25. Jan 2023 - DOI 10.25626/0144

Jeremy Cohen studies at the Center for Russian Eurasian, and East European Studies at Georgetown University’s Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service. His research interests include the role of history in international politics and the status of ethnic and religious minorities in Eurasian societies.

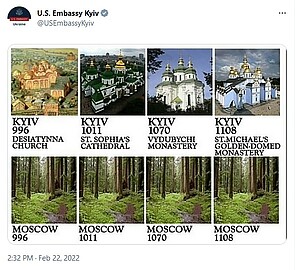

On 21 February 2022, three days before the Russian invasion of Ukraine began, Russian President Vladimir Putin made an incendiary speech in which he rejected the notion of Ukrainian statehood. In his history-laden diatribe, Putin questioned the idea that Ukraine has a national history distinct from Russia. The Russian president underscored how “since time immemorial, the people living in the south-west of what has historically been Russian land have called themselves Russian and Orthodox Christians.” He asserted how “we all know these facts” and that this information is “common knowledge,” yet these arguments were anything but broadly accepted, especially across the border in Ukraine. The claims Putin made to justify his impending invasion were an undeniable salvo in the war over Ukraine and Russia’s shared history. One response came from the U.S. Embassy in Ukraine, which retorted by posting a meme on its Twitter account depicting landmarks of Rus’ Kyiv contrasted with images of a primeval forest representing Moscow during the same period. The meme, which went viral and received support from Ukrainian users and official accounts, turned Putin’s narrative on its head by claiming that by predating Moscow, Kyiv, and by extension Ukraine, could not be considered a part of any historical sphere with Russia.

As Russia and Ukraine clash on the battlefield, they also wage a war over history of which the previous exchange is but one engagement. The history of Kievan (Kyivan) Rus’ is a critical front in that conflict.[1] Though the Russian and Ukrainian historical narratives of Rus’ is derived from the same medieval state, it has manifested in very different ways for each country. This article will examine how Russia and Ukraine have each manipulated and deployed the legacy of Kievan Rus’ in service of domestic and foreign policy objectives. While Putin’s Russia has deftly used the history of Kievan Rus’ to support a state narrative rooted in Orthodoxy and centralized power, Ukraine has primarily used its Rus’ heritage defensively with a focus on excluding Russia from the shared legacy. In both cases, the patrimony of Rus’ and the ability to shape the narrative on what the medieval state stood for and who has a rightful claim to its legacy today reveal a great deal about the priorities and strategies of the two states.

Before exploring the contemporary approaches that Russia and Ukraine use vis-à-vis their Rus’ legacy, it is important to recognize what Rus’ actually was behind the mythology that has cropped up around it. Kievan Rus’ was a collection of principalities that developed following the arrival of Scandinavian groups in the river networks of modern Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus, and their subsequent merging with local Slavic populations. Those Scandinavians, known in this context as Varangians and referred to by Donald Dixon as “warrior-merchants,” arrived in the mid-eighth century but exist today in a semi-mythologized state.[2] Though their arrival was immortalized in the Primary Chronicle (povest’ vremenykh let) with the story of the Call of the Varangians, in which the Slavs summoned “a prince who may rule over us and judge us according to the Law,” Dixon asserts that it is far more likely that the Slavs hired the Varangians first as mercenaries and that the leaders of those mercenary bands eventually claimed political control as the first princes.[3] Early Rus’ power was centered on Novgorod in the north and Kyiv in the south. The principalities thrived off their control of critical trading routes on the Dnieper, Volga, and Don rivers, and they played an important role in fostering commercial ties between northern Europe, the Middle East, and the Eurasian steppe.[4]

The watershed event in the Rus’ period came in 980 when Prince Vladimir (Volodymyr)[5] assembled the Rus’ principalities by defeating his brother Prince Iaropolk of Kyiv. With the Rus’ lands unified, Vladimir consolidated his power and took the consequential decision of converting to Christianity to legitimize his rule.[6] In 988 he married Anna, the sister of the Byzantine Emperor Basil, after capturing the Byzantine town of Chersonesus in Crimea and baptized himself there, followed by his people, in the Dnieper. The Christianization of Rus’ would follow Vladimir’s own conversion from paganism. For this, Prince Vladimir would later become Saint Vladimir.

Over subsequent generations the authority of the Prince of Kyiv as the centralized ruler of the Rus’ principalities declined. While Kyiv retained its significance as “mother of the Rus’ cities,” dynastic succession and political fragmentation eroded its position of primacy. The realm fractured and reverted into several feuding principalities, each owing nominal allegiance to Kyiv but ruled by its own Rurikid kniaz.[7] Ultimately, it was the Mongol invasion that would truly put an end to Kyiv’s political prominence. In 1240, Batu Khan conquered and sacked the city, leaving it a husk of its former glory, and causing the center of Rus’ power to permanently shift to the north and east.[8] The Rus’ period ended in many ways with the rise of Muscovy that resulted from the Mongol-induced power shift and the Muscovite victory over the Mongols at Kulikovo in 1380.[9]

As historian Serhii Plokhy contends in The Origins of the Slavic Nations: Premodern Identities in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus, Kievan Rus’ is the predecessor to Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus, yet even Kievan Rus’ did not possess a uniform culture, but rather different regional cultures. Moreover, he argues that none of those regional cultures can be directly traced to any of the modern Slavic nations.[10] In this sense, Kievan Rus’ is part of the shared patrimony of the East Slavic people as a whole, but it also existed in a very different cultural sense than the uniform one in which we typically conceptualize it.

Despite this, President Vladimir Putin of the Russian Federation has eagerly adopted Rus’ symbolism and imagery in order to mobilize support behind his vision for contemporary Russia. Two of the primary contexts in which this is evident are in his written and spoken statements on the one hand and in the government’s support for monuments invoking the Rus’ era on the other. As tensions with Ukraine increased following the Russian seizure of Crimea in 2014, the emphasis on the Rus’ legacy and its application in Russia’s contemporary narrative has increased.

Putin’s focus on Rus’ in his narrative of Russia’s twenty-first-century path is one that has predated the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. In July 2021, Putin penned an article published on the Kremlin’s website titled “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians.” While the article was a lengthy treatise that touched on over a millennium of Russian and Ukrainian history, he began by discussing what he characterized as a shared Rus’ history. He declared that “both Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians are the heirs of Ancient Rus’.” He also highlighted the dynastic and economic ties that connected the Rus’ states. In this narrative, he depicts Russians and Ukrainians as fraternal peoples, forever bound together by their common heritage. Tellingly, he also identified Saint Vladimir as prince of both Novgorod and Kiev/Kyiv, and cites the conversion of his realm as a marker of the unity of the modern Ukrainian and Russian people. By linking him to Novgorod, Putin underscores the grand prince’s ‘Russianness’. Putin’s emphasis on the baptism of Rus’ as being at the heart of Russian and Ukrainian closeness underscores a common theme in his rhetoric on the Rus’ legacy: the Orthodox Church. This idea supports his current ruling philosophy in which church and state are closely linked and serve as a critical element of the Russian national character, as well as provide a means of uniting Russia and Ukraine.

Putin makes the choice here to include Ukraine in his conception of Rus’ cultural and religious heritage. Rather than claiming exclusive right to the Rus’ heritage, Putin makes the strategic decision to include Ukraine under that same ancient umbrella as Russia, thereby strengthening his argument that the differences between the two peoples are minimal when put in the context of their shared history. In Putin’s philosophy, how could Russia and Ukraine be all that different today when they came from the same progenitor?

While the Rus’ heritage and appeals to historic unity between the two countries have been an important part of Russian framing, Russia’s style of narrative building around Kievan Rus’ has been equally focused on crafting a mnemonic narrative that plays to a domestic audience. In 2016, Putin unveiled a massive statue of Saint Vladimir near the Kremlin. The 16-meter statue was part of what an article in The Economist described as “a monument-building spree.” The bronze piece depicts Saint Vladimir standing upright, his right-hand holding a cross taller than himself and his left hand carefully clutching a sword at his belt. He gazes watchfully from metal eyes, adorned in a flowing robe and traditional Muscovite crown. In his speech at the unveiling, recorded by AFP and published on YouTube, Putin enumerated the two themes that the statue projects: orthodoxy and state power. He described Vladimir as “a visionary politician, who created a basis for a strong, unified, and centralized state” and called upon Russians to fight “modern challenges and threats by basing [themselves] on this spiritual legacy.” Here, Saint Vladimir’s legacy provides an effective pool for Putin to draw from to build a narrative of Russia as a religious, statist power. Regardless of the historicity of Putin’s claims, his version of Vladimir is one that reinforces state priorities and uses an imagined past to justify Russia’s current trajectory.

While the 2016 statue in Moscow is the most prominent monument to Prince Vladimir in recent years, it is far from the only monument that has been erected. In 2013, the Astrakhan local government erected a statue to the Kievan saint. In September 2017, a statue of Prince Vladimir was unveiled in Stavropol, which local news sites claimed was the first monument to the Saint in the region. The Stavropol statue was designed by the same sculptor as the colossus in Moscow, Salavat Shcherbakov, a Russian artist famed for his Soviet and later Russian nationalistic monuments.[11] Both the Stavropol and Astrakhan cases are particularly interesting because the cities lack any connection whatsoever to Kievan Rus’. Astrakhan, a former Tatar stronghold, and Stavropol, a city in the north Caucasus founded in 1777, were never within the influence of Rus’ and certainly bear no direct connection to the tenth-century prince. However, as President Putin continues to emphasize the importance of Prince Vladimir to Russia’s political and spiritual development, the medieval prince has ascended to a level of national significance in the Russian pantheon.

While Russia has deployed Prince Vladimir to buttress the government’s promotion of Orthodoxy and state power as central to Russian identity, it compliments this practice with reference to the historical figure of Prince Alexander Nevsky. While a significant religious figure in his own right, Nevsky offers a militaristic aspect to the current Rus’ mythology. Alexander Nevsky was a Rus’ prince who ruled during the thirteenth century as a tributary of the Mongol Golden Horde. He started as prince of Novgorod but later became Grand Prince of Kiev and the city of Vladimir as well. He is most famous for his victories at the Battle of the Neva against the Swedes in 1240 (hence his sobriquet) and the Battle on the Ice against the Teutonic Order two years later.

As a result of these victories, Russia has commonly used Nevsky as a model of patriotic defense of the motherland. In the most notable case surrounding his legacy, Joseph Stalin personally intervened to ensure that the blacklisted director Sergei Eisenstein was able to make his 1938 film Alexander Nevsky.[12] Russell Merritt describes Nevsky as a straightforward patriotic war movie, filmed with the overt goal of promoting anti-German sentiment in the tense environment of the 1930s. This is merely one example of the way that the Russian and Soviet states have built on the Nevsky legacy in service of nationalistic objectives.

Today, Putin and the Kremlin have promoted Nevsky’s image in light of the current war with Ukraine and the growing conflict with Europe and the West. In August 2022, Meduza, the Russian opposition news outlet now based in Riga, reported that Kremlin officials have directly “recommended” that media outlets write pieces comparing the “special operation” in Ukraine with the baptism of Rus’ and emphasizing the similarities between Vladimir Putin and Alexander Nevsky by showing the way that society united behind the leader in both cases.[13] In addition to promoting patriotic defense broadly, the case of Nevsky serves as a signal of opposition to real or imagined European encroachment. Just as Eisenstein deployed Nevsky to build patriotic sentiment against Hitler’s Germany by connecting it to the medieval Germanic Teutonic Order, the Kremlin’s use today has the clear undertone of defending Russia against European aggression meant to harm Russia. In 2021, Putin christened a new monument on the banks of Chudskoe Lake, the location of the Battle on the Ice. While historically significant, the site of the memorial on the border with Estonia is also telling of Putin’s anti-European sentiments. In this new monument, Nevsky and his companions are mounted and depicted riding out courageously to meet their enemy. They hold a massive chi-rho banner above them, affixed with an Orthodox cross on top. Nevsky himself stands at the center holding a cross, adding to the overtly religious message of the memorial. The lakeside hill also includes an older monument, built in 1993, that contrasts significantly with the newer one. Nevsky’s companions flank him, shoulder to shoulder with shields in hand. They stand emotionless in a defensive formation around their lord with their banners aloft, projecting resolve but not necessarily aggression. The two monuments tell very different stories, each consistent with the prevailing message and style of their time.

At the unveiling of the new monument, Putin hailed Nevsky as a defender of Russian territory who “showed everyone in the west and the east that the strength of Russia is not broken, and the Russian land has people who are ready to fight for it.” In this sense, Nevsky fits comfortably into the Kremlin historical narrative. The message bears major similarities to the Russian government’s focus on the Second World War in its emphasis of defense of the homeland and societal values.[14] At the same time, Nevsky is a malleable figure who can be used to affirm the Kremlin’s alliance with the Orthodox Church and the focus on centralized governance. In the cases of both Alexander Nevsky and Vladimir the Great, Russia strategically uses Rus’ history to construct a narrative that connects Vladimir Putin’s contemporary style of governance, and the challenges Russia faces, to the country’s primordial imagined past.

In contrast to Russia’s strategy of using the Rus’ past to bolster its domestic political structure and to pull Ukraine under its historical and cultural sphere, Ukraine’s strategy is largely focused on denying Russian claims to that heritage. In this way, Ukraine’s narrative is a defensive one, without a fully-fledged account of what the Rus’ history means for the country itself.

The clearest examples of Ukrainian official discourse on Rus’ history come from President Volodymyr Zelensky’s speeches. Even in 2021, Zelensky’s rhetoric on the Rus’ was clear: Ukraine is the successor of Rus’. In his speech honoring the Day of the Christianization of Kyivan Rus’-Ukraine, he stated, “There is a dash between [Kyivan Rus’ and Ukraine] in the text of the relevant decree of the President of Ukraine. And it is not just a punctuation mark. This is a sign that Ukraine is the successor of one of the most powerful states in medieval Europe.” A few things are notable in this short extract. First, Zelensky suggests that Ukraine is not merely a successor to Rus’, but the successor. His statement leaves no room for other claimants to the Rus’ legacy. He later elaborates on this by claiming that Ukraine is “rightfully” the heir of Kyivan Rus’ and adds that “cousins and very distant relatives should not encroach on her legacy. They should not try to prove their involvement in the history of thousands of years and thousands of events, being from the places where they took place thousands of kilometers away.” Here, Zelensky eschews subtlety in order to directly deny Russia’s claim to the legacy of Rus’. For this Ukrainian narrative, the claim to Rus’ history derives primarily from continuity and territoriality.

The second notable thing here is Zelensky’s use of geography. He situates Kyivan Rus’ as a “powerful state in medieval Europe.” Though an anachronistic claim, it is a seed of the Ukrainian narrative focused on Ukraine as a European state. By placing Ukraine within the historic bounds of Europe, Zelensky telegraphs Ukraine’s current intentions both to his own people and the international community. Though this style of strategic messaging around history seems less developed than in Russia, it is an important step towards making sense of Ukraine’s Rus’ history in the context of its current ambitions. This same sentiment can be seen in contemporary wartime Ukrainian media. In one example, the Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs shared a video on its Twitter account which claimed that “when Moscow didn’t exist yet, [Prince Volodymyr of Kyiv] converted to Christianity and decided we needed to join the European Union.” While clearly this statement was not meant literally, it underscores the developing Ukrainian narrative of medieval history that reinforces current objectives.

Zelensky’s wartime addresses echo his pre-war insistence of an exclusive Ukrainian right to the Rus’ legacy. On 28 July 2022, Zelensky delivered an address in honor of Ukrainian Statehood Day in which he emphasized the enduring resolve of the Ukrainian people in the face of the ongoing Russian invasion. In honor of the first year in which the holiday was observed, Zelensky stated, “the history of [Ukraine’s] state formation dates back thousands of years. But only this year we celebrate the Day of Ukrainian Statehood for the first time.” In saying this, the president suggests that Ukraine is not merely the successor of Rus’ but a modern incarnation of the same state. In addition to rejecting Ukraine’s historic subjugation by surrounding powers, he states without reservation that Ukraine “is the only legal heiress of Kyivan Rus’, the possessions and achievements of our rulers.” In making these claims, Zelensky seeks to defend Ukrainian statehood while simultaneously delegitimizing Russia’s own founding myths. By implicitly, but not subtly, labeling Russia as an imposter, he strikes at the core of Putin’s arguments that the Ukrainian and Russian people are essentially the same. After all, how could they be the same if they are not even descended from a common ancestor?

In an April 2022 speech looking back on the first fifty days of the war, Zelensky takes this rhetoric even one step further. When reflecting on the Russian attack on Chernihiv, he invoked the city’s medieval history to emphasize the brutality of Russian actions:

Ancient Chernihiv. Which is over a thousand years old. Which saw so many wars and so many invaders that at least in the XXI century it deserved peace and tranquility. But... Russia came. Came with the worst that Chernihiv has experienced since the X century. Since the period of Rus’ relation to which Russia once claimed. Now this myth is also burned. Rus’ would not destroy itself. Strangers did that to it. Horde and other invaders. That's who came to our land today. And they are fighting in the same way - for the sake of looting and for the sake of torture.

In this address, Zelensky declares that not only is Russia an illegitimate claimant to the Rus’ legacy, but it also represents a threat as grave as the Mongol Horde that sacked Kyiv and threatened all of Europe. In doing so, he uses Rus’ history both as a shield to protect Ukraine’s claim to statehood, but also as a cudgel with which to beat Russia. By likening Russia to the Mongols, Zelensky pulls from the reservoir of Rus’ history to contextualize Ukraine’s current struggle, while simultaneously rejecting any Russian claim to that same myth.

This approach encapsulates Zelensky and Ukraine’s zero-sum approach to the history of Rus’ today. While they do mention historic figures like Prince Volodymyr and Yaroslav the Wise and pay homage to the ancient Rus’ churches, the narrative focuses primarily on establishing an exclusive claim to that history and using it to build upon Ukraine’s fundamental right to statehood. Though there are emerging strategic threads, such as the emphasis on Ukraine as a European state, they are not yet fully developed.

Despite their shared ancestry by way of Kievan Rus’, Russia and Ukraine have employed differing strategies to craft that history into a national narrative. Russia’s strategy has largely focused on utilizing Rus’ heroes such as Prince Vladimir the Great and Alexander Nevsky to reinforce a national identity predicated on centralized government and Orthodoxy. At the same time, Ukraine has primarily sought to exclude Russia from the Rus’ narrative, thereby strengthening Ukraine’s own national identity by setting it apart. As the two countries’ paths continue to diverge at an accelerating rate as a result of the ongoing war, those historical myths are likely to become more developed and contrasting. In Moscow and Kyiv, two starkly different imaginary versions of Rus’ exist, both detached from the historical reality; one a traditionalist, conservative bastion, the other a member of the medieval European community. In both Russia and Ukraine, history is not an end unto itself but a weapon to be wielded in the domestic and international arenas. As the combatants pick their facts and craft their stories, it is evident that Rus’ can be whatever national priorities require it to be.

Jeremy Cohen: Vladimir versus Volodymyr: Conflicting Russian and Ukrainian Application of Rus’ Heritage, Cultures of History Forum (25.01.2023), DOI: 10.25626/0144.

Copyright (c) 2023 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editor.

Viktoriia Nechyporuk · 13.12.2024

A Trident on the Shield: Ukraine’s Decommunization Strategy and the Case of the “Mother Ukraine” Sta...

Read more

Alexandr Voronovici · 12.08.2023

Separatism and the Uses of the Past: Politics of History in the Self-Proclaimed Republics of Donbas

Read more

Violeta Davoliūtė · 01.06.2022

The Pop-Cultural Lineage of Russia’s Anti-Fascist Discourse: Unravelling the Plot of Putins’s War on...

Read more

Gero Fedtke · 27.08.2021

'Bukhenval'dskii nabat': The Life and Transformation of a Peace-Song in Soviet and Post-Soviet Histo...

Read more

Mykola Makhortykh · 28.06.2021

#givemebackmy90s: Memories of the First Post-Soviet Decade in Russia on Instagram and TikTok

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).