19. Dec 2018 - DOI 10.25626/0092

Dr Violeta Davoliūtė is Professor at the Vilnius University Institute of International Relations and Political Science and currently fellow at the Imre Kertész Kolleg in Jena (Germany). In autumn 2016 she was Visiting Professor at EHESS, Paris and an Associate Research Scholar at Yale University from 2015-2016. Her research focuses on the politics of memory, trauma and the ethics of representation as well as the legacy of war propaganda in Central and Eastern Europe. She received her Ph.D. from the University of Toronto.

This summer, the online magazine Salon published an article entitled “My grandfather wasn’t a Nazi-fighting war hero – he was a brutal collaborator.”[1] This filial confession by Lithuanian-American writer Silvia Foti – until then unknown to the Lithuanian public – sparked a limited but acrid discussion about who has the right and authority to pronounce judgement on the nation’s history both from within Lithuania and Lithuanian émigré circles.[2]

This controversy had less to do with the historical facts in play – namely the Nazi occupation of Lithuania from 1941-1944 and the Holocaust – than with their interpretation. Since the restoration of independence in 1991, Lithuanian historians, educators and public figures have rather extensively documented and to a degree explained the Holocaust as well as the role that many Lithuanians played as collaborators with the Nazi occupational regime.[3] This process, however, was partially driven by external pressure, performed in a formalistic manner, and yet fiercely resisted by certain segments of the native elite. Sharp controversies over the memory of the Second World War continue to erupt, suggesting that the Lithuanian ‘working through the past’ is not over and may be entering a new phase.

Influenced by genres of Holocaust testimony characteristic of Western Europe and North America, the transnational Lithuanian memory of the Second World War is oscillating between the public and the personal. In this article, Foti’s text and other works of autobiographical nonfiction are examined to reveal an emerging divergence between public celebrations of armed resistance as a secular religion and intimate explorations of a troubled past.

Born in Chicago to a family of Lithuanian immigrants, Sylvia Foti was raised on the stories of her grandfather’s heroism and suffering. Jonas Noreika was lauded in émigré circles as a hero who fought the Nazis and the Soviets, defending the nation’s independence from the outbreak of the Second World War until he was captured, tortured and executed by the Soviet secret police in 1947.

Approximately one hundred thousand Lithuanians fled the Soviet advance towards the end of the Second World War, maintaining a high level of cultural and political activity throughout the Cold War in North and South America, Western Europe and Australia. As the Soviet Union collapsed, they played an important role in reshaping the native Lithuanian discourse on the past, including the re-emphasis and re-valorisation of the anti-Soviet partisans who had continued, after the war, to fight the Soviet occupation and who had been denigrated as petty criminals by Soviet propaganda for over fifty years.

In 1997, Foti herself published a short hagiography of her grandfather in the émigré journal Lituanus, as an introduction to the fairy tale the Lithuanian hero, better known by his nom de guerre General Storm (Generolas Vėtra), had written while imprisoned in Stutthof, a German concentration camp during the last year of the Second World War. The tale was passed down, unfinished, as a series of fragments appended to the letters Noreika had written to his wife.

Assembled, edited and completed by Foti, the fairy tale is about an evil witch who invades the Kingdom with an army of frogs, and turns the children of the Kingdom into frogs. The King and his men fight back, but they are vanquished. Foti describes the story as Noreika’s way of explaining the family’s predicament to his six-year-old daughter through an allegory of the struggle for national independence. In the ending Foti devised, the fallen King’s daughter never gives up hope. She restores the frog-children back to their native condition by giving each one a kiss. The revived children fight, and defeat the frog army, sending the wicked witch back to her own land.

Noreika’s real-life daughter – Foti’s mother – would act out this allegory, keeping the faith and spending years gathering materials for a biography of her father. Shortly before her death, after Lithuania had already gained its independence, Noreika’s daughter secured a promise from her own daughter Silvia to finish this task and make her grandfather’s heroic story known. But as Foti dug into the materials and exchanged information with other researchers and memory activists, the project that began as a fairy tale soon took the shape of an indictment. For as the author soon discovered, before Noreika was arrested by the Germans in 1943, he had served as an official in the German-controlled local administration. Foti also discovered evidence of her grandfather’s anti-Semitism and how her family benefited from the property of murdered Jews.

Foti’s 2018 article in Salon reads like a short detective story, relating the steps of an investigator tearing down illusions and false premises to reveal the shame of collaboration. It aroused strong indignation in Lithuania, less for the facts that she relates, which are by and large accepted as a matter of historical record, but rather for the emotional tone and filial betrayal perceived in the work of a blood relative of a national hero.

No less shocking was the fact that this critique of a national hero should come from the émigré community, who for so long had steadfastly fostered the heroic narrative of resistance. One commentator denigrated Foti as a “Hollywood version of Pavlik Morozov from beyond the Atlantic,”[4] a strained and but telling reference to the story of a 13 year old Russian boy who denounced his parents in 1932 to the Stalinist authorities, and was subsequently killed by his family in revenge. In short, Foti was seeking to benefit from the tragedy of her grandfather, who lived in a time and place she could not understand and, by extension, belittling the tragedy of people, who bore the burden of shifting occupational regimes on their shoulders.

While the rhetoric in reaction to Foti’s text was strong, public attention soon moved on, as hers is just one of several exposés to have been published on Noreika in recent years. One of Foti’s key collaborators, Holocaust memory activist Grant Gochin, has even filed a civil case against the Genocide and Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania, contesting the Centre’s assessment that Noreika’s involvement in the Holocaust “cannot be judged unequivocally.” In January 2019, a Vilnius court will hear the case. A complete collection of court filings and arguments can be found on Sylvia Foti’s website.

The story of Noreika’s rise and fall as a post-Soviet hero captures many of the dynamics inherent to recent politics of the past in this region. At the outbreak of the Second World War, Noreika was an army captain and a lawyer. When the Soviets invaded in June 1940, he, like most Lithuanian officers, was consigned to the reserves. When the Germans launched operation Barbarossa one year later, Noreika took part in the June Uprising, an effort by Lithuanians to oust the Soviets and form a Provisional Government before the invasion of German forces, in the course of which the first pogroms against Jews took place, notably the notorious Lietūkis garage massacre in Kaunas.[5]

The German authorities, however, were not prepared to grant even political autonomy to Lithuania. The Provisional Government was not actively suppressed, but rather supplanted by the Reichskommissariat Ostland, the German civil administration for the occupied territory of Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Belarus, although Lithuanians continued to staff the police and local government.[6]

It was in this capacity, as members of local governments or various police and security forces, that many Lithuanians became complicit or participated one way or another in the Nazi’s genocidal enterprise. Most of the killing took place from June to December 1941. Over 90 per cent of all Lithuanian Jews, who numbered over 200,000 before the war, were murdered before the German army retreated from Lithuania in 1944.

Jonas Noreika was the governor of Šiauliai county from August until the end of September 1941. In this capacity, he was responsible for the establishment of the ghetto in the town of Žagarė, and for the transfer of Jews to the ghetto, from which they were taken to the killing pits nearby. Noreika is said to have joined the anti-German resistance only in 1942, before his arrest and imprisonment in February 1943. When the Germans retreated in 1944, Noreika was evacuated from Stutthof. Although he had the opportunity to flee to the West with his family, he elected to return to Vilnius. He managed to find employment as a legal advisor to the Soviet Lithuanian Academy of Sciences, and soon became engaged in the anti-Soviet resistance, where he demonstrated exceptional leadership and valour before his arrest, torture and death in February 1947.

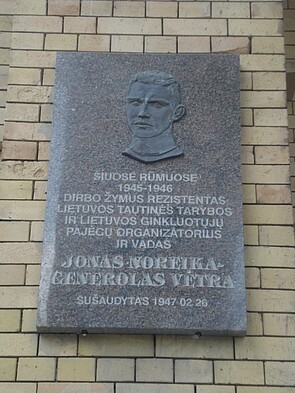

Fifty years later, in 1997, Noreika was rehabilitated by the government of independent Lithuania and posthumously awarded a high military honour, the Cross of Vytis, first class. A school was named after him and a memorial plaque was placed on the wall of the Wroblewsky Library, part of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences in Vilnius. His elevation to the national pantheon of heroes was part of a broader effort to commemorate the June Uprising and the Provisional Government as proof of the Lithuanian nation’s resistance to the imposition of Soviet rule in June 1941, which compensated for the absence of armed resistance in June 1940, when the Lithuanian leadership caved under Soviet pressure.

This campaign gained momentum with the transfer and reburial of the remains of Juozas Ambrazevičius-Brazaitis, the ostensible Prime Minister of the Provisional Government, from the United States to Lithuania in 2012. This event provoked a counter-reaction and increased scrutiny into the involvement of figures from the Provisional Government, notably Noreika, in the Holocaust.

In 2015, a group of intellectuals led by Sergey Kanovich, including Vytautas Toleikis, Tomas Venclova and the late Leonidas Donskis, signed an open letter demanding that the commemorative plaque be removed from the library building of the Academy of Sciences. The popular journalist Rimvydas Valatka wrote a scathing critique of Noreika as a collaborator, condemning the ongoing effort to make him into a hero as misguided.

The outcome of the court case, scheduled for January 2019, is still pending. The terms of the public debate have meanwhile shifted from the figure of Noreika, to a more nuanced discussion about how to promote the positive legacy of the struggle for national independence without glossing over the complexities of history and falling into the trap of one’s own propaganda.

In September 2018, Foreign Minister Linas Linkevičius asserted that by seeking to defend Noreika’s personal reputation, Lithuanians were adding wood to the fire of Russian propaganda and discrediting the legacy of the anti-Soviet resistance:

We must not help the propagandists. When we have incontestable facts of collaboration, we must respond in a principled manner. Noreika is one such case. It is true that he was in a concentration camp and struggled for Lithuania. But it is also true that, in front of my eyes, I have documents that bear witness to clear collaboration with Nazis, to the formation of Jewish ghettos, to the appropriation of Jewish property. The Municipality of Vilnius, the Academy of Sciences, and the Wroblewski Library must not shift responsibility from one to the other; they should take action to remove the plaque. There must be no doubt about this.[7]

Today, the plaque on the wall of the Academy of Sciences, where Noreika worked in 1946, remains in place (see picture). The Mayor of Vilnius and the municipality are in no rush to remove it, and candidates for the upcoming presidential elections downplayed the need to take action during a recent debate. Thus former EU ambassador to Russia Vygaudas Ušackas told the media that

the Minister of Foreign Affairs should keep quiet. He is neither a judge nor a historian. General Storm is a Lithuanian hero, a freedom fighter, and it is not the place of the Foreign Minister to judge him.[8]

Ironically, Sylvia Foti’s intimate exploration of her family’s burdensome past appeared just as the public discourse on heroic resistance peaked, with the dedication of Lithuania’s centenary year to the memory of Adolfas Ramanauskas-Vanagas, a partisan leader born in 1918, and the re-dedication of Lukiškis Square, the former Lenin Square, to the anti-Soviet armed resistance.

The remains of Ramanauskas-Vanagas were discovered in a Vilnius cemetery, identified through DNA analysis, and reburied in a high-profile state funeral in October 2018. In November, the Lithuanian parliament posthumously elected Ramanauskas-Vanagas to the post of the Lithuanian head of state for the period from 26 November 1954 to 29 November 1957. The historians consulted by Parliament on the issue were against the election, citing the lack of evidence that Ramanauskas viewed himself as the head of state or of the actual existence of a Lithuanian state at the time. According to historian Alvydas Nikžentaitis, the decision of the parliament amounts to a rewriting of history for the sake of politics.[9] Other scholars, including law professor Vytautas Sinkevičius, consider the de jure continuity of Lithuanian statehood, recognized under international law, to be a sufficient basis for the election.

However, these academic debates were of little concern to parliamentarians. Their position was best represented by the remarks of MP Povilas Urbšys (a relative of the last interwar foreign minister, Juozas Urbšys), who stated that Lithuanian historians could have their conferences for as long as they wanted, but politicians would go ahead and make political decisions.

Meanwhile, beneath the storm of these thunderous political debates about national identity and the continuity of statehood, a deeper current of personal explorations into family history is gaining pace. As a genre, private excavations of a shared past are well-known in North America and Western Europe. Critics describe such works as a manifestation of second and third generation ‘post-memory,’ filling in the gaps of what the author’s parents and grandparents tended to side-line or to forget. Like the testimonial literature of children of Holocaust survivors, they are preoccupied with the ethics and the aesthetics of remembrance in the aftermath of genocide. Heavily invested into the linkage of emotion and identity, they are by far the most popular form of literature on the Holocaust, because they ask gripping questions like: How do we regard and recall the pain of others? What is our debt to the victims? How can the remembrance of genocide be channelled into responsible action?

Although common in North America, such literature is rare in Lithuania. Indeed, at least some of the controversy raised by the bestselling book by Ruta Vanagaitė, can be attributed to its genre: Instead of a dry work of academic history, Vanagaitė attracted an unprecedentedly large Lithuanian and international readership by offering a personal and emotional engagement with a deeply traumatic subject matter – the participation of Our People in the Holocaust.[10]

While Vanagaitė and Foti have attracted the most attention, at least two other books by women from the Lithuanian émigré community have been published in recent years: Rita Gabis’s A Guest at the Shooters' Banquet: My Grandfather's SS Past, My Jewish Family, A Search for the Truth and Julija Šukys’s Siberian Exile. Blood, War, and a Granddaughter's Reckoning (2017).[11]

Both Gabis and Šukys are the granddaughters of men who served in the Lithuanian police forces under German occupation. Each woman grew up surrounded by silence in regard to parts of their family history and felt compelled to investigate it by descending into the archives and telling the story of Lithuanian participation in the Holocaust in an act of personal and collective self-discovery.

Born to a mixed Jewish-Lithuanian family, Gabis’s confrontation with the Holocaust began with an effort to reconcile conflicting family memories. The reader quickly understands the tremendous scope of her research, which spanned several countries and extended from the archives to interviews with family members and long discussions with professional historians. Her writing is deeply personal and meditative, showing a deep engagement with the subject. The book was very well received among critics in North America: Yale Historian Timothy Snyder called it a “true-life Bildungsroman [that] sets an example, in its honesty, industry, and artfulness, for writers who wish to confront the past.”

The book is not available in Lithuanian translation, and it has not been reviewed in Lithuania as such. The few published comments from émigré historian Augustinas Izdelis in the Lithuanian media show little appreciation for the testimonial value of her work, by criticizing historical inaccuracies, her reliance on foreign as opposed to Lithuanian perspectives, and a lack of contextual knowledge.

For her part, Julija Šukys began work on Siberian Exile with an exclusive focus on the life story of her grandmother, Ona, who was deported to the Gulag by the Soviets in June 1941. It was almost by accident that she turned her attention to the Holocaust, after she made an inquiry to the Special Archives in Vilnius for any material on her grandfather, Anthony. Only after receiving over one hundred pages of police files on her grandfather’s collaboration with the German occupational forces in Vilnius did Šukys come to understand that her family’s memory had until then been “organized by silence.”

There was always, for example, a great hush surrounding the years from 1941, the year Ona was deported to Siberia, to 1944, when her husband, Anthony, and their three children fled westwards. These years demarcated the Nazi occupation of Lithuania. Anyone telling us children the story of our family history inevitably jumped from Ona’s arrest and deportation straight to her children’s dramatic departure in 1944. I was almost an adult before I realized that the second event hadn’t followed immediately on the heels of the first. Indeed, so total was the silence surrounding the German occupation, and not only in our family, that I was fifteen before I realized that the Holocaust had anything to do with Lithuania.[12]

Like Gabis, Šukys proceeded to write a personal exploration of her family’s forgotten past, of her grandmother Ona and grandfather Anthony. Šukys also reached far beyond her own family, consulting historians and archives as well as interviewing individuals from neighbouring communities of memory, ranging from Vilnius Jews to Polish Siberians. As she told the author in a personal conversation, she had initially been quite anxious about the reaction of the broader émigré community, but she ultimately received high levels of family and community support for the project.

Her book was well received in North America, winning the American Association of Baltic Studies book prize and the Vine award for Canadian Jewish literature, but like Guest at the Shooter’s Banquet, Siberian Exile has yet to be translated or discussed in Lithuania. Until that happens, one can only speculate how the broad Lithuanian public will react to the intensity with which Šukys uproots the past and challenges existing narratives. In one passage, while studying a photograph of her grandfather as a young man in 1923, she considers “an awful almost unspeakable question,” about how his life might have turned out for the better if only he had been deported by the Soviets in June 1941:

Had he been taken with Ona, none of the accusations outlined in the KGB files would have existed. He would have been far away when the Germans came and when the Jews were shot. He would never have been faced with the choice of whether to become a cog. In this alternate and, yes, selfish history, where I can change only one life, Anthony would have been a clear, clean victim. A hero, even. Is it possible that the tragedy wasn’t Ona’s deportation but her husband’s escape? (pp. 66-67).

As these examples show, the time for a more personal exploration of the past in Lithuanian public memory has clearly arrived. In his glowing review of Gabis’s book, Snyder writes, “Maturing from childhood to adulthood means accepting a place in family stories. Checking treasured myths against historical facts is like a second coming of age, and one rarely achieved.”

While the principal challenge to established narratives may still be originating from the younger generations of the émigré community, it is by no means absent in Lithuania proper. In tandem with recent moves towards the politicization of history, Vanagaitė’s Our People, just like Sigitas Parulskis’ 2013 novel Darkness and Company, signal the emergence of a personal and polemical approach to an uncomfortable past. In a globalized world where Lithuanian and Jewish, émigré and native, first, second and third generation memories are increasingly intersecting, forgetting is not an option, and the silences of the past will not last.

Violeta Davoliūtė: Between the Public and the Personal: A New Stage of Holocaust Memory in Lithuania. Cultures of History Forum (19.12.2018), DOI: 10.25626/0092

Copyright (c) 2018 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

The personal website of Silvia Foti "In search of the truth" where she provides further sources and information about her "quest for the truth on Jonas Noreika."

Statement by the Jewish Community of Lithuania (Lietuvos žydų bendruomenė) "Regarding Jonas Noreika", 27 July 2018.

See also the news report by Andy Roesgen, Granddaughter Unmasks Lithuania's WWII Hero as Jew Killer, i24NEWS (24 September 2018)

Violeta Davoliūtė · 30.09.2023

Lithuania’s Postcolonial Iconoclasm – or Politics by Other Means

Read more

Violeta Davoliūtė · 29.09.2021

Trials and Tribulations: The Lithuanian Genocide and Resistance Research Centre Reconsidered

Read more

Violeta Davoliūtė · 17.11.2017

Heroes, Villains and Matters of State: The Partisan and Popular Memory in Lithuania

Read more

Ekaterina Makhotina · 27.09.2016

We, They and Ours: On the Holocaust Debate in Lithuania

Read more

Rasa Baločkaitė · 12.04.2015

The New Culture Wars in Lithuania: Trouble with Soviet Heritage

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).