27. Sep 2016 - DOI 10.25626/0053

Ekaterina Makhotina is assistant lecturer at the Department of History of Eastern Europe at the University in Bonn. Her first book deals with memory on Stalinism at the White-Sea Canal (Belomorkanal) “Stolzes Gedenken und traumatisches Erinnern: Gedächtnisorte der Stalinzeit am Weißmeerkanal.” Frankfurt am Main 2013. In January 2015 she obtained her PhD from LMU Munich with a thesis on the development of cultural memory of WWII in Soviet and post-Soviet Lithuania: "Erinnerungen an den Klieg - Krieg der Erinnerungen. Litauen und der Zweite Weltkrieg. Göttingen (forthcoming 2016)".

She coordinated the international project, that investigates the social practices of war remembering on the 9 May in the post-socialist space (together with Mischa Gabowitsch and Cordula Gdaniec): “Victory—Liberation—Occupation: War Memorials and Commemoration marking the 70th Anniversary of WWII Ending in post-Socialist Europe” and the universitary project “Münchner Leerstellen: Forgotten Sites of Memory on the Nazi Violence in Munich. A Virtual Exhibition“.

The topic of complicity in the Holocaust has once again become the subject of heated debate. While the Polish government's move to strip internationally renowned Holocaust researcher Jan Tomasz Gross of his Order of Merit has sparked outrage around the world, Lithuania is having its own Jedwabne-style debate. The book Our People: Journey with an Enemy by Rūta Vanagaitė, which describes the complicity of Lithuanians in Holocaust crimes, is currently the subject of fierce and controversial debate.

The effect the book is having is indeed quite similar to that of Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne by Jan Tomasz Gross, which came out in 2001. To put it bluntly, Vanagaitė's book is about the unfettered violence of Lithuanians against the Jewish community, about how they murdered and plundered their Jewish neighbors, motivated either by everyday anti-Semitism or by the desire to enrich themselves on Jewish property. The novelist and journalist Vanagaitė wants to shed light on the cooperation and complicity of her fellow citizens.

22 June 1941 marked not only the beginning of the German war of extermination against the Soviet Union; it was also the start of the total annihilation of Jews in the Soviet territories occupied by the Germans. Lithuanian Jewry was hit hard by German plans for extermination. It had the largest Jewish minority of the three Baltic republics, with 220 000 Jews, or Litvaks, living there before the war.

In the years of German occupation, 1941–44, about 200 000 Lithuanian Jews became victims of the Nazi extermination policy; only about 4 percent of the Jewish population survived. The majority of Lithuanian Jews, about 137 000, were executed in 1941 during the first five months of the war, as documented by the infamous "Jäger Report", one of the most harrowing testimonies of the Holocaust. For German war planners, the extermination of the Jews in the Baltics was the prelude to the murder of Soviet Jewry, a key component of their blitzkrieg. Lithuania was unique among German-occupied territories. German decision-makers were especially quick and thorough here in their resolution to liquidate the Jews. The persecution of Jews in Lithuania meant stripping them of their rights, arbitrary arrests in broad daylight, ghettoization, mass shootings, and later, once the Jewish ghetto was dissolved, deportation to extermination camps or forced labor in Germany. By the end of the war a mere 8 000 Jews had survived – about 800 of them in Vilnius, once the most important cultural center of Eastern European Jewry, the 'Jerusalem of the North', as the Litvaks lovingly called it. The extent of these crimes and the speed with which they were committed cannot be explained without the willing collaboration of the local population. The genocidal policy of the German occupiers was aided and abetted by locals, whether in the form of failing to come to the aid of the persecuted, the anti-Jewish pogroms unleashed in the first weeks of the war, or serving in the Sonderkommandos, the "special units", and police battalions that the SS Einsatzgruppen readily employed in carrying out their mass executions.

In the first week after the German invasion – German tanks rolled into Vilnius just one day into the invasion, on 23 June 1941 – pogrom-like riots against the Jewish population began. In the literature, the complicity of Lithuanians is almost always viewed in the context of the first year of Soviet rule, 1940–41, which has gone down in the collective memory of Lithuania as the terrible year of 'Russian rule.' The divvying up of Eastern Europe between Stalin and Hitler in the wake of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact marks the start of foreign hegemony in the Lithuanian culture of memory, despite the fact that Soviet powers took Vilnius away from Poland and gave it back to Lithuania. For the Jewish population, the fact that Lithuania was in the Soviet sphere of influence and not under Nazi Germany meant a greater chance of survival. For non-Jewish Lithuanians, the transformation into a Soviet socialist republic represented the loss of national sovereignty, the overwhelmingly positive attitude of their Jewish neighbors towards the Soviet Union being deemed a 'betrayal.' Extreme nationalist and anti-Semitic attitudes proliferated. When Soviet state security began deporting ethnic Lithuanians to Siberia a week before the outbreak of war, many Lithuanians interpreted this move as a targeted campaign of 'Jewish communists' against the Lithuanian people. Following the German invasion of Lithuania – like Estonia and Latvia, the republic was not an independent war aim but a transit area en route to Leningrad – there was a wave of self-proclaimed 'retaliatory' riots against Jewish citizens.

In particular the massacre at the Lietūkis garagein Kaunas on 27 June 1941, where young Lithuanian nationalists savagely murdered 70 to 100 Jewish citizens, has become a symbol in international Holocaust remembrance of the active complicity of Lithuanians. The fact that, from September 1941 on, it was exclusively Lithuanian policemen who drove the Jews into the ghettos, carried out 'raids,' and took part in 'campaigns' against them might explain the central role that Lithuanian perpetrators play in the memories of Jewish survivors. If asked about the perpetrators, survivors nowadays will usually talk about baltraiščiai, the "white-armbanders", meaning the young Lithuanians who participated in the pogroms and wore white armbands as a sign of their anticommunist sentiments. Another word later took root, one that induced fear and terror: šaulysai, the gunmen, referring to the Lithuanian policemen who carried out the mass executions. It shows that being killed by Lithuanian neighbors is a well-established motif among survivors.[1]

Another basic premise of Lithuanian remembrance is that the wave of anti-Jewish violence was due to the Germans being in their country, the occupiers having fomented anti-Semitic (but also anti-Polish and anti-Russian) resentment and documented the pogroms photographically. Finally, the mass participation and brute force evidenced by Lithuanians suggest that they engaged in "unsystematic mass violence" against their Jewish neighbors.[2]

The murder of Jews during the first days of occupation was and is still considered justified by some Lithuanians as acts of retaliation and revenge for the suffering inflicted during the initial "Soviet" years. This notion is also found in the theory of double genocide that emerged in the Baltic exile community and which claimed that the communists (= Bolsheviks) began by persecuting and killing Lithuanians first and only then, "in wrath and fury", did the Lithuanians retaliate against the Jews. The polemic against Vanagaite's book makes reference to Rainiai and Pravieniškes as well, the scenes of crimes committed by the retreating Soviets in 1941.

The debate about the historical responsibility of Lithuanian society is by no means new; it has been a sore spot in Lithuanian-Jewish and Lithuanian-Israeli relations ever since the early 1990s.[3] The director of the Jerusalem office of the Simon Wiesenthal Center, Efraim Zuroff, underscored soon after Lithuanian independence in 1990 that no diplomatic relations could be established between the two states if Lithuania did not take certain steps towards reconciliation with the Jewish community and Israel. This included returning communal property to the Jewish community, officially documenting all places of mass extermination, safeguarding documents that reveal the involvement of local authorities and making sure these documents can be accessed at all times for research purposes, as well as helping locate and extradite Lithuanian co-perpetrators from America and Canada. Zuroff had expressed repeated doubts about the sincerity of the Lithuanian government's efforts to come to terms with the past. A number of protracted court proceedings against Lithuanian co-perpetrators, the most famous of which was probably the case of Aleksandras Lileikis, prompted him to publicly admonish Lithuania as a "paradise for war criminals". Efraim Zuroff has thus long been perceived as an enemy by the Lithuanian national conservatives, and the fact that Vanagaitė prepared her book with him of all people has brought her accusations of "treason". In the summer of 2015, the Lithuanian journalist traveled with Zuroff, the Israeli historian with Litvak roots, to the sites of Jewish extermination in Lithuania. There are about 200 of these in Lithuania – a sad peculiarity on the European Holocaust map. Her conversations with Efraim Zuroff, the "enemy" in the title of her book, make up a significant part of the volume. For him it was a journey to the final resting place of family members, for her an attempt to come to terms with her people's past – some of her own ancestors included, whom she suspects of being complicit in crimes against the Jews.

There wasn't always the need for a 'troublemaker' from outside, however, to trigger public debate about the country's own perpetrators and victimized 'others.' A 1995 speech by Lithuanian president Algirdas Brazauskas in the Knesset, in which he asked for forgiveness for the misdeeds of his countrymen during the war, unleashed a wave of indignation back home. The so-called "primary guilt" of the Jews was invoked as an argument and apology – a motif of remembrance that had already circulated in exile in the form of the abovementioned theory of double genocide.[4]

The two "genocides" do in fact coexist in public debate in Lithuania.[5] According to a law passed in April 1991, the crimes of the Nazi and Soviet occupation forces are both classified as "genocide against the citizens of Lithuania". Lithuanians who suffered under the Soviets in 1940–41 and 1944–90, especially those who were deported to Siberian camps, are commemorated as victims of genocide. The use of the term genocide to define Soviet practices of persecution happened here well before the Holodomor was encoded in Ukrainian law (2006) and recognized in many states throughout the world as a genocidal crime, thus establishing the term genocide in Western research on Stalinism.[6] Since 2010 genocide denial, whether "Soviet genocide" or the Holocaust, has been classified as a crime in Lithuania, punishable by up to two years in prison.

The juxtaposition of these two historical events makes the coexistence of remembrance cultures inherently problematic. In the country's national culture of remembrance, Soviet genocide takes top priority. Indeed, the Museum of Genocide Victims, devoted to Lithuanian suffering and Soviet perpetrators, is the most important and elaborate educational institution in the country. The Genocide and Resistance Research Center, established already in 1992 as an outgrowth of the commission responsible for researching Bolshevist crimes, is the central institution of historical policy in Lithuania. According to its statute, it researches Nazi as well as Soviet crimes, but a cursory glance at its activities and publications reveals that its focus is clearly on the Soviet period.

Yet just like the crimes of Stalinism, the history of violence against Lithuanian Jews (and other victims of German occupation) had hardly been investigated at the time of the institution's founding. During the Soviet era the Jews were not presented as the primary target of the German policy of extermination but as merely one group of victims among others. The occasional Jewish survivor returning to the homeland, to Vilnius, from American or Israeli emigration barely recognized their city anymore. No longer the Jewish place they remembered, it had morphed into something Soviet, Lithuanian, socialist-monumental. They were shocked that the Jewish cemeteries were gone, and that the memorial site of Paneriai referred to undefined "Soviet citizens" having been the victims of German aggression (between 1941 and 1944 about 100 000 people were murdered there, about 70 000 of whom were Jewish). Thus, the difficulties of addressing Jewish suffering must be seen as a deficit of Soviet historiography, which made no explicit reference to the Jewish identity of victims nor to the violence committed by their Lithuanian neighbors.

This refusal during the Soviet era to address Jewish victims as Jewish shifted the memories of Paneriai to the sphere of the family and the diaspora. But the Jewish community of Lithuania reconstituted itself under perestroika and vehemently demanded its right to remembrance during the 1990s. One of its first activities was the erection of a Jewish memorial stone in Paneriai and commemorative ceremonies for Jewish victims. The first exhibit took place in 1991 at the Green House branch of the Jewish State Museum in Vilnius, "the first institution to speak and to teach about the Holocaust", according to its long-time director Rachel Kostanian. Even before the topic became the subject of scholarly research – the first works by professional historians were published in the late 1990s – Jewish survivors had been giving talks at the Green House about their suffering, losses, and fighting in the resistance.

The museum-makers at the Green House have likewise addressed an "unpleasant" chapter of shared Lithuanian-Jewish history: Lithuanian complicity in the Holocaust. The exhibit includes a documentary film by Saulius Berzinis entitled "The Lovely Faces of the Murderers", showing interviews with aged Lithuanian policemen who took part in the shootings. A key image of Lithuanian perpetrators – a photo of the Lietūkis massacre – occupies an important place here.

The question remains as to what extent this effort to work through the past will reach the Lithuanian public. The elaborately designed Tolerance Center, a new branch of the State Jewish Museum dealing with the cultural history of Jews in Lithuania, has received much more attention than the Holocaust exhibit.

A glance at the financial endowment and facilities of the Green House Holocaust exhibit and the Museum for Genocide Victims as well as at their tourist ranking makes abundantly clear that the current politics of history in Lithuania accord secondary importance to Holocaust victims.

The official line of Lithuanian memory politics is not purely aimed at a history of victimhood. The heroic postwar anti-Soviet resistance against the new authorities occupies an almost sacred place in the national culture of remembrance. The contradictory perceptions of anti-Soviet resistance fighters frequently rekindles the conflict between Jewish and Lithuanian remembrance, the key figures of anti-Soviet resistance being under suspicion of having participated in the mass extermination of Jews during German occupation. In 2009, about 4 000 individuals were identified as "Jew killers" by Joseph A. Melamed of the Association of Lithuanian Jews in Israel, among them the much venerated partisan leaders Adolfas Ramanauskas (Vanagas) and Juozas Lukša.The repatriation of the mortal remains of Juozas Ambrazevičius from the United States to Kaunas in 2012 in a solemn state ceremonywas another source of negative international publicity. In the early phase of Soviet occupation, Ambrazevičius was an outspoken member of the anti-Soviet Lithuanian Activist Front which, under the leadership of Kazys Škirpa and in collaboration with Nazi Germany, endeavored to restore Lithuanian independence. He was prime minister of the Provisional Government of Lithuania for the brief duration of its existence. His government also initiated the first restrictive laws against Jewish citizens, 'legitimizing' their disenfranchisement and ghettoization. This aspect of his career has been successfully overlooked in Lithuania. In 2009, Juozas Ambrazevičius was posthumously awarded the Grand Cross of the Order of the Cross of Vytis, the highest Lithuanian honor. A lecture hall at Vilnius University bears his name, complete with a commemorative plaque and portrait.

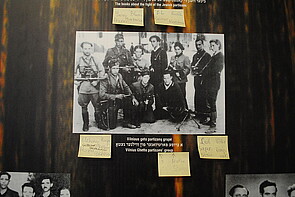

In 2007–08 it became clear that the designations of 'perpetrator' and 'hero' varied considerably depending on the community of memory one belonged to. The Lithuanian Prosecutor General's Office pressed charges against former Jewish resistance fighters in Soviet partisan units, including Fania Brancovski and Rachel Margolis, both long-time activists at the State Jewish Museum (Green House), and Yitzhak Arad,[7] the former director of the Yad Vashem memorial. These individuals were suspected of attacking the village of Kaniukai and accused of committing war crimes.The most scandalous thing about the affair was how long the investigations lasted and the negative coverage in the press about the misdeeds of Soviet partisans. International pressure and the involvement of several Lithuanian historians eventually led to the charges being dropped. In 2009 Fania Brancovski was awarded the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, presented to her by the federal president, for her struggle against Nazism, indicating once again quite clearly the dividing lines between East and West in the European landscape of remembrance.

According to Aleida Assmann, remembrance in dialogue – a model in which the suffering inflicted on one's neighbors is assimilated into one's own national memory – is a future opportunity for European remembrance.A prerequisite to this is overcoming mononational cultures of remembrance aimed at narratives of national victimhood and charged with myths of heroicism. This includes recognition and empathy for the other victims of history and the willingness to critically assess one's own role as a perpetrator. As Peter Esterhazy (1950–2016) once wrote, we need more knowledge "about ourselves – as murderers and victims."

To what extent is Vanagaitė's book a chance for Lithuania to engage in a critical discussion about its own role during German occupation? The book was certainly not ignored, but widely received like no other history book of late. In a matter of days, 2 500 copies were sold and the book was number one on the bestseller list for several weeks straight. Was this motivated by the desire to know if one's own grandfather or great uncle had been mentioned as a Jew-killer in the book? Or was interest piqued by the buzz of critical reviews penned by conservative historians and politicians? The national-conservative historian Nerijus Šepetis, for example, claimed that Our People was devoid of any scholarly merit, and well-known Lithuanian politician Vytautas Landsbergis, the Sąjūdis leader and voice of conservatives, viewed the book as pathos-laden and fictionalized. But it was precisely the book’s straightforward language, its exhilarating journalistic road story of searching, encountering, silence and remorse that made the book a bestseller in the first place and effectively launched a public debate about the complicity of Lithuanians. Lithuanian intellectuals at least see it as an important impetus to promote more research on the topic and more public awareness. There's certainly plenty of potential to do so.

An initial effect is already evident at the level of historical policymaking, the Genocide and Resistance Research Centre having already announced the upcoming publication of a Lithuanian "list of perpetrators".[8] The list includes the names of more than 2 000 individuals suspected of murdering Jews, even though the centre's director is quick to point out that "each individual's guilt could only be decided by the courts". [9] The Jewish community of Lithuania has called on the Lithuanian Prosecutor General's Office to actively investigate the individuals on the list.

There is no denying that the debate around Our People has had some positive effects. One sign of the opening of Lithuania's culture of memory towards Jewish victims was the broad participation at commemorative ceremonies in Molėtai (Malat) on 29 August. About 3 000 individuals, most of them non-Jewish, joined a procession as part of the memorial ceremony for the Jews who were murdered there 75 years ago. They walked the same path that approximately 2 000 Jews of Malat walked in late September 1941 on their final march: they arrived and were shot to death and buried in mass graves. The appeal of one of Lithuania's greatest living authors, Marius Ivaškevičius, who proclaimed to his fellow Lithuanians, "I’m not Jewish", undoubtedly had an enormous impact: "Let’s take that path, it's not easy, but it isn’t impossibly difficult ... We will go visit those who have been waiting for us three-quarters of a century. I believe that as they were dying, they nonetheless knew the day would come when Lithuania would turn back to them. And then they would return to her. Because Lithuania was their home. Their only home, they had no other." Vytautas Landsbergis, too, took part in the procession, a signal to national-conservative forces in Lithuania to be conscious of other victims of twentieth-century history and to commemorate them as well.

Further, this year's unofficial commemorative actions on 23 September, the Day of Commemoration of the Jewish Genocide, was a sign of the slow but serious change in the public's approach towards the memory of our Jewish neighbours: several dozens of Lithuanians participated in Rūta Vanagaitė's initiative "Čia guli musiškiai" (Our People lie buried here) at the town of Vėliučionys, a muss murder site about 12 kilometres away from Vilnius. Vanagaite made an appeal on social media for people to go to the site by car or bus, to walk the last portion of the way, to light a candle and put a stone on the mass grave of the 1 159 Jews killed there on 22 September 1941. This local, bottom-up initiative complemented the official commemoration ritual at Ponar and the official commemorative action "The Way of Memory", during which schoolchildren and teachers visit the memorial sites.[10] Ruta Vanagaite's appeal is not only about the commemoration; rather, it is about the definition of "Musiškiai" – Our People, about the perception and commemoration of Jews as 'Ours' and the integration of Jewish victims in the national memory culture.

These developments, coupled with the desire of many Lithuanians to read this provocative book and come to their own conclusions, will likely do more to increase awareness than any academic discussion ever could.

Translated by David Burnett

Ekaterina Makhotina: We, They and Ours: On the Holocaust Debate in Lithuania. In: Cultures of History Forum (27.09.2016), DOI: 10.25626/0053.

Copyright (c) 2016 by Imre Kertész Kolleg, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the copyright holders. For permission please contact the editors.

The following is an expanded version of “Die Unsrigen: Die Holocaustdebatte in Litauen” by Ekaterina Makhotina, published in German at Erinnerung.hypotheses.org on February 26, 2016.

A critical review of 'Our People' by the Lithuanian lawyer and author Karolis Jovaišas for the news website DELFI

Joint Statement by the Lithuanian Jewish Community and the Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum on the Ceremonies for the Reburial of Juozas Brazaitis (Ambrazevičius).

See the “Münchner Leerstellen” (Munich Blank Spots) project at the University of Munich, tracing the fate of forced labourers in Germany. See for example: Sally Ganor, Abba Naor, and Uri Chanoch, who were deported from Lithuania (Kaunas) to Munich for employment in the German war economy: http://www.muenchner-leerstellen.de/archives/344

The “The Holocaust Atlas of Lithuania” (initiated by the Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum and the Austrian Verein Gedenkdienst) consists of structured and concentrated information on all the mass murder sites in Lithuania.

See a related article by Benas Gerdziunas in Politico (2017)

Violeta Davoliūtė · 30.09.2023

Lithuania’s Postcolonial Iconoclasm – or Politics by Other Means

Read more

Violeta Davoliūtė · 29.09.2021

Trials and Tribulations: The Lithuanian Genocide and Resistance Research Centre Reconsidered

Read more

Violeta Davoliūtė · 19.12.2018

Between the Public and the Personal: A New Stage of Holocaust Memory in Lithuania

Read more

Violeta Davoliūtė · 17.11.2017

Heroes, Villains and Matters of State: The Partisan and Popular Memory in Lithuania

Read more

Rasa Baločkaitė · 12.04.2015

The New Culture Wars in Lithuania: Trouble with Soviet Heritage

Read more

Get this article as PDF download (including pictures).