16. May 2019 - DOI 10.25626/0098

Monika Vrzgulová is Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Ethnology and Social Anthropology, Slovak Academy of Sciences in Bratislava. She has been conducting Holocaust and memory research since the mid-1990s. From 2005 to 2017, she served as the Director of the Holocaust Documentation Center in Bratislava and from 2005 to 2013, she was member of the national delegation of IHRA (ITF) as a member of its Educational Working Group.

![Entrance to the Holocaust Museum Sered’Author: Christian Michelides [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)] Author: Christian Michelides [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]](/fileadmin/_processed_/4/5/csm_KZ_Sered_Holocaust-Museum_7_rzd_bbb6d8d5de.jpg)

On the occasion of International Holocaust Memorial Day, the Slovak government unveiled its first and only Holocaust museum in January 2016. The museum, located on the historical site of the former Nazi concentration and labour camp Sereď, is part of the Museum of Jewish Culture, which was founded under the auspices of the Slovak National Museum and the Slovak Ministry of Culture.

The road toward this opening was long. An initial vision for a museum and Holocaust education centre on the Sereď site was presented at a meeting of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (ITF/IHRA) in Vienna in 2008. Shortly thereafter, formal and informal discussions began among government representatives, the Slovak National Museum – Museum of Jewish Culture, the Federation of Jewish Communities in the Slovak Republic and the Israeli Embassy in Bratislava about the nature of a future Holocaust museum in Sereď. Because the former camp site is located within a broader complex of buildings belonging to the Ministry of Defence, negotiations about exhibition space also involved that Ministry. In 2009, it was decided that certain barracks from the previous concentration and labour camp in Sereď would be transferred to the Slovak National Museum as part of the Museum of Jewish Culture.

While there may have been plausible practical reason for this institutional arrangement, it still comes across as misguided. The Museum of Jewish Culture’s primary focus is on presenting the century-old history of Jewish culture and heritage in Slovakia. By directly linking the Museum of Jewish Culture and the Holocaust Museum in Sereď, the Holocaust is presented as part of Jewish culture – a rather problematic message to send to the public.

The opening of the Sered’ Holocaust Museum at an authentic site constituted an important step toward creating historical awareness and a Holocaust remembrance policy in Slovakia. This part of the country’s recent history had entered public and political discourse as well as the educational sphere only relatively recently – after the fall of Communism in November 1989. In the 1990s, two rather different ways of viewing the recent history emerged almost simultaneously. Each became bound to a different ideological premise. The first school of thought, reflected in academic as well as public discourse, critically analyses and interprets the historical context and processes which had led to the creation of the independent Slovak State in March 1939, its totalitarian political system, legislation, domestic as well as foreign policy, etc. This school of thought also reflects on the Holocaust in Slovakia, including the responsibility of the then leading political representatives for this tragedy. The second school of thought is carried by a very diverse group. Its representatives usually call for ‘a plurality of views’ and diverse interpretations of the historical era. Yet its proponents are being criticized for aiming to merely proliferate their own beliefs or agenda. They predominantly focus on pointing out the significance of the existence of the first independent Slovak State (1939-1945) for the modern history of Slovaks. In their work, statehood is clearly ascribed more importance than the nature of the regime, which ruled the Slovak State at the time. They thus seem to downplay the fact that this regime was totalitarian and that it took active part in the genocide of the Jews in Slovakia. While research and academic debate about the period has proliferated over the past two decades, public debate about Slovakia’s Holocaust history remains ambiguous to this day. All the more significant is the state's interest in supporting the Holocaust Museum in Sered, the only one of its kind in the country and its exhibition can be expected to yield considerable influence on public historical debates and education.

The Sereď labour and concentration camp operated under the wartime Slovak state administration from September 1941 to March 1945, with a short break after the outbreak of the Slovak National Uprising against German occupation that lasted from late August to September 1944. The camp was established in the existing buildings of a former Military Engineering Unit’s Headquarters in Sereď.[1] The Sereď camp, as well as two other labour camps in Slovakia (in Nováky and Vyhne), were designated for the growing number of socially excluded and pauperized Jews from Slovakia, who had been stripped of their civil rights and their property through a government decree in 1939. The only Jewish organization which was officially permitted to represent Jews in the wartime Slovak State was the Jewish Council (Ústredňa Židov, ÚŽ). It was obligated to collaborate with the Ministry of the Interior on the organization of Jewish labour camps and centres. Officials of the ÚŽ tried to utilize the labour of the "dislocated” or "evacuated" and pauperized Jews within the newly established camps, so that they might ensure their own livelihoods and would not be a burden on the state budget.[2] Officials of the Ministry of Interior and other representatives of the regime were only interested in the continuing self-sufficiency of the Jewish labour camps, the turnover of finished goods, and the level of production. In order to keep up with production quotas, the Central Office for Jewish Labour Camps (Ustredna kancelaria pre pracovnetabory Židov) was established at the ÚŽ in order to help camps secure orders from various customers. In addition, the Jewish Council bribed camp commanders and guards in order to ease the life of the inmates.[3]

The Sereď camp was an outgrowth of existing temporary forced labour units which were created after 1939, in what was then the territory of Slovakia, in order to inter not only Jews, but also Roma individuals, and Slovaks who were deemed politically unreliable. Under the wartime Slovak state, concentration camps were an integral component of the “final solution” to the “Jewish question” in Slovakia. The totalitarian Ludak regime dominated by the Hlinka Slovak People’s Party (Hlinkova slovenská ľudová strana, HSĽS) established labour centres and then labour camps, including the one in Sereď, as part of a wider plan for the persecution and exploitation of Jewish citizens. The Sereď camp commander was a “deserving” member of the Hlinka Guard, a paramilitary organization of the HSĽS which guarded the camp during this time. The Jewish Police and the Jewish Board also participated in the camp’s administration. On the one hand, the Sereď camp functioned as an economic unit where labour represented partial protection and an opportunity to avoiding deportation; on the other, it served as a temporary detention centre for Jews, who were deported from there to other concentration camps outside Slovakia. Between March and October 1942 alone, at least 4 463 persons were deported from Sereď.

After the National Uprising against the German occupation in 1944, the Sereď camp was re-opened under the command of SS-Hauptsturmführer Alois Brunner, a close associate of Adolf Eichmann’s, who had previously organized the deportations of Greek and French Jews to Nazi concentration and extermination camps. His aim was to achieve the so-called “Final Solution to the Jewish question” in Slovakia; during this period, leading representatives of the Jewish Council (Ústredňa židov), such as Gisi Fleischman and Rabbi Armin Frieder, were imprisoned there. Academic research has also discovered, however, that inmates also included captured partisans and members of the resistance.[4 Under Brunner’s leadership, conditions within the camp became significantly worse: Jewish as well as non-Jewish inmates were tortured and murdered, or deported to other Nazi camps located in Third Reich-controlled territory.[5] From September 1944 to March 1945, eleven transports from the Sereď concentration camp and several transports from Prešov carried the remaining Jewish prisoners out of Slovakia. Some were sent to Auschwitz; others to Sachsenhausen, Ravensbruck, or Terezin. Approximately 13 500 people were deported.[6]

The final transport left Sereď camp on 31 March 1945 – a single day before the arrival of the Red Army in the town of Sereď.

Travelling down highway D1 from Bratislava, regularly placed signs direct drivers to the edge of Sereď, an easy 45-minute trip away. Here, however, the signs disappear and the entrance to the museum is hard to find.The author of this review visited the museum as part of group of Holocaust and gender studies scholars during an international conference in January 2019. We took a guided tour through the permanent exhibition, which turned out to be rather essential for understanding what was displayed.

The museum exhibition stretches over four of the original twelve barracks that made up the Sereď camp in 1941. In the three barracks dedicated to the permanent exhibition, three major themes are covered: the first barrack is dedicated to antisemitism in Slovakia from 1938 to 1945; in the second barrack, visitors learn about the camp's history; the third building is devoted to the concentration camps to which Slovak Jews were deported and to the Righteous Among the Nations (i.e. rescuers) from Slovakia.

Our visit began in the fourth building, in which the Educational Centre and temporary exhibition spaces are located. Our visit began with a viewing of two documentaries that presented testimonies of former camp prisoners, although we were not provided with guidance on how to use them for educational purposes or how they are used with non-expert groups visiting the museum. At first glance, the designers of the museum's permanent exhibition clearly wanted to create a strong visual experience for visitors: The entire space is dominated by posters, photographs and objects with minimal text present. As a result, the narrative of this place – its history and its role in the overall story of the Holocaust in Slovakia (and in Europe) – remains obscured. In fact, without a guided tour, the interpretation of the various images and objects on display is largely left to the visitor’s own expertise and prior historical knowledge. Three years after its opening, certain artefacts are still missing captions. While the necessity of a guided tour can be part of an overall exhibition concept, it is not the case here: Guided tours are optional, even though they are clearly needed for this particular exhibition. Moreover, there are no audio guides or even an exhibition catalogue available in Slovak or any other language, both of which could have provided missing context. But the museum offers the guided tour for organized groups (e.g. students).

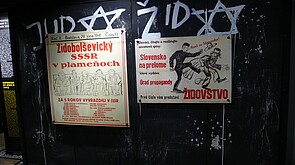

The first barrack is replete with reproductions of antisemitic posters and copies of regulations that were issued, for the most part, by the Propaganda Office of the Slovak wartime state. The atmosphere of the period is depicted through enlarged black and white photos of antisemitic signs hung on the walls of houses, copies of caricatures and images of Jews being intimidated and humiliated by the Hlinka guards. The images lack commentary or an explanation, leaving many questions unanswered. Why was state-sponsored antisemitism so successful after 1938 in Slovakia for example? What were the roots of political antisemitism in Slovakia and how was it expressed before 1938?

Visitors’ attention is drawn to large-scale glass walls marked with a list of names, but no information is provided about the people themselves. A knowledgeable person would likely suspect that the lists are based on the deportation lists of Jews from Sereď. But this is not explained and visitors do not learn about who prepared the lists or where the people whose names appear on these walls came from.

A brief text about the 1942 deportations from Slovakia provides a rather simplistic narrative of a complex issue. The same can be said about the information pertaining to the Holocaust in southern Slovakia, which was part of Hungary at the time. What happened during the Holocaust in these parts of Slovakia still awaits serious academic research. Why the curators chose to so prominently address the issue of deportations in the first barrack, otherwise dedicated to political antisemitism in Slovakia during the interwar era, remains a puzzle.

In the second barrack, the exhibition is dedicated to the actual camp itself, relying on visual representations in the form of historical photographs and a model of the camp's exterior and interior. There are also replicas with artefacts of the interior of the prisoners´ accommodations and the camp workshops. Commentary remains lacking, making it unclear whether certain artefacts are originals or merely replicas. Certain photos in this exhibition are captioned, "Photographs from official materials – reports from the Jewish Centre." By "Jewish Centre," the curators likely mean the Jewish Council (Ústredňa židov, ÚŽ), although this is only an assumption. Furthermore, even if visitors are told that the “Jewish Centre” created the photo documentation, this rather non-descript caption elides the fact that the Council was forced to cooperate with the Ludak regime to design and plan the construction and operation of the camp. By attempting to prove the ‘usefulness’ of the Jews in the camp to the state, the ÚŽ tried to save as many inmates as possible from deportation.[7]

The ambiguous role of the ÚŽ within the camp structure remains unclear to a less historically informed visitor. What does become visible is that the photos were originally created to demonstrate the economic value of the Jewish labour camp: Photos of smiling workers in clean, swept camp spaces and workshops give an impression of normality in a place focused on economic productivity. Here, yet again, texts explaining the purpose and aim of the photographs are missing. As a result, museum visitors run the risk of being misled about the realities of forced labour and the prisoners´ actual living and working conditions.

The history of the camp is presented in two short texts about the "First" and "Second Sereď," – labels derived from former prisoners' recollections. The use of emic labelling –categorizations made by eye witnesses – can be misleading in that it decontextualizes the history of this place, by only reflecting what a particular witness experienced, as opposed to building an understanding of the place as a whole. Visitors should be made aware that witness interpretation is subjective and only reflects on a retrospective evaluation of someone's direct experience. It is vital for a museum exposition to add historical commentary to individual testimonies in order to offer a more complex and accurate picture.

In those places where historical context is provided in the exhibition, it remains highly simplistic. This is all the more upsetting, as much research has been done and information made available about the camp’s different historical phases, as well as about the fundamentally different living conditions in the labour camp, compared to the parts of camp used to organize the deportation wave of 1942. To capture the multi-dimensional nature of the Sereď camp for Jews interned there in remains a crucial challenge.

During the "First Sereď" (following the term used in the exhibition) from September 1942 until August 1944, the living conditions of camp inmates, for example, varied considerably, something which is described in detail in many archival documents and survivor testimonies – none of which appear in this exhibition.

Moreover, during the first wave of deportations from Slovakia (March - October 1942), two separate camp-worlds co-existed side by side: in one, people worked and hoped that their hard labour would save them from deportation. In the other – the concentration centre – people were only “passing through,” awaiting certain deportation and likely death. The situation was further complicated by the fact that prisoners from the labour camp could be transferred at any time onto the transports from the Sereď camp.

Created to prepare for the 1942 deportations, concentration centres were situated near railways connected to existing infrastructure in Bratislava-Patrónka, Žilina and Poprad. The existing camps in Sereď and Nováky were also partly transformed into such centres.[8]

The last transport in 1942 departed from the Sereď camp on 21 September. From the spring of 1943, the official name of the camp became "Labour Camp for Jews."[9] Compared to the year before, the lives of camp prisoners became calmer and less stressful. The Hlinka guard members were replaced by a gendarme who served as the warden and who generally behaved in a less aggressive fashion.

The museum describes the period from September 1944 until March 1945 as "Second Sereď", indicating that during this period, the so-called Jewish question in Slovakia was definitively resolved, and, compared with the previous "First Sereď," conditions in the camp were cruel and inhumane. These facts are indisputable: The camp was overcrowded and the behaviour of the German SS was cruel. It would however have been important to inform visitors that the new camp commander, Alois Brunner, also restored production in some of the camp workshops (carpentry, radio repairs among others).[10] This information is missing, as are details about non-Jewish prisoners during this period.

In the third building, the exhibition provides information about the Nazi concentration and extermination camps which became the destinations for transports from Slovakia. Short texts briefly characterize the conditions in those camps and the victims' chances for survival. A collage of pre-war photos offers a glimpse of the Jewish community life in Slovakia destroyed in the Holocaust. The closing section of the exhibition is dedicated to rescuers, people who were awarded the title of Righteous Among the Nations for having helped protect Jewish Slovaks. The claim that a high per capita percentage of rescuers were active has existed in public discourse since the establishment of the Slovak Republic in January 1993. While it is appropriate to honour the humanity and courage of those who helped persecuted Jews in such dangerous times, it is also necessary to discuss this issue within the broader context of Jewish-Gentile relations during the Holocaust in Slovakia, as well as within the context of current remembrance policies regarding the wartime Slovak State. For the most part, rescuers began to help during the darkest period of Nazi occupation. By that point, nearly 65 per cent of the Jewish inhabitants of the wartime Slovak State had already been deported.

As currently conceived, the permanent exhibition conveys the story of Jewish victims and partially that of rescuers. Questions related to the regime and to perpetrators are also sketched out. However, there is no mention of the fact that the camp was situated at the edge of the town of Sereď and that the local population knew what was happening there, although current oral history research attests to the fact that the Sereď camp was part of the social memory of the inhabitants. The testimonies and other information gained through oral history projects with contemporary witnesses would have been useful in the development of the exposition.[11] The exhibition also neglects the challenging issue of the complicated role of the Jewish Council both within the camp and within the context of Slovak Holocaust history.

A Holocaust museum situated at a historically authentic site is an unique space which draws the attention not only of academics, but also that of educators working with younger generations. An important aspect of such a museum is its direct connection to the historical processes that today we refer to as the Holocaust or the Shoah, allowing for the study of archival documents and witness testimonies in their original buildings and surroundings. The challenge is how to tell its unique story with historical accuracy in an interesting, sensitive and emotionally compelling way.

The current permanent exhibition does not sufficiently provide this historical and contextual information, neglecting to sufficiently integrate a narrative that presents the history of this site within the framework of Slovak Holocaust history and within the context of Slovak contemporary remembrance policy.

At a time when voices that trivialize or cast doubt on the Holocaust in Slovakia, or that exculpate or diminish the responsibility of the Slovak state and its representatives and inhabitants for what happened to Slovakian Jews are growing louder, it is not enough to offer a visually interesting exhibition and a guided tour. An exhibition without adequate information and a clear narrative can easily be misused – not only to trivialize or question the significance of an authentic site, but also the Holocaust itself.

The creation of a comprehensible and interesting Holocaust museum exhibition is always a tremendous challenge. How do we communicate to our contemporaries, who live mostly peaceful and secure lives, how prejudices and discrimination can lead to genocide? How do we do so eloquently, while still respecting and conveying the complexities and ambiguities of history? What methods, tools and approaches should we use to capture the attention of the audience and provide accurate information? It is necessary to integrate both historical facts and memories, but visitors need to receive clear information so as to understand what happened and how to engage with archival sources and testimonies. Many similar Holocaust museums – both directly connected to the tragedy and in neutral locations – have successfully solved this challenge. Perhaps they could serve as an inspiration for this Holocaust museum – the only one of its kind in Slovakia. Much inspiration is available, for example, on the website of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, an organization the Slovak Republic joined in 2005.

The current exhibition at the Sereď Holocaust Museum can only be seen as the beginning of the journey towards a museum and memorial site that exhibits a comprehensive narrative that reflects the current state of research[12] and uses up-to-date museum didactical tools to convey the complicated history of the Sereď camp in the wider context of Holocaust history and remembrance.

Monika Vrzgulová: Only a Beginning: The Sered' Holocaust Museum in Slovakia. In: Cultures of History Forum (16.05.2019), DOI: 10.25626/0098

Copyright (c) 2019 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

![Author: Christian Michelides [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)] Sered' baracks, camp](/fileadmin/_processed_/5/b/csm_KZ_Sered_barracks__2017__01__rzd_4c9800b583.jpg)

![Author: Christian Michelides [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]](/fileadmin/_processed_/6/7/csm_KZ_Sered_Namen_der_Ermordeten_rzd_e9ac4519fd.jpg)

![Author: Christian Michelides [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]](/fileadmin/_processed_/d/0/csm_Sered_muzeum_holokaustu_10_rzd_115504717c.jpg)

See also the recent Interview with Andrea Petö about the Sered' Holocaust Museum (CEU podcast library, 04 March 2019)

James Krapfl and Andrew Kloiber · 28.05.2020

The Revolution Continues: Memories of 1989 and the Defence of Democracy in Germany, the Czech Republ...

Read more

Adam Hudek · 12.04.2015

The Unlucky Seven. Too Many Controversies Around the Celebration of the Seventieth Anniversary of th...

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).