28. Sep 2018 - DOI 10.25626/0090

Maria Kobielska is Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Polish Studies of the Jagiellonian University in Kraków and a member of the Research Center for Memory Cultures of the JU since 2014. Her research interests include contemporary Polish literature and culture with an emphasis on memory, past and politics. Her most recent book discusses Polish memory culture in the 21st century and she is working on a project that focuses specifically on new Polish historical museums.

On 9 March of this year, the Museum of the History of Polish Jews (POLIN) in Warsaw opened its latest temporary exhibition Estranged. March ’68 and its Aftermath (Obcy w domu. Wokół Marca ‘68).[1] During the few months that have elapsed since then, the exhibition has attracted a record number of visitors and has also come in for criticism from various quarters and even crude attacks.[2] It seems that both the format of the exhibition and its public reception give insight into Poland's culture of remembrance in the twenty-first century and especially the mechanisms underlying the particularly sensitive subject to the country's Jewish-Polish past.

The exhibition begins with the most general context: the first display panels remind us of popular perceptions of the 1960s zeitgeist when, to paraphrase Bob Dylan, “the times they were a-changin”. Memories of global counter-cultural movements and social and political change are contrasted, however, with the rather harsh image of life in the People’s Republic of Poland at that time. It is within this reality that the main narrative of the exhibition is set, its key protagonists being Polish Jews or, perhaps more accurately, Jewish Poles[3], of whom there were only around 20 000 living in the People’s Republic twenty years after the tragedy of the Holocaust and the Second World War and following successive waves of emigration.

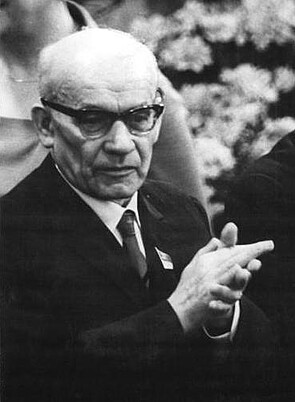

It was primarily their lives that would soon be affected by the political unrest taking place in the People's Republic: fractional infighting within the authoritarian Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR) and anti-Israeli propaganda after the outbreak of the Six-Day War in 1967, when Poland, like other Soviet bloc countries, broke off political relations with Israel. In a notorious speech on 19 June 1967, Władysław Gomułka, the head of state and First Secretary of the Central Committee of the PZPR, accused Jewish Poles of enthusiastically supporting Israeli policies and declared, in no uncertain terms, that there should be no place in Poland for people who displayed such sympathies. Gomułka’s words are quoted in the exhibition narrative to good effect: “We have not prevented Polish citizens of Jewish nationality from moving to Israel if they so wish. We are of the opinion that every citizen of Poland should have only one homeland – the People's Republic of Poland”.

The tense atmosphere in the country would be heightened at the end of 1967, when a theatre play directed by Kazimierz Dejmek, based on Adam Mickiewicz’s Forefathers' Eve (‘Dziady’), one of the most important works of Polish Romanticism, was deemed anti-Soviet and removed from the playbill. The last performance took place on 30 January 1968, triggering protests, notably student demonstrations, which then spread to many towns and cities in Poland. The protests inspired further strikes and demonstrations demanding the democratisation of public life, which later came to be known as the ‘student protests of March 1968’. However, the unrest was quickly suppressed, and in the ensuing propaganda campaign against the protestors, anti-Semitic arguments were once again used. After watching an excerpt from Dejmek’s play – a symbol of freedom and resistance – visitors are presented with a video recording of Gomułka's next anti-Semitic speech, from 19 March 1968, which dominates this section of the exhibition. The audience at the communist party meeting applauded Gomułka enthusiastically, demanding that he adopt an even more belligerent tone. The hate campaign spread throughout the press and took hold of public life in the People’s Republic.

Further on, the exhibition documents the events that took place in March and in the subsequent months of 1968, such as the purge in the communist party and other institutions, the repression suffered by the protesters and specifically by Jewish Poles, and reveals the more general mechanisms of propaganda. The exhibition narrative, which has so far largely focussed on describing the main political events, now turns to the fate of individuals: Jewish Poles forced to leave the country as a result of purges, harassment and hate campaigns, taking difficult decisions, struggling with the consequences of those decisions and, above all, experiencing a devastating sense of grievance and alienation. Around 13 000 people left Poland, their citizenship being revoked. The story of their departure is presented in fascinating and moving detail. For instance, the video shot by the Security Service of the writer Stanisław Wygodzki leaving the country, which even traces his movements at the Warsaw railway station from which he departed, performs the opposite function fifty years on: created as an element of Wygodzki’s harassment, it is now a shocking document of it.

Thus, after 1968, the life of Poland’s Jewish community began to vanish: only a few thousand people remained in the country. Those who left had to face the many difficulties and challenges of exile and emigration; the subsequent exhibition narrative shows the paths they took. The dominant feature of the exhibition, however, is that which is situated between these two histories in the middle of the exhibition space.

Arranged in that space is a symbolic waiting room of the Warszawa Gdańska railway station – the Warsaw station from which most began their journey into exile. The reference is bolstered by a fragment of the original neon sign, placed opposite the entrance to the ‘waiting room’, containing the first letters of the station’s name: WAR, of which only two are still illuminated. This solution makes the visitor think about decline, end and disappearance, about the way in which the burgeoning life stories of specific people were brutally cut short – just as the word ‘WARSZAWA’ is truncated – and about the reality of the shortage economy and how people coped with it as best they could. It is also impossible not to read this inscription as a word in itself – ‘WAR’, a reference to the Second World War and its long shadow; a civil war in which citizens were pitted against each other; and finally the war over memory.

These associations persist as visitors discover in the exhibition space the testimonies of various people affected by the events of 1968. In the glass space of the ‘waiting room’ one can read eighteen separate stories and listen to fragments of interviews in which the protagonists recall their experiences of March 1968. These stories turn out to be very different: sometimes they conform to well-established narratives, but sometimes they offer a surprising and very individual perspective, once again encouraging the visitor to feel empathy and to focus on someone else’s experience.

Opposite the ‘railway station’ is another important element of the exhibition: a large projection screen on which a memorable scene from the film Salto (1965) by Tadeusz Konwicki is displayed. In a space reminiscent of a former synagogue, a bizarre and robotic dance takes place accompanied by disturbing music; the people move as if mechanically or involuntarily performing parallel movements. Justyna Koszarska-Szulc and Natalia Romik, the curators of the exhibition, interpret the scene as “a universal reference to passivity in the face of exclusion, which also happened during the March ’68 events”.[4] It can also be interpreted as a metaphor for the passive repetition of patterns of thinking that are preserved in tradition and memory, which return time and again – also in social and political life. On this reading, the scene is a commentary both on March 1968 and on the Estranged exhibition and the reaction to it in Poland in 2018. The final display boards, which are discussed below, refer to the memory of March 1968 and to the persistence of the mechanisms that gave rise to it. They show that the rhetoric of hatred which framed March 1968 does not belong to the past; that it can be aimed at different targets, and that its modern manifestations are sometimes even strikingly similar to those of half a century ago.

The exhibition is part of a wider Estranged programme, which was inaugurated a year prior to the exhibition’s opening – in March 2017. As the director of the Polin Museum, Dariusz Stola, explains, the aim of the programme is to address the mechanisms of contemporary social memory: the idea is to “evoke the events that took place a half century ago in order to better understand them and to encourage reflection”.[5] In pursuit of this aim, a wide range of activities and media has been used – from the holding of various public meetings, debates and lectures, through educational activities, walks and film screenings, to a theatre competition and performances in the exhibition space itself, which, on the occasion of World Refugee Day for instance, was enriched with the stories of refugees living in Warsaw today.

The curators of the exhibition also emphasise the work being done on contemporary memory and attitudes towards exclusion. The building of solidarity among people serves as a starting point for a universal observation on the uncertainty and instability of life circumstances, which can suddenly change without an individual’s consent and against their will. That is why, according to the authors of the main exhibition catalogue, Estranged is “an exhibition [that] deals with the universal fear connected to losing the sense of security”[6] and, at the same time, one that encapsulates this fear in an historical event and in the experience of 13 000 Polish Jews “expelled from their homeland”, thrown out of their home. The exhibition was thus guided by certain persuasive intent, which was to oppose a nationalist Polish narrative based on myth. In the authors’ opinion, Polish society currently harbours a kind of false consciousness based on the myth of “its righteousness and heroism, secure on the basis of defiance in the face of the oppressive power apparatus”.[7] This is the version of memory which the exhibition tackles and which it aims to transform: to render it more complex and critical and open it up to a multiplicity of individual stories.

The above diagnosis of a kind of false or mythologised memory of March 1968 is instructively developed by Katarzyna Chmielewska in her text 'Two memories', published in the Estranged catalogue. Summarising the observations made so far, she claims that the memory of 1968 in Poland “splits into two separate albeit interacting stories: a heroic narrative of revolt and insurgency (a new beginning for tainted victims of Communism) and a tragic tale of exodus and exclusion (an irrevocable ending)”.[8] The heroic narrative of protest, however, being part of the history of society’s resistance to communism, takes centre stage vis-à-vis the tragic story of the expulsion of Jewish Poles. The latter plays a somewhat auxiliary role in the culture of remembrance: it serves “as an example of the system’s repressions that impacted fellow citizens.”[9] The only perpetrator of this oppression turns out to be the communist authorities – by implication foreign and imposed from outside; the ‘real Poland’, Polish society, remains innocent. Although this image is contrary to documentary evidence and testimonies revealing widespread cases of persecution and support for exclusion, and the persistence of anti-Semitic codes in society, the mythical story eclipses the real one. This framing has proved to be persistent and defines the framework within which the exhibition operates, its impact, and the reactions it has elicited.

The very title of the exhibition has proved controversial. A literal translation of Obcy w domu would be ‘alien/foreign in [one's own] home’; just as the term ‘estranged’, emphasising the exclusion faced by Jewish Poles, it does not fit easily into the framing of March 1968 mentioned above. Even Dariusz Stola admits that during the initial phase of discussions about the project he wanted to tone down its message by adding a question mark after the title. Eventually, however, as he has explained in an interview, he became convinced of the existing wording, which simultaneously and powerfully emphasises the

mechanisms by which the authorities operated, […] the nature of the campaign conducted by the communist authorities, whose aim was to convince Poles that Polish Jews were not like them, that they were alien and had no right to call Poland their homeland,

and the effect of these actions – that the citizens affected by them did indeed feel estranged, unwanted, and cast out of what used to be their common home.[10] Those who criticised the title concurred with only the first of these observations – they assumed that calling the exhibition Estranged was tantamount to accepting the point of view of the communist authorities, which at the time nobody in Poland shared. Jarosław Sellin, Deputy Minister of Culture and National Heritage, described the title as “quite controversial” in a TV programme, because “if anyone treated Jews in 1960s Poland as ‘foreign’, it was the communists”.[11]

This simple, journalistic critique of the title of the exhibition can be expanded upon in reference to Bronisław Świderski’s long text published in 2017 in Kronos, a conservative philosophical and literary quarterly.[12] Świderski, a writer and translator, was a participant of the March 1968 events and has been living in exile in Denmark ever since. He recounts his experience, pointing to the feeling of unity he felt with others who were protesting against the authorities, i.e. the opposite of alienation, as the cornerstone of that experience. He sees his attitude, both in Poland and later in exile, as a “continuation of the struggle pursued by Poles against ‘rulers’ imposed by the Russians, and not as the gesture of an ‘alien’.” In Świderski’s opinion, the controversial phrase repeats Gomułka’s anti-Semitic rhetoric – seemingly endorsing the First Secretary’s view that there were indeed certain ‘alien elements’ in Poland at that time – and, worse still, uses the mechanism of victimisation, turning all Polish Jews into a homogeneous group, i.e. victims. Świderski’s axiological and ideological argumentation is rooted in anti-communism (as evidenced by the other topics that permeate his article: political vetting and the settling of accounts with Jewish and non-Jewish Poles who allegedly collaborated with the communist authorities), which makes his account all the more interesting as it adds to the diversity of views held by the participants of the 1968 events; it can also be seen as a good example of how the mechanisms of memory work.

These mechanisms are also visible in the statements of the Polish Prime Minister, Mateusz Morawiecki. In a speech during the commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of March 1968, Morawiecki referred polemically to the title of the exhibition, claiming that Jewish Poles were never alien: “They were in their home, they were their own people, our citizens.” The purpose of such polemics is, of course, to deny the approval with which society greeted anti-Semitic rhetoric at the time and to hold the communist authorities solely responsible for the March events – in the service of a purely self-affirming vision of Poland’s past. Given that assumption, the Prime Minister was able to say – although it sounds incredibly audacious – that March 1968 “should be [for Poles nowadays] a source of pride”, because it was national revolt against the oppressor, and real Poles had nothing to do with the persecution of Jews.[13]

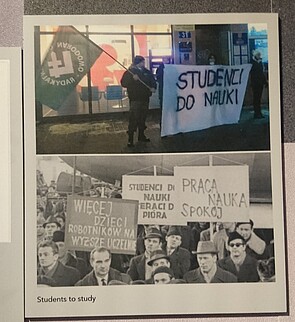

The pretext for the biggest controversy was the final section of the exhibition, mentioned earlier. This section juxtaposes contemporary media images and texts that use the mechanisms of exclusion with their precursors from March 1968. Thus, for example, a radio comment by a right-wing journalist, Piotr Nisztor, in January 2018 during the dispute over the recent amendment to the IPN law (the so-called ‘Holocaust Law’) reverberates with Gomułka’s words from June 1967: “If today someone is acting as a spokesman for Israel, then perhaps he should simply consider once again whether to exchange his Polish citizenship for Israeli citizenship”. Another example shows an anti-government demonstration in 2017 organised by students from the city of Opole meeting a counter-demonstration organised by members of the National Radical Camp, an extreme right-wing, neo-Nazi grouping, who hold a banner with the slogan “Students get back to your studies”. The photograph is juxtaposed here with a poster bearing exactly the same slogan, which was used in 1968 during counter-demonstrations inspired by the authorities that were designed to express condemnation for the March student strikes (see picture). Headlines referring to the “Polish Witch-Hunt” or the “Anti-Polish Campaign” being conducted abroad, although created fifty years apart, are also strikingly similar. This section of the exhibition closes with an interactive ‘Hate Monitor’ – a database where visitors can browse an archive of hate speech in the public domain compiled by the HejtStop organisation as well as bile-filled correspondence received by various institutions such as the Israeli Embassy.

The quotations are anonymised, even if their authors are public figures – only the medium in which the statements appeared is indicated. As explained on the display board, the aim was to reveal the “mechanisms behind the rhetoric of hatred, triggered by communist propaganda campaigns such as the one in March 1968”, which “have remained in the language, especially where reference is made nowadays to refugees, political opponents, Germans, homosexuals, and Jews”, and not to stigmatise specific people. Two journalists, however, recognised their own statements and expressed their indignation, giving the matter huge publicity.

The first of those journalists was Magdalena Ogórek, a public figure with a complicated ideological biography: in the 2015 presidential election she gained recognition as the candidate of the Democratic Left Alliance, but then she went on to become a journalist for... the conservative media, including public television, which is dominated by the governing right-wing party. The exhibition features a tweet by Ogórek in which she asks the left-wing senator Marek Borowski about his alleged “change of surname from Berman to Borowski”. This is juxtaposed with a fragment of a 1968 press article whose author ‘unmasks’ a famous writer, exposing his ‘real’ surname that suggests Jewish origin. Ogórek demanded an apology, claiming that her statement had no anti-Semitic context; rather, it was “anti-Stalinist” because it had sought to investigate whether Borowski was related to the Berman family of communist activists. As Dariusz Stola commented, the tone of her statement clearly referred to the origin and identity of the senator: “Arguing that there is something suspicious about this, about someone changing their name to a Polish-sounding one, amounts to denying Mr Borowski the right to be a Pole like any other"[14] and thus repeats the act of exclusion, which is what the whole exhibition is about. Undeterred, Ogórek sued the director of the Polin Museum for defamation; the case is still awaiting resolution.

A similar case, brought by the right-wing journalist Rafał Ziemkiewicz, is also about to go through the courts. His tweet from January 2018, which refers to the aforementioned dispute over historical policy, is one of the exhibits in the contemporary section of the exhibition. In it, Ziemkiewicz declares that for years he has supported Israel through his journalism, but now, in the present dispute, he “feels like a fool” - due, as he puts it, to the actions of “a couple of stupid or greedy scabs” on the Israeli side. This extremely offensive term (parch, meaning ‘scab’ or ‘mange’) derives from pre-war anti-Semitic propaganda, which associated Jews with biological danger, disease, and repulsiveness. Referring to the inclusion of his tweet in the exhibition, Ziemkiewicz attacks the activities of the Polin Museum as such, claiming that its main purpose is to build a false narrative of widespread Polish anti-Semitism.[15] Commentaries on the high-profile cases of Ogórek and Ziemkiewicz have been very common in the Polish media, particularly in the right-wing and nationalist media. What is especially significant, however, is that they have also served as a pretext for politicians to evaluate and pass judgement on the exhibition and the activities of the museum.

It was, again, the last section of the Estranged exhibition and the publicity surrounding it that prompted two senators from the ruling Law and Justice party, Rafał Ślusarz and Artur Warzocha, to address a series of questions to the Minister of Culture and National Heritage, Piotr Gliński, in March 2018. In their letter, made available on Artur Warzocha’s twitter profile, the senators argued that the statements included in the exhibition had been “tendentiously interpreted as examples of anti-Semitic discourse, whereas in fact they are not”, and that the controversy had led to Poland being falsely accused of anti-Semitism in the international arena. Consequently, they wanted to know how the Minister was supervising the Polin Museum and what steps he intended to take to influence the institution’s activities.

In the context of such overt political pressure, the organisational structure of the Polin Museum is important. It is the first museum in Poland to be created in the form of a public-private partnership, organised jointly by central government (the Ministry of Culture), local government (the City of Warsaw), and a non-governmental organisation – the Jewish Historical Institute Association. When the museum came into existence, the Ministry financed the construction of its architecturally impressive building, while the Association raised funds for the creation of an equally spectacular permanent exhibition. As part of its activities, the museum seeks public funding for further projects; the Estranged programme has been supported by private entities, the Jewish Historical Institute, and the City of Warsaw, but it has received no subsidies from the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage. The latter, when answering journalists’ questions on the subject, cited as an argument in favour of withholding subsidies its “disapproval of the unauthorised linking of the events of March 1968 with current phenomena within the framework of the exhibition,”[16] hence, one could add, its disapproval of the way in which the exhibition analyses the longevity of mechanisms of exclusion, non-memory and hate speech.

Due to the complex structure of the Polin Museum, the Minister has no decisive influence over the way it operates. However, the assessment given to the exhibition by people associated with Poland’s ruling party, and the Minister’s other pronouncements, suggest that he would like to have such influence. Even before the Estranged exhibition opened, the new composition of the Museum Council came in for a lot of criticism, precisely because – due to the nature of the agreement between the organisers – Council members associated with the Law and Justice party were in a minority.[17] On the very day the temporary exhibition opened, the Minister announced that a new museum dealing with the subject of Polish-Jewish history would be established in Warsaw: The Museum of the Warsaw Ghetto. As the Minister pointedly explained in an official communiqué, this new museum would be part of the government’s historical policy and would focus on the positive side of Polish-Jewish relations; it would tell – by implication, in contrast to the Polin Museum – the story of the “mutual love that exists between the two nations.” There was speculation that the creation of the new museum could be the first step towards its eventual merger with the Polin Museum, the replacement of the latter’s management and, as a result, the take-over of that institution.[18] This type of interference in the functioning of a cultural institution – similarly to the above-quoted politicians’ comments about its activities – might seem unusual were it not for the fact that a precedent has already been set in Poland: exactly the same fate recently befell the Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk.

The Estranged exhibition has been exceptionally well attended and has received a great deal of media coverage. The controversies surrounding it are bad news so long as they defend hate speech and falsely deny the difficult story told by the exhibition and its even more difficult-to-accept contemporary echoes. Paradoxically, however, they have contributed to the recognition of the project and its resonance – as reported by the media monitoring platform in March, the discussion around the Polin Museum’s activities has greatly increased media interest in the institution.[19] By its closing date (24 September 2018), the Estranged exhibition had been seen by a record-breaking 110 000 visitors.[20] The exhibition has become a litmus test of the culture of remembrance in today’s Poland: whereas the controversies it has caused reveal the persistence of patterns of thinking about the past and the powerful impact of historical policy, the very existence of the exhibition proves that there is also room for comprehensive, critical and responsible action in this area.

Translated by Jasper Tilbury

Maria Kobielska: History and memory of 1968 in Poland: Debates around the 'Estranged '68' exhibition. In: Cultures of History Forum (28.09.2018), DOI: 10.25626/0090

Copyright (c) 2018 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

See the article on the current situation of the POLIN Museum (with reference to the 'Estranged '68' exhibition) by Martha Gessen in The New Yorker (23.09.2019).

Lidia Zessin-Jurek · 20.04.2023

A History that Connects and Divides: Ukrainian Refugees and Poland in the Face of Russia’s War

Read more

Lidia Zessin-Jurek · 20.12.2021

Trapped in No Man’s Land: Comparing Refugee Crises in the Past and Present

Read more

Interview · 08.03.2021

A Ruling Against Survivors – Aleksandra Gliszczyńska-Grabias about the Trial of Two Polish Holocaust...

Read more

Lidia Zessin-Jurek · 03.09.2019

Hide and Seek with History – Holocaust Teaching at Polish Schools

Read more

Maciej Czerwiński · 11.04.2019

Architecture in the Service of the Nation: The Exhibition ‘Architecture of Independence in Central E...

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).