20. Aug 2013 - DOI 10.25626/0005

Dr Ljiljana Radonić is writing her postdoctoral thesis on "World War Two in Post-Communist Memorial Museums" at the Institute of Culture Studies and Theatre History, Austrian Academy of Sciences (APART fellowship). Her doctoral thesis on the "War on Memory - Croatian Politics of the Past between Revisionism and European standards" appeared in 2010. Recently, she published on European memory conflicts and memorial museums in several journals, e.g. the Austrian History Yearbook (2013), Nationalities Papers (2014), Jahrbuch für Politik und Geschichte (2014), and Medaon (2014).

In late 2012, Ante Gotovina and Mladen Markač were acquitted by the Appeals Chamber of the Hague tribunal (ICTY), overturning the lengthy jail sentences that had originally been imposed. In Croatia, 96 percent of the population welcomed the new verdict, and 100,000 fans gathered to greet the two generals on Zagreb's main square. The Croatian state leadership and media were largely in agreement that the acquittal meant a clean bill of health for the military operation to liberate Krajina, dubbed "Storm", and the "Homeland War" (1991-1995) as a whole, although the prime minister and president stressed that crimes committed by "individuals" would still need to be prosecuted. In Serbia, in contrast, the verdict was met with outrage. Serbian reporting was dominated by the accusation that ICTY had once again confirmed its character as a political tribunal - an assessment shared by the former Chief Prosecutor at The Hague, Carla Del Ponte. In these debates, the victims' voices were barely heard. Ante Gotovina took a surprisingly conciliatory tone; for many disappointed veterans, this made him something close to a traitor.

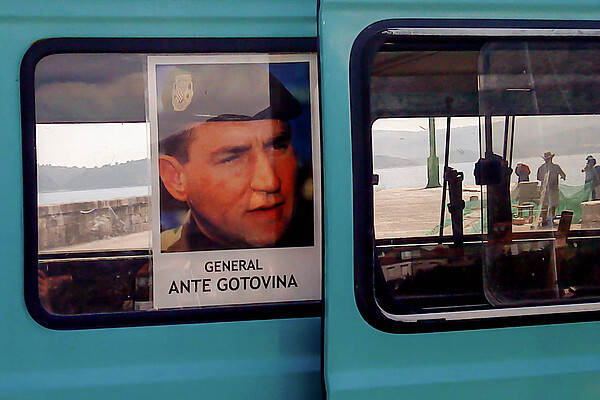

On 16 November 2012, the Appeals Chamber of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY[1]) reversed the Trial Chamber's decision to sentence General Ante Gotovina to twenty - four years' imprisonment. As well as Gotovina - the commander responsible for recapturing the Krajina region of Croatia in August 1995 after four years of Serb control - General Mladen Markač, the head of the Croatian Special Police and assistant minister of the interior, was also acquitted. This meant that the Hague tribunal had not convicted a single Croatian for crimes committed on Croatian territory.[2] Gotovina's four years on the run before being brought to The Hague had put a significant brake on the process of Croatian accession to the European Union, because the Chief Prosecutor at the time, Carla Del Ponte, accused the Croatian government of failing to fully support the arrest of the general, who was alleged to be hiding in Croatia. In late 2012, surveys showed more than 96 percent of the Croatian population welcoming the acquittal,[3] and when the heroes of the so called Homeland War (Domovinski rat) arrived in Croatia, they were greeted by an enthusiastic crowd of up to 100 000 people on Zagreb's Ban Jelačić Square. They believed that the Homeland War, as the war in Croatia from 1991-1995 is known, was now "washed clean".[4]

Eighteen years had passed since "Operation Storm" (Oluja), during which, according to the Croatian Helsinki Committee for Human Rights (HHO),[5] more than 600 Serbs were murdered, 22 000 Serb houses burned down, and more than 150 000 Serbs driven from the country. No member of the military or the Special Police has yet been called to account for Storm-related war crimes before a court - though several trials are currently pending in Croatia, for example the one concerning six civilians killed in Grubori in late August 1995.[6] However, 2380 people have been convicted across Croatia for other crimes, such as murder, rape, aggravated theft, and arson committed in the course of the operation.[7] In The Hague, six Serbs have so far been found guilty of crimes committed in Croatia; two have been acquitted; and three died during their trials, the best-known of these being Slobodan Milošević. As for crimes committed in Krajina, especially during the ferocious and bloody expulsion of all non-Serb inhabitants from this borderland region when the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK) was established, Milan Martić - the former police chief of the RSK capital Knin, later the RSK's minister of defense and foreign affairs and for a time its president - was sentenced to thirty-five years' imprisonment for murder, torture, persecution, and deportation. Milan Babić, mayor of Knin and, like Martić, later president and minister of foreign affairs as well as prime minister of the RSK, hanged himself in 2006 during his thirteen-year prison sentence. He had pleaded guilty to crimes against humanity and was going to testify as an 'insider' witness against Milošević and other Serbian defendants. At the time of writing, spring 2013, the trial was still proceeding against another former president of the RSK, Goran Hadžić, and two members of the state security service special forces unit in the Serbian (then Yugoslav) ministry of the interior.

No indictment related to Croatia has attracted more international attention than that of Ante Gotovina, who was the greatest obstacle to opening negotiations on Croatia's accession to the EU in the period between the preferment of charges against him in 2001 and his arrest in Tenerife in 2005. The son of a fisherman, Gotovina left Yugoslavia in the 1970s and joined the French Foreign Legion aged seventeen. In 1991, holding French citizenship, he returned to what was now independent Croatia and joined the Croatian National Guard.[8] He commanded Sector South during Operation Storm, and after the recapture of Krajina became commander of the Croatian Army and the Croatian Defense Council. After the death of President Franjo Tuđman (1922-1999) and the election victory of President Stjepan Mesić with the Social Democrat-led coalition under Ivica Račan in 2000, Gotovina returned to the spotlight as one of the signatories of the "Twelve Generals' Letter".[9] Angered by the arrest of five people alleged to have murdered Serbs in Gospić in 1991, the twelve generals criticized what they saw as an increasing criminalization of the Homeland War and disparagement of the Croatian Army:

We consider it inadmissible and dishonorable that the defenders and invalids of the Homeland War are only spoken about in the context of the few men who sinned against its purity or violated laws, while at the same time there is silence on everything positive and great, to which the overwhelming majority of Croatia's sons contributed."[10]

The letter called on the Croatian leadership to defend the honor and dignity of Croatian officers and soldiers. The next day, President Mesić responded by sending the six generals still on active duty into early retirement - in Croatia, members of the military are not permitted to address political statements to the public. Just a few months after the ten-year incumbency of authoritarian President Franjo Tuđman and his Croatian Democratic Union (Hrvatska demokratska zajednica, HDZ) had come to an end, this public protest by the "heroes of the Homeland War" threatened to destabilize a government now portrayed as "traitors", "bolshevists", and un-Croatian.[11] In late March 2013, Gotovina let it be known how he would be spending his future in freedom: he plans to farm tuna in Dalmatia.[12]

The two generals charged along with Ante Gotovina, Ivan Čermak and Mladen Markač, gave themselves up in 2004 when the ICTY indictment was issued. Čermak, commander of the Knin garrison during Operation Storm, was acquitted by the Trial Chamber in 2011. Markač and Gotovina were found guilty of a "joint criminal enterprise" to permanently expel the Serb population from the Krajina region. According to the first judgment, the two men had planned and prepared the operation during a meeting of all those responsible in Brioni a few days earlier, ordered unlawful artillery attacks on Krajina towns, and failed to take adequate steps to prevent or punish crimes against the Serb population. On 15 April 2011, they were convicted of crimes against humanity (persecution, deportation, murder, and inhumane acts) and of plunder and the destruction of public and private property. Gotovina was sentenced to twenty-four years, Markač to eighteen years of imprisonment.[13]

A year and a half later, on 16 November 2012, the Appeals Chamber acquitted the two generals on the charge of joint criminal enterprise. According to the new judgment, the Trial Chamber had not justified its definition of a single 200-meter standard for all four Krajina towns based on analyses of the impact of artillery fire from particular positions: the court had declared all shelling to be unlawful if it had caused destruction more than 200 meters away from legitimate military targets, but adequate grounds for this criterion had not been provided.[14] All five of the appeal judges agreed on this point. Three of the five also concluded that artillery attacks defined as unlawful by means of the 200-meter standard had been the touchstone of the "joint criminal enterprise" accusation. Once that part of the judgment fell, they decided, it was no longer possible to prove a conspiracy to expel the Serb population. On the question of whether, this aspect of the indictment having been abandoned, charges could now be entered against the two appellants on alternate grounds, they found that this was not an option. The prosecution briefs had addressed the possibility only in a footnote, the Trial Chamber had not investigated it sufficiently, and the Appeals Chamber was not in a position to seek large amounts of new evidence since the defendants would no longer have the opportunity to appeal. The severe sentences were therefore completely lifted and the appellants released with immediate effect. The appeal judgment portrayed the Trial Chamber in rather harsh terms as misguided, its verdict as insufficiently reasoned and extremely dubious. Two of the five appeal judges submitted dissenting judgments, calling the majority decision of their colleagues a "fatal error" with which they fundamentally disagreed, since the verdict contradicted "any sense of justice."[15]

The Appeals Chamber judgment gave the appearance of being arbitrary, and it was ill-suited to encouraging a self-critical confrontation with war crimes within the successor states of the former Yugoslavia, as I will show in the following survey of the debate.

If the surveys are to be believed, the whole of Croatia rejoiced over Gotovina's release. Yet the general himself, celebrated as a hero, played a rather surprising role thereafter. The less well-known General Markač told 100 000 supporters on Zagreb's main square that he had always carried the homeland in his heart, and "the homeland is you."[16] He expressed his happiness that every Croat abroad would now be able to say "we" liberated the homeland without, as he repeated twice, "the smallest stain on our reputation." Gotovina's tone was very different. He noted soberly that the war was over and the time had come to look to the future, "all of us together." Unexpectedly, he thanked the Social Democrat president and prime minister, along with the ministers of defense, justice, and foreign affairs in the new center-left governing coalition, whom his supporters had frequently denounced as traitors. On the day of his return from The Hague, this brought him boos and catcalls from his mainly right-of-center audience. Gotovina gave his first interview a few days later, to a Belgrade newspaper.[17] In the tape of the telephone conversation, he sends a message to the Serbs driven out of Croatia, saying they should come back because Croatia "is their homeland just as it is mine." Challenged by the journalist to explicitly invite them to return, Gotovina answers: "How can I invite somebody to return to his house? It is their house. ... It is not more my house than theirs. The people who have a house here and want to come back don't need to be invited by me. They should come back."[18] The journalist asks Gotovina if he would advise the institutions to prosecute the crimes committed during Operation Storm; his response that it is not up to him to tell the institutions how to do their job. He is, he says, "an ordinary citizen of Croatia, like every other, whether he be Hungarian, Italian, Russian, Serb, or German, this is their homeland just as it is mine."[19] He caused further surprise during a speech in Zadar, when he emphasized that the city had been defended by citizens of many different nationalities.[20]

When Gotovina returned to Pakoštane, the Dalmatian municipality on the Croatian coast where he grew up, 30 000 local people and visitors chanted "Ante, Ante, Ante." He answered that after eleven years away he had finally found his way home - he was happy, his friends should be happy too, and this was their evening of victory. He thanked the crowd for the "Christian love" they had shown him, and called on them: "We must continue to spread this Christian love that we have shown, so that tomorrow we will see that every person here in our homeland lives happily and feels happy."[21] Instead of attending the commemorations of the 1991 battle for the city of Vukovar in eastern Croatia, as Markač did, Gotovina preferred to make a pilgrimage to the Black Madonna at Marija Bistrica.[22]

Gotovina's restrained appearances after his seven years in jail perplexed his supporters. Ever since 2001 many villages, especially along the Dalmatian coast, had been erecting notices with his portrait and the declaration that Gotovina was "a hero not a criminal", often supplemented by the note that President Mesić and Prime Minister Račan were traitors because they had cooperated with the tribunal and, in Mesić's case, testified there on several occasions. A headline in the Zadar-based newspaper Hrvatski list[23] ran: "The people asks: Is this our Gotovina?" The editor-in-chief concluded that Gotovina was talking more like "a religious missionary, an NGO activist, or a pacifist internationalist."[24] At a concert in Split to honor the release, radical nationalist and anti-Serb singer Marko Perković, aka "Thompson"[25] (who has repeatedly denied that he sang an Ustasha song that mocks those murdered at the Jasenovac concentration camp, although proof is constantly reappearing on video), argued Gotovina "did not mean that he believed in the Croatian institutions; he feels the same way as we do." Perković added: "We have to settle accounts with the traitors."[26] The "Movement to Stop the Persecution of Croatia's Defenders" accused Gotovina himself of treachery, for "even if it comes from Ante, it's too much!" Ante was not, they complained, willing to work with them to create the state - an uncompromising, thoroughly Croat state - for which they had fought, while the nation was now reduced to rummaging through trash in order to survive, and doing so "in the shadow of gays and lesbians who parade through Croatia shoulder to shoulder with the representatives of the current government."[27]

Not only did those government representatives join the Zagreb gay pride march after the attack on the Split Pride event on the Dalmatian coast, which is what the commentary above alluded to, but their response to the generals' acquittal was guarded. Its tenor was that Gotovina's exoneration was important for Croatia because he must not be made a scapegoat for individual, genuine war criminals. Prime Minister Zoran Milanović first reminded the public that the judgment was based on only a narrow majority, showing there was a very fine line between lawful and unlawful. "Two innocent people evidently stood before the court, which does not mean that the war was not a bloody one and that no mistakes were made, but the responsibility for that is borne by the state and not by Gotovina und Markač."[29] President Josipović stressed the importance of the court having established that there had been no joint criminal enterprise.[30] Nevertheless, he continued, crimes had been committed that must not be glossed over, and a state under the rule of law was obliged to punish those responsible, whether they were Croats, Serbs, Chinese, or anyone else.[31] This statement is ambivalent: on the one hand, it indicates that any discussion of Croatian crimes must also include a reference to Serbian ones; on the other, it could also be understood as an appeal for a universalist administration of justice for which it would be irrelevant whether or not an alleged war criminal belonged to one's own community. Josipović went on to stress that the individuals responsible for murders, wrecked and burned-down villages, plundered property, and other crimes against "our Serb fellow citizens" must be brought to justice. As for the view expressed by the Croatian daily Jutarnji list[32] that Croatia could now join the EU free of any historical burden and without the taint of a criminal enterprise, Josipović pointed out that EU accession obliged a country to develop the rule of law, to protect minority and human rights, and to foster a regional and European policy of reconciliation. However, he closed by commenting that the acquittal also absolved Franjo Tuđman, who had played an important role in that period, from the political legacy of the past.[33]

Former president Stjepan Mesić - who had pensioned off the generals in 2000 after their open letter, testified in The Hague, and promoted the prosecution of war crimes during his presidency[34] - differed from his successor by insisting that the appeal judgments in no way justified an amnesty for Tuđman's policies. Mesić also expressed his surprise at those Catholic clergy who believed that their prayers and the church had contributed to the generals' release: How could clerics' prayers before the pronouncement of the judgment have had the desired effect given that the judgment was written six weeks before its delivery? "And if we are going to count through the judges, it was a Jew, a Turk, and a Protestant who voted for the acquittal, whereas two Catholics advocated imprisonment. I don't know - there seems to have been a fault on the line."[35] With regard to the furious Serbian reactions to the acquittal, Mesić added that unlike Germany, Serbia had not experienced a catharsis: Germany was a paragon "of severely punishing neo-Nazi incursions, of democracy, and of commitment to the European unification process", whereas Serbians were condemning Milošević not so much for his intention to expand Serbian frontiers as for having failed to fulfill that intention. At the same time, they were portraying the nationalist Draža Mihailović, leader of the Chetniks in World War II, as an antifascist hero.

The leadership of the Republic of Serbia reacted to the Gotovina and Markač acquittals by suspending the planned transfer of evidence to the tribunal, and more generally Serbian cooperation was reduced to the level of pure technicalities. The Serbian prime minister, Ivica Dačić, described the verdict as confirming the "claims of those who say that the Hague tribunal is not a court and that it completes political tasks that were set in advance."[36] Serbian President Tomislav Nikolić said: "It is now quite clear the tribunal has made a political decision and not a legal ruling. Today's ruling will not contribute to the stabilization of the situation in the region and will open old wounds"[37], adding that the decision had painted the Serbs in Croatia as perpetrators even though, especially in Krajina, they had been victims of the worst pogrom since World War II.[38] In the Serbian media just as in Croatia, then, the public debate unfurled along familiar narratives of victimhood. Serbian commentators also highlighted the Croatian population's euphoria at the acquittal and the fact that Croatia had immediately sent a plane and two government ministers to collect the former generals from The Hague.[39]

For many weeks, the media were full of reactions from Croatian and Serbian politicians, but they carried almost no responses from the victims of Operation Storm. In a rare piece of coverage, Rade Matijaš from Knin recounted feeling "terrible and miserable",

slapped in the face by the whole world and the international public through the Hague tribunal. Ever since this morning [16 November], we people from Krajina have been asking each other: 'Did I really murder my own neighbors and friends, did I really set fire to my own house and then walk off, going to Serbia or into exile just for fun?' The questions are terrible, irresolvable, and there is no answer. So on Sunday we are going to do the only thing we can do: light a candle and pray to God, because there's no one else left for us."[40]

The Chief Prosecutor of the tribunal at the time, Carla Del Ponte, told the Belgrade newspaper Blic that she felt great solidarity with the Serbs against whom crimes had been committed. She described the acquittal as "not justice", and said she was "shocked", "very surprised", even "stupefied". She speculated that the acquittal might have been driven not by evidence, but in part by politics, lobbying funds, or something else.[41] The Croatian paper Novi list, in turn, criticized Del Ponte's statements, arguing that she

"most certainly bears the greatest responsibility for the catastrophic failure of the Hague prosecutors: it was thanks to her megalomania and politicking that the prosecutors neglected and abandoned the victims during and after Operation Storm and instead went chasing after an imaginary "joint criminal enterprise" led by the late Franjo Tuđman, rather than pursuing those responsible for the actual and specific crimes .... The prosecution did not even attempt to prove the aspect of Gotovina's and Markač's responsibility as commanders, being sure that the Hague judges would swallow this megalomania. However, they did not."[42]

Of course, in both Croatia and Serbia there were also distinguished critics of the predominant nationalist discourses. For the most part, these were people who had been attacking euphoric hero-worship and victim narratives since the 1990s within civil rights initiatives, critical journals, and so on. In the following, I outline the discussion of the Gotovina case that took place on the website of the Peščanik association, Belgrade.[43] It exemplifies these processes, with critical comments on the generals' acquittal from both Croatia and Serbia. The contributors joined in concluding that the judgment would have a negative impact on neighborly relations both individually and nationally, and in finding the Croatian nationalist discourse of victory more toxic than the Serbian discourse of defeat. It is particularly remarkable that the authors from Serbia take up a critical stance toward the mechanisms of Serbian society's self-victimization. Law professor Marko Milanović does not spare his own community, deeming the Serbian leaders to have been the worst criminals during the wars of the 1990s.[44] And lawyer Bogdan Ivanišević emphasizes the complexity of the case:

"Those convinced that the Serb civilians were victims of deportation should be aware of the fact that an overwhelming majority of the Serbs fled before there was any physical contact between them and the Croatian army and police. In that respect, the case differed from numerous other cases in which the ICTY dealt with crimes of forcible transfer or deportation."[45]

In this commentary, something that is often dismissed as no more than a Croatian defense strategy is proposed as a genuine and important circumstance, in order to counter overly simplistic narratives.

Of the contributions from Croatia, among the most interesting is one by Viktor Ivančić, formerly a journalist on the Croatian weekly Feral Tribune. He describes the unbearable pitch of Croatian euphoria with a satirical flair that recalls the style of the Tribune and vividly evokes his frustration at the prevailing mood. Ivančić cites countless heroizing portrayals in Jutarnji list, including its pull-out poster of Gotovina, but most of all the tendency to brand as traitors everyone who insists on the need for further trials, such as Milorad Pupovac or Zoran Pusić.[46] On the portal, Pusić, president of the Civic Committee for Human Rights (GOLJP), and Žarko Puhovski, former president of the Croatian Helsinki Committee for Human Rights, both stress that a disastrous mixture of triumphalism and conspiracy theories is dominating Croatian discourse on the Gotovina trial. Pusić's contribution, entitled "How to Prevent the Judgment Condemning Us to New Conflicts", is particularly critical of a parliamentary deputy's call, after the acquittal, for two further war crimes trials to be annulled or abandoned. Instead, Pusić argues, Croatian politicians must now take the initiative to begin a process of reconciliation and reparations. They must act rationally and with empathy, since on the Serbian side the implication that basically no crimes were committed at all is resulting in frustration that could easily tip over into hatred. Pusić regards the action now taken by official Croatia as crucial to future relations between Croats and Serbs.[47] Contributors from both countries agree that the acquittal will lead to further marginalization of those calling for all the crimes committed to be rigorously investigated and prosecuted without regard for "patriotic" feelings.

Despite this wide spectrum of assessments, Gotovina was made an honorary citizen of some Croatian towns. The first to do so was Split, where Gotovina had once been military commander; it was followed by Zadar, Osijek (which honored Markač as well), and Dubrovnik. In contrast, the urgent appeal to the Croatian judiciary that Croatian civil rights organizations published in 2011 after the original verdict, calling for full prosecution of the crimes committed during and immediately after Operation Storm, has not borne any fruit so far (although trials are still under way). For example, the murder of at least ten men and women aged around eighty in Golubić near Knin on 6 August 1995, remains unpunished. So does the attack on a refugee convoy on 7/8 August, in which several dozen, mainly elderly men and women riding tractors were killed by shots from nearby woodland or shelling; nine civilians murdered in the village of Komić near Korenica on 12 August, including a 74-year-old woman burned alive in her house; seven civilians murdered in Kistanje on 27 August (the indictment issued in 1996 was dismissed for lack of evidence and the case went back for fresh investigation against persons unknown; since March 2012 five new defendants have been on trial). In the case of nine people aged between sixty and eighty-five who were killed in Varivode on 28 September 1995, six police officers were acquitted and investigations began again against persons unknown - still without results, ten years after the not guilty verdict.[48]

Since late 2011, a Social Democrat-led coalition has been in government in Croatia, succeeding the HDZ, which had been in power almost without interruption since 1990.[49] The country was internationally isolated during the 1990s due to President Frano Tuđman's active support for aspirations in the Croat part of Bosnia and Herzegovina to join the "motherland" and revisionism with regard to the wartime Ustasha regime and its collaboration with the Nazis in Croatia.[50] Although the HDZ prime minister Ivo Sanader pursued an unambiguously pro-EU course after taking office in 2003, he reactivated hostile stereotypes from World War II on several occasions in 2005, when he implicitly described "the Serbs" as the fascists of the 1990s conflict and Croatia as "the new Jew".[51] In contrast, Vesna Pusić, the deputy prime minister and minister of foreign affairs with responsibility for overseeing the negotiations on Croatia's EU accession, was already a proven critic of the HDZ's policies on Bosnia - and on Croatian history - as early as the mid-1990s,[52] a time when the Croatian public sphere was far from being a forum for pluralist debate.

It remains to be seen whether anything comes of the promises to do everything necessary to call the "real" culprits of the crimes to account. There was a revealing incident in spring 2013, when more than 20 000 people in the Croatian city of Vukovar - devastated in 1991 - protested the reintroduction of Cyrillic script as the second official script in towns and villages where Serbs make up more than one third of the population. The words of the leader of a group of the "defenders of Vukovar" show how deeply day-to-day politics is still entangled with the past: "that was not what we fought and died for", he said.[53]

Ljiljana Radonić: The Acquittal of the Croatian Generals Ante Gotovina and Mladen Markač. In: Cultures of History Forum (20.08.2013), DOI: 10.25626/0005.

Copyright (c) 2013 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

Ljiljana Radonić · 11.06.2019

Commemorating Bleiburg – Croatia’s Struggle with Historical Revisionism

Read more

Maciej Czerwiński · 07.11.2016

Croatia's Ambivalence over the Past: Intertwining Memories of Communism and Fascism

Read more

Tamara Banjeglav · 12.04.2015

A Storm of Memory in Post-War Croatia

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).