12. Jan 2018 - DOI 10.25626/0089

Dr. Zuzanna Bogumił is Assistant Professor at the Maria Grzegorzewska Pedagogical University in Warsaw. Her research to date has dealt with Russian memory of twentieth-century Soviet repressions, as well as the symbolic meanings of historical exhibitions in Central and Eastern Europe. She is currently coordinating two projects on the religious dimension of memory: “From Enemy to Martyr” http://www.memoryofrepressions.aps.edu.pl/?participants and “Milieux de Mémoire in Central and Eastern Europe – a Polish case” www.milieuxdememoire.aps.edu.pl. She is the author of Pamięć Gułagu (Gulag Memory, (2012) forthcoming in English with Berghahn Books in 2018, and the co-author of Enemy on Display: The Second World War in Eastern European Museums (2015).

Father Jerzy Popiełuszko was a Polish Roman Catholic priest associated with the Solidarity movement, who became a symbol of the Polish struggle for liberty during the communist period. He was murdered in 1984 by agents of the Polish Security Service. The officers bound a stone to his feet and drowned him in the Vistula Water Reservoir near Włocławek. His murder led to social upheaval. His funeral, attended by some 800,000 people, including representatives of the Solidarity movement led by Lech Walesa, turned into a great political demonstration which was widely broadcast by media all over the world. Shortly after his death, Father Popiełuszko was recognised as a martyr by the Roman Catholic Church. However, he was only beatified in 2010. A year before, in 2009, he had been posthumously awarded Poland’s highest state distinction, the Order of the White Eagle.

On the occasion of Father Popiełuszko’s beatification, Sophia Deboick wrote in The Guardian: “His example shows us that saints who were political dissenters, inspired as much by love of their country and of justice as by love of God, can transcend boundaries between the religious and secular.”[1] Indeed, Jerzy Popiełuszko is perceived both, as a national freedom fighter and a Catholic martyr. He was not executed for his religious beliefs, Deboick continues, but “for his political dissidence, and as such he offers a focus for remembrance of all who have courageously defied authoritarian regimes.” Father Popiełuszko was “acting on the basis of universal principles of freedom and human rights”, and his “commitment to those principles and the magnitude of their bravery exercises a power over us all.”[2] Such views may explain why Father Popiełuszko is so widely embraced as a point of reference by various memory actors to frame their particular memory projects. The Roman Catholic Church itself uses him to achieve objectives far beyond the narrow remit of the Catholic cult. The Blessed Jerzy Popiełuszko Museum in Warsaw represents one example of such practice.

In this article, I shall analyse the exhibition of the Blessed Jerzy Popiełuszko Museum in Warsaw to consider what kind of narrative of the life and death of Father Popiełuszko it proposes. In Poland, Father Popiełuszko is perceived as both a national hero and a Catholic martyr, but how is he cast in a church museum? What kind of message (religious, secular, universal) does the museum attempt to transmit? In this article I am also interested in grasping the perspective of the museum’s founders, who do not conceal their views and religious beliefs, and in describing the meanings they assign to the exhibition.[3] Thus, I consider the museum from a post-secular perspective, and try to establish whether this museum, created in the framework of Christian beliefs, may have an impact on visitors who are non-believers.[4]

The Blessed Jerzy Popiełuszko Museum in Warsaw is not the only multimedia display dedicated to Rev. Popiełuszko in Poland. In the northwest of Poland, there are two very modern exhibitions located at the sites of his martyrdom: in the village of Górsk, where he was kidnapped and where the first drop of his blood was shed, and in the town of Włocławek, near the dam where his body was thrown into the river. But these are not all the museums. The Roman Catholic Church in Poland has been developing more and more museums and multimedia exhibitions. This new phenomenon can be interpreted in light of the Church’s desire to have an impact on people; thus it has resorted to such means as attract and appeal to visitors. The new church museums can be viewed within the context of popular culture’s influence on contemporary religiosity, but they can also be understood as a manifestation of the Church’s desire to participate in cultural development. As Roger Kimball stresses,

[a]t one time in the West, that node of interest centred around the Church, at another the palace, at another the town square […]. In our culture, there is a good argument to be made that for some time now the apogee of architectural ambition has centred around the museum.[5]

This focus on museums means that the Church, too, is constructing modern multimedia spaces similar to those found in other contemporary historical museums. These Church-sponsored spaces follow the same principles, employ the same means and techniques, and are often conceptualised by the same professional design companies. But can they really be perceived to be part of the same phenomenon? Susan Sontag claimed that contemporary Holocaust museums reflect a particular way of thinking about murdered European Jews.[6] Thus, what kind of thinking about twentieth-century crimes does the Blessed Jerzy Popiełuszko Museum in Warsaw propose?

Valerie Casey uses Lacan’s concept of the Gaze to explain the evolution of the museum.[7] According to Lacan, there is no pure relationship between a subject and an object; this relationship is always mediated by a “screen”, which is merely an image of the object and not the object itself. In the case of the museum, as Casey claims, the screen may be understood literally as the curatorial information, or in abstract terms, as the desire linked to the unattainable object which motivates intellectual and aesthetic pursuit. Casey contends that the relationship between the object and the subject evolves and is evaluated over time, which provokes changing modes of museum practice.

This evolution consists of nothing more than the museum becoming increasingly performative. Until the nineteenth century, Casey claims, the legislating museum was dominant. This museum deployed authority through objects, not information; thus it created a specific experience of the object. After the Second World War, pedagogically focused museums appeared which represented the interpreting type of museum. Through label text and multimedia tools, the museum provided a framework for how objects should be viewed and understood. As museums moved away from using objects as the primary vehicle for conveying information, the importance of display increased. As a result, contemporary living-history museums are classified as performing. Performance extends beyond the employment of interactive tools and multimedia technologies to engage the visitor; there are also re-enactments and recreations which help the museum convey its message. As a result, the objects are no longer important, in fact they might even be absent, because the narrative and the experience of the narrative are now at the centre.[8]

The Blessed Jerzy Popiełuszko Museum seems to be an interesting combination of all three museum types identified by Casey. It takes the narrative approach, while its aim is to engage the viewer in a performative way, yet it does not abandon the display of objects and, like the legislating museum, it constructs its message by assigning a meaning to objects and by using their power to amplify its narrative. At the same time, it tells a story with an educational message. As the creator of the museum, Rev. Zygmunt Malacki, emphasised:

There [was] really no developed concept of this type of exhibition in Poland that we could draw on. We didn’t want the Blessed Jerzy Popiełuszko Museum to be a hall of memory. Nor did we reconstruct the interior of his apartment, a monk’s cell or a hermitage, like in Niepokalanów[9] or Kalatówki.[10] It seems that there are few museums in Europe that embody the search for a new vision of a religious exhibition.[11]

As the reverend’s words indicate, from the very beginning the founders wanted to create a new type of museum that offered not only a historic, but also a religious experience, and this not only to a narrow group of believers, but also to a broader audience. For as Rev. Malacki stresses, the exhibition was created for pilgrims, tourists, passers-by, and even atheists and agnostics. The creators wanted to find a means of expression that would appeal to each group while allowing visitors to reflect on contemporary society. As one of the founders said,

our civilisation tells us that what matters most is survival, but we’ve forgotten that not so long ago people believed that honour and being true to one’s principles were more important than survival. This is the story of an ordinary priest, painfully ordinary, who found his mission, his vocation. It seemed to us that the figure of Father Jerzy was very pertinent today. We wanted to dissociate him – I openly admit – from the legend of the ‘Solidarity chaplain’.[12]

That is why “[t]here are many signs at the museum which are essentially questions addressed to each of us, questions about our lives, questions about final matters – about life and death, God, truth, history, responsibility.”[13] The aim of the founders was therefore to create a historical exhibition that would make the viewer inquire into the meaning of his or her own life. It is true that the exhibition is suffused with Christian content, yet the questions it asks are universal.

The museum was opened and blessed on 16 October 2004, in the presence of the late president Lech Kaczyński and Popiełuszko’s mother, Marianna Popiełuszko. The idea was originally conceived by Rev. Teofil Bogucki, but after his death it was realised by Rev. Zygmunt Malacki. The latter formed a team of more than 10 collaborators (including sculptors, painters, graphic artists and architects), and tasked them with the creation of a modern exhibition that would appeal to young viewers. Rev. Malacki defined the purpose of the Blessed Jerzy Popiełuszko Museum as follows:

We would like to see every visitor step out of the role people assume in a typical museum and cease to look at objects and documents from a distance. This museum is supposed to engage each person as a whole, their minds, imagination, emotions, and will. [14]

The creators wanted visitors to open up to the story and not to remain indifferent to what they saw inside. Rev. Malacki implied that visitors to other museums did not become fully involved in the message. Moreover, the intention was for the museum not only to “present facts but also [to] encourage thought and deep reflection on the meaning of life, on man’s place in society, on our responsibility for history, on the mystery of death and sainthood. The museum is not only a place of commemoration but, above all, a place that bears witness.”[15] Therefore, it is a type of sanctuary in the religious sense of the word. This intent is noticeable right at the entrance to the exhibition.

The museum tells the story of the life and martyr’s death of Father Popiełuszko. The first thing that visitors see upon entering the museum is a portrait of Rev. Jerzy Popiełuszko and an inscription which serves as the motto of the exhibition: “The cross became a gate to us”. This is a quotation from a poem by the Polish Romantic poet Cyprian Kamil Norwid, which is supposed to convey the spirit of the times in which Father Popiełuszko lived. However, it is not clear whom the words “to us” refer to. When analysing this exhibition, Karolina Obrębska asked whether they referred to those living under communism or to those entering the museum.[16] The tour guide and other respondents interviewed at the museum stressed that the museum addressed all, regardless of religiosity or religion, and that it was not limited to any specific target group. Thus, on the one hand, the museum is open to the Other, but at the same time, the cross-shaped entrance clearly shows that the curators expect the viewer to be open to the religious message of the narrative.

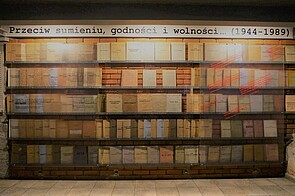

To understand this meaning, the visitor has to walk through nine rooms presenting different stages of Father Popiełuszko’s life. As the founder of the museum explains, the first room, “In the shadow of the PRL [the People’s Republic of Poland, i.e. communist Poland]” was “supposed to show the historical context, that is the totalitarian world, the struggle of good against evil, i.e. of the totalitarian world against the world of God”.[17] This struggle is portrayed through the spatial segregation of the two worlds; on the left, inside display cabinets, are files that were kept by the secret service on priests ministering under communism, to show that “‘the authorities treated each person as a file’ [...].”[18] On the right, the viewer is presented with photographs and testimonies from the period of the Millennium of the Baptism of Poland in 1966, showing society’s immense involvement in Church activities during this time. The whole is completed by a timeline of the most important events in the history of Poland, from 1944 to 1989, which, in the context of this room, is supposed to demonstrate that during the communist period, “the Poles, supported by the Church, struggled against the totalitarian state to defend their faith, freedom, dignity, and nation.”[19]

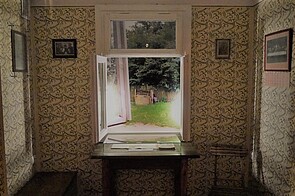

The next room, “Roots”, presents little Alek’s (Popiełuszko’s) childhood in the village of Okopy in Podlasie in the northeast of Poland. The visitor enters this room through the original door brought from Popiełuszko’s house. Inside, they can see little Alek’s authentic cradle, while a photograph of the local landscape has been placed in the window. The room is a reconstruction of Alek’s house. As the creators of the museum explain, “[t]o understand a man, one must go to his family home, look through the window, look at the landscape, walk down the road he walked every day to school, and pray in his parish church”.[20] Therefore, it is not a reconstruction pure and simple; the room carries the profoundly Christian message that one is not born a saint but becomes one.[21] This idea is further developed in the next room, “The soldier’s rosary”, describing the obligatory military service of the young cleric Alek Popiełuszko in Bartoszyce. Among the things we find here is an application letter from the young Popiełuszko to the Catholic Seminary in Warsaw, in which he writes, “I would very much like to practice this profession.” As the creators explain, the letter shows that “every profession is a vocation and should be performed as best as one can.”[22] Both rooms not only present Popiełuszko’s childhood and youth, but also show his maturation into sainthood, and to a large extent are meant to convince the visitor to take the same path.

The next room, “The gift of priesthood”, is one of the largest in the museum. The visitor can circulate around it freely, getting to know different aspects of Popiełuszko’s life and pastoral work. There is a little corner with a desk and the priest’s personal items, as well as the liturgical objects he used. We can listen to sermons he delivered during services for the fatherland at the St. Stanislaus Kostka Church in Warsaw. From this room, the visitor enters a narrow corridor, “The sky has fallen on our heads”, devoted to the introduction of martial law in Poland in 1981. On the wall on the left is a timeline of the events, photographs, and documents issued by the authorities, while on the right we find little crosses, each signed with a name and last name, commemorating the victims of martial law. These lead us to the next room, “Golgotha”.

The murmur of running water, a glowing cross, and photographs of the priest’s battered body remind visitors of the tragedy which took place at the dam in Włocławek. Explaining the decision to feature photographs of the priest’s mangled body taken in the forensics lab, the founder of the museum says: “These pictures are surely brutal, but [...] these austere surroundings are supposed to speak the truth”.[23] Therefore, the photos are not treated as a document of the past, but, instead, play the role of relics of the deceased and are considered testimony, in the religious rather than the historical sense. From the observations of one of the guides, we know that visitors come to pray at “the place symbolising the dam. It is a place that means a lot to them. I can see it, because they are often kneeling there”.[24]

One can hardly imagine similar photographs being presented in a secular exhibition. Historical museums have gradually been abandoning the idea of shocking visitors with images of atrocities, bodies distorted in pain and exhaustion, or corpses, the rationale being not to victimize the victims any further.[25] Contemporary Holocaust museums and exhibitions do not show dead bodies of victims but, instead, present photos of the victims when they were still alive. Witnesses are given a voice through oral history, and a sense of loss is built via lighting, sound, and space. These new forms of presentation, such as representing a void through the use of a narrow corridor or a shaft-shaped space, leading visitors to a darkened room, etc., draw on psychoanalysis, since according to Holocaust scholars (Dominick LaCapra, Frank Ankersmit or Ernst van Akphen), only psychoanalysis can ensure the critical re-working of memory and offer a better understanding of the post-traumatic culture which, as they claim, we live in. As LaCapra writes, we must be aware of the insufficiency of conventional forms of presentation and seek new ways of representing loss.[26]

However, the Blessed Jerzy Popiełuszko Museum does not shun literalness or shocking images of the priest’s battered body, since it positions its message within a different paradigm and takes a different attitude to the visitor. The visit is not only about exploring history, but also serves as a kind of spiritual retreat, supported by the arrangement of the exhibition space. The entrance and exit are located at different ends since, as the architect explained, “the message is clear: we enter a cross and leave, but we do not abandon the cross; instead, we leave the exhibition with the message: ‘vanquish evil with good’[27]. In other words, visitors enter the museum through a cross, they walk through the museum and leave it with a new experience. In this way, the creators of the museum do not only suggest but actually impose the view that the path through life, with a cross as its attribute, is the correct one and one should never stray from it. This moral teaching, explicitly built into the message of the exhibition, is clearly expressed in three last rooms: “A good shepherd has departed”, showcasing the events after Popiełuszko’s death – the prayers in front of the church before his fate was known, and photographs from the funeral, attended by some 800,000 people; “Multiplying the good”, which presents figures of those who “give testimony about the experience of having been fortified with Divine grace, or of having experienced relief from spiritual or physical suffering”; and “Christianity leads to Resurrection”. This final room presents “the victory of good over evil and of life over death”,[28] but also highlights the meaning and purpose of the whole museum. The words of Archbishop Amato, from a homily he delivered during Popiełuszko’s Beatification Mass on 6 June 2010 in Warsaw, are cited here:

I had the opportunity to visit the Warsaw museum devoted to our Blessed martyr, Rev. Jerzy Popiełuszko, on several occasions. Every time, I was moved to tears. The terribly disfigured face of this gentle priest was like the flagellated and humbled face of the crucified Christ, which had lost its beauty and dignity. The bloodied lips of this martyred face seemed to be repeating the words of the Lord’s Servant ‘I offered my back to those who beat me, my cheeks to those who pulled out my beard; I did not hide my face from mocking and spitting (Is 50:6)’.[29]

It is with this deeply religious message that the viewer leaves the exhibition.

As Roman Ingarden writes, “[w]ithout direct and intuitive communion with values, without the joy this communion gives him, man is deeply unhappy. [...]. He feels happy when he can consciously appreciate the existence of values that he himself has created.”[30] Scholars of the condition of modern Western man write that he no longer comprehends the values of his ancestors, he has lost a sense of connection to the past; he is therefore unable to gauge what he will need to build his future identity. This is why he desperately musealises the past, so as not to lose anything important.[31] The historical museums created as a result of this process do of course refer to past events, which gives them a certain power, but they do not relate to lived everyday experience. It sometimes happens that they simulate it.[32] In the case of the Blessed Jerzy Popiełuszko Museum, this condition is reversed. It is first and foremost geared towards preserving the fabric of the past.

Marita Sturkin claims that people are not looking for an original experience, but for an experience that will place them within the continuum of culture. [33] Casey adds that

the tactics of the performing museums are particularly effective […] because of the audience’s interest in a shared sense of cultural history. In the museums the strength of this collective interest in maintaining a specific version of the past allows visitors to suspend disbelief as they explore historical re-creations.[34]

The Blessed Jerzy Popiełuszko Museum draws on universal values: dignity, freedom, truth, and love of one’s fellow man, which underlie not only Christian doctrine but all of European civilisation. This is why the museum is not controversial and is easily decipherable to all viewers, even those who declare themselves atheists. At the same time, the museum strives to conserve the past in the present, to keep it from becoming merely the past. This continuity is supposed to be made possible by religious practice. In the final room, there is a pew which for a long time stood next to Rev. Popiełuszko’s tomb. Today, in the museum, any visitor can use it to pray or simply to meditate on the past. Brochures with prayers to the martyr and holy pictures available at the exit serve a similar purpose. These religious practices are meant to fortify the visitor and make the message of the museum relevant to the visitor’s everyday life. The Popiełuszko Museum is a living space where the past is recalled in a spontaneous way. It is a site that guarantees “the transmission and preservation of collectively remembered values.”[35] The stress on “transmission of values” and not on “preservation of the past” is key to understanding the role of the Blessed Jerzy Popiełuszko Museum.

Zuzanna Bogumił: The Blessed Jerzy Popiełuszko Museum in Warsaw: Between History and Religion. In: Cultures of History Forum (12.01.2018), DOI: 10.25626/0089.

Copyright (c) 2018 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

The official website of the Blessed Jerzy Popiełuszko Museum in Warsaw

Lidia Zessin-Jurek · 20.04.2023

A History that Connects and Divides: Ukrainian Refugees and Poland in the Face of Russia’s War

Read more

Lidia Zessin-Jurek · 20.12.2021

Trapped in No Man’s Land: Comparing Refugee Crises in the Past and Present

Read more

Interview · 08.03.2021

A Ruling Against Survivors – Aleksandra Gliszczyńska-Grabias about the Trial of Two Polish Holocaust...

Read more

Lidia Zessin-Jurek · 03.09.2019

Hide and Seek with History – Holocaust Teaching at Polish Schools

Read more

Maciej Czerwiński · 11.04.2019

Architecture in the Service of the Nation: The Exhibition ‘Architecture of Independence in Central E...

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).