15. Sep 2015 - DOI 10.25626/0043

Ljubinka Petrović-Ziemer is a professor of German literature and cultural history at the German Studies Department of the Philosophical Faculty in Sarajevo. In the area of literature and cultural studies, her focus of research includes contemporary drama and theater, as well as gender and body studies. Her second area of interest is peace and conflict studies, where her focus is on integrative cultures of remembrance and coming to terms with the past in postwar societies, as well as theories of conflict transformation.

In history books, travel guides and the international public sphere, Sarajevo is basically linked with three historical events. On 28 June 1914, Gavrilo Princip, a member of the nationalist revolutionary movement Mlada Bosna (‘Young Bosnia’), assassinated the heir to the Austrian throne Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Duchess Sophie Chotek, an event which is generally considered to have triggered the First World War. The ‘Sarajevo 1878–1918’ museum, located near the site of the assassination, is nowadays the most prominent site of remembrance of the killing, the Archduke and Duchess, and the Young Bosnian movement. The second, more pleasant event was the 14th Winter Olympics held in Sarajevo in 1984. The Siege of Sarajevo during the Bosnian War of 1992 to 1995 is the third historical event generally associated with this city. The extent of devastation caused by war and violence is still evident today in the many bullet holes and ruins, including some of the Olympic facilities. Sarajevo’s tension-laden historical culture, in particular with reference to the war of the 1990s, is the focus of this article. Some historical background information on the city’s political divisions will be provided by way of an introduction. An overview of the development and implementation of initiatives for cultural remembrance will follow, with a closer look at the permanent exhibition on the Siege of Sarajevo at the Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina as well as the permanent exhibition at the ‘Srebrenica 11/07/95’ gallery. Finally, a number of blind spots and points of contention will be discussed with regard to official cultures of remembrance in Sarajevo.

Sarajevo is the capital and seat of government of Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), of the Bosniak-Croat Federation of BiH (FBiH), and of the Canton of Sarajevo. According to the constitution of Republika Srpska (RS), Sarajevo is also the capital of the Serbian entity, even though since 1998 Banja Luka has been the seat of government. The spa town Pale, not far from Sarajevo, had previously been the political center of the RS.

Prior to the war, Sarajevo was a unified city. After the war, it was divided into two administrative districts by the Inter-Entity Boundary Line, established by the Dayton Accords in 1995. The federal part of Sarajevo consists of four municipalities: the Old Town (Stari Grad), the Center (Centar), the New Town (Novi Grad) and New Sarajevo (Novo Sarajevo). The area belonging to the RS is referred to as East Sarajevo (Istočno Sarajevo). It is made up of six municipalities and is located in southeast Sarajevo. The federal part of Sarajevo is primarily urban in character, whereas East Sarajevo is largely suburban and rural. The population is ethnically heterogeneous in federal Sarajevo, although Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims) clearly comprise the majority. The Serbian part of the capital is almost exclusively inhabited by Serbs. The geographical division of the city corresponds to a political one. The most obvious reflection of the political-administrative division of the city is the fact that both parts of Sarajevo have their own independent government corresponding to their affiliation with one of the two entities. The need for cooperation and mutual exchange is therefore greatly limited. The divide is further exacerbated by mutually conflicting narratives and interpretations of the armed conflict and siege. The effects these dichotomies have on each side’s respective historical cultures will be examined in more detail in the following.

According to the UN war crimes tribunal, at least 15,309 people, 4,015 of them civilians, were killed during the 1,425-day siege of Sarajevo from April 1992 to December 1995.[1] "Serbian forces closed a tight ring around Sarajevo which lasted until the end of the war, that is to say 44 torturous months. From the surrounding hills, they constantly bombarded the city with mortars – some days up to 500 times an hour. [...] Sheer survival became an entire city’s primary objective."[2] For these war crimes against the civilian population, the UN war crimes tribunal has to date sentenced the former commanders of the Sarajevo Romanija Corps of the army of the Republika Srpska (Vojska Republike Srpske), Stanislav Galić[3] and Dragomir Milošević,[4] as well as the former chief of staff of the Yugoslav People’s Army, Momčilo Perišić,[5] who has meanwhile been acquitted. Though court decisions are undoubtedly an important aspect of the judicial and social reappraisal of past crimes, they can sometimes deepen the divide between formerly warring nations if the verdicts do not find broad acceptance among the population, as has been the case in Bosnia and Herzegovina. At present, Bosnian society is far from reaching any kind of minimum consensus on the nature of the war and the exact order of events. The mere question of when the war in Sarajevo began can provoke the most heated polemics and cause old traumas to resurface. It leaves not only a superabundance of information and interpretations that scarcely fit together, but also the feeling of being controlled by a past that is more formidable than life itself.

Serbian historians and politicians date the outbreak of the war in Sarajevo to 1 March 1992 when, during a wedding procession in the Old Town, Nikola Gardović, the father of the groom, was shot down outside the old Orthodox church and Radenko Miković, the presiding priest, was wounded. The bride and groom have since been raised to iconic status by the Serbian community, becoming an integral part of a supposedly centuries-long history of Serbian suffering. What this narrative of victimhood fails to take into account is that the years-long siege of the city can hardly be justified as payback for a single crime. The murder of the wedding guest was committed by Ramiz Delalić, a member of the Bosniak paramilitary unit "Zelene beretke". His promotion to commander of the 9th Mountain Brigade of the Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Armija Republike Bosne i Hercegovine) at the start of the war outraged the Serbian populace of Sarajevo.

In the collective memory of federal Sarajevo, on the other hand, the crime receives no mention. The outbreak of the war is dated to 5 April 1992, when Muslim medical student Suada Dilberović (24) and Bosnian Croat Olga Sučić (34) were killed by Serbian snipers during a peace protest. The city was surrounded by Serbian forces the very next day and would be under artillery and mortar fire until the end of the war. In the official historiography of federal Sarajevo, April 6th marks the beginning of "aggression by the Serbian-Montenegrin Army against BiH",[6] with Suada Dilberović and Olga Sučić being cited as the first victims of the Siege of Sarajevo.

Yet even before the first fatalities in Sarajevo, important decisions had been made at the macropolitical level regarding the future of BiH, the effects of which only exacerbated an already tense political situation. Alarmed by Serbian brutality in the war of independence in neighboring Croatia, Muslim and Croatian representatives in the government of BiH decided in October 1991 to override Serbian objections at the European Economic Community and apply for recognition of BiH as an independent state, whereas representatives of Bosnian Serbs endeavored to form an independent Serbian state that openly sought to merge with the now Serb-dominated remainder of Yugoslavia. The request for Bosnian independence was submitted on 24 December 1991, whereas the founding of Republika Srpska was declared on 9 January 1992. Hence, in the overall political context, the murders of Nikola Gardović, Suada Dilberović and Olga Sučić occurred between the referendum for Bosnian independence, which was held between 29 February and 1 March 1992 and boycotted by the Serbian majority, and the recognition of BiH as an independent state by the European Economic Community and the United States on 6 April 1992.

Typical of the divided cultures of memory in Sarajevo and throughout Bosnia is a tendency to not even mention the victims of other ethnic groups. Only the victims in one’s own ranks and the crimes of enemy troops are remembered. There are currently three official designations for referring to the war. The Croatian interpretation of the conflict refers to it as the Homeland War; the Bosniaks consistently speak of Serbian or Serbian-Montenegrin aggression and the defensive war of the Bosnian army; and Serbian historians refer to it either as a civil war or a patriotic war. Ethnic-nationalist historical works generally do not point out these differences in interpretation.

The official politics of memory in the federal part of Sarajevo focuses on the suffering of an ethnically relatively mixed civilian population that was under constant fire during nearly four years of siege and that fought collectively for their very survival. Though the besieged city of Sarajevo had a predominantly Bosniak population, it was nonetheless considered a multicultural haven of BiH even during the war. In the city’s war narrative, the Serbian besiegers were pitted against a collective of victims specifically defining itself as multiethnic as opposed to monoethnic. It was not the Bosnian Muslim community that was being targeted for destruction in the eyes of the besieged; it was the city of Sarajevo as a symbol of urban, multicultural coexistence.

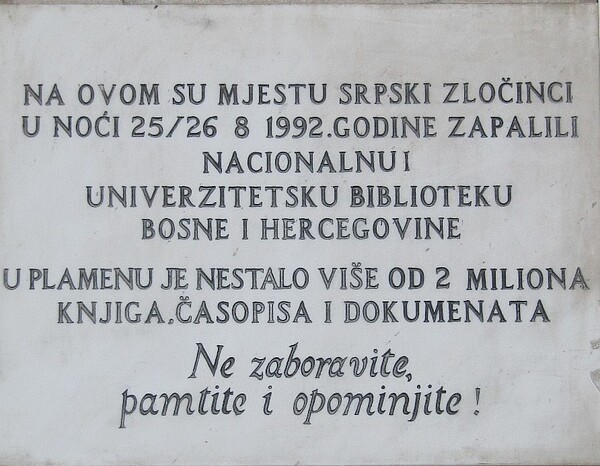

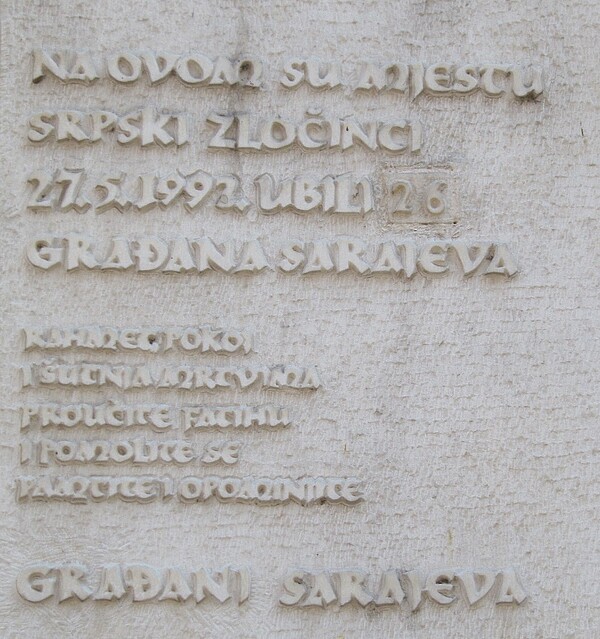

The first initiatives for cultural remembrance were implemented immediately after the war.[7] Bomb craters on the streets and sidewalks of Sarajevo were filled with red resin as a reminder of those killed there by falling mortar shells. Impacting shells had left holes in the form of roses, hence the name 'Sarajevo roses' given to these places of memory. Memorial plaques and walls, public monuments, as well as war graves and cemeteries are other ways the city has commemorated the death of civilians and members of the Bosnian armed forces. The commemorative plaques are put on buildings, public institutions, factories and large enterprises, and serve to memorialise the individuals killed by enemy fire outside or inside the respective buildings. In terms of information, the plaques contain the date of the attack and the number of victims, as well as a collective designation for the perpetrators. Rarely does the perpetrator go unnamed. Especially in the case of schools, it is common for each pupil and teacher killed to receive their own plaque bearing their full name on the outer wall of the school building. According to a statistic by the cantonal office for development planning, a total of 106 plaques and monuments commemorating the civil and military casualties of Sarajevo were put in place between 1996 and 2013. Some 80 additional plaques and monuments are planned.[8]The total number of monuments and commemorative plaques in Sarajevo referring to key events and individuals of the twentieth century, by contrast, is 443.

One of the most well-known and frequently visited monuments commemorating the trauma of the last war is the monument to the 1,601[9] murdered children of Sarajevo. In 2006, the government of the canton of Sarajevo approved plans for a large-scale commemorative project entitled "Opsada i odbrana Sarajeva 1992–1995" (Siege and Resistance in Sarajevo, 1992–1996). The project was developed by the cantonal Ministry for War Veterans with the aim of systematically and permanently embedding the experiences of siege, resistance, violence, suffering and death in the collective memory of the capital. The project incorporates planned or as yet incomplete projects of cultural and historical remembrance. It comprises ten sub-projects.[10]

In early 2015, the government of the canton of Sarajevo approved plans to found a museum dedicated to the siege. The museum’s conceptual design is based on the objectives and modules outlined by the virtual "Siege of Sarajevo" museum already in existence.[11] Since one of the key objectives of the project sponsors is to combine memorialisation and learning processes, museum and educational aspects are to closely complement each other throughout the project.

The city’s offerings in terms of historical and memorial culture are broadened by a series of art projects, such as theater and film productions as well as exhibits. The still active Sarajevo War Theater (SARTR) organizes annual theater productions and performances to commemorate the genocide in Srebrenica and the closing of the Omarska, Trnopolje and Keraterm camps near Prijedor. The Bosnian capital Sarajevo endeavours not only to preserve its own history of suffering and survival, but also to create a space for presenting the experience of victimhood in other areas of the country; though admittedly the wartime experiences of the Bosniak community receive much more attention than those of the other national communities. In this regard, two permanent exhibitions are of particular importance for preserving the collective memory, both of which I will examine in more detail below: the exhibit on the Siege of Sarajevo (Opkoljeno Sarajevo) in the Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the exhibit on the genocide of Srebrenica at the "Srebrenica 11/07/95" gallery in the center of town.

This exhibit has two parts. The initial, introductory space describes the aim of the exhibition. This is followed by a very brief and – due to space limitations – rather fragmentary historical overview of the course of political events in Bosnia and Herzegovina, starting with the dissolution of Yugoslavia and its consequences for BiH. The introductory area focuses on two parallel developments: the events leading up to Bosnia’s declaration of independence and those leading up to the founding of Republika Srpska. These historical facts are supported by a selection of official documents, the minutes of parliamentary meetings, newspaper articles and photographs. A further focus in the first section is the creation of the three subsequently warring armies. The outbreak of the war is documented with photo materials and newspaper reports on the peace demonstrations in Sarajevo and the death of Suada Dilberović and Olga Sučić, "the first victims of the Siege of Sarajevo",[12]as well as the official declaration of war. This section of this exhibit closes with newspaper reports and photographs of the peace negotiations with UN representatives and local politicians in besieged Sarajevo.

At this point I would like to point out a contradiction in the introductory area of the exhibit. The first information board explains the exhibit’s objective. It emphasises that the exhibition is intended as a "living museum". In order to give this impression, the exhibitors have relied on empirical material from official documents, decrees, newspaper reports, meeting minutes, election results, etc. What’s more, the exhibit displays original objects. The introductory text presupposes that the exhibit will awaken memories of the suffering experienced by survivors of the siege. Visitors who did not experience the siege will be confronted with the "black hole of civilisation at the end of the twentieth century"[13] and the "endangered human being per se".[14]The introduction to the exhibit stresses that efforts were made to avoid judgments, opinions, and conclusions about the events and experiences of war portrayed. This intention, however, is abandoned on the second information board, which begins the historical overview. The cause given for the "aggression against Bosnia and Herzegovina"[15]is the "dream of Greater Serbia"[16] held out to Bosnian Serbs by Serbian politicians and nationalist intellectuals as an answer to the political and social challenges of the day. The breakup of Yugoslavia and the wars of the 1990s are interpreted as a "conflict between totalitarianism and democracy".[17]

The decision to classify the war as an act of aggression given the fact that there are at least three ways of referring to it in BiH, all of which are fiercely debated, ideally should have been explained to avoid appearing biased right at the start of the exhibit. Another, perhaps more appropriate option would have been to contrast the various definitions of war without any further comment. As it is, dividing the political forces of the former Yugoslavia in its phase of dissolution into a totalitarian Serbian bloc and a non-Serbian democratic remainder is an extreme simplification of a complex political situation.

The second part of the exhibit is divided into several thematic units. The individual sections of the exhibit document the systematic destruction of the infrastructure and economy. They provide representative examples of the effects of military terror on the everyday and working lives of the population. Yet the exhibit also testifies to the impressive creativity, spirit of resistance and humour of the city’s inhabitants, who for years were degraded as the target of a brutal, militarised violence.

The Srebrenica 11/07/95 gallery was opened in July 2012 with the financial assistance of the Turkish Society for International Cooperation. The idea for a gallery dedicated to the genocide victims of Srebrenica came from Tarik Samarah, a photographer living and working in Sarajevo. His black-and-white photographs are the bedrock of the permanent exhibition on the genocide of Srebrenica. In front of the entrance to the exhibition room, visitors are greeted by a black glass wall listing the names and years of birth of the 8,536 victims of Srebrenica. The front part of the exhibition room contains photo portraits of a number of the victims, with no personal information. The same area has computers that visitors can use to access detailed information about the chronology of the genocide, as well as reading eye-witness reports and biographies of survivors. The integrated ‘Mapping Genocide’ tool was developed by the Youth Initiative for Human Rights in Sarajevo. The front room continues with rows of photographs of the massacred as well as their surviving family members. There is a photo reportage about life after the atrocity, including the traumatising search for the missing, the process of mourning and grieving, the onerous existence of refugees, fatherless childhoods and yearly commemorative ceremonies in which the corpses of newly identified victims are given their final resting place. The centre of the room contains a monitor showing two short films. The first film is about Srebrenica, the second is a documentation by Paul Lowe about the Siege of Sarajevo. The monitor is surrounded by photos of graffiti from Srebrenica: public commentaries by UNPROFOR soldiers, disparaging and highly insulting, about the inhabitants of the former UN protection zone. The last part of the room is reserved for temporary exhibits dealing with violence and human-rights violations in present-day wartime and post-war societies. The current exhibit deals with the situation in Syria. This material about Srebrenica transports the visitor to a morbid past and subjects the viewer to feelings of powerlessness and resignation – an emotional state that survivors probably have to cope with daily. The temporary exhibit endeavours to show the continuity of violence and the suffering it causes, while at the same time serving as a bridge from the past to the present.

A point of contention not yet resolved between the Serbian community and the federal city government are labels, on commemorative plaques in particular, suggesting the collective guilt of the Serbs. As mentioned above, commemorative plaques in public places serve as a reminder of the fatalities caused by the siege, often mentioning the victims by name and ascribing a collective guilt to the perpetrators ('srpski zločinci', or Serbian criminals). Inscriptions like these tend to collectivise guilt and criminalise an entire ethnic group. Such public practices of cultural remembrance essentially reverse the process of individualising guilt accomplished primarily through the criminal prosecution of war criminals. Thus, commemorative plaques of this sort acquire the status of enduring public documents with a dual function: remembering and accusing. The publicly inscribed collective guilt of the Serbs has negative effects not only on the efforts to rebuild trust between formerly hostile camps; it also has a divisive effect on school children and the younger generation.[18] There is no indication that these practices will change anytime soon.

Crimes committed by members of the Bosnian army against the non-Bosniak population, especially members of the Serbian community, are a blind spot wholly ignored in the public discourse to date. The remembrance and consciousness of injustices suffered by Sarajevo Serbs during the siege are essentially self-censored by a Serbian minority that tries to keep a low profile in the city and whose process of mourning is conducted strictly in private and within the community. In contrast to the discourses of officially repressing and self-censoring these memories, Serbian politicians and Serbian victims’ associations in Serbian-dominated East Sarajevo and Banja Luka, the seat of government of Republika Srpska, are quite aggressive and confrontational in dealing with the topic, even manipulating the number of victims.

Local media have reported sporadically on crimes against members of the Serbian and other minority communities in Sarajevo, but there has yet to be an in-depth investigation of the specific situation of minorities in the city during the siege.[19] Any efforts to commemorate Serbian war victims are complicated by the systematic expulsion and extermination of the non-Serbian population perpetrated by the army of Republika Srpska and Serbian paramilitary units during the war. One consequence of this is that no memorial ceremony on the day of remembrance for the murder of Sarajevo Serbs (26 October) has been organised by official representatives of the federal city administration or by civil society groups at the Kazani ravine. It was not until 2014 that representatives of civil society and the head of the OSCE in BiH, Jonathan Moore, took part in a memorial ceremony at all. The initiator of this memorial event was the then vice president of the Federation of BiH, Svetozar Pudarić, himself of Serbian descent and a member of the Social Democratic Party. For the past four years on the day of remembrance, he has paid a visit – initially on his own – to the Kazani ravine in the Trebević massif of Sarajevo, where the bodies of murdered Sarajevo Serbs and others were dumped.

During the first two years of the war, soldiers of the 10th Mountain Brigade of Bosnia and Hercegovina, under the leadership of rebel commander Mušan Topalović Caco, were purported to have terrorised and murdered Serbian and Croatian citizens. The precise number of victims is still unknown. According to police investigations, 110 Serbian men and women were killed in this fashion during the Siege of Sarajevo.[20] Staša Košarac, former director of the working group for investigating war crimes in the Ministry of the Interior of Republika Srpska, claims that 3,299 Serbian men and women were killed in Sarajevo, whereas about 5,000 were allegedly held in 126 camps throughout the city.[21] Three exhumations have been conducted to date in the Kazani ravine, yielding the remains of a total of 23 human corpses. Fifteen of the victims were identifiable. A total of fifteen former soldiers of the 10th Mountain Brigade under Commander Topalović have been prosecuted to date in different Sarajevo courts for their involvement in the Kazani incident.[22]

The crimes against minorities in Sarajevo were long buried in silence. Neither in the Kazani ravine nor in the city itself was there a plaque commemorating these Serbian victims. Svetozar Pudarić, after being elected vice president of the Federation of BiH in 2010, has been successful in his endeavours to fill this gap. In 2013, the city administration resolved to install a commemorative plaque in the Kazani ravine. The proposal has yet to materialise.

On 21 September 2014, in response to the delayed recognition of crimes against Sarajevo Serbs, the association of former camp inmates from Republika Srpska erected at Zlatište a ten-meter-high memorial cross for the 6,500 Serbs of Sarajevo who were allegedly murdered, according to the association’s director, Branislav Dukić.[23] This willful act on the part of the victims’ association did not receive the blessing of the city administration in East Sarajevo. On 5 December 2014, the cross, well visible from the city center, was sawed off by 27-year-old Mirza Hatić, who like many of his fellow citizens in Sarajevo perceived it as a provocation.[24]

Mušan Topalović Caco himself was killed on 26 October 1993 in a lightning attack under the code name "Trebević II", which was ordered by the president of BiH, Alija Izetbegović, and carried out by units of the Bosnian army and police. The objective of this highly dangerous secret operation was to stop the murder of Serbian citizens and remove this troublesome commander widely known to have criminal ties. Topalović was buried secretly, exhumed in 1996, and – in one of the many contradictions of post-war Bosnia – reinterred as a national hero. Nine police officers perished in the large-scale joint military and police operation, the oldest being 34-year-old Izet Karšić, the youngest 19-year-old Elvir Šovšić. Edina Kamica, a journalist for the daily Oslobođenje, called the triple memorial ceremonies on 26 October 2014 a "triple stigma"[25] for Sarajevo. In paradoxical fashion, the victims and their perpetrators were commemorated at three different locations on this day. Those commemorating the Serbian victims of violence in Sarajevo (Kazani ravine) and the Bosniak policemen killed during the joint operation (city park)[26]are relatively few in number. The community gathering around the grave of Topalović (Kovači Martyrs’ Memorial Cemetery) was a sizable one, on the other hand, many of them his former comrades-in-arms, who honoured their deceased general as a defender against Serbian aggressors and hardly considered him a war criminal.

The reluctance to admit one’s own guilt and misdeeds is a generalised phenomenon, and yet certain specific features can be identified in this case. The unwillingness of the primarily Bosniak majority in Sarajevo to publicly acknowledge the crimes against the Serbian minority during the siege is linked, among other things, with the understandable fear of relativising the deep-seated traumas of betrayal, bombardment and brutality at a moment when the sincere and unconditional admission of the suffering inflicted on the besieged city of Sarajevo has yet to come from the Serbian side. Mirsad Tokača, director of the Research and Documentation Center (Istraživačko-dokumentacioni centar) in Sarajevo, warns that "falsifying the numbers at Kazani" might be an intentional strategy "to create a counterbalance to the Siege of Sarajevo".[27]

The Serbian community in Sarajevo is by no means a homogeneous bloc, however. It leads a relatively inconspicuous existence in the federal zone of the capital, the silent public symbols of Orthodoxy and Serbian culture speaking on its behalf, seemingly confirming the city’s self-image as a multicultural space. Admittedly, the air in this space can become rather stuffy, and the dialogue between cultures difficult, when the living voice of those who survived the siege as a discriminated minority is added to these silent witnesses.

The future of multicultural coexistence in Sarajevo, however, does not depend on these abundant silent symbols of otherness, but on the ability to show tolerance for diverging and sometimes compromising experiences during and after the siege. In addition to inquiring about the behavior and responsibility of political leaders, it is important to consider how normal citizens of Sarajevo react to evidence and reports of discrimination against minorities during and after the war. The reactions of Sarajevo Bosniaks are generally dismissive, and marked by a fundamental skepticism regarding the credibility of such reports. In their self-image they see themselves as the true upholders of a long tradition of multiculturalism, and the crimes against Serbs and the discrimination suffered by other minorities do not comport with this self-ascription. Upholding this self-image apparently requires denying the victimhood of others. The more recent developments described above do, however, indicate that the rigid narrative of the last two decades is now being broken, supplemented or modified to a certain extent by new insights and facts that were hitherto denied.

The institutionalised minimisation, revision and sometimes denial of a genocidal policy against the non-Serbian population in Republika Srpska has proven to be highly inhibitive to a respectful and self-critical engagement with the recent past and the asymmetrical power relationships that prevailed during the war. As the army of Republika Srpska committed the bulk of the crimes during the Bosnian War, the Serbians victimised by other ethnic groups are either scarcely acknowledged or are considered a priori guilty, and hence marginalised in the public sphere. The lack of mutual recognition for the suffering of others and the refusal to admit one’s own guilt has led to strategies of remembrance that tend to hinder an appreciation of the suffering endured by members of the war generations, while burdening subsequent generations with a past that has not yet been mastered. The well-being of the minority postwar generation cannot be made dependent on their parents’ admission of guilt and imposed as a prerequisite to integration. It is up to the courts to establish individual guilt for specific war crimes.

The shrinking of minority communities can be stopped if the problems between majority society and these meanwhile self-ghettoising minorities is addressed openly, professionally and matter-of-factly. The academic community, civil-society groups and politicians, as well as members of the media will have to face these challenges if they seriously wish to question these entrenched positions and unrealistic expectations. A wealth of expertise on cultures of memory and remembrance as well as conflict transformation has accumulated in the last two decades in the sphere of civil society. With the support of professionalised activists and careful guidance, minorities could try to find suitable forms of presenting their experiences of war and the postwar period in the public sphere. The accumulated conflicts of coexistence could be reflected upon in cooperation with experts in the educational sector and at academic institutions. The questions posed by Haris Jusufović, a 34-year-old history teacher and survivor of the Siege of Sarajevo, would be a good start: ‘I don’t want to speak about the Siege of Sarajevo. Every decent human being is deeply conscious of and appalled by what my city went through from 1992 to 1995. [...] I want to hear the truth about what happened to my Serbian neighbors in Sarajevo. I want to know who is responsible for these crimes, who gave the orders, who carried them out, and in what political context the war crimes of Sarajevo took place. I want to know why my neighbors were taken away in the middle of the night. I want to know who shot and killed two girls playing in Grbavica.'[28]

Translated by David Burnett

Ljubinka Petrović-Ziemer: Cultures of Remembrance in Sarajevo, or the Protracted Search for Multiperspectivity and Integration. In: Cultures of History Forum (15.09.2015), DOI: 10.25626/0043.

Copyright (c) 2015 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

Official Website of the Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegowina, Sarajevo

Official Website of the Gallery "Srebrenica 11/07/95", Sarajevo

Official Website of the Fama Collection: Virtual Museum of the Siege of Sarajevo

Radio Free Europe reporter Omer Karabeg interviewing Svetozar Pudarić (former Vice President of the Federation of BiH) and Mirsad Tokača (Director of the Reseach and Documentation Center, Sarajevo) on the crimes committed against Sarajevo Serbs during the siege: "Zna li se istina o Kazanima?" ("Do we know the truth about Kazani?", 16.11.2014)

Interview by Denis Džidić (Balkan Investigative Reporting Networking) with the German-French historian Nicolas Moll about war crimes against Serb civilians during the siege of Sarajevo: "Our Hero, Your Killer: A Sarajevo Story", 10.8.2015

Short Film on Memory Cultures in the Western Balkans "MOnuMENTImotion" by Forum Ziviler Friedensdienst e.V. in Sarajevo (ForumZFD e.V. Sarajevo) and the Sarajevo-based artist Muhamed Kafedžić Muha

Official Website of the Youth Initiative for Human Rights

Official Website of the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network

Official Website of the Center for Nonviolent Action

Official Website MemoryLab (Trans-European Exchange Platform for History and Remembrance)

Official Website Friedensnetzwerk in Bosnien und Herzegowina (Mreža za izgradnju mir u Bosni i Hercegovini)

Nicolas Moll · 12.04.2015

Division and Denial and Nothing Else? Culture of History and Memory Politics in Bosnia and Herzegov...

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).