16. May 2017 - DOI 10.25626/0063

Raino Isto is a Ph.D. candidate in art history at the University of Maryland, College Park. His research addresses the relationship between history and memory in socialist-era monumental sculpture, and the ways postsocialist art engages with socialist monumentality. His recent work focuses on producing a theory of postsocialist monumental practice, considering the diverse ways that socialist monumentality has been adopted as a ground for experience in post-1989 Eastern Europe. He has published articles on both East European and Chinese art. He is also a practicing artist, see afterart.org

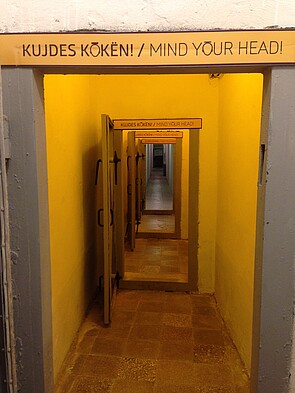

On 22 November 2014 a multi-level underground bunker on the outskirts of Tirana, the Albanian capital city, was opened to the public for the first time. The bunker had originally been constructed in the 1970s, during the country’s socialist period, as part of the widespread transformation of public space and landscape that took place during the 1960s and 1970s, and was intended to house the heads of state in the event of a nuclear attack on the nation.

The bunker’s aggressively publicized reopening as Bunk’Art – a combination museum and art installation space – is one of the most fraught and complex attempts on the part of the Albanian government to come to terms with the nation’s recent history, according to the museum’s website. The space, paradoxically devoted both to the period of fascist occupation in Albania and to the subsequent period of isolationist socialist dictatorship, intertwines a plethora of documents, photographs, and museum installations of questionable historical veracity. Bunk’Art represents a unique confluence of aesthetic discourses, strategies of memory-production, and policies related to architectural heritage and tourism, and the museum offers a particularly poignant example of post-socialist political manoeuvring vis-à-vis the socialist past.

Bunk’Art opened to the public just over a year after the leader of the Albanian Socialist Party, Edi Rama, took office as Prime Minister in 2013.[1] Rama, formerly known for his years as mayor of the capital city during the first decade of this century, and for his insistence on fusing art and politics to transform the Albanian urban landscape, declared on the occasion of Bunk’Art’s inauguration, “Today, we are witnesses because we have opened the door of a treasure of our collective memory.”[2] On Twitter, he later added – in a statement that would prove prophetic in light of the exhibition’s immediate and sustained popularity with both domestic and foreign visitors – “The underground world of the dictatorship will, undoubtedly, turn into a historical, cultural, and touristic attraction.” Not long after its opening, the museum closed, only to later re-open for a new season, close again, and finally re-open – apparently now on a permanent, rather than seasonal basis – in the early summer of 2016.

When Bunk’Art first opened, it contained not only exhibition spaces and panoramas devoted to the German occupation of Albania, the Italian occupation of Albania, the immediate post-war diplomatic situation, and the socialist period, but also a series of artistic installations curated by the owners of Miza Gallery, a small but flourishing contemporary art exhibition space in Tirana. At the time, the inclusion of artistic installations within the space seemed to link Bunk’Art to Edi Rama’s own prior artistic, painterly interventions in Albanian public space,[3] and it is certainly the case that Rama’s government has continued to engage in promoting the creation of (centralized, official) art spaces as part of its project of national modernization.[4] From the beginning, however, Italian media entrepreneur Carlo Bollino was the key figure in shaping the development of Bunk’Art, and Bollino’s vision for its historical eclecticism has become a driving force after the museum re-opened under the guise of what is clearly more of a private entity (rather than the state museum it had first appeared to be).[5]

This essay focuses on Bunk’Art as a paradigmatic case of the recently accelerated ‘making-public’ of socialist spaces in contemporary Albania. It examines the intertwining modes of avant-garde political and artistic practices with neoliberal discourses of international tourism and the explicit project of framing collective memories of the socialist period. Prime Minister Rama’s statement at the inauguration of Bunk’Art, that “we have a project to create a historical and tourist itinerary of the communist underground and simultaneously to turn this itinerary into an itinerary of the creative [imagination – the author], aiming on the one hand [for] the liberation and on the other hand the fertility of our collective memory.”[6] reveals the symbiotic dynamic being constructed between memory and a touristic conception of historical experience.

Perhaps ironically, at a time when history (as represented in textbooks) was literally being rewritten in Albania,[7] the Prime Minister’s statements about Bunk’Art in fact dismissed the potential value of historical expertise in understanding the socialist years. Rama explained, in his speech on the occasion of Bunk’Art’s opening, that he believed “that the writing of history should be left to the historians,” nonetheless, he added:

A visit to this anti-atomic (sic) building will surely tell the girls and boys of this country more about the dictatorship, about Enver Hoxha, about Mehmet Shehu, about all antihuman and anti-religious hordes produced by the so called liberation of the homeland, than all historians gathered together can tell.[8

Thus, Rama called for systems that would produce affective experiences closer to that of the country’s collective enclosure under dictator Enver Hoxha, experiences that would educate new generations of Albanians, not through the presentation of facts, but through creative images and spatial-temporal programs of movement. More recently, Bollino expanded upon this, noting:

Ultimately, Bunk’Art is another means to reveal the secrets of communism, even if it employs the ‘simplicity’ (though of course accompanied by equally exact historical rigor) that has always separated journalistic accounts from those presented by historians. Bunk’Art does not claim to be a museum in the classic sense (and classic museums, which are in crisis throughout the world, we will leave to the academics). Rather, it is a modern video-museal [museum-like video] exhibition, in which history reveals itself in a form that is more appealing, and, where possible, artistic.[9]

My purpose here is to analyse the convergence and divergence of discourses on art and memory in the case of Bunk’Art, considering the simultaneous celebration of artistic intervention and expression and the framing of authentic historical engagement with the Hoxha years as a function of experiencing this past via touristic networks. These shifting narratives cannot be understood without recognizing that current Albanian politics of cultural heritage are explicitly shaping memory as an aesthetic phenomenon, both in the theoretical and in the practical sense. Projects like Bunk’Art rely rhetorically on art installations as much as they do the presence of documents and objects for their impact – they need to appear to foster creative interpretations in order to avoid the accusation that they perpetuate an official and monolithic narrative of the socialist past.

The aesthetic mapping of memory also finds its spatial (and psychoanalytic) corollary in the link between the massive ‘underground’ bunker constructed for the dictator and the thousands of smaller concrete bunkers that dot Albania’s landscape from the time of socialism, when they were constructed so that citizens could ostensibly defend the country against external attacks.[10] This contrast between localized invisibility-made-visible (the collective unconscious of socialist memory) and the dispersion of visual markers of the country’s former isolationist paranoia (the surface element of a grid of mobility and, to put it bluntly, advertising) is developed under the aegis of a politics as both Modernism and modernization. In turn, this modernization is cast as the pure intervention of artistic subjectivity, with Prime Minister Edi Rama’s reputation as statesman-painter used to construct a new model of neoliberal economics, avant-garde aesthetics, and post-socialist politics of commemoration.

It is worth considering the significance of Bunk’Art’s avant-garde tendencies (its apparent refusal of a coherent structure of historical meaning), since it is only through attempting such an analysis that we can approach an understanding of where Bunk’Art situates itself in relation to the curatorial radicalism of earlier avant-garde museum practices, the irony of neo-avant-garde artistic endeavours, and the logic of administration that dominates in the context of the neoliberal culture industry. As we have seen (from the statements given by Prime Minister Edi Rama), Bunk’Art operates not so much according to the logic of counteracting the forces of forgetfulness or the active destruction of heritage, but rather according to the logic of the maximization of resources. For Rama, the issue is not primarily to radicalize the practice of memory or the understanding of history in order to preserve the lessons bequeathed to the present by both trauma and tradition. Instead, Bunk’Art explicitly takes part in ensuring the efficiency of memory production; it makes existing reserves of the socialist past more widely available in order to produce particular effects. Before discussing these effects, let us consider Rama’s lengthy discussion of Bunk’Art’s creative potential:

We are here to open a new phase of relationship with the past, not to rewrite history, but to expose the past in all forms that we have, first of all as an opportunity to place before the eyes of the young generations, but also to everybody else, its evidence, its recesses, its images, its documents. Obviously, as an opportunity to inspire the creative imagination, because without the slightest doubt, the installations that we saw with the authentic rooms of the old regime chiefs are a meaningful evidence of the possibility that this space creates in order to create new spaces: new spaces for imagining, thinking, and living together through the power of art.[11]

The socialist past, here, is already conceived as available – it needs only to be placed fully at the disposal of the Albanian people in order to realize its role as the catalyst for the creation of new aestheticized and aestheticizing spaces.

In other words, rather than specifically aiming at the production of new forms of (collective) memory or new meanings, Bunk’Art is intended to function primarily as the means for a proliferation of spaces, and specifically of inner spaces. That is to say, its function is the production of the spaces traditionally associated with the meaning-giving subject, the spaces of individuality and imagination, and its own aestheticized metaphysics openly rejects (as we shall see below) the idea that collective memory can be founded upon the experiences of such subjects. Furthermore, Bunk’Art represents the alliance of this mnemonic subject-production with the political-cultural institution in the era of neoliberalism: for Rama, the role of politics (in the case of Bunk’Art) is precisely to show the way to neoliberal subject-hood by mobilizing the institutions to maximize the resources of memory through the creation of spaces. Here we have the full collusion of avant-garde aesthetic tactics with institutional strategies of collective memory, the proactive administration of the “relation of anticipation and reconstruction” that characterizes the neo-avant-garde’s dialectic response to the radicalism of earlier periods.[12]

But what, precisely, does it mean for Bunk’Art to occur in a neoliberal context (besides the obvious fact that its emphasis is on the efficiency of the mobilization of memory for creative ends)? And what does it mean that this neoliberal context, and the touristic itinerary it produces, is an international one, rather than simply a national one? In other words, if Bunk’Art seeks to transcend a narrowly nationalist model of collective memory, as Rama suggests, how do the (spaces of the) subjects it intends to produce relate to global issues of identity and memory?

If Bunk’Art seeks to reinvent the vast ‘underworld’ of the dictatorship as the sight of discovery and creative development in the collective memory – and here we may read this underworld as the spatial sign for all possible traumas of the past – how does it confront the simple fact that many Albanians today did not live through the Hoxha years, or remember very little of them? The official rhetoric of Bunk’Art is surprisingly sophisticated about its mnemonic limitations: in his speech at the opening, Rama makes it clear that the ideal viewers of Bunk’Art – which is also to say, the ideal tourists of one’s own past – are not those who remember socialism but the children who do not.[13] Thus, the primary point of Bunk’Art as tourism is not to investigate what practices, sites, or images of memory exist as the experiences of living citizens, but to engineer an experience of the past for future generations, by producing not merely the surface network of territorialization, but also the deep network of memory.

Of course, memory itself is part and parcel of all discourses on space, and it is no surprise that in the months following the opening of Bunk’Art, it has become clear that the exhibit is part of an ambitious attempt to imaginative redraw the border of another entity: the border of Europe. In January of 2015, Bunk’Art was followed by the opening of the next architectural site in the recovery of Albania’s socialist past: the House of Leaves, a museum housed at the site where surveillance and torture were conducted during the socialist years. Rama’s pronouncements at the inauguration of the House of Leaves mirrored his earlier rhetorical framing: “In a few years we will have museumized the entire remaining network of the memory of the dark underworld of the communist dictatorship.”[14] The purpose of this ‘museumization’, however, was more explicitly stated in an article by Falma Fshazi, one of Rama’s speechwriters. Fshazi noted the importance of places such as Bunk’Art and the House of Leaves in Eastern Europe:

All such spaces located in the countries of the former Soviet Bloc have been turned into incredibly important European tourist destinations, because together they form –along with similar spaces in Western Europe – the border that divides the mistakes and failures of the past from the future. Aside from the geographic one, this is clearly the other important border that encompasses and defines the European Union. The House of Leaves will be the next in a series of locations that integrates Albania into the European itinerary of collective memory, liberating Albanian society from the continuation of the logic of self-isolation that the dictatorship produced.[15]

Again, the message is clear: the collective memory of the dictatorship is not present, it must be sought and more than that – it must be produced – in order to ‘liberate’ society. But this production of memory is not simply part of an inwardly-gazing mapping of one’s own history: it is also the necessary opening of memory-as-tourism to Europe.

The notion of a ‘tourist gaze’ first described by sociologist John Urry,[16] is conflated with the ‘European gaze’, and – if the borders of the European Union as the embodiment of a particular collective memory are to extend to include the mnemonic topography of Albania – that gaze cannot find just any memory; it must find the right memory. This gaze must be able to take in, not just the surface and its networks, but the depths as well; its itinerary must pierce representations and descend to the heart of the matter.

Indeed, if Bunk’Art can be characterized as fundamentally neoliberal in its goals and manifestation, it is primarily because of the unique combination of the rhetoric of tourism and the logic of entrepreneurship it employs. It is not just that Bunk’Art is framed first and foremost as a source of economic gain (“a treasure of our collective memory”), but more importantly that it facilitates the production of subjects that are, in turn, focused primarily upon creative production. Furthermore, the cultural capital embodied in Bunk’Art, and thus by extension in the traumatic encounter with the socialist past via practices of memory, works primarily as an investment. Not only does it aim to attract foreign tourists – thus explicitly playing upon the perceived exoticism of Albania’s particularly isolated socialist period – but it also aims to mobilize new generations to create their identities through the imaginative spaces the museum suggests, thereby shifting the focus from a collective (or democratic) mnemonics to an individualized one.

“Not to re-write history but to expose the past in all forms that we have”: this is the language of portfolio diversification, and it functions both at the level of the Albanian administration as a whole and at the level of the individual visitors to Bunk’Art. These visitors, after all, will be the citizens of an Albania, of a Europe, ‘liberated’ from the enclosure of the socialist past. This liberation is not only a political one, but also an economic one, or more specifically one belonging to economized creative productivity. In this sense, the imaginations, thoughts, images, and strategies of artistic co-habitation that Bunk’Art aims to foster are also linked to the strategies of creating the figure that political theorist Wendy Brown terms ‘homo oeconimicus’.[16] Just as the socialist past is presented – by Rama and Bollino’s perceived curatorial interventions – as cultural capital ripe for future investment, so are visitors to Bunk’Art envisioned as nascent human cultural capital. Bunk’Art will provide the opportunity for them to achieve “a direct orientation vis-à-vis the testimonies of the past”, an orientation that will spark “their creative imagination”.[17] In this situation, the Albanian government (and the Ministry of Culture in particular) obviates any role in “the writing of history” and contents itself with a role as the facilitator of suitably removed touristic experiences.

In other words, the government takes its place at the head of what John Urry called the “array of tourist professionals […] who attempt to reproduce ever new objects for the tourist gaze”. As Urry argues, the tourist gaze is “constructed through signs, and tourism involves the collection of signs”.[18] In Bunk’Art, this is taken a step further: the structural goal is not simply the collection of signs but also their dispersal and proliferation, and with them the opening-up of fresh spaces that can serve as both tourist spaces and sites for the entrepreneurial enrichment of the ‘new generations’ of neoliberal subjects.

Bunk’Art clearly wants to be – and needs to be – many things to many people, and in this way it is no different from many recent attempts to grapple with the memory of the socialist period across Southeastern and Central Europe; this no doubt explains both the vagueness and the eclecticism of its fusion of history, memory, and aesthetics. Even within the chaotic discourse and reception associated with its exhibitions, the centrality of a return to the deep layers of an authentic, shared memory is notable. Perhaps most significant in the ongoing negotiation of Bunk’Art’s place in the “historical and touristic itinerary of the communist underground” is its explicit unification under the aegis of the avant-garde artist working in cooperation with the media mogul: part of the path back to Europe, across the boundaries of memory, is to be found in the cooperation of these two figures, who set the stage for history reimagined as an eclectically creative endeavour, framed in the language of neoliberal productivity.

In November 2016, two years after Bunk’Art first opened, Edi Rama, Carlo Bollino, and Interior Affairs Minister Saimir Tahiri presided over the opening of Bunk’Art 2, a second museum devoted (according to Rama) to “the victims of the communist terror”.[19] While space here does not permit a thorough analysis of this second museum,[20] it is worth noting some of its architectural and rhetorical aspects. Bunk’Art 2 is located in the bustling centre of Tirana, inside an underground bunker located near the Ministry of Interior Affairs and apparently originally associated with that government entity. The entrance to Bunk’Art 2, however, is completely artificial: its entrance is marked by a domed concrete bunker that was constructed by the Albanian government in 2015 – but was intended to visually emulate the above-mentioned bunkers that Hoxha ordered built throughout the Albanian territory. Presumably, the bunker was always intended to serve as the entrance to Bunk’Art 2, but its construction was delayed by protests in December 2015, organized by Albania’s oppositional Democratic Party and in remembrance of the 1990 anti-communist student movements in Albania. The protestors set fire to the artificial bunker, and smashed multiple holes into its thin shell – the bunker itself was not even constructed to the same standards that the Hoxha bunkers had been.(See picture)

The damage to the bunker was ultimately left unrepaired before the museum opened, but the dome was supplemented with an equally artificial adjacent guard tower, wrapped in barbed wire, installed nearby. Bunk’Art 2, in a manner similar to the first Bunk’Art, combines artistic installations with eclectic historical materials, but it is perhaps the serial character of the museum that is most significant: Bunk’Art 2 fulfils the logic first put forward by Edi Rama at the opening of the original Bunk’Art, namely to create “an itinerary of the creative imagination”, in other words, no logical historical development, but rather one bunker-museum after another. On the occasion of the museum’s opening, Interior Minister Tahiri stated, “[Bunk’Art 2] is certainly a matter of art, undoubtedly a matter of tourism, [as well as] a promotion of history and a confrontation with our own past”.[21] The real task facing Albania today is to successfully and critically disentangle what has become so entangled: the strands of art, tourism, the creation of history, and the work of understanding the past.

Raino Isto: “An Itinerary of the Creative Imagination”: Bunk’Art and the Politics of Art and Tourism in Remembering Albania’s Socialist Past. In: Cultures of History Forum (16.05.2017), DOI: 10.25626/0063.

Copyright (c) 2017 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

See the official website of the Bunk'Art museum

A video of the museum opening and full speeches by both PM Edi Rama and Minister of Culture Mirela Kumbaro (in Albanian) on 22 November 2014.

Idrit Idrizi · 27.04.2021

Debates About the Communist Past as Personal Feuds: The Long Shadow of the Hoxha Regime in Albania

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).