01. Jun 2022 - DOI 10.25626/0138

Violeta Davoliūtė is Professor at the Vilnius University Institute of International Relations and Political Science. Having received her Ph.D. from the University of Toronto, she held visiting professorships and research fellowships at EHESS, Paris, Yale University and the Imre Kertész Kolleg in Jena. Her research focuses on the politics of memory, trauma and the ethics of representation as well as the legacy of war propaganda in Central and Eastern Europe.

While Putin’s plan to launch a full-scale invasion of Ukraine has been widely understood as irrational, it is entirely consistent with the “anti-fascist” discourse of his regime. Though it seems contrived to outsiders, this discourse resonates powerfully with both Russian troops in the theatre of war and among citizens at home. Rooted in Soviet culture, it draws on the political and cultural neo-traditionalism that crystalized in Soviet television serials in the 1970s, which vilified the West, defined a new Soviet war hero, and nurtured a cryptic fascination with Nazism. From this perspective, the invasion of Ukraine can be interpreted as a case of life imitating art: irrational from the perspective of national interest, but true to life in terms of plot.

Vladimir Putin stunned the world on 24 February 2022, when he announced that Russia had embarked upon a full-scale invasion of Ukraine – dubbed a “special military operation” – in order to "de-Nazifying" Ukraine. The economic and human costs made the invasion improbable, the calculus of national interest impenetrable, and the narrative used to justify it implausible. The claim that Volodymyr Zelenskiy – a Russian-speaking Ukrainian with Jewish relatives who fought against the Nazis during the Second World War and perished in the Holocaust – was the leader of a fascist junta made jaws drop across Europe. The notion that 'the West' was promoting Nazism in Ukraine as a means of threatening Russia was seen as little more than geopolitical gaslighting.

It took weeks of war and the revelations about the atrocities committed by Russian troops before certain Western officials came to terms with the 'new' reality. Admitting to the failure of Germany’s foreign policy vis à vis Russia, President Frank-Walter Steinmeier said that he “did not believe that Vladimir Putin would embrace his country’s complete economic, political and moral ruin for the sake of his imperial madness.”

For scholars in the field of memory studies, the method to Putin’s "madness" is all too familiar: Russia’s political leadership and propaganda outlets have labelled Ukraine as a fascist state since the initial invasion in 2014. Specifically, they revived an anti-fascist discourse fashioned in the 1960s, during the Cold War, in which the Soviet victory over Germany in the Second World War was fashioned into the main pillar of political legitimacy, displacing the October Revolution as the founding myth of the regime.[1] The persuasive strength of this discourse lies in the way it relies on what Raymond Williams calls “structures of feeling,” or the social acceptability of discursive conventions, for its plausibility. Embedded in Soviet and post-Soviet culture, this anti-fascist discourse has been increasingly mobilized to generate an affective response in the Russian population based on the memory of the Great Patriotic War that “amorphously alternates between valences of nostalgia, feelings of reliving history and a collective desire for the restoration of Russia as a great geopolitical power.”[2]

The resonance of this discourse is evident in recent public opinion polls and the actions of Russian troops in Ukraine. It has “considerable traction among average Russians,”[3] and Russian conscripts are propagandized to believe that they are fighting Nazis. In a video distributed by the Russian Defence Ministry, a marine commander affirms his pride in following in the footsteps of his grandfather, who “chased fascist scum through the forests”, including members of the anti-Soviet resistance, during and after the Second World War.[4] Perhaps paradoxically, the discourse of anti-fascism has adopted the iconography of Nazism: Based on the widespread use of the ‘Z’ symbol, stylized as a semi-swastika, and the glorification of military violence by the public, Mikhail Epstein has diagnosed Russia’s descent into “schizofascism,” defined as “fascism that is hiding under the mask of fighting against fascism.”[5] While the spread of these symbols has led to comparisons between Russia and Nazi Germany, Marlene Laruelle notes that Putinism is able to draw on more proximate totalitarian ideological traditions.[6]

Ultimately, the anti-fascist discourse prevalent in Russia today represents a revival of a 1970s Soviet neo-traditionalism, including a cryptic fascination with Nazism nurtured through a popular television series that glorified a Soviet spy working undercover as a Nazi official. This discourse is rooted in a categorization of the self and the other, including targeting and excising the enemy within, and in the glorification of the Great Russian security service agent as a powerful war hero and example of national valour. The narrative of the villain and the hero is expressed through anti-Western rhetoric leading to imperial hubris.

Originating in the anti-German propaganda of the Great Patriotic War, this discourse has evolved significantly over the course of the postwar period. In the 1960s, for example, it was mobilized to support the ideological integration of the recently annexed Western territories of the USSR, including the Baltic States, Western Belarus, Ukraine, and Moldova. Even as events in Hungary sent shockwaves throughout the Soviet bloc, Khrushchev’s amnesties allowed tens of thousands of people to return from the Gulag to these territories, their presumed anti-Soviet attitude ostensibly radicalized by the process of deportation. Having forsworn Stalinist-style mass repression, the regime mobilized ideology and the secret services to counter the impact the 'returnees' might have on the rest of the population. The targeting and social exclusion of individuals suspected of collaborating with the German occupation was a key element of this process. In comparison to the first wave of Stalin-era prosecutions from 1943 until 1953, which was massive and indiscriminate, with about 320,000 Soviet citizens arrested for collaboration, including 57,000 for treason and war crimes,[7] the second wave, which began during the Thaw, was selective and highly mediatized. Khrushchev amnestied tens of thousands of Soviet citizens who had served in the German army, police, and special units during the war but were considered rank and file accomplices (posobniki).[8] The investigations launched in the late 1950s that continued during the 1960s focused on the karateli, those who had direct involvement in the killing or torture of Soviet citizens.[9]

Building on the investigations, a series of highly mediatized show trials were held in several cities in the Soviet Western borderlands, as well as several East Bloc countries. A classified KGB report describes the trials an “active Chekist measure” meant to undermine the status of anti-Soviet elements as well as the ideological appeal of the West for Soviet citizens.[10] The mediatization of these trials extended beyond newspapers to include the production of literary works as well as films. The blockbuster adventure drama Enemy of the State (1964), for example, was based on a melodramatic plot that “tore the mask off” a villain who had collaborated with the Nazis during the war and was now pretending to be an ordinary Soviet citizen.

The unmasking of the “enemy within” was part of the reinvention of Soviet society in the wake of the Second World War and the finding of personae that fit the new post-Stalinist society.[11] Ukraine, Belarus, and the Baltics were presented as territories dominated by a hybrid identity – at once native and yet uncannily foreign, the enemy within, liable to betray the Soviet homeland owing to their hidden ties to foreign powers.[12]

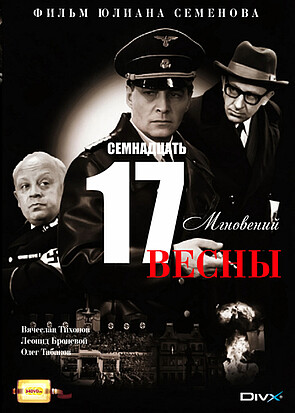

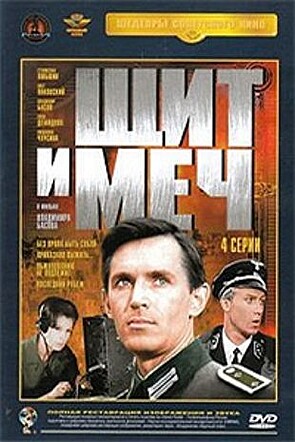

While the military dimension of the Cold War eased with the onset of Détente in 1967, the competition of ideologies intensified. Under Brezhnev, asserting the Soviet Union’s geopolitical supremacy trumped the Khrushchev era’s nurturing of more humanistic representations of the experience of war. The cult of the Great Patriotic War reached its apogee in the 1970s, driven by KGB efforts to cultivate an image of the secret service agent as a new Soviet superhero, superior to the West’s James Bond, through the patronage of television serials, most notably Shield and Sword (1968) and Seventeen Moments of Spring (1972). Working undercover as Nazi officers during the war, the Soviet secret agents in these productions were played by extremely handsome men dressed in glamorous Nazi uniforms. Moreover, they were presented as supremely gifted masters of disguise, rising effortlessly to the highest echelons of German society, yet remained true to their Russian identity and loyal to the Soviet state.

In Shield and Sword (Shchit’ i mech) for example, Alexander Belov (played by Stanlislav Lyubshin, born in 1933), a Russian spy, travels from Soviet-occupied Latvia to Nazi Germany under the alias of a Volksdeutsche named Johann Weiss. Moral dedication, nerves of steel and a quick wit, combined with his mastery of German language and culture, allow him to rise up the ranks of the German security services.

Both the originality and extraordinary popularity of the series were in large part a response to the lavish sets and costumes that allowed Soviet viewers an entrancing glimpse into German high society – including large, elegant venues, luxurious, modern cars and motorcycles, glamorous women and, above all, extraordinarily handsome men adorned in shining black leather, fighting for the Soviet state while drinking expensive cognac and driving fancy German cars. The protagonists move within a deeply homosocial environment, with women serving only to flesh out the glamorous setting. Weiss’s intimate friendship with Heinrich Schwartzkopf, an aristocratic Baltic German who travels with him from Latvia to Germany, adds a significant element of melodrama. When Weiss/Belov is ordered to establish contact with another undercover Soviet agent, he discovers that agent is none other than his close friend Heinrich, played by Oleg Yankovsky (1944-2009).

The alchemical transformation of a Soviet spy into a Nazi officer generated a sense of fantasy for Soviet viewers, inviting them to partake in the guilty pleasure of dressing in a black leather trench coat and inhabiting the glamorous lifestyle of a high-ranking German official during the war. Secret service officers were presented as a noble caste; the grit of military battles is only fleetingly woven into the series in the form of short newsreel clips of faceless soldiers.

The development of the secret agent as a Soviet superhero culminated in the figure of Otto von Stierlitz, the undercover identity of Maksim Maksimovych Isayev, the hero of Seventeen Moments of Spring (Semnadtsat’ mgnovenii vesny). Isayev is planted in Germany in 1927, before the Nazis come to power, where he enlists in the Nazi Party and is appointed to the counter-intelligence agency, where he is able to recruit German dissident intellectuals as his agents and schemes to disrupt Nazi plans, including an effort to forge a separate peace between Germany and the Western Allies. Like a true renaissance man, von Stierlitz is fully at ease discussing philosophy, religion, history, and science in several European languages. The secret agent reflects the ideal of the Russian intelligentsia, whose knowledge is matched only by his asceticism and modesty. In sharp distinction to the Western model embodied by James Bond, he rarely drinks and never indulges in sexual escapades. Surrounded by the riches of the Western world, the Soviet spy is unfailingly faithful to a higher ideal: his socialist homeland – not only in a transactional sense, but also moulding his character to remain true to its ethos.[13]

In Screen Nazis, Sabine Hake singles out these two television productions as key to the construction of a fascist “absolute other” to communism in late Soviet culture.[14] She also notes how they, like any effort to represent fascism in film, are impacted by the inner workings of fascist aesthetics. As if entranced by fascism’s imagery, symbols and rituals, post-fascist representations of fascism appear susceptible to “an almost obsessive re-enactment” of the aestheticization of politics (159). Noting the extraordinary, cult-like status of von Stierlitz, Hake argues that he came to represent the ideal Soviet man: “rational but still soulful, deeply patriotic, committed to the collective, and willing to suppress all individual feelings and desires” (174). Furthermore, given these qualities, the romanticized Soviet hero becomes impossible to distinguish from the ideal of the perfect Nazi: “the embodiment of duty, service, and commitment to the cause where the real Nazis are corrupt, power-hungry and weak” (174).

The idea that Soviet culture was marked by a “cryptic fascination with Nazism” is reinforced by the casting practices in place at the time. Yankovsky, who was propelled from Shield and Sword to becoming a star of Soviet cinema, was selected for the role because of his ostensibly “typically Aryan looks.”[15] An entire generation of actors was recruited from Lithuania and Latvia to fill the role of “Soviet Nazi” or simply of the Nazi niche, including Gunars Cilinskis, Donatas Banionis, Juozas Budraitis and Algimantas Masiulis among others. Paradoxically, these Baltic Soviet screen Nazis became cult figures in Soviet cinema. The fantasy of penetrating and mastering the West, along with the erasure of the visual markers between a Soviet 'us' and Nazi 'them' generated a sense of power and glamour and contributed to the popularity of these actors and the films they played in.

While many have sought to trace the influence of fascist thinkers on Putin’s political views, there is little evidence that he or any other high-level Russian decision-maker has ever engaged with such ideological matters on an intellectual level.[16] A more important factor in shaping Putin’s world view were, as Peter Rutland suggests, the novels and – even more importantly – the television shows that Putin is known to have consumed as a teenager. Putin has himself noted that he was inspired by Sword and Shield to become a KGB agent and learn German.[17] Indeed, the leading role of television in the creation and maintenance of the Putin regime, including the promotion of Soviet nostalgia, has been extensively described by industry insiders.[18] Not only did Putin-era television move away from the 1990’s focus on social issues in contemporary Russia, reverting back to representations of a strong and benevolent state.[19] Putinism as a whole revived the aesthetics and cultural practices of late socialism. Alexander Prokhorov, for example, notes an “affinity for 1970s culture and its visual texts."[20] In tandem, the defence and security services revived the late Soviet practice of sponsoring the production of feature films and television serials, awarding prizes to their favourites.[21]

Taken together, these productions project an image of a masculinist polity with complete control over Russia, the post-Soviet states and former Cold War rivals. Adulation of the secret service agent, including a fascistic appreciation for his superior phrenology, physique and ethics is evident in the paean to the FSB operative provided by Nikolai Patrushev: “intellectual analysts with high foreheads, seasoned commandoes with broad shoulders, quiet explosives specialists, stern investigators, discrete counter-intelligence officers. [...] Outwardly, they are different, but [they] are united by a life of service, a modern neo-nobility (neo-dvoriantsvo), if you will."[22]

Ultimately, tracing the lineage of this anti-fascist discourse in contemporary Russia back to Soviet-era visual culture is important to understanding its deep roots and thus its effectiveness in defining the self and the other. With the deterioration of Putin’s foreign relations with the West and the crackdown on democratic institutions, the regime has become marked by a geopolitical assertiveness, homosocial behavioural patterns and the aestheticization of politics,[23] which have their roots in this 1970s era visual culture and served to foster the neo-traditionalism of the late Soviet regime and overturn the progressive modernism of the Thaw. Popular films and TV series from this era played a key role in developing cultural archetypes that would come back to influence post-Soviet culture under Putin. They also help explain the evolution of collective memory in post-Soviet Russia and how it has differed from similar processes in the West. At a time when the population of West Germany was internalizing the tragic fate of the Jewish Weiss family in Holocaust (Dir. Marvin Chomsky, 1978), Soviet viewers were enthralled by the glamorous adventures of the Nazi/Soviet officers Johann Weiss and Otto von Stierlitz.

Finally, the idea that Russia’s radically anti-Western course was forged in the culture of the late 1960s and 1970s suggests the need to rethink the history of the Cold War and the notion of 1989/1991 as a watershed of European and global history and memory.[24]

Violeta Davoliūtė: The Pop-Cultural Lineage of Russia’s Anti-Fascist Discourse: Unravelling the Plot of Russia’s War on Ukraine. Cultures of History Forum (01.06.2022), DOI: 10.25626/0138.

Copyright (c) 2022 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editor.

Jeremy Cohen · 25.01.2023

Vladimir versus Volodymyr: Conflicting Russian and Ukrainian Application of Rus’ Heritage

Read more

Gero Fedtke · 27.08.2021

'Bukhenval'dskii nabat': The Life and Transformation of a Peace-Song in Soviet and Post-Soviet Histo...

Read more

Mykola Makhortykh · 28.06.2021

#givemebackmy90s: Memories of the First Post-Soviet Decade in Russia on Instagram and TikTok

Read more

Raphael Utz · 27.11.2020

Stalin in our Hearts. The Russian Film 'Sobibor' by Konstantin Khabensky

Read more

Anna Schor-Tschudnowskaja · 29.04.2020

A Pop-Cultural Reappraisal of State Terror? The YouTube Film 'Kolyma – Birthplace of Our Fear' and I...

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).