11. Jun 2019 - DOI 10.25626/0100

Dr Ljiljana Radonić is a postdoctoral researcher funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF - project nr. V663-G28) at the Institute of Culture Studies and Theatre History at the Austrian Academy of Sciences and she is teaching at the Department of Political Science, University of Vienna. Her research focuses on representations of the Second World War in post-Communist memorial museums. Moreover, in 2018 she received an ERC consolidator grant working on "Globalized Memorial Museums. Exhibiting Atrocities in the Era of Claims for Moral Universals."

For many Croatians, Bleiburg – a town not even located in Croatia, but in Austria, near the Slovenian (formerly Yugoslav) border – is a central site of memory. Every year in May, several thousand Croats gather there to commemorate the so-called ‘Bleiburg tragedy’ which occurred at the end of the Second World War. The Documentation Centre of Austrian Resistance (DÖW) has called these commemorations “the biggest neo-Nazi meeting in Europe”.[1] Yet, only in March this year the Catholic Church in Austria (the bishopric of Gurk-Klagenfurt) withdrew its permission to hold a holy mass, as had been transpired in previous years as part of the commemoration ceremony. Despite this set-back, the commemoration once again took place on 18 May 2019, with robust support from the Croatian government. The Croat organizers argued that the event takes place on private property and that the Church only withdrew the right to hold an episcopal mass, not a simple mass. However, days before the event, Austrian authorities rejected this interpretation, describing the event as an assembly, and not a church ceremony. As a result, the sermon of the bishop of Krk was dubbed “a speech”. Though fewer than expected, about 10 000 visitors attended the event, including the Croatian ministers of administration, Lovro Kuščević, and defence, Tomo Medved. But what does ‘Bleiburg’ actually stand for? What is its greater meaning in Croatian memory politics and how did this place become a symbol for historical revisionism in contemporary Croatia? The article seeks to provide historical and political context to the current events and ongoing struggles of Croatia’s political elites and society with the country’s complicated past.

The so called ‘Independent State of Croatia’ was a fascist Nazi satellite state that existed from 1941 to 1945 and was led by the Ustaša, an extremist anti-Serb, antisemitic and anti-Roma movement. At the end of the Second World War, German Wehrmacht soldiers, Croatian Ustaša, regular members of the Croatian army (Domobrani) and civilians, Serbian royalists (Četniks), Slovenian Nazi collaborators (‘White Guards’) among others all fled from the victorious Yugoslav partisans, hoping to surrender to the British Army near the Austrian town of Bleiburg. The British refused their surrender and extradited most of these people from Yugoslav territory to areas controlled by Tito’s partisans. Although the number of the victims remains uncertain, it is possible to say that during the battles with the partisans on the journey to Bleiburg and on the forced march back into the country after 15 May 1945, tens of thousands of Croat Ustaša, Domobrani, and civilians were killed, most of them in Kočevski rog and Tezno in Slovenia, and on the so-called ‘way of the cross’ or ‘death marches’ – as the several-hundred kilometre long marches are referred to in contemporary Croatia.[2] Any mention of these events became taboo after 1945, or was only addressed vaguely as a battle against ‘collaborationist guerrilla’.

The victims of the partisans’ illegal mass killings which would come to be known as the ‘Bleiburg tragedy’ were, to a large extent, Ustaša perpetrators, yet in Croatia after 1990 they were often referred to as the “innocent victims of the Way of the cross”. As the fleeing platoons began to leave Croatia on 5 and 6 May 1945, they were under the command of Vjekoslav Maks Luburić, who had previously been responsible for the Ustaša concentration camps, including the infamous Jasenovac extermination camp complex. On 11 May, Luburić returned to Zagreb to continue the guerrilla fight; two Ustaša generals, Ante Moškova and Tomislav Rolf, took over the command. Rolf had previously participated in the confinement (and subsequent murder) of Serb peasants in the church of Glina in the summer of 1941. In present day Croatia, commemorating the murdered as the victims of partisan crimes has always come hand in hand with a historical revisionism regarding the crimes of the Ustaša and the open display of Ustaša symbols during the event.

Despite this fact, the HDZ (Hrvatska demokratska zajednica – Croatian Democratic Union), the dominant party in Croatian politics since the country’s independence in 1991, has traditionally supported the Bleiburg commemorations. This was particularly so during the presidency of Franjo Tuđman during the 1990s; it became slightly less tangible during the EU accession talks under HDZ prime ministers Ivo Sanader and Jadranka Kosor (2003 to 2011), and has been resumed with renewed enthusiasm after Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović became president in 2015 as both the President and Prime Minister are now from the HDZ. In the early days of independent Croatia, the HDZ and president Tuđman took an ambivalent stand on the Ustaša regime: They tried to distinguish between the “Independent State of Croatia” (1941 to 1945), which they understood as a milestone towards Croatian independence, on the one hand, and Ustaša crimes, on the other hand. This distinction, however, makes about as much sense as distinguishing between the Third Reich and the National Socialists. The “reconciliation” formula proposed by Tuđman, a former historian, argued that both the Ustaša and the partisans had fought for the “Croatian cause” during the Second World War – albeit in different ways. He went so far as to suggest burying the bones of Ustaša members killed after ‘Bleiburg’ at the site of the largest Ustaša death camp, Jasenovac, in order to achieve “national reconciliation” between the victims and the perpetrators of Ustaša atrocities.

While the Croatian parliament traditionally acts as the patron of the Bleiburg event, higher ranking politicians tend to visit Bleiburg a few days before the official event in order to avoid the bad publicity of being seen together with the mass of Ustaša symbols that dominate the commemoration. From 2000 to 2003, a period during which Croatia was not governed by the HDZ, the social-democratic government – under massive pressure from right-wing circles and veterans of the 1990s war – nonetheless went to Bleiburg a few days after the 2002 commemoration, despite the fact that social-democratic Prime Minister Ivica Račan was one of the few officials to oppose the use of the term “way of the cross” for the Bleiburg related marches.[3] That same government decided in 2003 to purchase land in the Loibach area close to Bleiburg to erect a more elaborate memorial. Only the following social-democratic prime minister, Zoran Milanović, and the ruling “Kukuriku” centre-left coalition (2011 to 2016) distanced themselves from the commemorations at Bleiburg. They withdrew the parliament’s patronage of the event in 2012 and cut off state financing in 2013. The successive centre-left Presidents – Stjepan Mesić (2000-2010) and the somewhat less out-spoken Ivo Josipović (2010-2015) – were crucial for re-establishing the legitimacy of an anti-fascist stance, in response to the authoritarian Tuđman-era during which the state’s claim to an antifascist tradition was often reduced to mere lip-service.

In January 2016, a former vice-president of the Honorary Bleiburg platoon (Počasni bleiburški vod) known for his historical revisionist views became the minister of culture for the HDZ. As such, Zlatko Hasanbegović was in charge of the Jasenovac memorial complex at the former Ustaša death camp, 100 kilometres southeast of Zagreb. Not surprisingly, he has pushed for the re-establishment of the parliament’s patronage of Bleiburg, while simultaneously arguing that the state’s support for the annual commemoration in Jasenovac was a “problem” since “it is not about the commemoration of the victims or the condemnation of perpetrators, but it is misused for the rehabilitation of Yugoslav communism”.[4] This HDZ-led government’s first months in power created the impression that Croatia was following the lead of Fidesz in Hungary and PiS in Poland, attacking democratic checks and balances, evoking anti-European sentiments and half-heartedly concealing its historical revisionism. But after a no-confidence vote against the prime minister, considered a marionette of the HDZ party leader Tomislav Karamarko, new parliamentary elections were carried out in September 2016, the results of which saw the same parties re-forming a coalition, albeit now with more Europe-friendly faces in cabinet, now led by HDZ Prime Minister Andrej Plenković and missing Hasanbegović.

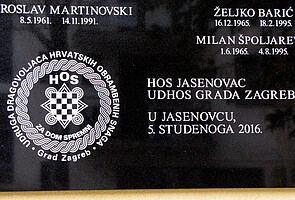

One recent scandal concerning the marginalization of Ustaša crimes occurred when Plenković was already in power: A former paramilitary organization founded in 1991, the “Croatian Defence Forces” (Hrvatske obrambene snage – HOS), and absorbed into the Croatian army in 1992, erected a memorial plaque for its fallen members in the town of Jasenovac next to the former Ustaša concentration camp in November 2016. Its emblem contains the motto ‘Ready for the home(land)’ (Za dom spremni), the Croatian pendant to the Nazi-salute ‘Sieg Heil.’ After heavy protests, the plaque was removed in 2017 – or to be more precise, it was relocated to Novska, a bit further away from Jasenovac. The Jewish and Serb communities have boycotted the official annual commemoration at the Jasenovac memorial site ever since. The head of the Jewish community in Croatia argued at a counter-commemoration in April 2019 that there will be no shared commemoration until the slogan “Za dom spremni” is forbidden by law.[5]

Responding to the public outcry over the commemorative plaque, the HDZ government appointed a special “Council for Confronting the Consequences of the Rule of Undemocratic Regimes” (Vijeće za suočavanje s posljedicama vladavine nedemokratskih režima), a state-sponsored body of academics from different Croatian institutions of higher education, in March 2017. Its official mission was “to produce comprehensive recommendations aimed at dealing with the past, as well as recommendations for the legal regulation of the use and emphasis of features, signs and symbols of non-democratic regimes.”[6] In March 2018, the Council ruled that the use of the slogan ‘Ready for the homeland’ was illegal according to the Croatian constitution, but could be used in exceptional cases like in the HOS emblem as it may have initially been an Ustaša greeting, but was later also the motto under which Croatian defenders died during the Homeland war in the 1990s. The prime minister supported this decision. The Croatian president first argued that it was an old Croatian greeting, but in February 2019 was forced to admit that this was not the case.[7]

Historical revisionism in Croatia has recently drawn international criticism, for example in a report edited by William Echikson as part of the “Holocaust Remembrance Project: How European Countries Treat Their Wartime Past”, published by the Institute for Jewish Policy Research in January 2019. One of its key findings is that

revisionism is worst in new Central European member states – Poland, Hungary, Croatia and Lithuania. […] Driven by feelings of victimhood and fears of accepting refugees, and often run by nationalist autocratic governments, these countries have received red cards for revisionism.

While the finding about revisionism is definitely accurate, there is still a decisive difference between the situation in Poland and Hungary, where governments actively seek to curb media freedom and the rule of law, and that of Croatia. If we argue that memory politics always serves present-day purposes, it is crucial to distinguish between governments that have an ambivalent stance towards a collaborationist regime during the Second World War and those that pass ‘memory laws’ that punish those who claim “that the Polish Nation or the Republic of Poland is responsible or co-responsible for Nazi crimes committed by the Third Reich”.[8] Echikson’s overly simplistic comparison between the so-called “worst offenders” (cases of alleged revisionism) such as Croatia and seemingly ‘exemplary’ cases like Romania or Austria (which was ruled by a coalition including the far-right Austrian Freedom Party until a few weeks ago) is problematic. With regard to the former concentration camp in Jasenovac, the report states:

Despite honest efforts to get at the bottom of the nature and number of victims of this and several other Ustaša-era concentration camps, the government has failed to organize an international commission on the Holocaust in Croatia, on the model of the Eli Wiesel Commission in Romania.

Yet, the problem with historical revisionism in Croatia is not due to a lack of scholarly research on the Holocaust or the Jasenovac death camp. The endlessly disputed number of the victims of Jasenovac is not disputed because of a lack of profound research on this subject: The Jasenovac Memorial Site has identified 83 145 victims by name so far, and reliable scholars based in both Zagreb and Belgrade have established that up to 100 000 people were killed in Jasenovac.[9]

While there seems to be no improvement in sight in Croatia, the Bleiburg discussion has recently gained momentum in Austria – due in part to young people’s engagement with documenting Ustaša insignia at the commemoration, an informative website, as well as a theatre performance, and partially because the far-right Freedom Party is no longer in power in Carinthia/Kärnten. This development has resonated in Croatian far-right circles, to the extent that a portrait of me was included in a kind of “wanted” poster (for members of the “Anti-Croatian Austrian phalanx”) on an extremist website – together with an Austrian state radio Ö1 journalist, the former social-democratic Minister of Finance, the head of the Communist party in Austria among others. The text does not elaborate on what exactly the Croatian Pure Party of Rights (Hrvatska čista stranka prava, HČSP) does not appreciate about my “theses on Bleiburg”.

This year, Frankfurter Rundschau journalist Danijel Majić was singled out as a critic of the Bleiburg events during the ‘commemoration’. He was verbally attacked and spat on by the far-right Croatian TV show host Velimir Bujanec, before being physically attacked by Bujanec’s associates.[10] These attacks suggest that the spirit of the 2019 Bleiburg event remains unchanged. Yet its outward appearance has changed: Only one person was arrested by Austrian police for engaging in a Hitler salute; two counter-demonstrations were organized (although not well-attended); representatives of all three smaller Austrian opposition parties (the Greens, the Neos and the Jetzt party) made sure that journalists were no longer treated in a hostile way by the Austrian police as “provocateurs”; and the police itself made announcements during the event reminding the participants that it was no longer a church event and that participants were required to respect the 2019 amendment of the Austrian insignia and symbol law (Abzeichen- und Symbolgesetz) which bans two very specific variants of Ustaša symbols, which were also in use by the Bosnian 13. Waffen-SS-Division “Handschar”. In 2019, the display of Ustaša symbols thus became a marginal phenomenon at the Bleiburg commemoration for the first time.

Ljiljana Radonic: Commemorating Bleiburg – Croatia’s Struggle with Historical Revisionism. In: Cultures of History Forum (11.06.2019), DOI: 10.25626/0100.

Copyright (c) 2019 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

Maciej Czerwiński · 07.11.2016

Croatia's Ambivalence over the Past: Intertwining Memories of Communism and Fascism

Read more

Tamara Banjeglav · 12.04.2015

A Storm of Memory in Post-War Croatia

Read more

Ljiljana Radonić · 20.08.2013

The Acquittal of the Croatian Generals Ante Gotovina and Mladen Markač

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).