03. Sep 2018 - DOI 10.25626/0088

Dr Valentin Behr holds a PhD in political science and is associate researcher at the SAGE Laboratory (CNRS and University of Strasbourg). His PhD dissertation was dedicated to a socio-historical analysis of the Polish historiography about the 1939-1989 period. It shows how Polish historians of different generations and under changing regimes have been dealing with political constraints in their work. His main research interests include the sociology of knowledge and ideas, historical policy, historiography of Communism and the Holocaust in Poland, as well as sociology of elites. You can find information on his recent publications and activities here.

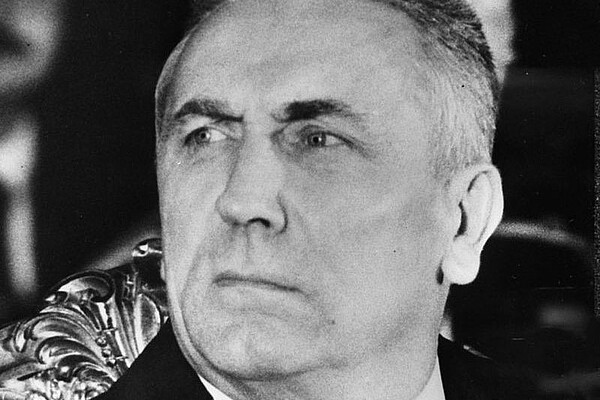

In Poland, since the Law and Justice (PiS) party’s return to power in 2015, political uses of the past have become a major political issue.[1] The so-called ‘historical policy’ has made a comeback as a centrepiece of PiS’s political agenda, articulated in several areas of public policy, including culture, education, science and foreign affairs. In this context, controversies have flared up, for example, in connection with the Museum of the Second World War in Gdansk, where the PiS government successfully manoeuvred the ouster of the Museum’s first director and forced changes to the original exhibition.[2] In question is the master narrative that the Polish state wishes to offer visitors of the Museum: Should the painful history of Poland in the twentieth century be presented in black and white – placing the emphasis on victimization and national heroism – or is it possible to look for more balanced, reflective, and critical narratives? One possible way to explore Polish history might be to focus on historical figures whose personal behaviour and life trajectories through the twentieth century are not easily judged on moral terms. According to its short introductory trailer, this was the goal of the exhibition Edward Gierek – Między Wschodem a Zachodem (Edward Gierek – between East and West), which ran for less than two months, from 8 March to 29 April, 2018, and was organized and displayed by the Pałac Schoena Museum in Sosnowiec (in today’s Upper Silesian voivodeship). Edward Gierek (1913-2001) was the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR) from 1970 to 1980. The exhibition not only focused on his years in power during the so-called “Gierek decade” but tells a longer story: By way of the story of a man, born in Upper Silesia in 1913, who emigrated to France and Belgium during the interwar period to work as a miner, before becoming one of the most prominent figures in the Polish People’s Republic (1944-1989), the exhibition offered a careful and balanced narrative of Communist Poland, from a distinctly local perspective. Nonetheless, this perspective could not be completely detached from the current political context.

The conception of the exhibition, which was housed in a municipal museum in the city of Gierek’s birth, Sosnowiec (near Katowice), was closely linked to the ‘decommunization law’, passed by the Polish government in April 2016. The law prohibited the "propagation of Communism or any other totalitarian regime" in public spaces, and required local authorities to remove any references to Polish communists, Soviet soldiers, or Polish troops who served alongside the Red Army from public spaces, including from statues, monuments, buildings and street names. In cases where local authorities did not comply by September 2017, the voivode (i.e. the governor of a Polish administrative region, a voivodeship) could step in to rename the sites in question.[3]

In response to the law, the city of Sosnowiec was obliged to change the name of one of its major roundabouts, named after Edward Gierek, as the former First Secretary of the PZPR was among those Polish communists who were supposed to disappear from the public sphere, according to a blacklist prepared by the Polish Institute of National Remembrance (IPN). Yet, the former Communist leader, who died in 2001, remains very popular in his birth city and region, where his name is still associated both with the economic development of the region during his leadership of the Silesian PZPR, and with the rather smooth decade between 1970 and 1980 during which he led the country on the national level. Indeed, the Gierek decade corresponds to a period of significant change within Polish society, with a relative improvement in quality of life, under the slogan of "catching up with the West", and a decline in political repression, as compared to earlier periods. For these reasons, Gierek’s name is still associated with a form of nostalgia for the Polish People’s Republic among the inhabitants of Sosnowiec and of Upper Silesia more broadly. This enduring popularity is also reflected in the political success enjoyed by his son, Adam Gierek, who was elected to the European parliament in 2004, representing Upper Silesia under the banner of the left-wing Labour Union (Unia Pracy), at a time (especially since the mid-2000s) when the left has progressively disappeared from the Polish political scene.

The mayor of Sosnowiec, a member of the Liberal Civic Platform (PO), opposed the decision of the voivode to change the name of Gierek roundabout into "Dąbrowa Basin roundabout" (rondo Zagłębia Dąbrowskiego). He even organized a local consultation with residents on the matter. Despite its purely consultative character, the results of this consultation were striking: Ninety-seven per cent of voters opposed the renaming of the roundabout.[4] Thus encouraged, the mayor asked the director of the Palac Schoena Museum in Sosnowiec to curate an exhibition dedicated to Edward Gierek’s life and achievements. Given that the exhibition originated in the midst of such a political conflict, it could easily have become just one more example of an instrumentalization of the past. Nonetheless, the curators managed to create an exhibition that provided a well-balanced narrative, inviting visitors to engage in self-directed reflection rather than pushing for a univocal interpretation.

The exhibition took place in the Pałac Schoena municipal museum in Sosnowiec, located in a Neo-Baroque palace, built in the late nineteenth century by a factory owning family. The museum consists of four thematic sections: arts, glass (the museum hosts one of Poland’s most important collections dedicated to glass-making), archaeology, and history and culture of the city. It is the latter unit, which hosts documentation on the local history of Sosnowiec and the Dąbrowa Basin region, which oversaw the curation of the Gierek exhibition.

It is important to note here that the project was rather hastily put together, as it was not part of the Museum management’s longer-term planning. Due to political demands, the curators had barely two months to design the exhibition, and consequently, it was based on rather limited resources and documentation. Nevertheless, the curators could rely on a number of partners, such as the local branch of the Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) in Katowice, the family archives of the Gierek family, and collections from other museums: the Museum of the Polish People’s Republic in Krakow, the Historical Museum of the City of Krakow and the Museum of History of Katowice, all of whom provided extensive support in the form of pictures and items, completing the Pałac Schoena Museum’s own collections. Nonetheless, the museum’s management refused invite other institutions as patrons for the exhibition, a move motivated by the specific political context. According to the museum’s director, Paweł Dusza, "left-wing as well as right-wing organisations called me with many questions about the exhibit. I consciously made the decision that there will be no patronage for the exhibition. I take full responsibility for it."[5]

Besides the museum’s director, the local branch of the IPN in Katowice refused to be officially associated with the organization of the exhibition, as the Institute plays a major role in the implementation of the ‘decommunization law’, by providing historical expertise to identify those sites which require renaming.

Both the curators and the director of the museum underlined their desire to design an exhibition that would show both positive and negative aspects of Gierek’s achievements, the complexity of his character, and of his career. This determination led to the adoption of an extended chronology for the exhibition, which presented not only the public and political life of Gierek, but began with his birth in Sosnowiec, the experience of poverty and emigration before his return to Poland in 1948, his political career within the Party, from the Voivodeship (regional) Committee to the Central (national) Committee and the office of First Secretary, his imprisonment under Martial Law (1981-1982) and, finally, his burial in Sosnowiec, attended by approximately ten thousand people. The whole exhibition intertwined Gierek’s biography, the local history of Sosnowiec and the Upper Silesian region, with national and even global history. In each room, information panels recalled the broader political and regional context: Stalinization and de-Stalinization, the events of 1968 in Warsaw and Prague, the December 1970 strikes on the Baltic coast, the rise of the Solidarity movement following the Gdansk agreements of 1980, and the introduction of Martial Law in Poland (1981-1983). At the end of the exhibit, a timeline of Gierek’s biography hung on the wall in front of a road, connecting Sosnowiec with Warsaw, which was symbolically painted on to the floor and decorated with vintage motorcycles.

More specifically, the exhibition encompassed five rooms, each one representing in chronological order a stage of Gierek’s life. Before entering the first room, quotations painted on the walls established the underlying tone to the exhibition: the phrase ‘Socialism with a human face’, widely associated with the Gierek decade, was highlighted, followed by a quotation from a recent popular biography entitled Gierek. Man of Coal, which recalled that Poland in the 1970s was associated with spending holidays in Yugoslavia at the Adriatic Sea, importing Bulgarian wine, listening concerts by Western bands broadcast on television, and watching American movies in Polish cinemas.[6]

Beyond the exhibited pictures and objects, each room offered an information panel with texts and quotations summarizing the historical context and Zeitgeist of each period. The first room, titled Rozgoryczenie (Bitterness), presented Gierek’s youth in the impoverished city of Sosnowiec during the interwar years. It was mainly made up of family souvenirs, including Gierek’s own traditional Silesian miner’s suit, lent to the museum by his son Adam. Unfortunately, time constraints prevented the curators from collecting materials on Gierek’s emigration to France and Belgium, where he was already active in the Communist movement. Emigration was therefore symbolized by Gierek’s old suitcase, also provided by the family. An information panel displayed a quotation from one of Gierek’s biographies: "The future First Secretary spent his childhood and youth in France and Belgium, as it was difficult to get a job in his homeland at that time. He knew what poverty and joblessness were."[7] The curators thus emphasized a feature which has often been described as a key to Gierek’s popularity: his working-class background and his own experience of hard work as a miner, in contrast to the social background of many other Party apparatchiks. Additionally, a panel described the extreme poverty of some districts of Sosnowiec during the interwar period in order to explain why many families emigrated at that time. It also indicated that new blocks of flats were built in those districts after the war, thereby explaining how speedy socio-economic change might have attracted working-class Poles to the new regime.

The next room (Uwiedzenie, Seduction) was dedicated to Stalinist Poland. It revealed the repression of that time, emphasizing the persecutions through a reconstructed prison cell, while also reflecting on the rebirth of Poland after the Second World War, as well as on the first socialist-style construction projects, such as the building of Nowa Huta, the huge ironworks near Cracow. Stalinist Terror was certainly mentioned but remained secondary to the reconstruction of the country after the War. This stands in contrast to the dominant narrative in Polish historiography which is focused on terror and repression. Although Gierek was not among the prominent Party leaders at that time, a picture from the IPN’s collection shows him standing next to Jozef Cyrankiewicz, then Prime Minister, at the burial of Communist victims of the 1956 protests in Poznań. Gierek was indeed a member of the Commission investigating the events of Poznań, which provided a deceitful narrative, according to which provocateurs and foreign agents attacked the police.

The third room displayed Gierek’s "Path to the Top" (W drodze na szczyt), highlighting his achievements in the voivodeship of Katowice, where he was First Secretary of the Voivodeship Committee of the Party, from 1957 onwards. This period, which ran until Gierek’s designation as First Secretary of the Party in 1970, was described as a moment of reconstruction and expansion in Katowice and Sosnowiec, illustrated with pictures of the construction of the famous Spodek (saucer), a UFO-style multipurpose arena complex designed to host sporting and cultural events, and is still one of Katowice’s main attractions. This was the period during which Gierek became well-known across the entire country as a leader from a region that was seen as a symbol of economic performance in Communist Poland. Once again, the curators counterbalanced these achievements with stories of local repression during the social protests of 1956, 1968 and 1970. State repression was depicted by means of particular items such as the metal chain used to lock the doors of a Sosnowiec church in order to prevent Stefan Wyszyński, the Polish primate, and Karol Wojtyła (elected to the papacy as John Paul II in 1978) from celebrating Mass for the Polish millennium in 1966.

The penultimate room, entitled Szczyt (the Top), was also the biggest one – almost twice as large as the others – and was dedicated to the so called “Gierek decade” from 1970 and 1980. It presented the expansion of Poland’s economy (thanks in large part to foreign credits), the opening of the country to the world, the relative loosening of internal politics as well as the decline in political repression. Poland’s opening to the West was illustrated by photographs of meetings between Gierek and Western heads of state, including Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, Helmut Schmidt and Richard Nixon. Here too, the curators connected national history with local history. One exhibit panel was dedicated to the erection of "Huta Katowice" (Katowice Ironworks) and read,

From the very beginning, everyone looked after the fate of this giant building, which became one of the symbols of Edward Gierek’s era. The best things in the country (machinery, devices, builders, engineers) were in the Dabrowa basin.

In addition, the panel underlined the foreign provenance of much of the equipment of the Katowice ironworks, which came from the United States, France and Sweden – "not only from the Soviet Union." This section of the exhibit also reconstructed the Politburo conference room, alongside a screen that played extracts from Gierek’s most famous speeches. Fragments of those speeches were also showcased on information panels, in particular his address at the Gdansk shipyard in 1971: "If you help us, I believe that we will manage to achieve this target… so what? Will you help? (Applause)… Well." Other statements from Gierek underlined his will to build a “second Poland”, in which people would live "prosperously". The resonance of such quotations is very positive, especially when compared to statements displayed earlier in the exhibition from other Polish Communist leaders, which underline the political repression of the state. Thus, Władysław Gomułka was quoted earlier with a statement from 1945: “We will never give back the acquired power. You can shout that the blood of the Polish people is pouring, […] it will not make us turn back.”

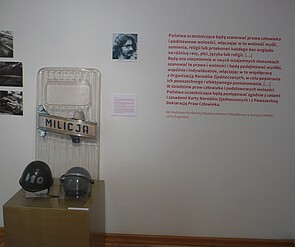

Here too, the exhibition curators sought to balance the positive depiction of Gierek with the more negative aspects of that time, addressing, for example, the question of shortages (of goods and foodstuffs) in the context of increasing economic crisis. An information panel described the “ticket-system” and the inability of the Soviet-style economy to provide basic necessities, since tickets were required to acquire sugar or coal, followed by a recollection of the defeat of worker’s strikes in 1976, as they protested price increases on necessary goods. Political repression was also portrayed through a portrait of student leader Stanisław Pyjas, believed to have been murdered by the Security Services in 1977. To underline the contradictions of the Polish Communist regime on the issue of human rights, Pyjas’ portrait was displayed next to the shield and helmet of a member of the “Citizens’ Militia” (Milicja Obywatelska), and the text of the Helsinki Accords, which was signed in 1975 by countries from both sides of the Iron Curtain, including Poland, and guaranteed civil and human rights for all. The Gierek decade ended with the rise of the Solidarity movement following the strikes in the Gdansk shipyards, after which the First Secretary was replaced by Stanisław Kania.

Finally, the last room, Upokorzenie (humiliation), presented the fate of Gierek after 1980, including his imprisonment under Martial Law, the fall of the Communist regime as a result of the semi-free elections of 1989, and Gierek’s eventual retirement. The contentiousness of his memory in post-communist Poland was addressed in a 40-minute long documentary film, through the testimony of various witnesses, including former Party comrades and dissidents, but also the expert assessment of several historians and journalists. It also included an interview with the retired First Secretary himself, conducted in 1996. Interestingly, the film actively reminded visitors of the current controversies around Gierek’s legacy. In fact, Polish public television decided to put together this film after multiple grassroots projects aimed at honouring Gierek’s memory emerged in the early 2000s, including the re-naming of squares and streets in his honour. The film includes interviews with the supporters of the such initiatives, mainly industrial workers – confronted with the growing unemployment which followed the reorganization of the Polish economy after 1989 – who spoke with nostalgia of the Gierek decade, which they associated with greater prosperity.

Visitors exited the exhibition via a room furnished as a typical working-class apartment from the 1970s, which also screened extracts from TV news broadcast by Polish television during the Gierek decade. One of those clips depicted the inauguration of Warsaw’s central railway station in 1975, emphasising the modernity of the building – especially its automatic doors –which at that time attracted the curiosity of visitors. Finally, at the very end of the exhibition, after passing through the timeline mentioned above, the visitor was offered an opportunity to evaluate Gierek’s achievements positively or negatively, by placing a ball in one of two urns, marked “+” and “-”.

Even though the Gierek exhibition was designed in response to a request from Sosnowiec’s mayor in reaction to the decommunization policy, the curators managed to deliver an astute narrative, continuously balancing the positive and negative aspects of Gierek’s political project, thereby inviting visitors to independently reflect on Gierek’s life. This aim was also echoed in two speeches given at the exhibition’s opening in March 2018, delivered by Sosnowiec’s mayor Arkadiusz Chęciński and the museum’s director Paweł Dusza:

The exhibition shows Edward Gierek as someone who did a lot for our country. He opened our country to the West. He built many workshops, factories and roads. We also want to show the other, darker, side. Under the Polish People’s Republic many people had a hard life and tragic events took place. We want to show the true life of a man, an inhabitant of our city. (Arkadiusz Chęciński).

The narrative of this exhibition will be readable and full of contrasts. Such were the times of Gierek. Edward Gierek himself was a character full of contrasts. A man who believed in Communism in Poland but was badly treated by the regime at the end. (Paweł Dusza)[8]

Indeed, Gierek became a scapegoat for the PZPR’s elite at the beginning of the 1980s.[9] Held responsible for the economic crisis of the late 1970s, he was among the very few top Communist leaders to be jailed under Martial Law (1981-1983), which was instituted in order to crush the democratic opposition by arresting the leaders of the Solidarity trade union. Along with accusations of corruption, this did not diminish Gierek’s popularity.

It is important to keep in mind the specificities of the local context in Sosnowiec and, more broadly, in today’s Upper Silesia. Local collective memory remains keen on Gierek’s legacy, as can be seen by the response at the consultation with Sosnowiec residents as they overwhelmingly opposed the renaming of the Gierek roundabout. Furthermore, the exhibition reached a large audience: in an interview with the author, Paweł Dusza claimed that more than 400 people had attended the inauguration, and 2 355 people had visited the exhibition, which lasted less than two months – a number above the average for the Pałac Schoena Museum in Sosnowiec. According to the curators, most visitors, unsurprisingly evaluated the Gierek decade positively by putting a ball in the “+” urn at the end of the exhibition. Nevertheless, Dusza strongly underlined his desire to offer a balanced exhibition and to let visitors make their own judgment about the past.[10]

In order for visitors to engage in independent reflection, the curators attempted to intertwine political history with social and economic history, two dimensions of recent Polish history which are often separated in the historiography.[11] Most existing exhibitions dedicated to Communist Poland generally overemphasize political events. By giving greater importance to daily life, the goal was to reconstruct the atmosphere of the 1970s and 1980s, in order to allow visitors to identify with ordinary citizens in the Polish People’s Republic. For those too young to have experienced this period themselves, it was possible to encounter a typical working-class apartment, while older visitors could recall with some nostalgia the ‘Pewex’ shops, which offered Western goods in exchange for Western currency. According to Dusza, each visitor was free to formulate their own opinion by retaining whatever they wanted, Terror or the more positive aspects.[12] Nonetheless, even if some residents expressed their disapproval of the planned exhibition, there is no doubt that such exhibition would have been forcefully criticized elsewhere in Poland, given the current anti-communist atmosphere.

That atmosphere is recalled at the very end of the exhibition, as the displayed timeline ends in the present, with two cheeky references to the current political context. The first reference is a quotation from Law and Justice (PiS) party chairman, Jarosław Kaczynski, who declared in an electoral event in Sosnowiec in 2010 that Gierek was “a Communist, but also a patriot”; the second recalls the result of the local consultation when Sosnowiec’s residents opposed the renaming of the Gierek roundabout in response to the decommunization law passed by the same party in 2016. In a note by the Polish Institute of National Remembrance explaining why the person of Edward Gierek falls under the decommunization law, Gierek is described as a politician who favoured the interests of the Communist party and the Soviet Union, since it was in 1976, under his leadership, that the Constitution of the Polish People’s Republic was changed to introduce an amendment on the leading role of the PZPR and its alliance with the USSR. The IPN underlines the myth of Gierek as “father of the nation” is a product of Communist propaganda. For supporters of the anti-communist mainstream, the exhibition “Edward Gierek. Between East and West” at the Pałac Schoena Museum in Sosnowiec can certainly be understood as an act of nostalgia for the former Communist leader. One could also argue that the curators’ desire to offer a balanced narrative and to let visitors make up their own minds encourages relativism. I would rather argue that such an exhibit provides a smart narrative that allows viewer to go beyond anti-communist dogma and take note of the competing social frames of memory within Polish society.[13]

The academic mainstream since 1989 has assessed the Gierek decade negatively, underlining the economic crisis that struck Poland in the second half of the decade, the oppression of political opposition and Poland’s increased servility towards the USSR. Official state historical policy takes this narrative even further. The radicalization of the historical debate and the decommunization laws introduced by the PiS government threaten not only regional forms of Gierek commemoration, but also a more moderate evaluation of this complicated period. This is best testified by the fact that the Sosnowiec local police, commissioned by the district prosecutor’s office, started to investigate whether the exhibition was “propagating Communism”.[14] Thus, the exhibition in Sosnowiec, which presented a balanced picture of the 1970s, is both of historical and contemporary relevance for East Central Europe, as it tackled the clash between popular memory and scholarship, between official historical policy and contemporary assessments of the Communist period.

Valentin Behr: When Local Memory Confronts State Historical Policy: Staging Edward Gierek’s Life in Sosnowiec. In: Cultures of History Forum (02.09.2018), DOI: 10.25626/0088

Copyright (c) 2018 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

Lidia Zessin-Jurek · 20.04.2023

A History that Connects and Divides: Ukrainian Refugees and Poland in the Face of Russia’s War

Read more

Lidia Zessin-Jurek · 20.12.2021

Trapped in No Man’s Land: Comparing Refugee Crises in the Past and Present

Read more

Interview · 08.03.2021

A Ruling Against Survivors – Aleksandra Gliszczyńska-Grabias about the Trial of Two Polish Holocaust...

Read more

Lidia Zessin-Jurek · 03.09.2019

Hide and Seek with History – Holocaust Teaching at Polish Schools

Read more

Maciej Czerwiński · 11.04.2019

Architecture in the Service of the Nation: The Exhibition ‘Architecture of Independence in Central E...

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).