13. Dec 2019 - DOI 10.25626/0106

Lavinia Stan is a Professor of Political Science and coordinator of the Public Policy and Governance Program at St. Francis Xavier University, Canada. A comparative politics specialist and the recipient of numerous research grants, Stan has published extensively on transitional justice as well as religion and politics in former communist countries. Between 2017 and 2019 she was a member of the Cultures of History Forum's editorial board.

On 20 September 2019, the Bucharest Court of Appeal confirmed that Romanian politician Traian Băsescu had collaborated with the communist secret political police while enrolled as a student at the Mircea cel Bătrân Naval Institute in the southeastern town of Constanța, the country’s major Black Sea port. The court branded the former President of Romania a “collaborator of the Securitate” based on a set of newly discovered documents released by the National Council for the Study of Securitate Archives (Consiliul Naţional pentru Studierea Arhivelor Securităţii- CNSAS), the state agency that acts as custodian of the communist-era secret files. Băsescu bitterly disputed the verdict and vowed to appeal it.

The court verdict refueled public debates regarding the completeness of Romania’s transition and the nefarious involvement of communist-era decision makers in undermining post-communist democratization. By confirming long-standing allegations that Băsescu had served the communist regime as a secret spy, the verdict seriously damaged his reputation and reignited charges that he built his post-1989 political career by relying on former Securitate connections. This article positions the recent revelations into Băsescu’s secret past within the larger public debates occasioned by the 30th anniversary of the collapse of the communist dictatorship of Nicolae Ceaușescu and explains their relevance in a country that has adopted a lukewarm program of reckoning with the human rights abuses perpetrated up until 1989.

Born in 1951, Băsescu graduated from the Mircea cel Bătrân Naval Institute in 1976 and then pursued a career as a merchant marine deck officer with Navrom, the Romanian state-owned shipping company which owned approximately 290 ships of various types.[1] Starting in 1981, he served as a captain of some of Romania’s largest commercial ships. By the end of the decade the communist authorities appointed him as head of the Navrom office in Anvers, Belgium. In May 1989, Băsescu was removed from his post and recalled to Romania, where he secured a minor bureaucratic position with the Ministry of Transportation. By the time the revolution rocked the country in December 1989, Băsescu was keen to pursue a political career and to take advantage of the new opportunities offered by post-communism.

As with most other Communist Party members, Băsescu eagerly joined the National Salvation Front (FSN), which portrayed itself as the new revolutionary force committed to transforming the country into a democracy and a free market economy. In 1991, Băsescu became Minister of Transportation in the short-lived Petre Roman cabinet, a position he retained during the following year under Prime Minister Theodor Stolojan. In that capacity, Băsescu oversaw the privatization of the Romanian merchant fleet, which some deemed a necessary move designed to avoid costly reparations of outdated ships and others criticized as a corrupt move that destroyed a strategic national asset and allowed well-positioned bureaucrats and politicians to enrich themselves. When in 1992 the FSN split into the Social Democratic Party (PSD), which gathered older, more conservative former Communist Party members, and the Democratic Party (PD), which was supported by the younger, more reformist former Communist Youth Union members, Băsescu opted for the PD. He ran as a PD candidate in the 1992 parliamentary elections, securing a seat in the lower Chamber of Deputies. He was re-elected as a PD deputy in late 1996, soon afterwards being appointed again as Minister of Transportation.

A member of a junior ruling party, Băsescu survived as Minister of Transportation under the cabinets of Victor Ciorbea (1996–1998), Radu Vasile (1998–1999) and Mugur Isărescu (2000). In 1997 he gained the reputation of a politician unafraid to criticize his own government for incompetence, ready to distance himself from his party colleagues and willing to renounce parliamentary immunity in order to facilitate investigations related to his involvement in the selling of the merchant fleet. Băsescu skillfully used the mass media to attack his political opponents. His pointed criticisms led to the fall of the Ciorbea cabinet in March 1998, and the subsequent undermining of the ruling Christian Democrats’ credibility. Băsescu was elected mayor of Bucharest in 2000. That was the first election which required the prior investigation of all candidates’ past connections with the Securitate by the CNSAS.[2] Băsescu was not among those revealed as a former secret agent. In preparation for the 2004 general elections, Băsescu forged a merger of the PD and the much smaller Romanian National Party of Virgil Măgureanu. Between 1990 and 1997 Măgureanu had headed the Romanian Intelligence Service (Serviciul Român de Informații - SRI), heir to the domestic repression department of the notorious Securitate. As a result, Băsescu was accused of protecting former state security agents.[3]

In 2004, Băsescu was elected President of Romania on an anti-communist platform and with the backing of the Justice and Truth Alliance, which brought together the PD and the National Liberal Party (PNL). Many observers attributed his electoral win to the final televised debate, where he candidly told his PSD opponent Adrian Năstase that Romania’s “greatest curse” was none other than voters having to choose between two former Communist Party members like the two of them.[4] However, during the first months of his presidency a string of appointments to high government positions of well-known former Securitate officers and informers cast doubt over Băsescu’s anti-communist fervor and prompted prominent intellectuals to ask the new president to prove his commitment to transitional justice.

The Bucharest-based Group for Social Dialogue (Grupul pentru Dialog Social - GDS), which included well-known intellectuals, called for the introduction of accusation-based lustration similar to the program already in place in Germany. In contrast to the Polish confession-based lustration, which allowed post-communist public office holders to retain their posts if they admitted to their communist-era collaboration with the StB, the lustration favored by the Romanian intellectuals called for the removal of former Securitate agents (full time officers and part time informers) from public posts, if their past connections were demonstrated by archival documents. For intellectuals like Sorin Iliesiu and Gabriel Liiceanu, only lustration leading to job loss could cleanse the post-communist political elite of the corrupt and undemocratic former spies who used their hidden connections to keep the country a prisoner of their individual and group interests.[5] Unfortunately, Law 187/1999 had designated the CNSAS as the sole custodian of the Securitate files and investigator of communist-era ties to Securitate without compelling the intelligence services to physically transfer the documents to the new agency and without providing for the dismissal of those named as former secret informers in Securitate documents. This is why in 2000 and 2004 the CNSAS investigations failed to block the election and subsequent nomination of former spies to positions of power and influence, ranging from cabinet and parliament members to leaders of public utilities, mass-media trusts, universities and science academies, among others.

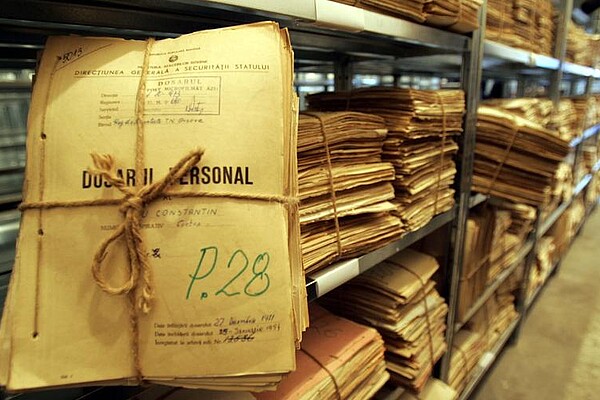

As President Băsescu dismissed the idea of a harsh lustration, the GDS requested the transfer of all Securitate files to the CNSAS and the creation of a presidential truth commission. Responding to these concerns, in 2005 Băsescu ordered the SRI to relinquish more than one million secret files inherited from the Securitate. The same files had been declared secret in late 1999 under President Emil Constantinescu due to unspecified “national security” concerns. The transfer gave the CNSAS direct access to most of the documents housed by the SRI, but not to those inherited by the External Intelligence Service (Serviciul de Informatii Externe - SIE), heir to the foreign espionage department of the Securitate.[6]

The following year, Băsescu set up the Presidential Commission for the Study of the Communist Dictatorship in Romania to investigate the human rights abuses perpetrated from 1945 to 1989 and then, based on its final report, officially condemned the communist regime in a joint parliament session.[7] That condemnation came just weeks before the country joined the European Union in January 2007. While both the secret file transfer and the final report of the commission were publicly criticized as incomplete and biased, they boosted Băsescu’s anti-communist credentials, established him as the foremost anti-communist Romanian politician, and reinvigorated the process of publicly identifying former Securitate agents.

With direct access to some 70 percent of the former Securitate archive, the CNSAS was able to reveal the former ties to the Securitate of many luminaries belonging to almost all of the major political parties. Among the scores of PD leaders who were revealed as former secret informers after the 2005 file transfer, was Minister of Culture Mona Muscă, who chose to withdraw from politics when subjected to vicious criticism by intellectuals associated with the GDS. Muscă was a vocal critic of the Securitate’s lingering shadow over post-communist Romania and a committed proponent of radical lustration, therefore her failure to disclose her own tainted past was particularly vexing for intellectuals like Liiceanu.[8]In an open letter to the disgraced politician, he faulted Muscă for trying to minimize her spying activities on behalf of the communist secret police because, as he put it, it was apparent that “the entire Securitate, from the cleaning lady who mopped the hallways of the Interior Ministry to the Securitate generals, from those who spied unofficially to the official informers with a code name (like you), all of them, my dear lady, supported the most perfect repression system.”

More importantly, none of the secret documents transferred to the CNSAS named Băsescu. While analysts alleged that sensitive documents implicating Băsescu and other top politicians were taken out of the transfer in order to be kept locked and out of the public eye, Băsescu continued to insist that no additional documents related to him were found simply because he never spied.[9] Indeed, the list disclosed in 1992 had only hinted at, but did not substantiate, Băsescu’s collaboration with the Securitate. According to Law 187/1999, collaboration is demonstrated only by notes with information on others that are signed by the secret informer or summarized by the secret officer. Such a proof emerged only in 2019.

In an unexpected twist, the official condemnation of communism put an end to state-led transitional justice in Romania and Băsescu’s support for reckoning programs. Lustration with loss of job was never adopted and the president ignored many of the commission’s recommendations. After 2008, the CNSAS lost the right to brand individuals “Securitate collaborators”; instead, only the courts could make such a pronouncement based on information supplied by the CNSAS. Băsescu twice survived an attempt by parliament to suspend him in 2007 and 2012 and renewed his presidential mandate in 2009. But his divisive leadership style, frequent attacks against both political friends and political foes, disregard for procedure, propensity to promote close relatives into positions of power, and unflinching support for shady characters like Elena Udrea greatly delegitimized him.[10] His popularity collapsed, even though his most erratic moves were still vocally defended by the anti-communist GDS. When his second presidential mandate ended in 2014, Băsescu was a minor political figure leading the newly formed but rather insignificant People’s Movement Party. The party helped Băsescu to secure a seat in the Senate in 2016 and one in the European Parliament in 2019.

As journalists pointed out when commenting on the 2019 verdict, this was the first time that Băsescu was officially declared a former secret police informer by both CNSAS and the courts. Yet, it was by no means the first time that his Securitate ties had become the subject of public controversy. Already in February 1992 Telegraf, a newspaper from Băsescu’s hometown Constanța, included his name on a list of Securitate informers recruited with the approval of the local Communist Party leaders (Registrul cu persoanele din rîndul membrilor PCR pentru care s-a dat aprobarea să sprijine munca de Securitate).[11] The list mentioned that Băsescu had been used by the Securitate as a source of information since 1977. Later that year, Băsescu admitted that he submitted information notes to the Securitate but claimed that he had nothing to feel guilty for.

In 2004, Băsescu’s past collaboration was again made public when Mugur Ciuvică revealed the name of Băsescu’s recruiter: Securitate Lt Mihai Avramides. In response, Băsescu declared that he never secretly informed on others but that during communism all ship captains, when returning to Romania from long voyages, had to provide details about the countries they visited, the persons they met, the order and discipline difficulties posed by their crew members, and the technical situation of the ship they commanded, but never the “people’s attitudes toward the [communist] regime.” Eager to clear his name, Băsescu sued Ciuvică for calumny, and the Romanian courts ultimately settled in Băsescu’s favour weeks before he won the presidential elections. When preparing the case, Ciuvică asked both the intelligence services and the CNSAS to clarify whether the presidential candidate was a former secret collaborator. The response was that he was not.

A document made public as part of that court case, issued by the Ministry of National Defense Archives, listed Băsescu as a collaborator with the Securitate’s Military Counterintelligence Direction. According to it, Băsescu had been recruited as a student of the Naval Institute to spy on his peers under the codename Petrov. The Securitate at the time closely monitored the regime loyalty of the Institute’s students and teachers because of their contacts with foreign citizens. While commenting on the document disclosed in 2004, Băsescu admitted that he provided information to the responsible Securitate officer immediately after he returned from his first sea voyage in 1972. But, he said, he informed on none of his peers and instead answered questions related to his own life, beliefs, and family – something that all Institute students had to do prior to 1989, he claimed. Journalists noted that no other student was included on that Securitate list, proof that Băsescu’s comments were untruthful. The CNSAS found that Băsescu’s denunciation infringed on the rights to privacy and mobility because they prompted the Securitate to ban one fellow student from taking a trip abroad.[12] Such human rights violations, more than the discovery of the secret information notes, warranted the labelling of Băsescu as a Securitate collaborator.

Băsescu’s comments were further disproved by former communist-era Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade Ştefan Andrei who, in a televised interview, reiterated the fact that during the communist regime no Romanian citizen could be stationed abroad without the explicit approval of the Securitate.[13]According to Andrei, appointments to jobs that required an individual to live outside of Romania for extended periods of time had to be approved by a committee appointed by the Communist Party personnel department, headed by Elena Ceauşescu, the dictator’s wife. The committee was subordinated to the Securitate, Andrei said. Băsescu’s appointment in the Netherlands required clearance from the Securitate, which in return asked Băsescu to assume unspecified responsibilities beyond those of the mere secret informer he once was as a student.

In a November 2005 interview, Avramides claimed that he met Băsescu only twice during the 1970s and denied any personal involvement in Băsescu’s recruitment as a Securitate secret agent. The interview contradicted Băsescu’s earlier claims that he never met Avramides but did not clarify Băsescu’s involvement with the communist state security.[14] As the president showed propensity to surround himself with known former Securitate agents, journalists continued to monitor the careers of the officers with whom Băsescu came in contact while abroad. Since those spying activities took place outside of Romania, the documents compiled on them are housed with the SIE, and therefore still inaccessible to the general public.

All of these revelations sparked the public’s interest. Journalists found out that, curiously, several Securitate officers who most likely came in contact with Băsescu, either in Romania or abroad, had spectacular careers after 1989. The newspaper Cotidianul (the Daily) alleged that most of these officers kept silent about Băsescu’s Securitate ties because, as minister and then president, he bought their silence in exchange for protection and promotion. According to these investigations, Dumitru Nicuşor and Constantin Decu, once with the Securitate Constanța branch, had used Băsescu as a source after Avramides was transferred to the Prison Department. After 1989, Nicuşor became head of the Ialomiţa branch of the SRI, while Decu led the Constanţa branch of the SRI. The former Securitate officer Silvian Ionescu who, in the late 1980s, supervised the Romanian spies stationed in Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxemburg was promoted by President Băsescu to head of the government’s Environmental Protection Department. Marin Antonescu, former head of the Securitate rezidentura in Brussels, was the PD vice-president of the Dîmboviţa party organization and a PD county councillor.[15] The list of former Securitate officers who benefitted from Băsescu’s political and economic connections goes on.

Despite the connections and shady dealings revealed by the media, it is important to note that many of the political appointments and promotions were facilitated first and foremost by post-communist Romania’s unwillingness to resolutely break with its communist past. Securitate officers continued their careers as part of the SRI because no law prevented them from doing so; by 1989 Băsescu’s acquaintances in the Securitate had the seniority required to head the new intelligence services. In their positions as the leaders of the institutions that inherited the Securitate files, the former Securitate officers could hide documents that incriminated Băsescu and refuse to hand them over to the CNSAS. Interestingly though, the 2019 court case revealed that the CNSAS had received two significant documents from the SRI many years previous. Yet, it never considered them when investigating candidate Băsescu ahead of the various elections. Ironically, this suggests that the SRI was more willing to share information on Băsescu’s past than the CNSAS, although it is the SRI that usually keeps its communist roots a secret while the CNSAS has the mission to publicly disclose that past.

For historian Marius Oprea and journalist Ion Cristoiu, the willingness of the CNSAS to keep the documents hidden for many years and to reveal them publicly in an electoral year showed subordination to former secret agents like Băsescu, abdication from its own mandate of helping the Romanian public identify the former Securitate agents and direct involvement in the 2019 elections.[16] Oprea further focused on the CNSAS Investigation Department, which is responsible for making relevant secret documents available to the CNSAS leadership when an individual’s former past is investigated. Over the last two decades, the Department repeatedly stated that no secret documents implicated Băsescu. However, proof for Băsescu’s willingness to supply information on others could be found in other files because copies of information notes were included both in the file of the informer and in the files of those he spied on. Thus, even if Băsescu’s informer file had been destroyed, proof of his collaboration could still be hidden in the victim files.

Such an extensive search was apparently conducted only in 2019, when the CNSAS found proof that Băsescu did supply the secret police with information on others. In 1979 Băsescu joined the Communist Party and, according to the practice of the time, his file as a Securitate informer was destroyed. However, two of his handwritten notes survived in the secret files of his victims. The notes show that Băsescu informed on fellow students and various foreigners he encountered during his voyages abroad, under the codename Petrov. This version of events was upheld by the Court of Appeal, although Băsescu insisted that he gave information to the military counter-intelligence service, without knowing about the service’s subordination to the Securitate.[17] But codenames were selected by informers in consultation with the Securitate case officer during a recruitment process where informers had to commit to collaborate secretly and truthfully.

The Court of Appeal verdict further raised questions about the impartiality of the CNSAS and the reliability of its investigations. To be sure, sifting through hundreds of thousands of archival records requires institutional capacity, both in financial and personnel terms. Yet few acknowledged this point. Most journalists were eager to present Băsescu as an all-powerful politician who puppeteered the CNSAS, even after his second presidency had ended. The most bizarre allegation linked Băsescu to the 2013 suicide of the CNSAS archivist Iuliana Măgirescu. Shockingly, the news portal Cotidianul claimed that the suicide occurred because Măgirescu discovered documents attesting to Băsescu’s former collaboration.[18]

Public debate went even further to pit Băsescu’s anti-communist friends against his leftist opponents and touch on larger issues regarding how the communist past is remembered and interpreted and how it has impacted the post-communist Romanian democracy and rule of law. The GDS weekly 22 reminded readers that the Court of Appeal verdict was not definitive, featured an opinion piece signed by Mădălin Hodor from the CNSAS which claimed that some of the documents that incriminated Băsescu and appeared in the press when the verdict was made public were in fact false, and published Băsescu’s anti-PSD Facebook comments ahead of the November presidential elections.[19] The willingness of the GDS intellectuals to rally behind Băsescu even after his reputation was severely damaged by the court verdict stemmed from their fear that the PSD could win the 2019 elections “in a country that underwent no real decommunization, but was traumatized for half a century by the ‘good’ inflicted on it by the communism ‘that liberates,’ a country still marred by the legacy of that regime.”[20]

While the GDS saw communism as a criminal regime responsible for more deaths than Nazism, Băsescu’s most prominent critics, namely historians with the Romanian Institute for Recent History, pointed out that the problem rested with Băsescu the person, not the communist regime as a whole. For Cristoiu, the revelations showed once again that the post-communist state institutions have been used and abused by a “parallel state” formed of Securitate agents who, after 1989, recast themselves as democrats.[21] For Stelian Tănase, the revelations showed that communism was beneficial not only for Communist Party leaders but also for technocrats of local importance like Băsescu; in addition, the revelations showed the need for the complete re-evaluation of Băsescu’s presidency, including the reasons why he created the presidential commission.[22] Echoing this position, Bogdan Enache noted that President Băsescu’s overreliance on the security sector to punish selected politicians and state dignitaries engaged in corruption showed not only an enormous trust in his former collaborators in the Securitate but also the weakness of the post-communist state institutions and the rule of law.[23]

This debate, which preoccupied Romanians for the better part of 2019, showed that disagreements about the nature and legacy of the communist past remain relevant thirty years after the collapse of the regime. Political parties, analysts and even ordinary voters remain divided over the meaning of communist-era collaboration; whether it stemmed from patriotism and necessity or denoted a willingness to condone a repressive dictatorship that routinely infringed on basic human rights. Some believe that unveiling former Securitate secret agents is an urgent necessity. For others, the Băsescu case amounted to “a second victory of the Securitate” over Romania, which was unable and unwilling to break with its communist past.[24]

Lavinia Stan: The Băsescu Case: Romania's Lustration Debate Revisited. In: Cultures of History Forum (13.12.2019), DOI: 10.25626/0106.

Copyright (c) 2019 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

Raluca Grosescu · 17.01.2019

The Trials of the Romanian Revolution

Read more

Monica Ciobanu · 19.02.2018

Criminals, Martyrs or Saints? Romania’s Prison Saints Debate Revisited

Read more

Oana-Valentina Suciu · 12.09.2017

'Lex CEU': Romanian Echoes and Trends

Read more

Bogdan C. Iacob · 07.05.2014

Romania - The Scramble for the Present: Making Sense of the Crisis in Ukraine

Read more

Gundel Große · 02.09.2013

Romanian Writers and the Securitate. Excerpts from a Debate

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).