11. Mar 2015 - DOI 10.25626/0030

Dr Iryna Kashtalian is the coordinator of the online Belarusian Oral History Archive (www.nashapamiac.org) and the author of many articles on the recent history of Belarus, oral and everyday history and the history of political repression. She completed her PhD at the Free University of Berlin in 2012 and has worked on a number of social and scientific projects for non-governmental organizations.

This article examines modern efforts in Belarus to preserve the memory of the Armia Krajowa (the Polish Home Army), an underground organisation of the Second World War which also operated in areas that had been incorporated into the USSR in September 1939. The content of this article will be of interest to professional and amateur historians seeking to learn more about the practice of memorialisation in areas which were formerly part of the Second Polish Republic. Particular emphasis is placed on analysing how the stance taken by the current political regime has influenced the situation.

The issue of preserving historical memories is always directly connected with the political situation in the country concerned. Current efforts to preserve the history of the Armia Krajowa are no exception and have been prompted by the actions of the country's political regime. Since the very beginning of President Aljaksandr Lukashenka's dictatorship of Belarus over 20 years ago, the official approach to Belarusian history has been to force-feed the public with images of a happy and heroic Soviet past. Accordingly, the state's hired ideologists have actively been keeping those who tell a different story out of school textbooks and official publications. The Polish anti-Soviet underground, a complex and contentious aspect of 20th-century Belarusian history, is one example: it is, for the most part, mentioned only in talks by academics and by the opposition.

"Everyone has the right to remembrance", Mieczysław Jaśkiewicz, head of the unofficial Union of Poles in Belarus (ZPB) and a member of the movement seeking to memorialise the Armia Krajowa (AK), told the Belarusian news agency BelaPAN in 2013.[1] The ZPB is the largest Polish organisation in Belarus: by 2005, it listed 75 registered grassroots organisations, 17 Polish Centres and 25 000 Polish members. In 2005 it was divided by the Belarusian government into an oppositionist branch led by Jaśkiewicz, not recognised by the authorities), and a pro-government branch, headed by Mieczysław Łysy, which is not recognised in Poland. Both organisations have the same name. This situation has had a negative impact on both Polish-Belarusian intergovernmental relations and solidarity within the Polish minority in Belarus. Tensions between the two countries have been further exacerbated by the introduction of the Karta Polaka ('Polish Card'), which grants its holder certain privileges in Poland and facilitates the visa application process. The unofficial branch of the ZPB, supported by Poland, has fought to retain the original organisation's assets. Combined with everything the organisation does that runs counter to the official Belarusian ideology, this has led to ongoing conflict between the ZPB and the authorities. Members of the organisation who are particularly active have found themselves targets of repression. For obvious reasons, the ZPB is frequently covered by the Polish media, and Polish diplomats have expressed their support. Since 2005, the oppositionist ZPB has been actively working to memorialise the AK. The first AK veterans' meeting took place as early as September 1993, under the aegis of the ZPB.

The ZPB is virtually the only group in Belarus trying to preserve the memory of the Polish underground that operated during the Second World War in areas including those which, before becoming part of the Belorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR), had been known as the 'Eastern Borderlands' (Kresy Wschodnie).[2] The AK was a key organisation in the Polish resistance, made up of underground military groups whose aim was to restore the Second Polish Republic with its 1939 borders.

Unlike people in neighbouring Poland, where members of the AK are regarded as heroes, Belarusians have conflicting views on the organisation. Its members are not officially recognised as veterans,[3] and obstacles are placed in the way of their receiving support from the Polish government.[4] Belarusians, who make up the majority of the population, are hardly likely to support the memorialisation of militarised groups that were fighting to return western Belarus to Poland, of which it had formed part until 1939. After all, Belarusian nationalist movements had been nipped in the bud in precisely those areas, when Józef Piłsudski introduced his policy of Polonisation. The official rehabilitation of the AK would prompt discussion as to whether or not it acted justly and would call into question not only the lawfulness of certain acts by the Soviet authorities, in September 1939 and after the liberation of the area from the Germans, but also the legality of territorial claims by the neighbouring country. There is evidence to suggest that AK soldiers committed crimes against Belarusian nationalists and peaceful civilians.[5]

The AK is significant not only to the Polish minority by virtue of having fought the Germans and the Communists for a free Poland; it also arouses interest among those who see it as part of the shared history of Belarus and Poland. It has been noted that the AK numbered both Poles and Belarusians among its ranks. Those who became Soviet citizens for the first time on 17 September 1939 could no longer enjoy the standard of living they were accustomed to, were deprived of their property and suffered repression at the hands of the new regime: inevitably, this group regrets that the AK's fight to return western Belarus to Poland was unsuccessful.

Although discussion of the AK's history is not strictly forbidden, it rarely comes up in public discourse. It is seen as relevant only to the Polish minority, who make up less than 3% of the population. The problem is that any such discussion involves demythologising the history of the USSR. Given the Belarusian government's view that Soviet ideals should be reverentially preserved, official discussion almost never touches on subjects that challenge this thinking. Examples include reports of crimes committed by the Communist dictatorship against the Belarusian people, resistance against the Soviet authorities, or the repression of dissidents. The AK is undoubtedly another such topic.

In the search for positive examples, official ideology focuses on Belarusian partisans, victors in the 'Great Patriotic War'. There is no room for objectivity in assessing the actions of the Soviet leadership at the beginning of the Second World War, and members of the anti-Soviet underground are presented as bandits and terrorists. Another problem is that the Belarusian government is, to a certain extent, reproducing Soviet behaviour and supports a policy of Russification, which limits the scope for a multinational approach.

Unfortunately, any kind of multilateral examination of the Soviet period is left entirely to independent historians. Unsurprisingly, they are few in number, since they are threatened with repression of the freedom to express their views and can find themselves excluded from the profession, whether through dismissal or by being prevented from publishing their work or submitting their doctoral theses. Their research is disseminated only by a small group of interested parties, mostly from the community of those opposed to Lukashenka's regime.

Most young people associate patriotism with the old BSSR flag, under which the world was divided into 'us' and 'them'. According to this view of the world, the AK is more 'them' than 'us', given that it called for the reinstatement of the situation as it had been under the terms of the 1921 Treaty of Riga, which divided Belarus between two countries. Most Belarusians have little access to objective information and therefore have a stereotyped perception of the AK that dates back to Soviet times: 'bandits', Belopolyaki or 'White' Poles (a term used to designate enemies of the Soviet state), collaborators, murderers of Belarusians… Under the influence of the government stance, even those who were alive in western Belarus at the time unthinkingly repeat the official line on the events of 1939: that they were liberated from their Polish overlords, and they brand members of the anti-Soviet resistance 'bandits' and 'shoplifters'.

Examining eyewitness accounts reveals quite clearly that those Belarusians who took a milder, more objective view had been in direct contact with members of the organisation and were therefore less inclined to demonise them. They described members of the AK as local people who considered themselves Polish[6] or who had been sent over in the period of Polish rule[7] and believed that Poland would return to how it had been.[8] The eyewitnesses themselves sympathised with, although did not always support, this belief.

Although some books examining the activities of the AK have been published in Belarus, they are few and far between. The most significant include research published in the 1990s by the public commentator Yaǔhen Siamaška[9] and by the historians Viktar Jermalovič and Siargej Žumar[10], and a monograph on the anti-Soviet underground in the BSSR in the period 1944-1953 by Ihar Valachanovič, who – thanks to the nature of his work – had special access to the KGB archives.[11] They offer not only factual information, but also documents and fragments taken from the memoirs of witnesses. The activities of the AK have been investigated much more extensively by Polish researchers, most recently Grzegorz Motyka[12] and Zygmunt Boradyn.[13]

The Polish anti-Soviet underground started operating in areas of western Belarus too, after these had been incorporated into the BSSR in autumn 1939. Similar organisations existed in Poland itself. During the War, the underground was reorganised to form the AK, a clandestine military organisation which divided the territory of the former Second Republic into administrative areas (obszary) under commandants who represented the Polish government in exile in London. These administrative areas were further split into districts (okręgi). Belarus included the districts of Navahrudak (the biggest), Vilnius and Polesia, which together made up the Białystok Obszar.[14]

Before 1943, Soviet and Polish underground organisations operated side by side without hindrance to one another. In June of that year, however, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Belarus issued a decree on "Further development of partisan activity in the western regions of Belarus" and a secret letter entitled "Military and political tasks in the western regions of Belarus". Both decreed that only armed groups acting in the interests of the USSR were lawful. From then on, the Soviet side began to confront the Polish organisation with the aim of weakening it and ultimately causing it to collapse.

According to data analysed by Ihar Valachanovič, by the time the BSSR was liberated from the Germans there were more than 35 000 active members of the various collaborationist organisations operating in the area, alongside approximately 250 German intelligence and counter-intelligence stations, some 20 000 members of the AK, more than 12 000 members of the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists/Ukrainian Insurgent Army (OUN-UPA) and approximately 1000 members of the Lithuanian anti-Soviet underground.[15]

All the anti-Soviet underground organisations resembled each other in that they had a similar hierarchical internal structure, answered to various émigré centres and shared one key aim – to change the political and governmental structure of the BSSR. Their methods included anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda, sabotage of Soviet-led actions, armed uprisings, diversionary tactics and acts of terrorism. The degree of organised resistance was the key factor which set underground organisations apart from spontaneous protests carried out by individuals or groups in response to a particular event. The AK evidently came to represent the interests of a significant part of the population of western Belarus, as it had more influence in this area than anywhere else.

The first phase of the AK's post-war activities in Belarus lasted from July 1944 to January/February 1945. The organisation was officially disbanded on 19 January 1945, when it became clear that, in the increasingly complex international context, it was fighting in vain: the USA ceased to recognise the Polish Government-in-Exile and the UK offered a legal justification for the USSR's liquidation of AK structures, thus influencing international opinion. Many commanding officers ignored the order to disband, although the Polish resistance was significantly weakened by the legal and illegal emigration of a significant number of AK members during the population exchange with Poland and by the conviction of its senior leaders at a show trial in Moscow (the Trial of the Sixteen –18 to 21 June 1945).[16] The AK then entered the second phase of its existence, during which its stated objective, in response to its abolition by repressive state authorities, was to turn to terrorism to fight the Soviets.

During the post-war period of AK activity on liberated Belarusian territory, the repressive Soviet authorities, supported by sections of internal forces and of the army, carried out large-scale military‑security operations which significantly weakened AK activity. From 1945 to 1948, the most active AK resistance was carried on in the Hrodna, Vaŭkavysk, Lida and Ščučyn regions by locals and also by members of the AK who had been unable or unwilling to move to Poland at the time of the 1944-1946 population exchange.[17]

Repression was the most important factor in wiping out the AK's organised resistance. Despite its gradual liquidation, however, the AK went a long way towards destabilising domestic politics and was perceived by the security forces as a serious threat to the existence of Soviet power in the area.

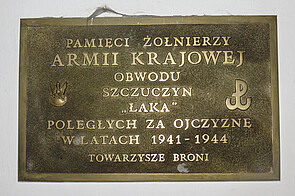

Not unnaturally, the majority of those who had hoped that Poland would reclaim its pre-1939 territories moved away in the population transfer of 1944-1946. The AK lost most of its support in what are now the territories of Belarus, and its concept of historical justice became nothing more than an unrealised utopia with nobody around to support it. Today, the memory of the AK is preserved mostly by the Polish national minority, largely resident in the Hrodna Voblast. Most of the better known memorials linked to AK activity are in this region.[18] In general, they can be found as memorials in Catholic graveyards or as plaques in churches, often installed on the initiative of former AK members.[19] Here are just a few:[20]

Vavjorka, Lida Raion, Hrodna Voblast. In the graveyard is the resting place of an AK soldier from the 'Ponury' division. 'Ponury' himself, Jan Piwnik, was buried there before his ashes were moved to Puszcza Świętokryska;

Dzeraǔnaya, Staǔbtsy Raion, Minsk Voblast. In the graveyard by the Church of St Peter and St Paul, there is a cross in memory of the AK soldiers who fought in Naliboki Forest;

Iǔje, Hrodna Voblast. On a wall inside the Church of St Peter and St Paul, there is a memorial plaque dedicated to the soldiers of the 4th Battalion of the 77th Infantry Regiment of the AK who died fighting the Germans;

Laǔžy, Ašmiany Raion, Hrodna Voblast: a chapel in memory of the village of Laǔžy (Polish: Ławże) and the AK soldiers who perished there (23 February 1945). In 1993, following a decision by the Ašmiany district authorities and on the initiative of the village’s former inhabitants, a modest metal cross was erected. On it, a plaque in Belarusian described the fate of the village and its inhabitants. On 23 July 1995, the cross was replaced by a small brick chapel, built by the Polish community and former inhabitants who had migrated to Poland after 1945. The design is by architect G. Maškievič;

Narač, Miadziel Raion, Minsk Voblast. In 1992 In 1992, a sentinel cross was erected over the Polish graves near the Church of St Andrew in memory of partisans from the AK's 'Kmicic' unit who were treacherously killed by the Soviet authorities;

Necieč, Lida Raion, Hrodna Voblast: two memorials. A graveyard memorial, built in the 1990s, to the soldiers of the 1st and 4th divisions of the 77th infantry regiment of the AK who died for Poland in and around Navahrudak between 1941 and 1945. There is also a memorial plaque in the Church of St Michael the Archangel dedicated to the soldiers of the 4th battalion 'Ragner' of the 77th infantry regiment of the AK and inhabitants of the Lida region who died, were killed, disappeared or perished in prisons and camps while fighting against the Nazis and Stalin's regime;

Navahrudak, Hrodna Voblast. Church of the Transfiguration: plaque in memory of soldiers from the Navahrudak division of the AK who were killed in the war;

Ašmiany, Hrodna Voblast. Church of St Michael the Archangel: epitaph to the soldiers of the 8th (or 'Tura') brigade and 'Jarema' unit of the AK, and to the victims of political repression. It was placed there on 18 October 1992 by the Catholic parish and Poles living in the city.

Soly, Smarhoń Raion, Hrodna Voblast. Church of Our Lady of the Rosary: epitaph to soldiers of the 9th Ašmiany Brigade of the AK who died in battle or were killed in camps;

Surkonty, Voranava Raion, Hrodna Voblast. A memorial installed on 8 September 1991 to the soldiers of the AK Okręgi 'Now' and 'Wiano' who died near Surkonty on 21 August 1944 and in the region of Dubičiai on 19 August 1944;

Ščučyn, Hrodna Voblast. Two memorials: a 1992 church memorial plaque dedicated to soldiers of the Ščučyn division 'Łąnka' who died for their fatherland between 1941 and 1944 and a graveyard memorial to AK soldiers who died "For the freedom of the Ščučyn lands" on 29 April 1944 (with names).

The list could go on. Many memorials which have been created in remembrance of loved ones are not known to the public.[21] The apparent concealment of this information could be put down to a desire to avoid problems with the authorities. One instance of negative consequences was the experience of those who, in May 2013, planted a cross on the spot where one of the AK's leaders, Anatol Radziwonik (pseudonym 'Olech'), is supposed to have died.[22] Ščučyn Court ordered ZBP leader Mieczysław Jaśkiewicz and AK veteran Weronika Sebastianowicz to pay a fine under Article 23(34) of the Code of Administrative Offences of the Republic of Belarus (which covers "unsanctioned mass meetings").[23] The Polish minority supported the accused: even though only a few people were present at the erection of the cross, more than 50 members of the ZPB came to the court hearing as a sign of solidarity.

2013 was declared "Year of Remembrance for AK soldiers" in Poland. The Polish minority in Belarus took this initiative very seriously: they built memorials and organised visits to landmarks important to the memory of the AK, and information about the AK was added to the War exhibition at Hrodna State Museum of History and Archaeology.[24] Only time will tell whether the fight to preserve the memory of Poles in Belarus will continue to be successful and systematic. The Białystok branch of the Institute of National Remembrance issued a 2014 calendar entitled "Soldiers of the Polish underground" ("Żołnierze Polski Podziemnej")[25] which featured portraits of AK leaders from the Vilnius and Nawahrudak Okręgi. 1 March is marked in the calendar as "Narodowy Dzień Pamięci Żołnierzy Wyklętych" (National Day of Remembrance for the 'Doomed Soldiers', introduced in 2011) to remember soldiers of the armed anti-Soviet and anti-Communist underground of the 1940s and 1950s; the date is also observed by the ZBP.

In summary, memorialisation of the AK in Belarus is promoted exclusively by the Polish minority. What is more, most Belarusians know very little about it, since the unofficial ZPB is unable to spread information on a wide scale. Attempts to draw public attention to newly built AK memorials with the help of its veterans can lead to confrontation with the Belarusian authorities and ultimately fines or damage to the memorials. The Belarusian officials' response largely depends on the current state of relations between Poland and Minsk.

Most Belarusians tend to pay little attention to the memorialisation of the AK not so much as a result of the lack of information, but rather because there is little interest among those who do not consider themselves Polish or residents of the western regions of Belarus, and because people are unwilling to 'get involved in politics', as this could lead to avoid confrontation with the authorities. Others fear that the memorialisation of the AK could shift Belarus's geopolitical emphasis towards the West. Under the influence of Russia and its calls to "save Orthodoxy", some may see Poles as enemies. They do not want to accept that Belarus’s history brought together people of many different ethnicities and cultures – and that it owes its richness to this amalgamation.

Translated by Catriona Gillham

Iryna Kashtalian: Strangers at Home: Memorialisation of the Armia Krajowa in Belarus. In: Cultures of History Forum (11.03.2015), DOI: 10.25626/0030.

Copyright (c) 2015 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

Nelly Bekus · 16.02.2021

Historical Memory and Symbolism in the Belarusian Protests

Read more

Nelly Bekus · 27.09.2019

Between a National and a Global Mnemonic Agenda: Memory Activism Around the Kurapaty Memorial Site i...

Read more

Aliaksei Lastouski · 07.05.2014

Belarus - In the Tight Embrace of the 'Russian World': Belarusian Reactions to Events in Ukraine

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).