18. Dec 2020 - DOI 10.25626/0123

Jakub Vrba is a PhD student at the Institute of Economic and Social History, Charles University in Prague. His research interests include the history of the Czechoslovak Communist Party, nationalism in former Czechoslovakia before 1945 and the politics of memory in the Czech republic after 1989.

The statue of Soviet Marshal Ivan Stepanovich Konev, who commanded the Red Army troops that liberated Prague in 1945, was removed from one of Prague’s squares on the 3 April 2020. The removal took place during a lockdown implemented by the Czech government due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Ondřej Kolář, the mayor of the local municipality Prague 6 and a member of the pro-European and liberal-conservative party TOP 09, ordered the statue’s removal. Referring to the present crisis, he jokingly remarked on his facebook page that Konev “did not wear a mask, which is prohibited.” However, the removal was no joke; neither was it the spontaneous decision of only one person. On the contrary, the Konev monument has long been an object of contestation and dispute and has indeed become a symbol of the diverse, even contrasting collective memories in Czech society. Moreover, the monument has been frequently used as a vehicle for both international and national politics. This article will summarize the political debates surrounding this monument against the backdrop of the Czech Republic’s recent politics of history. Moreover, it will try to shed light on the question of why this debate has surfaced now and why the statue – as well as many other monuments to the Red Army across the country – have remained in place for so long, particularly when similar memorials were dismantled in many other countries of the region.

Although Marshal Konev had been made an honorary citizen of Prague in 1945, the plans to build a statue of him only began to materialise in the 1970s. The Square of the International Brigades,[1] not far from the headquarters of the former Czechoslovak People’s Army and the Prague Castle, was chosen as the appropriate place for this. The statue was made by the Czech Artist Zdeněk Krybus and was unveiled by prominent communist party officials in April 1980 on the anniversary of the Liberation of Prague and the End of the Second World War.[2] As a commentator emphasized in a 2019 TV reportage about the event, it was Konev who “liberated us”, Czechs and Slovaks, from the German occupation. This message was coherent with the official narrative at the time according to which the legitimacy of the communist regime was built, that is, on the outcome of the War in Czechoslovakia, the socialist economy and the expulsion of the Czechoslovak Germans. According to this narrative, it was the Soviet Union, together with the Czechoslovak communist resistance, that liberated Czechoslovakia from Nazism; the role of the Western allies and the non-communist anti-Nazi resistance was marginalized. Representatives of the Soviet military were present during the unveiling ceremony, which underlined another aspect at the time: namely, the need to portray the Red Army (and with it, the Soviet Union) in a favourable light after the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact countries in 1968.

After the Velvet Revolution in 1989, this communist narrative was largely reversed. With regard to the Second World War, emphasis was placed on the role of the Czechoslovak exile government in London, and the Czechoslovak pilots of the Royal Air Force and the so-called democratic (non-communist) resistance were cast as the heroes. The US Army was celebrated as the liberator of the west Bohemian city, Pilsen; the liberation of Prague by the Red Army was somewhat downplayed by those who emphasized the important role of the Russian Liberation Army (the so-called ‘Vlasov Army’), a formation of Russian anti-Soviet defectors in the German Wehrmacht that supported the 1945 Prague uprising shortly before the Red Army entered Prague. The most radical voices even portrayed the arrival of the Red Army as the beginning of a new occupation. However, this kind of historical revisionism was not as strong as, for example, it was in the Baltic states or in Poland, as the sacrifice of the ordinary Soviet soldiers in their fight against Nazism still remained a part of the historical narrative on the Second World War.

This may be one of the explanations for why many of the statues that commemorated the Red Army remained in place, despite the shift in historical interpretations and narratives after 1989. Yet, other monuments associated with the recent communist history were dismantled. For example, almost all monuments connected to prominent figures of the Czechoslovak Communist Party were removed. In 1991, the Czech Artist David Černý painted a Soviet tank, which had allegedly entered Prague in April 1945, pink; it was a symbolic act that became widely known across the country.[3] Later, the tank was removed altogether. But this is one of very few cases ridiculing the Red Army liberation narrative in which the memorial was removed. Other statues of Soviet soldiers (e.g. the one near Prague’s main train station, or the Marshal Konev monument) have until recently remained in place. In the post-1989 Czech politics of memory there seems to have been an agreement to separate the memory of the Red Army’s sacrifices and liberation of the country from the strictly negative historical narratives and public representations of the communist past. The reason for the more cautious politics vis á vis the memory of the wartime Red Army was not only due to historical facts, but also legal and ethical concerns regarding to the treatment of Soviet war cemeteries and memorials as well as diplomatic concerns to maintain sustainable relationships with the Soviet Union and later the Russian Federation.

So, what has changed that we are now witnessing a convergence of the radical anti-communist memory politics and the more positive public commemoration of the Red Army? Firstly, the Russian Federation’s foreign policy has become more aggressive under Putin’s second administration, and the annexation of Crimea, along with the war in Donbass, have undoubtedly worsened the relations between Russia and other states in Europe, including the Czech Republic. Secondly, both governments and opposition across the region have turned more to anti-immigration stances, populism and Euroscepticism in order to gain political ground. In the Czech Republic, this development is best represented by the ANO movement under its leader and current Prime Minister Andrej Babiš, which has become a dominant political force over the past few years. Interestingly, Babiš’s 2017 cabinet was the first Czech government since 1989 that was openly tolerated by the Communist Party fraction in parliament. President Miloš Zeman, who was re-elected in 2018, has long been known for his Machiavellian realpolitik and his pro-Russia stance. These leaders tend to ignore rather than actively challenge the symbolic, anti-communist grammar of the liberal transformation years; they nevertheless contribute to the current reshaping of historical narratives and official representations of history in the public.

However, the anti-communist rhetoric still appears to be a mobilizing force among supporters of the so-called ‘democratic opposition’ which includes the liberal Pirate Party, the economically liberal, national-conservative and Eurosceptic Civic Democrats (ODS), the liberal-conservative TOP 09 and the Christian Democratic KDÚ-ČSL. The mass anti-government demonstration in Prague which was held on the thirtieth anniversary of the Velvet Revolution, clearly “emphasized continuity between the struggles for freedom and democracy in 1989 and the present,” and it attracted more than 250,000 people.[4] One of the many issues against the government that were brought up during this mass demonstration (the largest since 1989) was Babiš’ suspected past as an agent of the communist-era secret police (StB). The event might serve as a good illustration for the extent to which the use of anti-communist symbolism still works as a tool of protest mobilization.

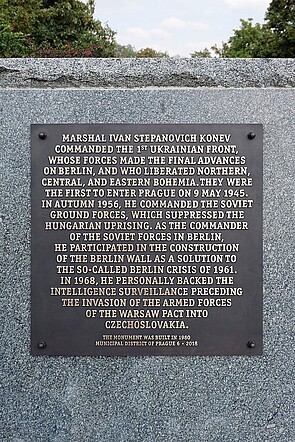

The renewed debate over the fate of the Konev statue needs to be seen in the context of discursive shifts and the changing politics of memory. The first impulse came from an incident in which an unknown person threw a canister of pink paint over the statue in 2014 – probably meant as a reminder of the above-mentioned Soviet tank that was vandalized in a similar way. Subsequently, two groups of activists emerged, one demanding the removal of the statue, the other its protection. The local municipality did not want to remove it, but rather decided first to clean the statue and eventually to refurbish it.[5] In the meantime, the municipality was determined to alter the meaning of the monument by adding a plaque which stated that Konev’s forces “liberated” Prague; yet, it also mentioned the fact that the Soviet Army under his command “suppressed” the Hungarian uprising of 1956, it mentioned his role during the Berlin crisis of 1961, and further, that he “personally backed the intelligence surveillance preceding the invasion” of Czechoslovakia in 1968.

The plaque, unsurprisingly, did not resolve the contentions. On the contrary, it rather intensified the dispute about the monument’s future – both during public demonstrations around the statue and in public media debates. In 2019, there were several incidents in which protestors vandalized the statue with paint. After some failed attempts to clean the statue, the municipality decided to stop cleaning, which in turn motivated pro-Konev activists to do the job and polish it. Soon after that, on the fifty-first anniversary of the Warsaw Pact invasion, someone wrote “bloody marshal” and the years ‘45, ‘56, ‘61 and ‘68 on the monument. When the local council subsequently decided to hide the statue behind a tarpaulin, some activists tried to dismantle it.

There were also several suggestions to transfer the statue to another location. Former Slovakian prime minister Ján Čarnogurský wanted to bring it to Banská Bystrice, Museum of the Slovak National Uprising.[6] Konev’s daughter agreed to having the statue moved to the Prague’s Olšanské hřbitovy where there is a Soviet military cemetery.[7] The municipality eventually decided to give the monument to the newly created the ‘Museum of 20th Century Memory’,(Museum pamĕti XX století) founded by the Prague city council in 2019. According to its statutes, the museum is tasked with preserving “the historical memory about key events of the twentieth century, that relate to the origins, existence and the fall of the totalitarian regimes on the territory of Czechoslovakia”. Historian and member of the managing board Petr Blažek is quoted in the online platform Praha.eu suggesting that the new museum should be inspired by the Museum of the Warsaw Uprising, the Museum of the Second World War in Gdansk, the House of Terror in Budapest or the Topography of Terror in Berlin – four rather remarkably different institutions.

If we look closely at the arguments, we can see that the proponents of a removal of the statue formed a compact coalition which included many oppositional politicians, both liberal and conservative. Their main point, to put it simply and to paraphrase the title of one article on the conservative server Echo24, was to tell “the truth about Soviet Marshal Konev”. That “truth” included Konev’s previously mentioned involvement in the politics of the Soviet Union. Mayor Kolář also pointed out on Czech TV, that the moving of the statue to the new museum should “contribute to an objective interpretation of our recent history.” Many others stressed that they want to honour all Soviet soldiers that liberated Europe, but not the Soviet leaders.[8] The mayor of Prague, Zdeněk Hřib from the Czech Pirate Party, described the Konev statue in an interview as a “monument of Czech servility”. In this sense, taking down the monument would be a form of liberation of the Czech nation. Eight relatively well-known Czech historians supported a similar notion. In a written statement published in an online platform, they called Konev “one of Stalin’s butlers”, whose monument was an “expression of servility” of the post-1968 normalization regime towards “the occupying power.” Supporting this argument, they quoted The History of Russia in the 20th century, edited by Russian historian and Putin-critic Andrey Zubov – a book whose narrative is based on Russian orthodox nationalism and strict anti-communism.

The controversy was not just about removing the Konev monument; it was equally about erecting a new one. In 2019, Pavel Novotný (ODS), mayor of the Prague suburb Řeporyje and former tabloid journalist, decided to build a monument for the Vlasov Army, thereby symbolically diminishing the role of the Soviet Army during the Prague Uprising. His attempt to defend his plan on Russian state TV went viral on YouTube. The new monument was unveiled in April 2020 and consists of a small stainless-steel tank with a helmet covering the turret. The designer of the monument is officially unknown, but some journalists have speculated that it was David Černý, the same artist who painted the Soviet tank pink in 1991.[9] The plaque beneath the monument states that the operations by the Vlasov Army incite “many controversies” but that it is an “undeniable historical fact” that these men helped in the Prague Uprising. Again, this is supported by reference to a Russian author, this time Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who wrote in The Gulag Archipelago: “Have all the Czechs understood which Russians saved their city?”[10] The reference to Solzhenitsyn is probably supposed to underline that the criticism is aimed against the Russian government or pro-Russian Czech politicians, not against the Russian people (at least, not explicitly).

The first time the Russian embassy weighed in on this controversy was in 2018 when Russian officials threatened that the memorials of Czechoslovak legionaries in Russia from the First World War could be also damaged.[11] Both the words of the Russian Federation’s Minister of Culture Vladimir Medinsky, who called mayor Kolář a “Gauleiter”, and the attempts of the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation to sue mayor Kolář caused an uproar amongst the Czech public. Medinsky and the actions of the Investigative Committee were condemned by nearly all Czech politicians, including Andrej Babiš and Miloš Zeman. Jiří Pospíšil, former chairmen of TOP 09 and member of the European parliament, called them “scandalous” and stressed that “Russia forgets again that the Czech Republic is an independent country.”[12] The controversy turned rather bizarre when the Czech magazine Respekt claimed in a 2020 article that Kolář, Hřib and Novotný are under police protection because a suspected Russian intelligence agent, travelling with a diplomatic passport, was said to have arrived in Prague carrying the lethal poison ricin in his luggage. However, it was later revealed that the “poison plot” was a hoax, likely the result of an internal power struggle between Russian embassy employees in Prague.[13]

The fiercest most obvious opponents to the removal of the statue were the Czech communists who repeated the communist-era antifascist narrative they had known from the period before 1989. In a public statement issued by the Executive Committee of the Communist Party, the party declared that “certain political circles” were trying to “rewrite history” and that their goal was to prepare Czech society for another push by the Sudeten-German Landsmannschaft and further to “tighten the military and economic relationship with big states in the EU and with the USA.” The KSČM even provocatively suggested removing Prague’s Churchill statue as well.[14] As was to be expected, President Zeman and former president Václav Klaus also chimed in, both well-known for their good relationships with Russian politicians. Zeman repeatedly opposed the removal and stated that like other monuments to people “who helped to liberate our nation”, the Konev statue has to remain in Prague. Calling the statue’s removal an iconoclasm, he nevertheless also criticised the Russian officials’ reaction to it. More radical was Zeman’s press secretary who wrote on Twitter that Kolář´s party TOP 09 should rather be called NSDAP 09 and that mayors Kolář and Hřib are “faces of new totalities”. Klaus called the removal of the statue the “cowardly” actions of an “aggressive group of delayed fighters against communism.”

Chairman of the Czech Social Democratic Party and vice-Prime Minister Jan Hamáček chose a more moderate approach. According to him, it was “too late to remove Konev”. In an interview to the daily Deník he argued that if this statue was removed, we could also discuss the role of Bohemian king and Roman emperor Charles IV, or Hussite commander Jan Žižka. Criticism did not just come from politicians. Jan Tesař, a prominent Czech historian and former dissident, wrote an open letter to the Russian ambassador and vehemently opposed the removal. According to him, it was evident “that the recent anti-Russian rhetoric is not about history but about a political campaign with monuments.”

Due to the involvement of the Russian Federation, the Konev controversy quickly transformed from a domestic to an international affair as international newspapers, including The Guardian and The New York Times, reported on the matter. However, the dispute was also influenced by other outside impulses. Just months after the removal of the Konev statue in April 2020, an event that the Communist Party proposed early on nearly took place. Two activists defaced the Churchill statue in the Prague district of Žižkov by writing on it “He was a racist” and “Black lives matter”. The statue is a copy of the Churchill monument in London and was unveiled by Václav Klaus and Margaret Thatcher in 1999.[15] Between 1977 and 1990, a statue of the second communist president Antonín Zápotocký stood on that same square. Inspired by the global Black Lives Matter movement, the activists, in their response to media inquiries, recapitulated Churchill’s policy in the British colonies and stated that racism “is not a remote problem, which is pulled here from abroad; the Czech approach towards Roma people or to refugees is living proof” that it is a local issue.

Some in the Czech media quickly connected this incident with the Konev controversy. The newspaper Deník asked Jiří Ptáček, Mayor of municipality Prague 3 from TOP 09, whether Churchill could follow the fate of Konev and be removed from the square. Ptáček denied it vehemently. Zeman and Klaus both also compared Churchill to Konev in various interviews, and said that both helped to liberate the Czech nation. Representatives of the oppositional parties either implicitly or explicitly denied this comparison, and the claim that Churchill was a racist. Jiří Pospíšil from TOP 09 wrote on Twitter, that the former British prime minister was a “great politician and statesman who fought against the biggest racist in the modern history of humankind.” Likewise, Petr Fiala, chairman of ODS, tweeted that the act was “stupid and shameful”; he acknowledged that racism could be a problem but, according to him, racism “in the Czech Republic does not have a strong basis or support.” Whereas, according to some commentators, the Konev controversy exhibited the danger from the East, the Churchill controversy exemplified the danger from the West. As Alexandr Vondra, a former dissident and current member of the European Parliament for ODS, commented on his personal website that the Churchill statue in London was defended by the football rowdies against the “leftist hordes” and he warned that George Washington or Martin Luther could be considered racists by the leftist activists as well. “Where is the West heading? (…) Here [in the Czech Republic] it is still not so serious. But if we take into consideration how quickly this trend is spreading from the West to us, we have something to look forward to,” wrote Vondra. This view is not unique, and similar comments, albeit in a different context, could be heard from both the former President of the Senate Jaroslav Kubera (ODS) and the recent Speaker of the Chamber of Deputies Radek Vondráček (ANO). They argued that Western (neo)Marxism or any progressive views are more dangerous than the Czech Communist Party.

Presently, in December 2020, the story of the Konev monument is far from over. The statue is in the possession of the prospective the Museum of 20th Century Memory as their first artefact. No one knows how the future exhibition in which the statues should be displayed will be like, although the ideological background of the institution is already becoming recognizable. The museum’s director recently suggested giving the statue to the Russian Federation in exchange for archival documents relating to the death of the former Czechoslovak minister and son of the first Czechoslovak president Jan Masaryk, who probably committed suicide after the 1948 coup d´état. Whether or not this was enforced or otherwise provoked by the Soviet secret police is still being debated among both historians and politicians. The municipality is also planning to place an outdoor exhibition in the square where the Konev statue stood; in the long run, a new monument dedicated to the liberation of Prague is supposed to be built. However, the form of this monument is not known yet.

The Konev controversy has taken place in a divided society where the supporters of the opposition, with their stronghold in Prague, see the government as pro-Russian and ex-communist. It was likely further stimulated by the opposition’s fear that the anti-communist consensus of the earlier decades was starting to erode[16] and by a growing concern surrounding the Russian Federation’s aggressive foreign policy towards neighbouring countries. The statue’s removal from its prominent place in the centre of Prague, in a way, epitomizes the discontinuance of a previously existing informal agreement to separate the commemoration of the Red Army from the wider, more aggressively anti-communist memory politics.

The controversy also confirms that the communist past is still a relatively important topic amongst the Czech public. It seems that anti-communist rhetoric is a recognizable, mobilizing force – at least, for some parts of society – and a tool that can be used against the government to help the (otherwise ideologically rather heterogeneous) opposition to find common ground. It would be interesting to further trace the form of this contemporary (now oppositional) anti-communism that, as we have seen, does not always have to be liberal or pro-European.

The reactions to the defacement of the Churchill statue seem to point to the fact that it is not just the communist past, but also the Second World War that remains a sensitive subject in the Czech collective memory. These reactions show how quickly the different political camps can reorganize, and how former enemies can become allies (albeit with different implications for both domestic and international politics). Something similar could happen with regard to other controversial issues in the collective memory of the Second World War, like, for example, the role of the Czech Protectorate officials during the Holocaust, or the expulsion of the Czech Germans. Yet, most likely, the Czech ethnic nation in its fight against Nazism would remain the unquestionable hero in any narrative contestation in today’s Czech Republic, regardless of one’s political view or (anti)communist stance.

Jakub Vrba: Monumental Conflict: Controversies Surrounding the Removal of the Marshal Konev Statue in Prague. In: Cultures of History Forum (18.12.2020), DOI: 10.25626/0123.

Copyright (c) 2020 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

Patrick Metzler · 21.12.2022

Localizing “Our Germans”: The New Permanent Exhibition in Ústí nad Labem

Read more

Veronika Pehe · 11.05.2022

‘The Nineties’ on TV: Remembering the Transformation Era in Czech Popular Culture

Read more

Jiří Smlsal · 25.01.2022

The Stench of Pigs and the Authority of Historians: Czech Debates About the Lety Concentration Camp

Read more

Karolína Bukovská · 25.11.2021

(Re)construction of Czech History: The National Museum and its New Permanent Exhibition on the Twent...

Read more

Veronika Pehe · 21.07.2021

Czech Prime Minister Implicated as Communist Secret Police Agent – Yet Nobody Cares

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).