31. Jul 2020 - DOI 10.25626/0119

Katarina Ristić is a research associate at the Global and European Studies Institute (GESI) at Leipzig University. She is author of Imaginary Trials - War Crime Trials and Memory in Former Yugoslavia (2014). Her research focuses on issues of transitional justice, memory and media, most recently on transnational memory activism via online media and visual memory of the Yugoslav wars.

In the autumn of 2019, the Nobel Prize for Literature was awarded to the Austrian writer Peter Handke. The Nobel Committee’s decision sparked a harsh debate throughout the region and beyond, as Handke was well known not only for his literary work, but also for his support of Slobodan Milošević and the Serbian regime during the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s. He spoke publicly against the demonization of the Serbian side in the conflict, minimizing the war crimes committed by the Serbian forces. He visited Milošević in the International Criminal Tribunal for former Yugoslavia (ICTY) detention unit almost a decade after the end of the war, and attended his funeral in 2006.

The debate revolved around two main positions: one group denounced Handke as a ‘genocide apologist’ while the other praised him as the ‘conscience of humanity’, who recognized the marginalized truth of Serbia’s victimhood. The extreme positions in this debate neatly capture the continued divisions in retrospective interpretations of the Yugoslav wars. Based on the analysis of around 50 articles published in international and regional online media and on Twitter, this article will look into the Handke debate which began the very day the 2019 Nobel Prize for literature was announced on 10 October 2019. It continued till the award ceremony two months later, and included journalists, politicians, writers and academics, who argued either in favor of, or against the Nobel Committee’s decision. The analysis is structured in three main parts: the first will outline the different positions taken by authors from international media outlets who evaluated Handke’s literary merits against his past politics. Second, the article will look at the responses to the award in the region e.g. politicians proclaiming Handke a persona (non) grata and bottom-up initiatives against the Nobel Prize winner. Finally, I will discuss two different explanations for his political engagement: the intellectual skepticism put forward by Handke himself and the historical revisionism steaming from his vanity, as argued by his critics. I conclude that the Nobel Prize for Handke served as a catalyst to revive the memory war in the region and beyond, while the debate stands as a bitter reminder of the enduring conflict over the divergent memories of the 1990s wars.

Many of the comments and articles surrounding Handke and the Nobel Prize did not engage in any evaluation of his literary merits, but simply repeated the official press release by the Swedish Academy, saying that Handke was awarded “for an influential work that, with linguistic ingenuity, has explored the periphery and the specificity of human experience”. Some authors noted that Handke’s literary work had long deserved such a prize. Yet, with the exception of one article published in the English language by China Daily, all the articles in one way or another addressed the debate about Handke’s moral complicity as a denier of Serbian genocidal politics. For Chinese readers, the Nobel Prize seemed to be a logical and unquestionably well-deserved award for an obvious candidate.[1] Similarly, the self-evident literary value of Handke’s work was stressed by articles published in Russia Today, and in most of Serbian media. Reporting about the international reactions to the decision, Russia Today noted that Handke is “a playwright with unquestionable literary achievements”, while criticizing the moral standards of Handke’s critics. References to Handke’s literary merits were also made in a Reuters report, where the writer was described as one of “Europe's most influential post-war writers”. This evaluation was further supported with a statement by publisher Lojze Wieser who claimed Handke to be “the greatest innovator of language and word in global literature”.[2] Although both Russia Today and Reuters evaluated Handke’s moral position on the Yugoslav wars from opposite perspectives, neither seemed to question the value of his literary work.

However, the largest group of articles and commentaries in international media, argued that even though Handke’s writing might hold literary value, this was discredited by his public support of Milošević’s genocidal regime, which made him an unsuitable candidate for the prestigious Nobel Prize. In a much-quoted op-ed published by the New York Times, the writer Aleksandar Hemon called Handke “the Bob Dylan of genocide apologists”.[3] Hemon admitted that during his youth he liked Handke’s books and even considered him a role model as a writer, yet this changed with the war in Yugoslavia, when Handke started relativizing or minimizing the war crimes committed by the Serbian forces. And while Milošević and other Serbian politicians ended up arrested and indicted for war crimes, he lamented, “Mr. Handke’s support for the butcher of the Balkans went on unabated”. Although allowing for the possibility that postmodernist suspicions of representations and specific aesthetics might have contributed to Handke’s “immoral delusions”, Hemon concluded that “Mr. Handke’s politics irreversibly invalidated his aesthetics, his worship of Mr. Milošević invalidated his ethics”.

Ed Vulliamy, a well-known war journalist who reported about the camps in Bosnia and who has ever since fought for the recognition of Bosniak victims and the condemnation of the crimes committed by the Serbian forces during the war, wrote in a similar tone in the Guardian that awarding the Nobel Prize to Peter Handke dishonoured the victims of genocide. He added that “whatever his literary merits, the author’s dismal morals should have disqualified him”.[4] In August 1992, Vulliamy was part of a team of journalists who entered the Trnopolje and Omarska camps, where Bosnian Serbs imprisoned thousands of Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats during 1992, exposing them to molestation, torture, sexual crimes and murder. The texts and images that were released after the visit by Vulliamy and the ITN team marked the moment when the war in Bosnia – perceived by the Western media as a civil war between three parties – turned specifically into Serbian aggression and genocide.[5] Vulliamy testified about camps in several ICTY trials, including the trials against Duško Tadić and Radovan Karadžić.

Long-time German correspondent for South-East Europe, Michael Martens, accused Handke in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ) of repeating the main claims of Serbian nationalism, namely that the shelling of Sarajevo was not a military action by Bosnian Serbs, or that Serbs were the main victims of the Yugoslav wars.[6] In the French weekly L’Obs, Elisabeth Philippe maintained that Handke’s interpretation of the atrocities by the Serbian army as a reaction to provocations or justified by the memory of crimes committed in the past was nothing but historical revisionism, reminiscent of the ‘Blut und Boden’-ideology of Hitler’s Germany.[7] Similarly, Svetlana Slapšak, in the web portal Peščanik, published that the identification of the Serbian nation with Milošević’s world disqualified Handke both as a writer and as an intellectual: “This is not a question of ideas or political sympathy, but of a serious lack of observation, knowledge, sensibility, and impulse to love the oppressed and victims more than tyrants and abusers: in short, the literary capacities that are important to writers today and to their work.”[8]

Finally, criticism turned towards the Nobel Committee itself for selecting such an author for the most prestigious literary prize. Journalist Peter Maas, another war time journalist who reported about camps in Bosnia[9]titled his article in The Intercept: “Congratulations, Nobel Committee, You Just Gave the Literature Prize to a Genocide Apologist”.[10] In order to stand against relativization, he started a Twitter campaign under the hashtag #BosniaWarJournalists, inviting journalists who covered the war in Bosnia to describe what they witnessed during that time. Among the thousands of tweets and shares that followed, one could find many renowned journalists like Jeremy Bowen from the BBC, Christiane Amanpour from CNN, David Rohde from The Christian Science Monitor, Joel Brand from the Washington Post, all the way to the scholar and former US representative to the UN, Samantha Power. Amanpour for example posted: “I was there. We all know who is guilty”. These tweets received wide resonance, leading another prominent human rights activist from Bosnia, Refik Hodžić to tweet:

I am deeply touched by the solidarity of war correspondents who reported from Bosnia, sharing their stories to counter the vile denial promoted by the @NobelPrize by awarding Peter #Handke. Deeply touched and thankful to all posting on #BosniaWarJournalists #BosniaWarReporters.

For the majority of critics and war correspondents from Bosnia, the relativization of war crimes and revisionism disqualified Handke as an author, consequently invalidating his work and making him an unsuitable candidate for the prestigious Nobel literary prize. In the region the debate took a different turn: a number of political decisions were taken to signal appreciation or dismay with the Nobel Committee decision, while bottom-up initiatives centred on the victims and survivors and their dissatisfaction with the award.

Although the Handke debate raged for days in international media, it was primarily intellectuals, academics and journalists who took part in it. In the region, on the other hand, politicians were quick to engage in the debate, mostly via social media channels, doing what was in their power to punish or congratulate the new Nobel Prize winner.

Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and Kosovo decided that their ambassadors would not attend the Nobel Prize Award ceremony in Sweden. Kosovo Minister of Foreign Affairs, Behgjet Pacolli announced that the Kosovo Ambassador in Sweden would not attend the Nobel Prize ceremony, while Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina joined the boycott. This decision was ridiculed in the Serbian right-wing media outlet Kurir noting that the region “went mad because of Handke”.

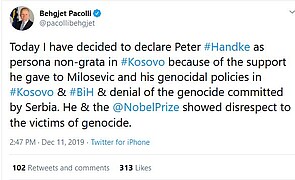

On the day of the ceremony, several protests were organized in Stockholm, where one group of protesters demanded that Handke apologize to victims, while another praised him for telling the truth about the war.[11] On the same day, Handke was declared a persona non grata in Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which endured a 43 month siege during the war which killed more than 10,000 people in shelling and sniper attacks. Kosovo’s former president and current Minister of Foreign Affairs, Behgjet Pacolli wrote on his Twitter account a day later:

Today I have decided to declare Peter #Handke a persona non-grata in #Kosovo because of the support he gave to Milošević and his genocidal policies in #Kosovo & #BiH & denial of the genocide committed by Serbia. He & the @NobelPrize showed disrespect to the victims of genocide.

Declaring Handke a persona non grata in Kosovo and Bosnia, predictably prompted Serbian politician Marko Đurić to reciprocate and declare Handke a “persona gratissima” praising his bravery for speaking truth to power. Handke had been made an honorary citizen of Belgrade already in 2015, and after the Nobel Prize was awarded in December 2019, it was suggested that one street in Belgrade should be named after him. In Serbia, the win for Handke indirectly symbolized the recognition of Serbian victimhood during the war, and Serbian president Aleksandar Vučić sent his congratulations to the “respected friend” adding that Serbia “felt as if the prize was won by some of us. Now, with Ivo Andrić, we celebrate one more Nobel Prize winner as ours”.

While Serbia was celebrating its own Nobel Prize winner and bookstores were filled with Handke's books, Albania’s Prime Minister Edi Rama tweeted that he wanted to “vomit” because of it; the president of Kosovo, Hashim Thaçi, demanded an apology from the Nobel Committee for the pain that their decision induced among victims. Kosovo Ambassador to the US, Vlora Citaku, and former foreign minister Petrit Selimi posted a number of tweets in which they expressed their strong dismay over the committee’s decision. Citaku hashtaged the writer Salman Rushdie and CNN war reporter Christiane Amanpour on Twitter, saying that such a decision is “a slap in the face of all the victims of #Milošević regime” and urging them to join in the protest (which they did).

Politicians were not the only actors fuelling the Handke debate in the region. Uran Shuska, a Kosovo-born IT manager living in Canada, started a petition on change.org to revoke the Nobel Prize from “an apologist for the ‘butcher of the Balkans, Slobodan Milošević’”. For Shuska, anyone defending “such a monster” should not be awarded any recognition, especially not a Nobel Prize. With the number of signatures rising in thousands, news about the petition made it quickly into the mainstream media. In the Kosovo daily Gazeta Express, Shuska explained that he launched the petition in order to mobilize people to take a stand against a morally corrupt winner. Although this petition was doomed from the beginning because the rules of the Swedish academy do not allow for a decision to be revoked, it was widely shared on social media, and by the end of January it was signed by 58,997 individuals.

For genocide survivors and different victims’ organizations in Bosnia, awarding the Nobel Prize to a genocide denier was unacceptable. They organized protests in front of the Swedish embassy in Sarajevo, and sent protest letters to the Nobel Committee expressing their revulsion with Handke’s relativization of the ICTY judgments. In the response, the chair of the Nobel Committee for Literature, Ander Olsson confirmed that the ICTY verdicts provide “an essential part of the understanding of Europe’s tragic history” adding that the Swedish Academy “believes that in an open society there must be room for different opinions about authors and that there must be space for different reasonable interpretations of their literary works”. In the report about the Srebrenica genocide denial published by Potočari Memorial Centre just two months before the 25th anniversary commemoration, Monica Hanson Green notes that with this explanation the committee “openly endorses Handke’s political stance in [the] denial of genocide as one of many valid ‘different opinions’ on the established facts and judicial rulings of the highest international courts”.[12] The report widens the circle of those complicit in the act of denial to include all those in attendance at the ceremony, the Swedish monarchy itself, members of the orchestra playing at the ceremony, and “the vast majority of the Western intellectual establishment who either openly endorsed or failed to speak out against Handke’s shameful nomination”.

The participation of politicians and victims’ organizations in the debate widened not only the circle of genocide deniers, as in the report by the Potočari Memorial Centre, but also that of the genocide charges. While the ICTY judgments confirmed genocide in the Srebrenica case, the accusations of support for Serbian genocidal policy was now used for crimes committed in Kosovo as well, reaching beyond the legal qualifications and verdicts made by the court.

For critics and supporters alike, Handke’s political stance is interpreted to be a claim about empirical facts – when he is called a genocide denier, it is because he is rebutting legally established facts about the Srebrenica genocide, but when he is being celebrated for telling the truth about Serbia he is seen as promoter of alternative facts about the war. Handke's own explanations of his public engagement do not rest on exisiting evidence or new empirical facts, but on the general scepticism toward a single, unifying view on the war in Bosnia as it was formulated in Western media. Handke often repeated that he was irritated with the one-sided reporting by Western media about the war in Yugoslavia, saying: “I knew that it was impossible, that only one side, one people were guilty of everything. I wanted to travel there and to feel all that together with them”. In his own account, it was a general epistemological concern rather than empirical evidence which led him to question Western media reports about the war crimes committed by the Serbian forces. He is guided by intellectual scepticism towards the dominant Western media discourse, questioning the uniformity and simplicity of such media reports. Handke's publishing house Surkamp took an excerpt from his book A Journey to the Rivers: Justice for Serbia, to explain Handke's controversial writing about the Srebrenica genocide (or ‘massacre’, in Handke's words):

how such a massacre is to be explained, carried out, it seems, under the eyes of the world, after more than three years of war … and further, it is supposed to have been an organized, systematic, long-planned execution. Why such a thousandfold slaughtering? What was the motivation? For what purpose? And why, instead of an investigation into the causes (“psychopaths” doesn’t suffice), again nothing but the sale of the naked, lascivious, market-driven facts and supposed facts?

This paragraph encapsulates what Handke repeated in many interviews and texts in response to the accusations made against him for downplaying Serbian war crimes – that he was bewildered and irritated by the simplified and biased reporting of Western media about the war in former Yugoslavia. He questioned these reports, not on the basis of new evidence, but on the improbability of the meta-narrative itself. In his reading, the synchronized denouncement of the Serbian atrocities did not contribute to the creation of knowledge about the atrocities, but prevented the public from understanding the war, its causes and consequences. Moreover, it made it impossible to find a reasonable explanation for the war that considered the Serbian side. Unless, in a much simplified reading, the Serbs were turned into bloodthirsty monsters and psychopaths, the crimes committed made little sense. This realization was, according to Handke, one of his main motivations to engage with the war and to discover what was behind the media representations of the conflict.

Handke offered the same kind of Pyrrhonean scepticism to explain his relationship with Slobodan Milošević, rejecting accusations that he was his friend or supporter: “I don’t have an opinion (stav) about Slobodan Milošević, and I refuse to have it”.[13] Similarly, he rejected accusations that he was defending Serbia, explaining: “when they connect me with Serbia that is unfair. I went there because of Yugoslavia”. Handke repeatedly spoke about his personal relation to Yugoslavia – in his own words: “I am Yugoslav on my mother’s and uncle’s side ... My grandfather voted in the referendum in Koruška for the accession to Yugoslavia. Yugoslavia meant something to me”. Still, and the journalist did not fail to notice, the subtitle of his book is “Justice for Serbia”, rather than for Yugoslavia. Handke answered that he still considers that a right subtitle, because “the reporting about Serbia was monotonous, one sided”.

Equating Serbia with Yugoslavia is not Handke’s invention; indeed, much of the Serbian nationalist narrative (and its appeal among voters in Serbia) rests on this equation. Throughout the war and also in the ICTY proceedings, Milošević reiterated that he was defending Yugoslavia. The atrocities committed at the beginning of the war in Croatia and Bosnia contradict this account only if victims are portrayed as innocent civilians rather than separatists and terrorists. In the Serbian media during the war, the position of innocent civilians was reserved only for Serbs, thus producing the same kind of bias images that Handke so adamantly despised with regard to the reporting by Western media. In other words, the Western journalists who mainly reported on the crimes of the Serbian forces, while only reluctantly mentioning the crimes committed against the Serbs, found a worthy counterpart in a nationalist Serbian media that completely ignored the facts about mass atrocities committed by Serbian forces and focused solely on Serbian victims. Looked at from this perspective, it seems that Handke simply opted for replacing one black-and-white picture (the ‘Western’ representation of the war) for another (the Serbian nationalist representation), both being generally unconcerned with the fate and suffering of individuals on all sides of the conflict. Handke was unable or unwilling to dismantle and deconstruct the Serbian nationalist narrative, and to offer the same amount of suspicion to its claims about the war. Instead, he chose to actively participate in promoting this narrative in public; to become a voice of the Serbian nationalist project, rather than the critical intellectual he imagines himself to be. If Handke’s goal was to go beyond simplistic and one-sided accounts of the Yugoslav wars regardless of the side from which they come, then he failed to do so.

Most of the critics did not accept Handke's claim about intellectual scepticism as the explanation for his political engagement. For Serbian literary critic Đorđe Krajišnik, it was not scepticism but “his ‘extravaganza,’ his anti-globalist defiance against the West” which guided Handke in this confrontation.[14] The writer Svetislav Basara, in the Serbian daily Danas, noted that the very fact that Handke accepted the Nobel Prize showed that his support for Milošević was meant as a scandal in order to seek confrontation with the Western public and thus to satisfy his thirst for world attention. Several authors – from the philosopher Slavoj Žižek to the political scientist Florian Bieber – noted that for Handke, Serbia was an idealized place of pre-modern values where his own anti-Westernism could flourish. Reminiscent of Theodor Adorno’s mocking of Heidegger’s idealization of the German peasant, who he glorified for his simplicity, perennial wisdom and connectedness to nature, this line of explanation connects the anti-modernist longing for the home (Heimat), with finding it in imagined ethnic groups. Handke’s motivation to defend Serbia – his “peat nation”, as scholar Florian Bieber called it on his blog – may stem from a leftist criticism of Western capitalism, which decodes human rights as a sign of imperialist politics; yet, it ends up supporting the radical right-wing politics of the Serbian regime and justifying atrocities committed in its name.

Contrary to other participants in the debate, the Nobel Committee insisted on the distinction between literary merits and controversial political stance of the laureate. The member of the Nobel Committee for Literature, Rebecka Kärde explained: “When we give the award to Handke, we argue that the task of literature is other than to confirm and reproduce what society’s central view believes is morally right”. Furthermore, Kärde refused to “apologize for the hair-raising things that Handke has undoubtedly said and done”, hence announcing that political position alone cannot decide about the quality and merits of the literary work. Nevertheless, the committee remained isolated in their position, as for the critics and supporters alike, debate revolved solely around Handke’s political stance. In that sense, awarding the Nobel Prize to Handke served as a trigger of yet another memory war, and a bitter reminder of the enduring conflict over contested memories of war in the region.

Katarina Ristić: The Nobel Prize Award Sparks a Memory War: The Recent Handke Debate. In: Cultures of History Forum (31.07.2020), DOI:10.25626/0119.

Copyright (c) 2020 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educationalpurposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors

Nevena Daković · 21.04.2022

Representing Trauma - Writing the Past Into the Present Through Films

Read more

Srđan Milošević · 30.10.2017

Twice Before the Court: The Judicial Rehabilitation of General Dragoljub Mihailović

Read more

Isabela Kisic · 12.09.2017

‘Lex CEU’, Anti-Soros Campaigns and the State of Civil Society in Serbia

Read more

Rena Jeremić Rädle · 25.10.2015

Remembrance in Transition: The Sajmište Concentration Camp in the Official Politics of Memory of Yug...

Read more

Ivana Dobrivojević · 23.10.2013

From the Beginning to the End 1918 – 1991. Exhibition in the Museum of Yugoslav History

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).