05. Jul 2018 - DOI 10.25626/0086

Kara Brown is Associate Professor at University of South Carolina (USA) and an educational anthropologist whose research focuses broadly on the equitable transformation of public schools with particular attention to language and immigration policies. With established research lines in Estonia and the U.S. Southeast, Dr. Brown’s current projects in the field of comparative and international education explore the central role of teachers in creating and sustaining innovative linguistic and critical learning environments. With the support of a Spencer Foundation grant, she is currently (2018) living in Estonia researching the adoption of the first dual-language (Estonian-Russian) pre-primary programs across the country.

The Estonian National Museum – affectionately known as the ERM, for Eesti Rahva Museum – is newly housed in (probably) Europe’s youngest state museum building, and it has a (national) story to tell. But what kind of story, and how is it told? Its deliberate use of space – from the historical significance of its site and its architectural design to the presentation of displays in the permanent exhibits – projects an Estonian identity and serves the larger project of contemporary cultural production of the nation. Permanent space is allocated both to the Estonia-focused exhibit, “Encounters,” which ranges from early Estonian settlements in the Stone Age to the digital age, and to a Finno-Ugric exhibit “Echo of the Urals.” The ERM situates the Estonians amongst their Finno-Ugric brethren, in a manner distinct from the other major museums in Estonia, Tallinn’s Estonian History Museum and the Museum of Occupations.

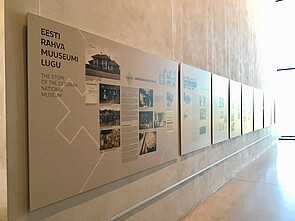

The first notable aspect of the Estonian National Museum, and its new building, is their very existence, which is not to be taken for granted, given the turbulent political history of Estonia. The museum itself was founded as a private initiative in 1909, nine years before Estonia’s declaration of independence in February 1918. The ethnographic collections that form the backbone of the museum began to be assembled in the nineteenth century when the Estonian territory was still part of the Russian Empire. As a spirit of national romanticism spread across the western borderlands of the Empire, Estonian folklorists like Jakob Hurt, whose bust gazes across the main entry of the ERM, began to call for the collection of local, material culture. The enthusiastic embrace of these organized efforts to gather and preserve materials of significance, especially clothing and household items, speaks to an early appreciation of the local, to the development of a sense of what it meant to be Estonian, as well as to an impetus to preserve this culture in changing times. The first period of Estonian independence (1918-1940), provided an opportunity for the ERM to become a foundation (1931) and to gain some state support. During the first Soviet occupation of Estonia in 1940-41, the museum was nationalized, but continued to operate. Exhibitions continued during the Nazi occupation (1941-1944), until museum workers were compelled to evacuate the collection prior to the Soviet bombing of Tartu (and the museum building) in 1943. The subsequent decades of Soviet rule transformed the museum, which was renamed in 1952 into the Ethnography Museum.[1] The history of the museum, fascinating and relevant as it is, is easy to miss: a traditional panel display in a side hall explains that “[e]ven in its shrunken and ideologically repressed condition, the Estonian National Museum was too great to fit into the framework of a specialized museum.”[2] In 1987, four years before Estonia regained independence, the museum restored its original name, and in 2003 – the same year Estonians decided to join the European Union – it was announced that, for the first time in history, a building would be built expressly for the ERM.

The second notable aspect of the ERM is that the museum has come full circle in terms of its location. The first significant base for the ERM, starting in 1922, was in the former Raadi Manor House (Raadi mõis) in Tartu, Estonia’s second-largest city and its intellectual and cultural heart.[3] The luxurious manor house and its grounds became a Luftwaffe airplane repair and maintenance base during the Nazi occupation (1941-1944) and were largely destroyed during the Soviet bombing of 1943. After the War, the Soviets transformed the Raadi grounds into one of the largest airfields in the Warsaw Treaty Countries – a major development, which lead to Tartu being declared a closed city to foreigners.[4] Due to the military base and nearby nuclear warheads, the Soviets prohibited the local population from visiting Raadi, a once-beloved spot for strolls and museum visits in the interwar period. Losing its Raadi home, the ERM was forced to migrate to a new location in the city centre.

For decades, however, Raadi remained important for nationally-minded Estonians as the erstwhile home of the ERM. In March 1988, once glasnost had created the possibility of protest, Estonians marched to Raadi demanding that the ERM be re-established in its historic home. Remarkably, permission was granted in June 1988 for both the renovation of the salvageable structures at Raadi and a new construction. In 1998, four years after the final withdrawal of Russian troops from Estonia, and seven years after the re-establishment of independent Estonia, the Raadi territory was returned to the ERM. Once an international call to design a new museum at Raadi was announced, the connection of the ERM to this location came full circle, from its roots in the 1920s to the opening of its new building nearly a century later in 2016. Just as the expulsion of the ERM and the construction of the Soviet air base in Raadi symbolized the destruction of Estonian independence, its return marked both the institutional reunion of ERM and its home as well as the national restoration of freedom.

The Soviet legacy, however, was profound, if often invisible, both at the site and in the national narrative presented at the museum. Severe pollution from its decades as a military base and the state of Raadi Manor House ruins made it a complex space in which to imagine a new museum. According to the architects, the space needed reclaiming and healing: Lina Ghotmeh, for example, acknowledged that “the [ERM] museum was […] a physically present ‘ruin’ of a painful history. The new Museum should play an essential role in the regeneration of the area and to do so it had to start by dealing with this heavily charged and spatially unique place.”[5]

The ERM building is itself a striking statement about Estonian national identity. As one approaches the building, from any direction, it rises dramatically out of the ground. Aerially, as well as from the rear B entry, the lines of the building continue and extend the existing Soviet-era airstrip (though this symbolism and design can be wholly missed if one accesses the museum through the main A entry). According to Dorell. Ghotmeh. Tane Architects, the winning, international team who designed the new building, "The structure resembles a glass wedge inserted into the landscape that slowly reaches upward from the ground — a built allegory for the country’s emerging history."

The ERM is unlike any other public structure in Estonia in scale and design. The 34 000 m² structure holds 140 000 objects. Among public structures in Estonia, only the National Library (Eesti Rahvusraamatukogu) is larger (51 477 m2). The new building was expressly designed as a museum and spaces were tailor-made for their contents, a first for the ERM. The museum design is deliberately and inherently not representative of Estonian vernacular (or other national) architecture. Instead, the 355 m-long glass building, which cost 75 million euros, is decidedly looking to the future. Stretching over the lakes of Raadi, the building’s sheath is a nod to the national: it is wrapped in a pattern of white octagonal stars evocative of cornflowers, the Estonian national flower, and snowflakes.[6]

While the airstrip embedded into the design of the museum suggests taking off, the building as a whole can also be understood as an arrival; not only has the ERM finally arrived “home” to Raadi, but Estonians have arrived as well as an independent European state; they present themselves to the world - with, and through, this museum and building. The museum recognizes that it serves a global audience. All audio and text files in the “Encounters” permanent exhibit are accessible through an ingenious digital card system that allows visitors to switch the text on tablets and screens to one of seven languages: English, Estonian, Finnish, French, German, Russian, and Latvian. The “Echo of the Urals” permanent exhibit is available in English, Estonian, and Russian. The museum’s architects, who aimed to create in Estonia “a landmark cultural building that could sit beside those in other European nations,” have already successfullz in garnered international recognition.[7] The ERM, its architectural team, and/or the museum administrators were awarded the 2016 Grand Prix AFEX: for edifices built abroad by the French architects and the 2018 European Museum Forum’s Kenneth Hudson Award for the "most unusual and daring achievement that challenges common perceptions of the role of museums in society."

“Encounters” — the permanent exhibit on Estonian culture and national development showcases both the historic and ethnographic streams of the ERM. In this exhibit, historical knowledge is staged in episodic moments organized along the broad theme of “Journeys in Time,” including the "Time of Freedoms", "Life Behind the Iron Curtain", "Modern Times", "the Era of Books", "the Arrival Christianity", "the Metal Ages", and "Stone Age". These chronologically arranged exhibits run in a line down the main hall, or lower airstrip, of the ERM. It is possible to enter the exhibition hall either at the Stone Age, on one end (entry B), or at the current-day “Time of Freedoms” (entry A). That said, the primary entrance of the museum with its soaring main hall, bust of Jakob Hurt, extending over the ground’s small lakes, leads you directly into the “Time of Freedoms”-part of the exhibit. Channelling visitors into the present day is one of the few guiding junctures in this permanent exhibit; once inside, people choose their own path through and around the array of tall plastic display tubes, various-sized showcases, large concrete structures, and other objects that fill the three halls, and various rooms, and pockets along the wall. Within this open floor plan dotted periodically with larger digital screens pillars introducing the seven major temporal groupings, visitors create their own “journey”; there are neither directing arrows (to suggest a path through the exhibit as are present in the “Echo of the Urals” exhibit) nor a sequential master narrative to guide people along a set path. And, in the spirit of the title of this permanent exhibit, the open design creates a space where visitors may “encounter,” or conversely completely miss, different aspects of the Estonian story.

The only exhibit all visitors encounter when entering through the A-entrance is “Innovation is tomorrow’s everyday life.” In this constantly refreshed part of the exhibition, the curators introduce “the ways that scientists, engineers, technology developers, and artists create innovations in contemporary Estonia.” The 2018 iteration of this exhibit includes the sharing of digital artefacts ranging from a chair on which Jaan Tallinn invented Skype to an e-residency card. Juxtaposed with this display is a sacrificial stone where visitors learn that Estonia is the least religious country in Europe. This opening display begins to sketch the contours of Estonian identity as embedded in a future-focused, digitally defined, society.

In the introductory space of “Encounters,” visitors are also shown a news video clip of the first Estonian President Lennart Meri’s 1997 press conference in a Soviet-era bathroom at Tallinn’s airport. According to the display, Japanese businessmen had previously commented to the then President Meri about the ways the airport’s dilapidated Soviet-era toilets would “interfere significantly with Estonia’s foreign relations.”[8] In sharing this video clip in the prominent entry space of the permanent exhibit, a broader message is conveyed, both about the importance of making a pointed effort to break with the vestiges of Soviet and with the sensitivity to outsider perceptions of Estonia – a message that sets the tone for Estonia’s post-Soviet transformation.

Progressing from the “Time of Freedoms” into the “Life Behind the Iron Curtain” section, visitors begin to note the curators’ attention to both domestic and international visitors. One example of this dual-audience attentiveness can be found in the Baltic Chain video and photo montage, depicting the events of 23 August 1989, when two million people commemorated the fiftieth anniversary of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact by forming a human chain across the Baltic States from Tallinn to Vilnius. While the display outlines the origins, purpose, and interpretations of the event, an additional text poses a decidedly local (or Baltic-based) and participatory question: “Where did you stand?” followed bz the comment “If you have any photos or films at home, please share them with us.”

The Soviet occupation exhibit highlights the divide between the “capitalist West” and the Soviet Union, but also points to the distinctiveness of Estonian space within the USSR. According to the “Behind the Iron Curtain” display, “[c]ompared to the rest of the Soviet Union, Estonia became a different, westernized region, a so-called Sovetsky Zapad (Rus: Soviet West).” That said, the exhibits in this section speak of Estonians as part, or becoming part, of a Soviet collective. The “Soviet person,” who, as the “Do it yourself” display brilliantly depicts with a homemade lawnmower, “had to be inventive and skilful. [...] DIY was an intrinsic part of a Soviet person’s everyday life.” The display cases on the deportations, the introduction of collective farms, and mass Soviet culture in particular, capture the Soviets' strategies – from the role of fear to the used of propaganda – for transforming society. “A Countryside in Change” display inform visitors that “[b]etween 1947 and 1950, harsh taxes and fear of deportation made farmers join collective farms, where they had to work to fulfil orders and plans.” While the new, rural apartment blocks with running water were part of a “new lifestyle […] supposed to erase old memories and create a new identity.” Visitors are poignantly reminded in “Culture for the Masses!” that,

the greatest, and most unnoticed help in losing a truthful image of historic event and creating a new, Soviet mentality, came from the ‘right’ books, entertaining plays, films, and tv shows. This situation resembled today’s advertising campaigns, repeated day after day, which affects everyone to some extent. Thus, in the 1960s, Soviet thinking finally took root in Estonia.

Advancing through the “Journeys in Time” part of the permanent exhibit, documentaries, drama, news clips, historic photographs, digital maps, and various other media supplement descriptive texts to further develop aspects of Estonian identity. An emphasis throughout this section, and the “Encounters” exhibit as a whole, is on the experiences of common people, rather than a veneration of particular political or cultural leaders. An exception here is a textual display related to Lembitu “the ancient chieftan of Sakala County” who fought in the northern Crusades in the early thirteenth century. Attention to the lived experiences of everyday Estonians also features prominently in the “Parallel Worlds” exhibit located a couple of halls over from “Journeys.” In this section, curators introduce visitors to the “main characters” from 1939-1989 “who are born in Estonia and have lived here, who have left here and been taken from here, who have come here and who have stayed here”. In returning to the “Journeys” exhibit, visitors find further attention to the everyday; everyday events, like fairs or tavern life, are highlighted more than significant military or political turning points (with the exception of the ERM’s attention to the 1905 Revolution).

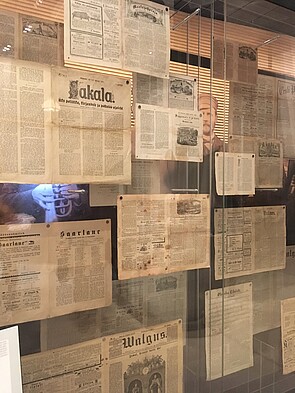

Three major displays running across several historic eras point to the importance of the Estonian language for Estonians. From the substantial Soviet-era bookshelf (“The Bookshelf of the Two Hanses”) containing a secret cupboard (salakapp) that stored forbidden Estonian-language literature from the first period of independence, to the showcase of the Estonian-language press during the nineteenth century era of Estonian national awakening, curators highlight the defining aspect of reading and writing in Estonian for building a sense of national identity. Theses exhibits are punctuated with an “Era of Books” showcase that traces the rise of literary culture in Estonia from the fifteenth through the nineteenth century through the display of a range of key religious and secular Estonian-language books (as well as interactive, digital copies of these books behind the case). The oldest surviving ABC book printed in the Northern Estonian dialect from 1694 is spotlighted in its own nearby cement case topped with a cockerel. This display projects the early importance of both the Estonian-language and formal education for Estonians.

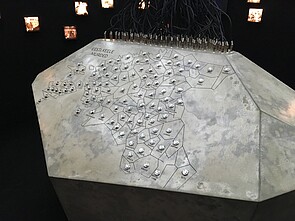

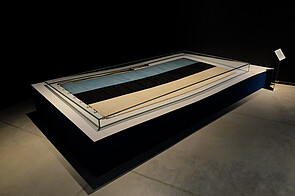

Parallel to the “Journeys in Time” are eleven thematic exhibits to the right and left of the “air strip”, displaying, for example, the Estonian blue-black-white flag in its own solemn room, an audio maps of runic songs, and a visual and musical exploration of Estonian blankets and rugs. The swirling linguistic diversity on display in the “Language Brew” room centres on a main station featuring dozens of Estonian dialects, a handful of major contact languages (e.g., Finnish, German, Russian, etc.) and Finno-Ugric languages. In this interactive exhibit, linked to selections from Estonia’s extensive oral archives, visitors can listen to any of the languages by pressing a button. While this display and the “Era of Books” touch on the history of parallel written languages of Northern and Southern Estonian in the nineteenth century and speaks to the centrality of the Estonian language for Estonian identity, the museum fails to mention the more recent history of language activism. For example, the “Estonian Dialects” side panel in the "Language Brew" room notes “[i]n the 1990s, however, Estonian dialects began to emerge. The Võro dialect, for example, has developed into a written language.” Excluded from this panel text is the government’s decision not to recognize Võro as a language, despite several attempts to advance to this status in the early 2000s. This omission is a missed opportunity for the museum to communicate one of the many dynamic contemporary attempts to reimagine and redefine Estonian identity in the twenty-first century.

The “Farm Life and Farm Beauty” section, as well as the “Imprint of Time on Estonian Blankets and Rugs,” display a selection of some of the oldest items in the ERM collection, explained through text and technology. Video displays about the preparation of linen and wool sit on wooden beams alongside some of the key material objects. Continuity of past and present identity is depicted in descriptive signs, like “Estonians have had a special relationship with woollen mittens and gloves.” In the Estonian blanket and rug room, a high-tech program allows visitors to create music based on selected traditional patterns. Collectively, these spaces speak to the rural roots of most Estonians and the once distinctive aspects of local and regional identities, as reflected in carefully identified clothing, blankets, and beer tankards. These sections also reflect the early, national-romantic roots of the ERM in which the museum collection, and the act of collecting, worked to define and create a sense of what it meant to be Estonian.

The “Encounters” exhibit, as a whole, continues to advance a bounded rather than a dynamic and shifting sense of Estonian identity in both ethnic and civic terms. While visitors hear a story of Russian integration in “The Life Behind the Iron Curtain” exhibit, a more discrete perspective on national identity is communicated throughout the remainder of the museum. The notion of an enduring, even timeless, Estonian identity and culture is perpetuated through displays about national minorities, where visitors learn that coastal Swedes “embellished” Estonian culture, to the Lembitu display where we learn of this twelfth-thirteenth century “Ancient Estonian,” to the Metal Age exhibit that mentions that, “the memory of ancient times persists in the genetic code of Estonians, and in their language, culture, and landscapes.”

Leaving the main Estonian exhibition (on the “current-day”-end of the basic timeline), and turning right, visitors find carved wooden doors leading to the second permanent exhibit “Echo of the Urals.” This smaller exhibition makes a statement not only about the longstanding importance of the Finno-Ugric connection for Estonian identity, but also about the collective responsibility of the ERM to serve as a museum space for those Finno-Ugric peoples without a state (i.e., excluding Finns, and Hungarians). The ERM has a well-established history of research in the Finno-Ugric areas; a sphere that was deepened during the Soviet occupation.[9] While the struggle for national survival is foregrounded in the “Journeys in Time” part of the “Encounters” exhibit, this historic and contemporary aspect of Finno-Ugric life is absent from the “Echo” exhibit. Visitors are left to imagine recent history and the current state of affairs for the “small” Finno-Ugric peoples as they attempt to preserve their cultures in current-day Russia (and beyond). Some of the introductory touchscreens in these rooms (next to the doorway) provide a glimpse into contemporary efforts (e.g., by Tornedalians and Kvens) to revitalise languages and gain legal recognition as minorities; these photo-linked descriptions help to bring the cultures of these Finno-Ugric peoples into the twenty-first century.

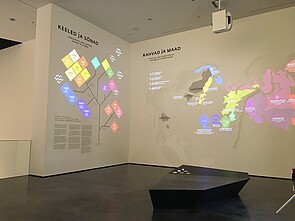

The first-floor entry hall to this exhibit introduces the Finno-Ugric world through language and geography. Linguistic connections, or distances, can be explored across six words – tree, fish, heart, nest, eye, and water – via the interactive audio Uralic Language Tree. An adjacent map displays the location and population size of the various Finno-Ugric peoples.[10] With reference to this map, an ERM text points out the meaningfulness of linguistic kinship for understanding links across people and cultures, since it "has inspired a number of scholars and artists to theorise about Finno-Ugric culture, and to note the similar ways of thinking, as well to search for common traits in both the material, and spiritual, cultures of the Finno-Ugric peoples."[11]

Further potential unity across these peoples is suggested through the highlighting of genetic similarities via touchscreen at the entry of the bottom floor of the exhibit. A museum guide explains the broad concept of “Finno-Ugric Ethnogenetics”, that the Finno-Ugric and Samoyed peoples

share about one third to half of their paternal lines with many Siberian peoples. This commonality covers the entire Arctic, from the Sami in the west to the Chukchi and the Koryak far in the east. In this regard, we [sic] clearly differ from western Europeans, such as the Swedes or French, as well as the Poles.[12]

The museum points to additional key aspects of this distinctive Finno-Ugric identity in three display cases at the entrance of the bottom level. Here visitors are introduced to key Finno-Ugric ideas, like “ethnofuturism,” a concept developed to capture ways of bringing indigenous communities into the future.

The Estonians’ technological prowess is on full display as they share the culture of their fellow Finno-Ugric people. The material culture in these exhibits, organized into four, distinct rooms based on regional Finno-Ugric groups transport visitors through a different season and time of day in each space: the Permic hall’s spring morning, the Volga Hall’s summer noon, the Baltic-Finnic hall’s autumn evening, and the Nordic Hall’s polar night. The display rooms are saturated with images, full of sounds, and infused with technology. For example, a blue river of light with motion-activated symbolic fish and gurgling sounds guides visitors through the lower-floor of the exhibit; 55” touchscreens allow visitors to examine objects more closely in all the rooms; and an elaborate, tailor-made soundscape (140 different channels are used) forms a natural backdrop to the display of material objects.[13]

The architects and curators of the Estonian National Museum have infused this institution with meaning; a concrete, material, expression of Estonian values and identity are projected through the museum’s location, its architecture, and the design and content of its exhibits. One final, important feature to note regarding this museum is that it also serves as a generative space for cultural showcasing and production. From hosting the Presidential reception for the centenary of Estonian Independence Day in February 2018 to using the Raadi grounds to host a public celebration of St. John’s Day in June 2018, the Estonian National Museum emerges as a broad space to preserve, present, and promote contemporary cultural expressions of - but perhaps not to reconsider - what it currently means to be Estonian.

While the ERM neither presents a master narrative about Estonian culture and history nor forces visitors to engage with certain key exhibits in “Encounters,” the curators, through their decisions about what to showcase and omit, define the core aspects of Estonian identity. As mentioned above, the Estonian language clearly plays a central role in defining the nation. In making these decisions, the ERM, as it is currently curated, misses an opportunity to explore the ways in which enduring Estonian traditions continue into the twenty-first century as a living culture. These traditions, be it having saunas, holding Song Festivals, embracing a range of musical traditions, enjoying handcrafts or taking in plays, just to name a few, get little to no attention in the museum. They have also taken new forms (as we see with many new versions of the song festivals including punk or regional-language versions) or enjoy renewed attention (e.g., smoke saunas in southeastern Estonia) which points to the dynamic aspects of Estonian culture. Finally, visitors get a glimpse of how Estonian identity has changed over time, but the museum largely does not address how this identity is changing or being reimagined in the present day as Estonians currently “encounter” religious, linguistic, ethnic, and racial “others” and as others learn Estonian. With one exhibit hall open to continually changing, publicly-proposed and crafted exhibits, perhaps this theme will be taken up in future years at the ERM.

Kara Brown: Layered Spaces of Meaning: The Estonian National Museum. In: Cultures of History Forum (07.07.2018), DOI:10.25626/0086.

Copyright (c) 2018 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

The official website of the Estonian National Museum (Eesti Rahvamuuseum)

Heiko Pääbo and Eva-Clarita Pettai · 27.03.2019

A Museum of Memories: The New ‘Vabamu’ in Tallinn

Read more

Lorraine Weekes · 25.04.2017

Debating Vabamu: Changing names and narratives at Estonia’s Museum of Occupations

Read more

Heiko Pääbo · 25.10.2015

"1944" vs. 9 May – An Attempt at Reconciliation Instead of Vigorous Glorification: Estonia Commemora...

Read more

Maria Mälksoo · 30.04.2014

Estonia - The Ukrainian Crisis as Reflected in the Estonian Media

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).