungarian freedom fighters who took up arms against Vienna. Furthermore, Orbán himself saw 1848–1849 as a potential symbol of agreement and concord. In 2009, acting as a member of the opposition, he raised the following question at an exhibition opening: "Concerning 1848–1849, the question arises in each of us again and again: over and above the many polemical historical analyses, why do we all love the war of independence so unanimously?"[29] Perhaps an issue on which there is consensus is not useful as a means of winning votes and mobilizing a political base.

The roof of the multi-storey underground parking lot that was constructed at Szabadság tér by an Austrian builder in 2002–2003 was reinforced to allow for the erection of the monument. The eagle and the angel were constructed in secret. No member of the public so much as laid eyes on the angel's face before one hot Saturday night.

Shortly after midnight, on 19 July 2014, about one hundred police officers closed off the square. Budapest at the time was 'half empty', as it was the middle of summer holidays and most families had left the city for the countryside. Budapest's Capital Court had ruled against a referendum on the monument just a few hours earlier. The angel and the eagle were taken to the site wrapped in foil, and by sunrise the construction crew had completed their work. Most of the police officers remained at the site in anticipation of protests. There was one notable departure from the original plans. A ring was added to the eagle's leg with the inscription '1944', as if to make sure that passers-by place the monument in its proper historical context. Likewise, the national orb, which for centuries was a symbol of royal power, was placed in the angel's hand. The objects that comprised the Living Monument were left in the area surrounding the statue. The next day another demonstration was organized against the statue, and some protesters even threw eggs at it, but the statue was surrounded by a barrier and a wall of police.[30] To this day the statue remains guarded by police around the clock. No demonstrations have been held at the site of the monument since autumn 2014, but what appear to be innumerable protests have been organized against the corruption of the Orbán government, which won the elections with a decisive majority.[31] The angel almost seems to have fallen captive to the police who stand guard and to the objects that were placed at the site in gestures of protest.

According to the official description of the monument, "We do not know whether [the angel] is sleeping, dreaming, or daydreaming. The composition indicates that the dream is turning into a nightmare." One has the feeling one is reading a prediction (hopefully mistaken) regarding the future of debates in Hungary on the politics of memory.

The construction on Budapest's Szabadság tér in Budapest of a monument to the German occupation of Hungary was undertaken without any prior public discussion. Even today, what discussion there is takes place primarily between the government and professional and civic organizations. One of the issues at stake is whether future such monuments will or will not simply serve as pretexts for (or allegories of) political conflict. Hungarian historians are in widespread agreement that the thinly veiled message of the monument is a distortion at best. As a political statement, however, it builds not only on discourse around the politics of memory in public life and the need for national self-justification, but also on the prevalent anti-European Union sentiment of Hungarian voters, as well as their disappointments and their susceptibility to narratives of victimhood. The Hungarian government nonetheless insisted on carrying through with the monument's construction in spite of arguments raised by the professional and civic organizations, since in doing so it hoped to win votes to solidify its base. Prior to local government elections scheduled for autumn 2014, this was particularly important, especially in Budapest, where Fidesz garnered the fewest per capita votes compared to the national average. From all of this, one might retain the impression that both history and historians have served merely as ornaments on the government's anti-democratic enterprise in building this monument to the German occupation. It might appear that they functioned as little more than irritating background noise during the discussions that took place between politicians. One might notice how easily they were ignored by the political faction currently in power as it proceeded, for the sake of its own narrowly conceived political interests, to erect a monument that ultimately commemorates the denial of the past.

Sándor Horváth: Goodbye Historikerstreit, Hello Budapest City of Angels: The Debate about the Monument to the German Occupation. In: Cultures of History Forum (12.04.2015), DOI: 1025626/0037.

Copyright (c) 2015 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

Ágoston Berecz · 18.01.2021

The Trianon Ramp and the Obstinate Memory of a Magyar Greater Hungary

Read more

Katalin Madácsi-Laube · 28.06.2020

A New Era of Greatness: Hungary‘s New Core Curriculum

Read more

Emily Gioielli · 07.02.2020

From Crumbling Walls to the Fortress of Europe: Changing Commemoration of the ‘Pan-European Picnic’

Read more

Kata Bohus · 31.10.2019

Éva on Insta: Holocaust Remembrance 2.0

Read more

János Gadó · 16.08.2019

The Splendour and the Misery of the House of Fates

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).