24. Jul 2017 - DOI 10.25626/0065

Dr. Andrzej Hoja has graduated in History from the University of Gdansk, where he also obtained a Ph.D. Since 2011 he has been involved as a curator in exhibition projects at the Pomeranian State Museum, Greifswald and the Gdynia City Museum. In 2016/17 he also participated in the certificate program "Exhibiting Contemporary History" at the Friedrich Schiller University of Jena. Among his academic interests are oral history, micro-historical approach at narrative exhibitions in museums, historical culture of Pomerania region and Polish-German relations.

In recent years, no other museum exhibition in Poland has aroused such strong feelings as the permanent exhibition of the Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk. At the same time, the exhibition, unlike any other of comparable importance, was able to entirely forgo self-promotion, as this was provided by the media, both Polish and international, which widely reported on the dispute between the Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage and the museum’s management. The dispute concerned the main storyline of the exhibition but, in fact, it had little to do with history and much more with current Polish politics. The considerable waves that the political dispute generated, unfortunately, has eclipsed more thorough and content-related discussions about the exhibition as such. The Polish public (as well as many professionals and historians) who have discussed the permanent exhibition in Gdańsk, tend to forget that an exhibition as such is, and should be, a multi-dimensional endeavour, going much further than merely presenting a selection of historical issues, allowing visitors to experience history in many different ways.

The Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk was officially established in 2008. A year later, the Belgian design studio NV Tempora S.A. won the competition for the design of the exhibition. In 2010, the Kwadrat studio based in Gdynia won the competition for the design of the museum building, which was to take the form of a tower, with the permanent exhibition being housed 14 metres below ground level. Two years later, construction work began in a central district of Gdańsk that had not been reconstructed after the Second World War and is located just a few minutes’ walk from the main tourist area of the Hanseatic city. In 2013, the No Label/New Amsterdam company from Kraków started work on the multimedia and audio-visual materials for the exhibition. The construction of the exhibition itself was commissioned in 2015 to a consortium led by the Warsaw-based Qumak S.A. company[1]. All those milestones in the process of creating the exhibition were ultimately reflected in its appearance.

Most importantly, a team of curators worked in parallel on the exhibition content. The general framework and storyline of the exhibition were the work of Professor Paweł Machcewicz, Dr Piotr Majewski, Dr Janusz Marszalec, and Dr Rafał Wnuk. In addition, nearly 20 curators[2] worked on individual aspects of the exhibition, and the project was supervised by an advisory board comprising an international panel of academics, all of whom are experts in the topics covered.[3]

Finally, on 23 March 2017, the permanent exhibition of the Museum of the Second World War <link debates poland on-polish-history-disputes-over-the-museum-of-the-second-world-war-in-gdansk>opened its doors to visitors.[4] Occupying approximately 5,000 square metres of floor space, it is among the world’s largest historical exhibitions devoted to the subject of the Second World War. It features around 2,000 original exhibits, and many more can be accessed digitally from one of the 240 multimedia stands.

The exhibition is arranged on the lowest floor of the museum. The space is divided by a clear axis – a corridor in which objects relating to daily life during the war and occupation are gathered in no particular chronological order. From the corridor, visitors can enter a room that offers an introduction to the entire narrative and can also access the 18 parts/spaces of the permanent exhibition. In the main hall, there is also a separate entrance to the exhibition for children.

The primary purpose of the permanent exhibition is to immerse visitors in a narrative about the global armed conflict that took place seventy years ago. The Second World War seems an almost ideal subject for such a narrative – a period neatly delineated in time (spanning just a few years), thrilling and dramatic, abounding in breakthrough moments that add dynamism to the story, and featuring countless heroes whose different attitudes perfectly illustrate the unique nature of the times in which they lived. It is thus an excellent subject upon which to base a museum narrative for modern visitors.

So what exactly is the exhibition about? This is clearly explained in the introductory text to the exhibition, which identifies three main layers of the narrative. The first is a story about the cataclysmic war “launched by the totalitarian regimes of Germany and the Soviet Union”; it includes both the personal tragedies of millions of individuals and the international dimension of the catastrophe, which affected numerous states and nations. This narrative is told mostly from the perspective of civilian victims of various nationalities.

The second layer is the story of Poland, which – as the authors point out – “already… on 1 September 1939 found itself in the eye of the storm”. In this way, the authors emphasise that the Polish perspective is an important part of the narrative. The exhibition thus features proportionally more topics and events related to Poland than to other participants of the conflict. In addition, the story of Poland is often used as a pretext to describe especially to West European visitors the fate of the populations of Central and Eastern Europe, a story with which they may be less familiar.

The third layer of the narrative has a universal message. The authors state in no uncertain terms: “The war’s experience remains meaningful today”. Wars continue to be waged and the suffering they cause affects millions of people. This layer of the narrative therefore concerns not only history but also human nature, and the problem of evil and how to oppose it.

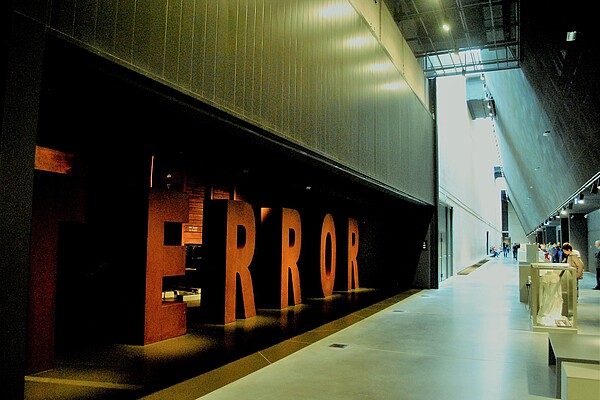

These three key messages – the magnitude of the catastrophe, the local perspective, and universalism – permeate the narrative of the exhibition, which is structured both chronologically and thematically. It consists of three main sections – an introduction entitled “The road to war”, a main part entitled “The terror of war”, and an ending: “The long shadow of war”. This division shows that the curators have framed their narrative of the war in broad terms. It begins in 1910 with the funeral of Edward VII in London – the last occasion on which international elites of the old order congregated in such numbers – and continues almost until the present day, revealing the consequences of the war and the way in which it divided our world.

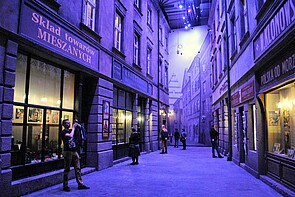

Before the section on the outbreak of war in Europe, visitors learn about the birth and expansion of three totalitarian states – fascist Italy, communist Soviet Union, and Nazi Germany. Then, moving through a “reconstructed” Polish street from the inter-war period, visitors observe world events as they unfolded prior to 1939 – the conflicts in Asia, the Spanish Civil War, rising tensions, and the policy of appeasement in Europe.

The main part of the exhibition – “The terror of war” – begins with the German attack on Poland, soon followed by the Soviet invasion of the country from the east. The September Campaign and the first days of the occupation are discussed here.

In the next part, the Winter War between the Soviet Union and Finland is depicted alongside warfare in the years 1940–1942, which is largely illustrated by the equipment of the soldiers and military units engaged in hostilities at that time. The exhibits include soldiers’ personal belongings, which give insight into life at the front or in prisoner-of-war camps. This part is dominated by the nose section of a Junkers Ju 87 dive bomber, which emerges from a wall.

The space entitled “Merciless war” introduces visitors to the suffering experienced by millions of ordinary citizens due to the criminal methods used to conduct hostilities. It begins with an installation devoted to the death of more than three million Soviet prisoners of war in German captivity. Visitors then witness the living conditions of civilian populations in the besieged city of Leningrad and in cities that were bombed (Tokyo, Warsaw, London, Dresden). They learn that starvation was either a result of the war itself or a tool deliberately employed by the occupying powers.

The part entitled “Occupation and collaboration” begins with an interactive quiz about the situation that prevailed in the occupied countries of Europe. It also compares the nature of the German, Soviet, and Japanese occupations and describes the various forms of collaboration and cooperation with the occupying powers. This serves as a preamble to subsequent spaces in which the most appalling forms of terror used during the war are discussed: the first cases of mass killings in Poland, deportations, forced labour, concentration camps, and finally the Holocaust and the attempts to annihilate national minorities (in the Balkans and Eastern Galicia).

The forms of resistance that were a response to this terror are presented in the next parts of the exhibition: the Polish Underground State, the resistance movement in Europe, and the rebellions against the occupier (the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, the Warsaw Uprising, and the uprisings in Prague, Paris, and Slovakia).

The narrative about the final years of the war covers such topics as the cracking of the German Enigma Code, economic mobilisation, and the Allied offensive of 1943–1945. The section entitled “The war is over” presents the negotiations between Allied leaders that had a direct impact on the shape of the post-war world, the flight of Germans before the advancing front, and the abuses perpetrated by Soviet troops. Other important topics touched upon are the liberation of the concentration camps and the public response to war crimes as well as the problem of lynchings and revenge. This part concludes with a discussion of the end of the war in Asia and the dropping of the atomic bomb on Japan.

The narrative does not end there, however – the story told in “The long shadow of war” concerns post-war migrations and the organisation of a world divided by the Iron Curtain, post-war reckonings and trials, material damage, and economic and human losses. The destroyed world is symbolised by a ruined city street with a Russian T-34 tank among the rubble. As the journey begins in the early 20th century, so it ends almost in the present day with an installation showing the fortunes of a divided post-war world.

To recap: the visitors’ route through the museum is long and winding but nonetheless well-marked, making it possible to move between the various parts of the exhibition quite intuitively. It was a good idea to locate successive parts of the exhibition on alternating sides of the main axis; when crossing it, visitors always find themselves in a space devoted to daily life during the war, and this reminds them that in the midst of all the drama, terror, and hostilities, most people had to struggle with everyday problems, trying to survive in the face of shortages and uncertainty.

As outlined above, the structure of the exhibition is fairly clear. The story of the war incorporates objects, photographs, texts, and scenography. Multimedia content, including films and music, is an important element of the overall presentation.

However, the narrative is centred on physical objects. Around 2000 of them are included in the exhibition and they serve to guide visitors through the story of the war. These objects are incredibly diverse. In terms of size, they range from U.S. M4 General Sherman and Soviet T-34 tanks to figurines from the Jasenovac concentration camp in Croatia and victims’ buttons found in the Katyń forest, where Polish military officers had been shot by the Soviets in 1940 (see pictures). Many tell highly personal stories, one example being a secret letter written on a handkerchief by Bolesław Wnuk, who was imprisoned and murdered by the Nazis in Lublin in 1940. Others are more symbolic, such as a plaque bearing the Polish national emblem from the Polish-Soviet border, which was removed and thrown into the Zbruch River in the autumn of 1939.

It is evident that the authors have tried to satisfy the curiosity and meet the needs of a wide range of visitors. There are weapons and uniforms of various military units as well as objects that either testify to war crimes (victims’ or perpetrators’ personal effects such as keys belonging to Jews murdered in Jedwabne or a whip from the Gross-Rosen concentration camp) or simply illustrate daily life in wartime (ration books, household items, means of transport).

In some cases, the authors have attempted to engage in a dialogue with other exhibitions. One example is a railway wagon used by Polish State Railways during the inter-war period. Subsequently appropriated by the occupying forces – first the Soviets and then the Germans – it became a universal symbol both of Soviet deportations and of German transports of people displaced from territories incorporated into the Reich or destined for forced labour, concentration camps, or death camps. The freight wagon, which is so often present in exhibitions on the Second World War, acquires a broader importance here.

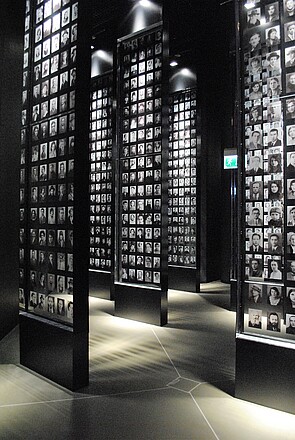

The purpose of the objects featured is to offer multiple perspectives on particular events and phenomena. A special place has been assigned to objects associated with specific people, which are presented in separate, uniformly designed spaces. In some cases, the chosen characters are persons who played a special role during the war; in other cases, they exemplify the fate of millions of other people. German and American documentarians and filmmakers such as Leni Riefenstahl and Julien Bryan also have sections devoted to them. Separate spaces are dedicated to ordinary people, such as Zdzisław Wysocki, who was among the hundreds killed when Polish refugee columns were attacked in 1939, as well as to outstanding characters such as Bent Faurschou Hviid, one of the most famous members of the Danish resistance movement. The choice of characters and of the objects associated with them is based on a conscious selection of different perspectives: those of the perpetrators, the victims, and of the observers of wartime events.

The museum exhibits are supplemented by iconography consisting mainly of reproductions of photographs, often in the form of large-format prints. In principle, the photographs have been selected according to the same criteria as the objects. Here, however, it is evident that images containing the most dramatic scenes have generally been chosen.

As regards the number of photographs and exhibits on display, the right proportions have been maintained – enough room has been left for visitors to notice them and to understand the central role that they play in the narrative. Only occasionally does one encounter objects that appear to illustrate a given subject in overly general terms. One example is the quern-stones from a Ukrainian village that were used by peasants in the 1930s to grind grain for bread-making. In the period in question, the communists destroyed quern-stones, condemning civilians to death as a result. Obviously, the item fits the theme of the exhibition, but it could equally be replaced with any other object from that time and place. The same accusation could be made about the sledge from Leningrad, for instance. Similar sledges were used to transport water, wood, and corpses in the besieged city. It is not clear, however, whether the particular sledge exhibited here was ever used for such purposes. Many ordinary objects of this kind – anonymous witnesses of the events described – are featured in the exhibition. They are used primarily where it was difficult to link an object’s personal story with the subject in question.

To most visitors, objects and photographs would be hard to comprehend without a description and context. These are provided by the texts and descriptions which are a definite strong point of the exhibition. They are clearly differentiated so that visitors know intuitively which ones introduce a section or subject and which ones include biographies or object descriptions. Care has also been taken to ensure that the labels are not overly long. Typically, a single label does not exceed a few hundred characters, which makes it appear concise and inviting for visitors. This is important because the exhibition is huge. The authors have thus tried not to discourage visitors at any point and to maintain their interest throughout. However, the texts deserve praise not just for their brevity but also for their high quality. Of course, the quality of the content is often governed by the objects themselves or, rather, by the stories associated with them. The authors of the exhibition have ensured that the descriptions are interesting and dynamic; separate, smaller stories are also often embedded within them.

The multimedia solutions, which are ubiquitous throughout the exhibition, primarily comprise stands with screens that present the given subject in greater detail. A single stand usually offers several additional interrelated themes, which are concisely and coherently presented; this approach, far from causing visitor fatigue, does just the opposite: it encourages visitors to look at more stands and explore their contents. The stands also represent the main interactive element of the exhibition. This principally means that visitors choose the themes they want to learn more about – the curators have provided only a few other possibilities for interacting with the presented content. These include a multimedia quiz in which visitors compete against each other in answering questions about living conditions in occupied Europe. Another example is the possibility to encode and decode a message of one’s choosing in the space devoted to the Enigma cypher machine. As for physical interaction, visitors can try their luck at lifting an object whose weight corresponds to that of the equipment typically carried by a front-line soldier. Fortunately, unlike at some other similarly-themed museums, visitors are not invited to impersonate soldiers or handle dummy weapons.

A surprising oversight, however, is the absence of stimulating interactive content in the part of the exhibition designed for children. That the latter has been excluded from the main narrative and constitutes an additional component of the exhibition seems to be the right solution. The exhibition for children consists of two parts: the first is a reconstructed classroom from the inter-war period in Poland. Seated on classroom benches, visitors are shown a long multimedia presentation about the life of young people during the inter-war years. The second part comprises the reconstructed interiors of homes dating from three periods – September 1939, 1943, and just after the end of hostilities. As they enter each room, visitors can see the changes in living conditions and hear the voices of two children recounting what life was like from their point of view. Apart from listening to the children’s very long accounts and viewing the interiors and the reconstructed animated views outside the windows, there is little else to be done in these spaces. The section for children, which was perhaps designed with educational activities in mind, is the weakest element of the exhibition space.

On the other hand, the films featured in the exhibition are its strength. Nearly all the short documentaries include an excellent selection of images and are very well edited, their quality reflecting the filmmakers’ dedication. The films’ subjects have also been selected in such a way as to broaden viewers’ knowledge of compelling themes; interesting juxtapositions are used as well. The exhibition also includes many filmed accounts of people who witnessed the war first-hand; unfortunately, the quality of these is not as good. The eyewitness accounts are often too long and monotonous; it is also regrettable that in some cases a Polish voice-over has been used instead of subtitles.

Another element of the exhibition worth mentioning is the sound content. Undoubtedly, aside from the spaces constructed as theatrical sets meant to represent a school, street, or destroyed city, music is the part of the message that has the greatest emotional impact. Music is used liberally in the exhibition’s initial phase – e.g. Wagner accompanies the Nazis’ rise to power in Germany, Soviet troops enter Poland against a backdrop of military marches, and in the space dedicated to the siege of Leningrad visitors listen to Shostakovich’s Leningrad Symphony. However, when the narrative shifts to the tragedy of war and human suffering, the mood is no longer shaped by music. Until the end of the war narrative, the exhibition remains silent; music is only be heard again after peace has returned. The authors of the exhibition rightly decided that visitors should encounter its most important section in silence and intellectually grasp the objects and the associated stories without any additional emotional tension being introduced by dramatic or moving music (as in the space devoted to the death of prisoners of war in German captivity).

Another component of the sound content is the audio guide, available in five language versions: Polish, English, French, German, and Russian. As with the object descriptions and multimedia offerings, the content of the audio guide has been carefully prepared and the recordings are not so long as to cause visitor fatigue. There are a few problems, though. For instance, individual recordings cannot always be launched automatically and there is limited control over playback.

An important aspect of the exhibition is that it coexists with the place in which it is located. It is no accident that visitors are introduced to the events that preceded the conflict in Europe in the room dedicated to the Free City of Danzig, while the main part of the exhibition (“The terror of war”) begins with the story of German aggression against Westerplatte, which was part of the Free City.

Similarly, the war narrative ends in Gdańsk. This time, the Germans are fleeing and the Soviets are entering the city, which has become a scene of destruction, looting, and rape.

The story of the war is present not only in the exhibition’s narrative but also in the very location and design of the museum building. The museum stands a mere 250 metres away from one of the first points of resistance on 1 September 1939 – the Polish Post Office in Danzig; it is also located in a section of the city that was annihilated in the final days of the war. This is obvious to visitors when they observe the empty space around the museum and also when they enter the exhibition itself – its axis, the corridor from which the various parts are accessed, runs exactly along the line of the no longer extant Große Gasse, the district’s main street. Thanks to the exhibition’s layout, the street has been “reconstructed” (in an altered form) several metres underground, but above all it has been restored to memory, erased by the wartime conflagration.

It would seem that a Museum of the Second World War could have been built in hundreds of places around the world, but the local history of Gdańsk and Pomerania, which is emphasised in the exhibition, makes the case for establishing such an institution precisely here. The form of the exhibition and indeed of the building itself confirms this choice and renders it consistent with the story presented.

Many criteria can be used to determine whether a narrative exhibition is a success. An important one is whether the initial goals have been achieved. Let us recall that the authors set out to tell visitors about the enormous cataclysm of the Second World War and the immense suffering it caused to millions of people, about the Polish perspective and Poland’s role in that conflict, and also about the universal concept of evil that accompanies each and every war.

To a large extent, the exhibition has accomplished these goals. Its pacifist message is manifest in the content and in the selection of exhibits and photographs; it is also evident in almost every human story featured, but also explicitly stated in connection with certain topics. In the space that describes hostilities in the first years of the war, visitors listen to letters from the front written by soldiers of different nationalities to their families. Although penned in different languages, the content of these letters can often be encapsulated by the blunt question posed by Walther Schmidt, a private in the Wehrmacht: “What is the point of all this?”.

From the outset, the story told by the exhibition attributes the responsibility for the whole tragedy of the war explicitly to Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. However, there is also a general message, namely, that evil has no nationality and that war usually brings out the worst in people. Thus, the exhibition also addresses the issue of German and Russian victims of the war, for example, in an installation that fills an entire room and is dedicated to the more than three million Soviet prisoners of war who died in German captivity. Even the actions of the Warsaw Uprising’s fighters, whose suppression by the Nazis led to the complete destruction of the Polish capital, are summarised with a quote from one of the combatants describing the people of Warsaw: “They scowl at us because it is we, the insurgents, who have brought this misery upon them.” All sides in a conflict have their share of evil and suffering.

The ultimate message is therefore quite pessimistic. The visitor leaves the exhibition with the thought that the Second World War destroyed an entire world and millions of lives, yet we still have not learned any lessons from it. Thus, the final part of the exhibition concerns a world that remains divided and conflicted, with new wars beginning even after the fall of the Iron Curtain. The video installation showing a divided image (resembling the world divided by the Iron Curtain), followed by an undivided image of the ongoing wars in Ukraine and Syria, leaves one with a somewhat bitter reflection on the past and present condition of humanity. Visitors leave the exhibition to the sound of House of the Rising Sun by The Animals, which completes the idea that we are bound to return to our point of departure, despite being aware of the evil that lies therein.

If, like the authors of this exhibition, the visitor believes that all violence is evil and only gives rise to further suffering, he or she will feel perfectly attuned to the message contained in the permanent exhibition of the Museum of the Second World War. If, on the other hand, he or she has a different system of values, the message may ultimately not get through, and the entire narrative will prove annoying.

The Gdańsk exhibition presents a long narrative, but one that is dynamic and diverse in both content and form. It is a story that may prove convincing and comprehensible to a wide range of visitors: those who have encountered the subject of the Second World War for the first time; those who only know it from the western or eastern perspective; and finally those who are tired of the war being portrayed as merely a series of military campaigns. The engaged narrative at the end of the exhibition shows us that the story is not just about those who witnessed the war years, but also about ourselves.

I consider this universal message, which is evident both in the small stories presented and in the narrative as a whole, to be an excellent approach. It is an approach which, together with the many other elements included in this new narrative about the war, has the potential to significantly change our thinking about a subject that at first glance appears obvious. In my view, this is one of the most important characteristics not just of a well-designed exhibition, but of any story in general. Despite a few shortcomings, which – it must be admitted – are very difficult to avoid in such a huge undertaking, the permanent exhibition of the Museum of the Second World War is on par with other great museum narratives worldwide. It provides, literally and symbolically, the foundation for the Museum that operates several floors above it. Let us hope that its future activities will live up to the quality of the project whose culmination was the permanent exhibition that opened this year.

Translated by Jasper Tilbury

Andrzej Hoja: An Engaged Narrative: the Permanent Exhibition of the Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk. In: Cultures of History Forum (24.07.2017), DOI: 10.25626/0065.

Copyright (c) 2017 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

See a recent interview (in Polish) with the former director of the Museum, Prof. Paweł Machcewicz, about the current situation and future of the exhibition.

See also previous contributions about the museum in the Cultures of History Forum by Florian Peters (3 October 2016) und Daniel Logemann (21 March 2017)

Lidia Zessin-Jurek · 20.04.2023

A History that Connects and Divides: Ukrainian Refugees and Poland in the Face of Russia’s War

Read more

Lidia Zessin-Jurek · 20.12.2021

Trapped in No Man’s Land: Comparing Refugee Crises in the Past and Present

Read more

Interview · 08.03.2021

A Ruling Against Survivors – Aleksandra Gliszczyńska-Grabias about the Trial of Two Polish Holocaust...

Read more

Lidia Zessin-Jurek · 03.09.2019

Hide and Seek with History – Holocaust Teaching at Polish Schools

Read more

Maciej Czerwiński · 11.04.2019

Architecture in the Service of the Nation: The Exhibition ‘Architecture of Independence in Central E...

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).