12. Aug 2023 - DOI 10.25626/0147

Alexandr Voronovici obtained his PhD in contemporary history from the Central European University (CEU) in Budapest and has worked as lecturer and researcher at CEU as well as the Higher School of Economics in Moscow. His research focuses on the history of East European, in particular in contested borderlands. Currently a fellow at the Imre Kertész Kolleg in Jena, Germany, he works on memory politics in the post-Soviet de facto states.

On 11 May 2022, almost three months after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the leaders of the pro-Russian Donetsk People’s Republic (DNR) – at the time recognized by Russia, but not yet fully annexed – participated in the inauguration of a monument in Shakhtarsk dedicated to Alexander Zakharchenko, the former leader of the separatist republic. It is telling that, even under the circumstances of a full-scale war, the DNR’s current leader, Denis Pushilin, and the chairman of its People’s Soviet (Council), Vladimir Bidyovka, found the time to attend the event. It highlights the political importance assigned to matters of public memory by the leadership of the breakaway region. Zakharchenko had regularly made historical references in his declarations, and proclaimed 2018 to be the "year of the history of Donbas" in the DNR. After his assassination in 2018, he himself became the object of memory politics, as his image was instrumentalized, constructed, and glorified by the separatist regime.

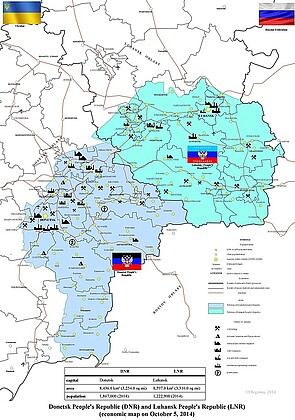

In the following, I will briefly outline some of the trends in the political instrumentalization of the past in the two separatist Donbas republics in Ukraine, with an emphasis on the relatively peaceful part of their history. Between the signing of the Minsk II agreement on 12 February 2015 and Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 (and the subsequent annexation of the two breakaway regions on 30 September 2022), the relative quiet of the armed dimension of the conflict with Kyiv, despite the continuation of low-intensity military clashes, gave the secessionist regimes in the DNR and the LNR (Luhansk People’s Republic) the opportunity to consolidate and engage in a relatively comprehensive process of state and nation-building.

The leadership of the DNR was much more active than that of the LNR in instrumentalizing the past, more frequently making historical claims in official declarations and starting with the production of new history textbooks earlier. As such, most of the examples here are from the DNR. Nevertheless, the wider tendencies in the evolution of the politics of history in these two separatist republics are largely the same. Although, for the sake of convenience, the present line of argumentation largely follows a stage-by-stage narrative structure, one should not treat these stages as clear-cut periods with fixed temporal borders. The goal is rather to capture some of the dominant tendencies in the politics of history which were also often framed by changing internal and external dynamics. In many respects, the outlined – sometimes competing, sometimes mutually reinforcing – discourses and narratives coexisted as certain discourses came to the fore or, on the contrary, were marginalized.

To what extent the politics of history — and, more broadly, state and nation-building – in the Donbas separatist republics was controlled by Moscow is a matter of debate; without inside knowledge, it is hard to determine with any certainty. Available sources such as the so-called “Surkov leaks” provide some insight into the relations between the separatist republics’ leaderships and their Moscow supervisors, not least with regard to the uses and abuses of history for various purposes.[1] According to these and other sources, local leadership seemed to have retained a certain degree of autonomy, driven in part by the existence of competing groups in the Donbas republics, as well as various political and administrative circles in Russia competing over the control of power and resources in the DNR and the LNR.

The ‘Novorossiya’ – which can be translated as ‘New Russia’ – project dominated the early phase of pro-Russian separatism in Eastern Ukraine after 2014. ‘Novorossiya’ refers to the eighteenth and nineteenth century Russian imperial expansion into the territories of the present-day Southern and Eastern Ukraine. Marlene Laruelle has demonstrated how the Novorossiya project became a magnet for political groups and activists with different ideological paradigms: “red” (Soviet), “white” (Orthodox), and “brown” (fascist).[2] Yet, these attempts to use certain symbols to inspire pro-Russian movements or upheavals in other Southern and Eastern regions of Ukraine ultimately failed, which led to the gradual “freezing” of the Novorossiya project. Instead, a different narrative gained traction that focused more on the regional specificity of the multi-ethnic Donbas, rather than emphasizing the Russian dimension. Although this discourse had emerged much earlier (to some extent even before 2014), it only took hold with the settlement of the borders of the DNR and the LNR and the signing of Minsk II Agreements in 2015.

A crucial step in constructing the historical legitimacy of the DNR was the declaration of a Memorandum of the Donetsk People’s Republic on the Principles of State-Building, Political and Historical Continuity on 6 February 2015. The DNR proclaimed itself successor to the Donetsk-Kryvyi Rih Soviet Republic (DKRSR), a “multi-national people’s state”, as well as its traditions. The DKRSR was a short-lived Soviet republic established in 1918, one of many that were declared on the territories of the former Romanov empire during the civil war. It claimed a large part of present-day Eastern Ukraine including Donbas, Kharkiv, Dnipro. To what extent it controlled any of the territories it claimed is a matter of debate. During the chaotic years of the civil war, many polities and governing bodies were proclaimed, but not all of them actually exercised much authority beyond paper documents.

For the DNR leadership, though, the uncertainty of the DKRSR’s historical record mattered little. The memorandum claimed the continuity of the DKRSR ideas, seeing their continuation through the pro-Soviet “Interdvizhenie” movement in Donbas in the late 1980s,[3] the regional referenda on the federative structure of Ukraine and on language issues in 1994, the failed attempts to organize a new referendum on the status of the region in 2004, the establishment of the “Donetsk Republic” political movement, and, finally, to the 2014 referendum. In this way, the recently declared separatist republic acquired a historical lineage of a “naturally” emerging Donbas statehood that stood in contrast to any accusations of the artificiality of the secessionist polity.

The DNR People’s Council adopted this memorandum just a few days before the Minsk II negotiations. Evidently, its historical argumentation was an attempt to bolster the legitimacy and positions of the DNR leaders, but also hints at a historical justification for expansion. Hence, the memorandum called “for cooperation and unification of efforts to build a federative state on a voluntary basis of all the territories and lands that were part of the Donetsk-Krivoy Rog Republic” which extended far beyond those territories controlled by the separatists at that point.

The memorandum[4] signified more than just an attempt to exert pressure on Ukraine and the international actors who participated in the negotiations in Minsk. The emphasis on the “multi-national” character of the DKRSR republic was not accidental: After the failure of the Novorossiya project, which – despite attracting a heterogeneous group of sympathizers – retained Russian nationalist and Russian imperial connotations, it became obvious that a simple Russian (imperial) nationalist message could not gain sufficient traction among the population of Southern and Eastern Ukraine. The territorial expanse of the separatist republics and the necessity of carrying out state-building within parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts also favoured a narrower focus on Donbas and its regional specificity, rather than on the wider territory stretching from Donetsk all the way to Odesa (which would roughly correspond to the imagined geography of Novorossiya). The focus was now on the national and cultural diversity of the Donbas throughout history, discursively constructed as a unique feature of the region, justifying its secession from the “(ultra)nationalist” central government in Kyiv.

It should be mentioned that, before 2014, the majority of the population in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions of Ukraine identified themselves as Ukrainians, even though the Russian language dominated, especially in urban areas. The separatist regimes did not control the entirety of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. Yet, the shift in the politics of history was to some extent intended to be more inclusive and thus attractive to the culturally heterogeneous Donbas, boosting the internal legitimacy of the separatist regimes. Such an inclusive attitude to the titular group of the parent state was quite specific, if we compare Donbas to other separatist regions. There are similarities with the secessionist Transnistria on the left bank of the Dniester in the Republic of Moldova; elsewhere, I have somewhat ironically suggested that it is possible to conceptualize such an approach to the politics of history in Transnistrian and Donbas secessionist polities as “internationalist separatism”.[5]

To some extent, the separatists were maintaining the approach of the sitting regional government and their representatives before 2014. Before the 2013-2014 crisis and the mass demonstrations against President Victor Yanukovych and his government, local leaders often used the discourse of the Donbas’s historical uniqueness for their electoral campaigns on both the national and regional level, in order to maintain their grip on power in Ukraine’s East. Nevertheless, the new conditions and goals of the separatist regimes in the DNR and the LNR gave that discourse a new impetus and meaning. Similar narrative tropes and symbols acquired different importance, accents, and content, seeking to not only to frame the Donbas as different and unique within a united Ukraine, but to justify secession and to legitimize – internally and externally – the separatist regimes in Donetsk and Luhansk.

The separatist regimes attempted to construct the historical narrative of a “Donbas people (Narod Donbassa)” as a multi-ethnic community with historical traditions of interethnic tolerance and a rejection of ethnic nationalism. In this narrative, the Donbas separatist leaders portrayed themselves as a more democratic and tolerant alternative to the “(ultra)nationalist” central government in Kyiv. In a way, there was also a certain mimicking of the Western discourse of diversity and multi-culturalism, but partially framed within the tradition of Soviet internationalism and Russian civilizational discourses.

To be sure, not all separatists rejected the ethno-national argument. Some saw the very existence of a sizeable, allegedly oppressed, ethnic group different from the titular nation as reason enough to call for secession. The narrative construction of a “multi-ethnic Donbas” thus required additional arguments, and those secessionist leaders who considered it to be the more compelling narrative more often than not referred to history in order to make their point. Moreover, this multi-national narrative fit well with the Minsk II agreement framework that, among other things, presupposed the eventual reintegration of the Donbas separatist republics on terms favourable to Russia and Russian-backed separatists. In that context, maintaining connections to other regions of Ukraine could have its benefits. For Russia, the ultimate goal was to use the separatist republics to exert influence on the entirety of Ukraine, possibly also constructing the image of an alternative pro-Russian Ukraine.

In 2018, DNR authorities sought to further institutionalize this narrative of a “multi-national Donbas” with a new history textbook entitled History (History of Donbas from Antiquity to the Present Day) written and designed in Donetsk for university education. The editors of the textbook – historians Larisa Shepko and Vladimir Nikol’skiy – emphasized the "multi-national character of the region […] which representatives of each people have contributed to."[6] Moreover, they noted that,

during the twentieth century, in the Donbas, a stable interethnic community has developed, speaking Russian, with common values, cultural features, a clear regional sense of self, identity and a firm sense of ethnic and religious tolerance. […] The inhabitants of the region are a stable interethnic community (and not a separate ethnic group). At the same time, the regional identity absolutely dominates over the ethnic one.[7]

The fact that this statement appears in a separate section of the book explaining the essence of the Donbas’s “interethnic community” suggests that the authors understood that the historical narrative of the multi-national character of the community was not necessarily that obvious, even to the population of the region itself, and may be much more difficult to internalize than narratives that focused on ethno-national communities.

Indeed, this rather inclusive narrative was not uncontested; nor should one overemphasize its impact and rootedness. The separatist leaders deployed the multi-ethnic historical narrative rather instrumentally, to suit the circumstances and goals of the self-proclaimed republics in Donbas. Moreover, notions of inclusivity in the promoted historical narratives quite easily coexisted with repressive measures against political opponents and the dominance of Russian culture, language, and symbols. But even the narrative of the Donbas’s “historical traditions” of multi-ethnicity and tolerance contained a number of pressure points, the most problematic being the issue of whether and how to include ethnic Ukrainians and Ukrainian culture.

The separatist discourse attempted to make a clear distinction between the allegedly “pro-Russian” and non-nationalist East and South of Ukraine and the “(ultra)nationalist” and repressive West, including the central government in Kyiv. This narrative distinction had certain symbolic advantages, as it boosted the legitimacy of the Donbas separatist cause, highlighting that the “nationalist” Ukrainian government was alien not only to the people in Donbas, but also to other regions of Ukraine. In this way, separatist leaders and Moscow also hoped to exert influence on the population that remained under the control of the Kyiv government. At the same time, separatism was framed as necessary to defend Russians and Russian speakers from Ukrainian nationalism, giving the symbolic inclusiveness towards Ukrainians a somewhat ambiguous character. The recurring debates about the possible renaming of Taras Shevchenko Boulevard, a central artery in Donetsk, named after the Ukrainian “national” poet, was one example of this ambiguity. Similarly, the fate of the Shevchenko monument situated on that boulevard not far from the intersection with Alexander Pushkin Boulevard, named after the Russian “national poet”, was another contested issue.

In the DNR, the inclusive discourse towards Ukrainians was criticized by some opposition groups. For example, the former self-proclaimed “People’s Governor” of the Donetsk region, Pavel Gubarev, often positioned himself as a defender of a more pronounced Russian ethnic narrative and representation of the Donbas. In his programme, prepared for the election of the head of the DNR in 2018, he clearly opposed the inclusive politics of memory pushed by the then governing elites of the DNR, noting that,

the educational and cultural institutions of the Republic will be finally cleared of the ideology of Ukrainianism hostile to historical Russia and will be conductors of an all-Russian identity. […] Under our close attention [...] the education of young people will be in the spirit of Russian national values.

Moreover, this Russian ethnic narrative could also be found in yet another history textbook approved for university education by the DNR Ministry of Education and Research on the exact same day in 2018 as the textbook quoted above.[8] The title alone, History: Donbas in the Context of the Development of the Russian State, already suggests a different approach as it uses the term russkiy and not rossiyskiy state. Rossiyskiy usually refers to Russia as a state, while russkiy has more ethnic and cultural connotations. These concepts are however contested and constantly renegotiated.

It should be noted that this choice of phraseology and terminology in favour of russkiy state in relation to the modern period was unusual even in the context of the Russian Federation at that time. This phrase was borrowed from the repertoire of various Russian nationalist and some of the monarchist groups. The content of the textbook largely follows the declared title. In the introduction, the authors emphasize that one of the tasks of the textbook was to instil "a sense of patriotism, love and pride in one's Motherland and the Russian nation."[9] The use of the phrases "Russian nation" and not simply "Russian people" or even "Russian national state" emphasizes the textbook's overarching nationalist narrative frame. To some extent, the use of the adjective "Russian/russkiy" in this context does not unequivocally exclude the inclusion of other groups. Nonetheless, nowhere in the textbook – in contrast to the other one mentioned above – do the authors emphasize the “multi-nationality” of the population of Donbas or its subjecthood as a multi-ethnic community.

The coexistence in the DNR of two textbooks with different conceptual frameworks underscored the presence in the region of different narratives about “Russianness” and the dominant identity of the local population in the region, as well as the ambiguity of understanding orientation towards Russia and the potential unification with it. Nevertheless, it was the textbook, built around the narrative of the “multi-nationality” of Donbas, that was taken as the basis for the development of school history textbooks, which were gradually introduced beginning in fall 2019.

A narrative shift in terms of the symbolic inclusion of Ukrainian culture and language in the history and presence of the separatist republics occurred in the early 2020s. A major symbolic gesture in that regard was the declaration – on 6 March 2020 in the DNR and on 3 June 2020 in the LNR – of the Russian language as the only state language in the separatist polities. Before that, Ukrainian had been declared the second official language in the Donbas republics. In reality, that distinction did not matter much, as bureaucratic activities were carried out in Russian, and educational institutions were switching over to Russian. Nonetheless, the acceptance of Ukrainian as one of two official languages during the early phase of the existence of the self-proclaimed Donbas republics had a symbolic meaning.

It is possible that Ukrainian’s loss of the “state language” status was an attempt to exert additional pressure on the Kyiv government to realize the Minsk II agreement, especially after the election of Volodymyr Zelenskyy as president of Ukraine. It was a way to show the Ukrainian government that without the realization of the agreements that would give the Donbas republics and Moscow a decisive influence on Ukrainian politics, Kyiv could lose these regions once and for all.

In terms of the politics of history, the adoption of a new doctrine – “Russian Donbas (Russkiy Donbass)” – was an important indication of the ongoing shifts. The doctrine was presented during an “integrational forum” that took place on 28-29 January 2021 in Donetsk with the participation of DNR and LNR leadership and representatives of the Russian State Duma. The document stipulated that the separatist republics were “Russian (russkiy) nation-states”, and that their future was within the “Russian world (Russkiy Mir)” and with Russia. As such, the doctrine had a more explicit Russian national character. At the same time, the narrative of the specific, multi-ethnic character of Donbas persisted, intertwined with a more explicit Russian national emphasis. The doctrine noted that,

Donbas is a special region of Eastern Europe and Eurasia, historically formed in the nineteenth century, which has its own economic and cultural characteristics, due to its autonomous position, which contributes to the creation of the Donetsk and Luhansk People's Republics.

Moreover, the document refers to the Russian language as the “framework, the fundamental basis of the unity of Donbas” and “of the more than 130 ethnic groups living on its territory”.

The merger between a more prominent Russian nationalist discourse, highlighted by the doctrine, and the narrative of a historically multi-ethnic Donbas was, among others, possible due to the ambiguities and polysemy of the word “Russian” (here, in the sense of russkiy). The word russkiy has several meanings in the political discourse.[10] In the narrow sense, it refers only to ethnic Russians. In another version, it can encompass Eastern Slavs – that is Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians – but exclude ethnic non-Russians in the Russian Federation. Furthermore, it can also have a broader civilizational or cultural meaning, encompassing people of different ethnic origins and cultures, who share certain common values, an appreciation for the Russian culture and language, and a certain understanding of history. The latter meaning (but also the second one) allows for a rhetorical expansion – both in the present and/or in historical narratives – of a Russian sphere beyond the borders of Russia proper.

The doctrine “Russian Donbas” seems to be playing with and instrumentalizing these different meanings of the word “Russian”. It allows its authors to simultaneously address and appeal to different audiences in the Donbas separatist republics, Ukraine, Russia and beyond: Russian nationalists, the heterogeneous Russian-speaking population in Donbas and other parts of Ukraine, and further afield. A close examination may reveal contradictions between the messages and narratives incorporated into the doctrine; although the coherence of historical narratives is a desired feature of any politics of history, it if not always necessary. The benefits of reaching out to and incorporating larger audiences sometimes outweighs the grievances of the few that feel alienated by an ambiguous and somewhat contradictory message.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 – encouraged, in part, by historical references and claims as well as a declaration of support for the separatist republics – also resulted, unsurprisingly, in fundamental changes to the breakaway polities. Importantly, the politics of history in the Donbas separatist republics always referred to territories larger than those controlled by the secessionist authorities. Their ambitions were not limited to controlling the entirety of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions – that was the minimum. The historical borders referred to in separatist discourses were much more ambitious. The inclusive nature of separatist historical discourses appears even more tragically ironic today, after all the destruction and suffering brought upon Ukraine by Russia’s invasion. The Donbas leadership’s politics of history have shifted from the legitimization of separatism towards the justification of the war effort and a direct “unification” with Russia.

Alexandr Voronovici: Separatism and the Uses of the Past: Politics of History in the Self-Proclaimed Republics of Donbas. Cultures of History Forum (12.08.2023), DOI: 10.25626/0147.

Copyright (c) 2023 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editor.

Viktoriia Nechyporuk · 13.12.2024

A Trident on the Shield: Ukraine’s Decommunization Strategy and the Case of the “Mother Ukraine” Sta...

Read more

Jeremy Cohen · 25.01.2023

Vladimir versus Volodymyr: Conflicting Russian and Ukrainian Application of Rus’ Heritage

Read more

Laura Eckl and Jan C. Bever · 31.08.2020

Ambivalent Memories: Commemorating 8 and 9 May in Kharkiv, Ukraine

Read more

Andrii Nekoliak · 16.01.2020

Towards Liberal Memory Politics? Discussing Recent Changes at Ukraine’s Memory Institute

Read more

Alexandr Voronovici · 07.08.2018

At the Crossroads of "Memory Wars": Recent Debates on the Babi Yar Holocaust Memorial Center

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).